Landscape Architecture: Landscape Architecture: - School of ...

Landscape Architecture: Landscape Architecture: - School of ...

Landscape Architecture: Landscape Architecture: - School of ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

4<br />

<strong>Landscape</strong><br />

<strong>Architecture</strong>:<br />

Site/Non-Site<br />

Guest-edited by Michael Spens

4Architectural Design<br />

Backlist Titles<br />

Volume 75 No. 5<br />

ISBN 0470014679<br />

Volume 75 No. 6<br />

ISBN 0470024186<br />

Volume 76 No. 1<br />

ISBN 047001623X<br />

Volume 76 No. 2<br />

ISBN 0470015292<br />

Volume 76 No. 3<br />

ISBN 0470018399<br />

Volume 76 No. 4<br />

ISBN 0470025859<br />

Volume 76 No. 5<br />

ISBN 0470026529<br />

Volume 76 No. 6<br />

ISBN 0470026340<br />

Volume 77 No. 1<br />

ISBN 0470029684<br />

Individual backlist issues <strong>of</strong> 4 are available for purchase<br />

at £22.99. To order and subscribe for 2007 see page 144.

4Architectural Design<br />

Forthcoming Titles 2007<br />

May/June 2007, Pr<strong>of</strong>ile No 187<br />

Italy: A New Architectural <strong>Landscape</strong><br />

Guest-edited by Luigi Prestinenza Puglisi<br />

Every five or six years, a different country takes the architectural lead in Europe: England came to the<br />

fore with High Tech in the early 1980s; by the end <strong>of</strong> the 1980s France came to prominence with<br />

François Mitterrand’s great Parisian projects; in the 1990s Spain and Portugal were discovering a new<br />

tradition; and recently the focus has been on the Netherlands. In this ever-shifting European landscape,<br />

Italy is now set to challenge the status quo. Already home to some <strong>of</strong> the world’s most renowned architects<br />

– Renzo Piano, Massimiliano Fuksas and Antonio Citterio – it also has many talented architects like<br />

Mario Cucinella, Italo Rota, Stefano Boeri, the ABDR group and Maria Giuseppina Grasso Cannizzo, who<br />

are now gaining international attention. Moreover, there is an extraordinary emergence <strong>of</strong> younger<br />

architects – the Erasmus generation – who are beginning to realise some very promising buildings <strong>of</strong><br />

their own.<br />

July/August 2007, Pr<strong>of</strong>ile No 188<br />

4dsocial: Interactive Design Environments<br />

Guest-edited by Lucy Bullivant<br />

A new breed <strong>of</strong> social interactive design is taking root that overturns the traditional approach to artistic<br />

experience. Architects and designers are responding to cues from forward-thinking patrons <strong>of</strong> architecture<br />

and design for real-time interactive projects, and are creating schemes at very different scales and<br />

in many different guises. They range from the monumental – installations that dominate public squares<br />

or are stretched over a building’s facade – to wearable computing. All, though, share in common the<br />

ability to draw in users to become active participants and co-creators <strong>of</strong> content, so that the audience<br />

becomes part <strong>of</strong> the project.<br />

4dsocial: Interactive Design Environments investigates further the paradoxes that arise when a new form<br />

<strong>of</strong> ‘socialisation’ is gained through this new responsive media at a time when social meanings are in<br />

flux. While many works critique the narrow public uses <strong>of</strong> computing to control people and data, and<br />

raise questions about public versus private space in urban contexts, how do they succeed in not just getting<br />

enough people to participate, but in creating the right ingredients for effective design?<br />

September/October 2007, Pr<strong>of</strong>ile No 189<br />

Rationalist Traces<br />

Guest-edited by Andrew Peckham, Charles Rattray and Torsten Schmiedenecht<br />

Modern European architecture has been characterised by a strong undercurrent <strong>of</strong> rationalist thought.<br />

Rationalist Traces aims to examine this legacy by establishing a cross-section <strong>of</strong> contemporary European<br />

architecture, placed in selected national contexts by critics including Akos Moravanszky and Josep Maria<br />

Montaner. Subsequent interviews discuss the theoretical contributions <strong>of</strong> Giorgio Grassi and OM Ungers,<br />

and a survey <strong>of</strong> Max Dudler and De Architekten Cie’s work sets out a consistency at once removed from<br />

avant-garde spectacle or everyday expediency. Gesine Weinmiller’s work in Germany (among others) <strong>of</strong>fers<br />

a considered representation <strong>of</strong> state institutions, while elsewhere outstanding work reveals different<br />

approaches to rationality in architecture <strong>of</strong>ten recalling canonical Modernism or the ‘Rational<br />

<strong>Architecture</strong>’ <strong>of</strong> the later postwar period. Whether evident in patterns <strong>of</strong> thinking, a particular formal<br />

repertoire, a prevailing consistency, or exemplified in individual buildings, this relationship informs the<br />

mature work <strong>of</strong> Berger, Claus en Kaan, Ferrater, Zuchi or Kollh<strong>of</strong>f. The buildings and projects <strong>of</strong> a younger<br />

generation – Garcia-Solera, GWJ, BIQ, Bassi or Servino – present a rationalism less conditioned by a concern<br />

to promote a unifying aesthetic. While <strong>of</strong>ten sharing a deliberate economy <strong>of</strong> means, or a sensual<br />

sobriety, they present a more oblique or distanced relationship with the defining work <strong>of</strong> the 20th century.

Architectural Design<br />

March/April 2007<br />

4<br />

<strong>Landscape</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong><br />

Site/Non-Site<br />

Guest-edited by<br />

Michael Spens

ISBN-13 9780470034798<br />

ISBN-10 0470034793<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>ile No 186<br />

Vol 77 No 2<br />

Editorial Offices<br />

International House<br />

Ealing Broadway Centre<br />

London W5 5DB<br />

T: +44 (0)20 8326 3800<br />

F: +44 (0)20 8326 3801<br />

E: architecturaldesign@wiley.co.uk<br />

Editor<br />

Helen Castle<br />

Production Controller<br />

Jenna Brown<br />

Project Management<br />

Caroline Ellerby<br />

Design and Prepress<br />

Artmedia Press, London<br />

Printed in Italy by Conti Tipocolor<br />

Advertisement Sales<br />

Faith Pidduck/Wayne Frost<br />

T +44 (0)1243 770254<br />

E fpidduck@wiley.co.uk<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Will Alsop, Denise Bratton, Mark Burry, André<br />

Chaszar, Nigel Coates, Peter Cook, Teddy Cruz,<br />

Max Fordham, Massimiliano Fuksas, Edwin<br />

Heathcote, Michael Hensel, Anthony Hunt,<br />

Charles Jencks, Jan Kaplicky, Robert Maxwell,<br />

Jayne Merkel, Michael Rotondi, Leon van Schaik,<br />

Neil Spiller, Ken Yeang<br />

Contributing Editors<br />

Jeremy Melvin<br />

Jayne Merkel<br />

All Rights Reserved. No part <strong>of</strong> this publication<br />

may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system<br />

or transmitted in any form or by any means,<br />

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording,<br />

scanning or otherwise, except under the terms<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988<br />

or under the terms <strong>of</strong> a licence issued by the<br />

Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham<br />

Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the<br />

permission in writing <strong>of</strong> the Publisher.<br />

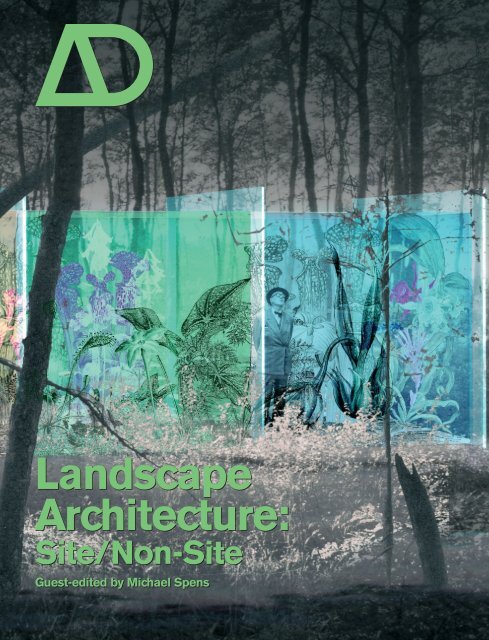

Front cover: Gross.Max, Garden for a Plant<br />

Collector at the House for an Art Lover, Glasgow,<br />

Scotland, 2005 – © Gross.Max<br />

Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to:<br />

Permissions Department,<br />

John Wiley & Sons Ltd,<br />

The Atrium<br />

Southern Gate<br />

Chichester,<br />

West Sussex PO19 8SQ<br />

England<br />

F: +44 (0)1243 770571<br />

E: permreq@wiley.co.uk<br />

Subscription Offices UK<br />

John Wiley & Sons Ltd<br />

Journals Administration Department<br />

1 Oldlands Way, Bognor Regis<br />

West Sussex, PO22 9SA<br />

T: +44 (0)1243 843272<br />

F: +44 (0)1243 843232<br />

E: cs-journals@wiley.co.uk<br />

[ISSN: 0003-8504]<br />

4 is published bimonthly and is available to<br />

purchase on both a subscription basis and as<br />

individual volumes at the following prices.<br />

Single Issues<br />

Single issues UK: £22.99<br />

Single issues outside UK: US$45.00<br />

Details <strong>of</strong> postage and packing charges<br />

available on request.<br />

Annual Subscription Rates 2007<br />

Institutional Rate<br />

Print only or Online only: UK£175/US$315<br />

Combined Print and Online: UK£193/US$347<br />

Personal Rate<br />

Print only: UK£110/US$170<br />

Student Rate<br />

Print only: UK£70/US$110<br />

Prices are for six issues and include postage<br />

and handling charges. Periodicals postage paid<br />

at Jamaica, NY 11431. Air freight and mailing in<br />

the USA by Publications Expediting Services<br />

Inc, 200 Meacham Avenue, Elmont, NY 11003<br />

Individual rate subscriptions must be paid by<br />

personal cheque or credit card. Individual rate<br />

subscriptions may not be resold or used as<br />

library copies.<br />

All prices are subject to change<br />

without notice.<br />

Postmaster<br />

Send address changes to 3 Publications<br />

Expediting Services, 200 Meacham Avenue,<br />

Elmont, NY 11003<br />

C O N T E N T S<br />

4<br />

4<br />

Editorial<br />

Helen Castle<br />

6<br />

Introduction<br />

Site/Non-Site:<br />

Extending the Parameters in<br />

Contemporary <strong>Landscape</strong><br />

Michael Spens<br />

12<br />

From Mound to Sponge:<br />

How Peter Cook Explores<br />

<strong>Landscape</strong> Buildings<br />

Michael Spens<br />

16<br />

New Architectural Horizons<br />

Juhani Pallasmaa<br />

24<br />

Recombinant <strong>Landscape</strong>s<br />

in the American City<br />

Grahame Shane<br />

36<br />

Urban American <strong>Landscape</strong><br />

Jayne Merkel<br />

48<br />

Toronto Waterfront Revitalisation<br />

Sean Stanwick<br />

52<br />

Operationalising Patch Dynamics<br />

Victoria Marshall and<br />

Brian McGrath

60<br />

Recent Works by Bernard Lassus<br />

Michel Conan<br />

66<br />

Deep Explorations Into<br />

Site/Non-Site:<br />

The Work <strong>of</strong> Gustafson Porter<br />

Michael Spens<br />

76<br />

‘Activating Nature’:<br />

The Magic Realism <strong>of</strong><br />

Contemporary <strong>Landscape</strong><br />

<strong>Architecture</strong> in Europe<br />

Lucy Bullivant<br />

88<br />

<strong>Landscape</strong>s <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Second Nature:<br />

Emptiness as a Non-Site Space<br />

Michael Spens<br />

98<br />

City in Suspension: New Orleans<br />

and the Construction <strong>of</strong> Ground<br />

Felipe Correa<br />

106<br />

Impressions <strong>of</strong> New Orleans<br />

Christiana Spens<br />

109<br />

Is There a Digital Future<br />

<strong>Landscape</strong> Terrain?<br />

Lorens Holm and<br />

Paul Guzzardo<br />

4+<br />

114+<br />

Interior Eye<br />

Seoul’s Interior <strong>Landscape</strong>s<br />

Howard Watson<br />

120+<br />

Building Pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

Louise T Blouin Institute,<br />

West London<br />

Jeremy Melvin<br />

126+<br />

Practice Pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

The Tailored Home: Housebrand<br />

Loraine Fowlow<br />

134+<br />

Home Run<br />

Dosson in Casier, Italy<br />

Valentina Croci<br />

140+<br />

McLean’s Nuggets<br />

Will McLean<br />

142+<br />

Site Lines<br />

Night Pilgrimage Chapel<br />

Laura M<strong>of</strong>fatt

Alison and Peter Smithson, Upper Lawn Pavilion, Fonthill, Wiltshire, UK, 1959–<br />

View through the patio window to the Fonthill woods to the north, 1995, taken after the Smithsons left Fonthill. The<br />

Smithsons’ placemaking skills are evident in the domestic tranquility that their architecture here evokes.<br />

4

Editorial<br />

If the museum was the architectural leitmotif <strong>of</strong> the turn <strong>of</strong> the millennium, it has been eclipsed in<br />

the noughties by landscape architecture. As guest-editor Michael Spens so aptly brings to our<br />

attention in the introduction to this issue, it is the planet’s ecological plight and the confinement <strong>of</strong><br />

people to an ever shrinking natural world that has jettisoned landscape architecture – within a<br />

matter <strong>of</strong> a decade – from a discipline responsible for creating elitist ‘Arcadias’ to that <strong>of</strong> much<br />

sought-after human ‘sanctuaries’. Whether situated on urban, suburban or greenfield sites, these<br />

sanctuaries are very much for public consumption (or at least semi-public when attached to an<br />

institution or corporation). Certainly they are not like the landscaped estates <strong>of</strong> the 18th century,<br />

land that was partitioned <strong>of</strong>f for the appreciation <strong>of</strong> all but the smallest ruling elite. Whether the<br />

schemes featured here are situated in Beirut, Singapore, New York, Toronto or Birmingham, they<br />

engender a sense <strong>of</strong> place that is precious in its provision <strong>of</strong> outdoor space for increasingly<br />

displaced urban populations, but also enriching in terms <strong>of</strong> a city’s political and socioeconomic<br />

kudos. The design for Toronto’s waterfront, for instance, led by Adriaan Geuze and West 8, is to<br />

reclaim a continuous promenade at the edge <strong>of</strong> Lake Ontario for which three levels <strong>of</strong> government<br />

have pledged $20.1 million for the first phase <strong>of</strong> construction. This is the tail end <strong>of</strong> the statesponsored<br />

‘Superbuild’ programme that has commissioned a college <strong>of</strong> art from Will Alsop, a<br />

substantial reworking <strong>of</strong> the Art Gallery <strong>of</strong> Toronto by Frank Gehry, and a makeover <strong>of</strong> the Royal<br />

Ontario Museum by Daniel Libeskind.<br />

It is all too easy to regard landscape architecture as an entirely new episode – severed from any<br />

previous tectonic or artistic roots. In his introduction, Spens poignantly corrects this notion by<br />

tracing the lineage <strong>of</strong> landscape architecture’s expanded field from the Land Art <strong>of</strong> the 1970s,<br />

which effectively dispelled architecture’s obsession with buildings as objects. An understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

the potential <strong>of</strong> the landscape art <strong>of</strong> the picturesque for architecture was, though, latent even in the<br />

postwar period. As Jonathan Hill has pointed out, Alison and Peter Smithson were influenced by<br />

Nikolaus Pevsner’s promotion <strong>of</strong> the picturesque. 1 For them, the picturesque placed the emphasis<br />

on the observer giving meaning. It was about perception and the genius <strong>of</strong> place making. This is<br />

most evident at Fonthill in Wiltshire where the Smithsons bought a cottage in the estate <strong>of</strong> the<br />

ruined folly. The new house they built there was in no way intended to be authentic; one window<br />

was displaced to create the garden wall. Life there, though, was described by Alison Smithson as<br />

‘Jeromian’, evoking with its serenity and air <strong>of</strong> studious calm Antonello da Messina’s St Jerome in<br />

His Study (National Gallery, c 1475). It was this triumph <strong>of</strong> atmosphere over form that was<br />

prophetic for 21st-century landscape.<br />

Helen Castle<br />

Note<br />

1. I am indebted to Jonathan Hill for his observations in his paper ‘Ambiguous Objects: Modernism, Brutalism and the Politics <strong>of</strong> the Picturesque’ , presented at<br />

the 3rd annual Architectural Humanities Research Association International Conference, St Catherine’s College, Oxford, 17–18 November 2006), and also for his<br />

help sourcing this fascinating photograph from Georg Aerni.<br />

Text © 2007 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Image © Georg Aerni<br />

5

Introduction<br />

Site/Non-Site<br />

Extending the Parameters in<br />

Contemporary <strong>Landscape</strong><br />

As the world teeters on the verge <strong>of</strong> environmental collapse, landscape architecture has taken<br />

on a new significance <strong>of</strong>fering a longed-for sanctuary for our increasingly urbanised lives. Here,<br />

in his introduction to the issue, guest-editor Michael Spens explains how by taking its impetus<br />

from land art, landscape architecture, as an expanded field, transcends the conventional<br />

confines <strong>of</strong> site. This renders it possible to read architecture ‘as landscape, or as nonlandscape,<br />

as building becomes non-site’ and the ‘site indeed materialises as the work per se’.<br />

6

To assume a critical standpoint in landscape design today<br />

requires the jettisoning <strong>of</strong> all inherited precepts, necessarily<br />

in the global context where environmental design is<br />

transformed into a form <strong>of</strong> disaster management. Our 21stcentury<br />

confinement, where humanity becomes increasingly<br />

entrapped, enclosed and endangered, marks a tragic<br />

condition. In the late l990s, the Swiss landscape designer<br />

Dieter Kienast appropriated from a Latin tomb text the phrase<br />

Et in Arcadia, Ego to illustrate the dilemma facing landscape<br />

designers. ‘I equate Arcadia with the longing always to be<br />

somewhere else. … I am sure this longing to escape from all<br />

our problems exists in all <strong>of</strong> us.’ 1<br />

Sanctuary has now replaced Arcadia as a destination, and<br />

without the dreams. Land art has now elaborated the<br />

conceptual vacuum <strong>of</strong> the l980s, as John Dixon Hunt claims,<br />

bringing as process ‘its invocation <strong>of</strong> abstraction and its<br />

confidence in its own artistry.’ 2 In this issue <strong>of</strong> AD, Juhani<br />

Pallasmaa demonstrates how ideas come to haunt the cultural<br />

appropriations <strong>of</strong> terrain, and in Dixon Hunt’s view this representation<br />

<strong>of</strong> land as art is now a fundamental ambition <strong>of</strong><br />

the landscape architect today. We are wise to abandon all such<br />

Arcadian visions, aware as architects, landscape designers and<br />

land artists that we inhabit a fragmented disaster zone. New<br />

Orleans, post-Katrina, shows how it remains both the butt and<br />

the paradigm <strong>of</strong> this tragic condition.<br />

In the past decade, the role <strong>of</strong> landscape design has<br />

experienced a veritable global transformation. While<br />

‘environment’ has become the flag <strong>of</strong> convenience under<br />

which a wide variety <strong>of</strong> proprietorial and intellectual vessels<br />

sail, this usage has tacitly recognised the occlusion <strong>of</strong><br />

buildings with landscape architecture, for its predominant<br />

role in designing on a particular site. The recent 2006<br />

International Architectural Biennale in Venice revealed full<br />

well the confusion that reigns. Director Ricky Burdett’s focus<br />

on urban landscapes as such demonstrated the absence <strong>of</strong><br />

architecture itself from its historically predominant position,<br />

notwithstanding such successful ventures as the upgraded<br />

spaces in Bogotá. This is a dilemma that has been forming<br />

stealthily for most <strong>of</strong> this decade.<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> key markers have pointed towards fresh<br />

directions for the recovery <strong>of</strong> the urban landscape. For<br />

example, Hiroki Hasegawa’s Yokohama Portside Park in Japan<br />

(1999) was quick to exploit its waterside location. 3 In this city<br />

zone <strong>of</strong> mixed-use development, earthwork berms were<br />

designed to run along the full length <strong>of</strong> the waterfront, thus<br />

‘oceanic’ identity was merged with the purely urban<br />

connotation <strong>of</strong> the site. Hasegawa created a series <strong>of</strong><br />

sequential layers that gave the location a strong identity.<br />

Very small-scale landscape detailing, such as cobbles, setts<br />

(granite paving blocks) and larger pavings, was combined<br />

with steel elements, wooden decking and brick open spaces,<br />

Hans Hollein, Museum <strong>of</strong> Vulcanology, Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2005<br />

<strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>of</strong> the underground, looking down into the museum from ground level.<br />

worked in with grassed lawns and mounds. Materiality was<br />

clearly conceived and expressed.<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> the later schemes reviewed in this issue<br />

demonstrate similarities with Hasegawa’s groundbreaking<br />

project; for example, Gustafson and Porter’s urban<br />

redefinition <strong>of</strong> Singapore. And the completely landlocked<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Vulcanology, by Hans Hollein, in northeastern<br />

France, 4 expounds a philosophy <strong>of</strong> building a landscape<br />

concept on site, where the key elements are located<br />

underground. But as Hollein has always said: ‘Alles ist<br />

architektur’. This building is nothing if not architecture. He<br />

also explored well the ramifications <strong>of</strong> such deep engagement<br />

with the site in previous projects, such as the Museum<br />

Abteilberg in Mönchengladbach, Germany (1980)and the<br />

proposed Guggenheim Museum in Salzburg, Austria (1985).<br />

In 1993, Juhani Pallasmaa, at Aleksanterinkatu (the famous<br />

street in the centre <strong>of</strong> Helsinki), activated this small interstitial<br />

site with his own structural inventiveness using new<br />

installations, again focusing on their materiality to infuse a<br />

degree <strong>of</strong> poetics into a wind-blown pedestrian space between<br />

high blocks. 5 For a very much more expansive urban space,<br />

that designed by Dixon and Jones for London’s Exhibition Road<br />

(‘a key cultural ‘entrepôt’ adjacent to the Victoria and Albert<br />

Museum), there can be no limit, other than the constraints <strong>of</strong><br />

civic bureaucracies, to the insertion <strong>of</strong> a wholly different,<br />

vehicle-free urban perspective where people can actually jog<br />

and walk unimpeded. In a similar mode but on a far smaller<br />

scale at Whiteinch Cross, Glasgow Green (1999), Gross.Max<br />

coordinated installations <strong>of</strong> varying materials with carefully<br />

judged tree planting 6 and secluded seating areas.<br />

The urban spaces <strong>of</strong> Bogotá remain endemically detrimental to normal urban living criteria, and as purely temporary<br />

shelters have lasted for decades.<br />

7

The most dramatic case <strong>of</strong> the expanded field itself where site<br />

and non-site mediate the urban topography is expressed in Peter<br />

Eisenman’s masterly design for the extensive range <strong>of</strong> cultural<br />

and arts facilities for the historic city <strong>of</strong> Santiago de Compostela<br />

in Spain. Eisenman, who has for many years experimented with<br />

orthogonal grid-planning, overlaid the whole site with an<br />

undulating carpet thrown over the various functions below, like<br />

a new landscape. The non-site characteristics are elegantly<br />

exemplified by this wrap <strong>of</strong> fully grounded digital renderings<br />

formulated as an extensive sanctuary for those it welcomes. A<br />

project such as this draws together all the preoccupations <strong>of</strong><br />

contemporary architects, which have tended to be less easily<br />

resolved than those <strong>of</strong> contemporary landscape architects, in<br />

this new procedure <strong>of</strong> transition.<br />

In all <strong>of</strong> the schemes above, the realm <strong>of</strong> architectural<br />

engagement was conditioned by the realisation that landscape<br />

design and architecture are no longer inhibited by outmoded<br />

site contextualities. A way had been opened by contemporary<br />

artists and sculptors to liberate space, in terms <strong>of</strong> an ‘expanded<br />

field’. As early as 1970 Robert Morris effectively redefined<br />

minimalist sculpture in his Notes on Sculpture II, in which he<br />

‘disposed once and for all with the object as such varying<br />

conditions <strong>of</strong> light and spatial context’. 7 Site-specifics, as it<br />

became known, was equally relevant to architecture and<br />

landscape, in both public and private spaces, pursuing a clear<br />

minimalism. What was surprising was the amount <strong>of</strong> time it<br />

took for such concepts from art to take root in the associated<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> architecture and <strong>of</strong> landscape. It was in the same year,<br />

too, that Robert Smithson created his Spiral Jetty project in<br />

Utah (which actually disappeared owing to variations in the<br />

water regime locally, and then equally miraculously reappeared<br />

in the bewildering climatic context <strong>of</strong> the new century).<br />

Sculptors as such resented the onset <strong>of</strong> minimalism since<br />

the majority still wanted to produce works that were wholly<br />

Peter Eisenman Architects, City <strong>of</strong> Culture, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 1999–<br />

For this planned City <strong>of</strong> Culture, Eisenman designed an undulating, shrouded landscape, creating for the complex a<br />

new yet coherent morphology that is entirely complementary to the existing historic city.

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, Great Salt Lake, Utah, 1970<br />

This seminal ‘site/non-site’ installation sculpture in the bereft landscape <strong>of</strong> the Great Salt Lake exemplified Smithson’s<br />

groundbreaking realisations <strong>of</strong> the late 1960s. Dramatically, in the ensuing decades, it actually disappeared below the<br />

water surface owing to microclimatic changes in the Great Salt Lake area, but the in 2005 suddenly re-emerged from<br />

the water as the lake level again subsided. Smithson may not have anticipated this almost apocryphal occurrence, but<br />

it was timely given global preoccupations with climate change and its effects today.<br />

engaged with context. By contrast, site-specific works as well<br />

as land art and earthworks, by refusing object ‘status’, spread<br />

out the minimalist involvement with site, and as can now be<br />

observed operated more and more effectively as ideological<br />

frontrunners for both architecture and landscape. ‘Notarchitecture’<br />

coalesced with ‘not-landscape’. A quaternary<br />

model <strong>of</strong> opposites was derived (following earlier binary,<br />

Klein group oppositions) 8 combining site and non-site,<br />

succinctly exemplified, as it turned out, by Smithson’s Spiral<br />

Jetty. An axiomatic structure had emerged. The expansion <strong>of</strong><br />

the field was permanent.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the reasons why all this took time to be accepted by<br />

landscape designers was their detachment as a pr<strong>of</strong>ession. Even<br />

more so and equally out on a limb, some architects also had<br />

difficulty in abandoning the objective <strong>of</strong> the site-specific<br />

‘signature’ building. After all, success for architects has<br />

primarily been measured by the landmark building. In addition,<br />

the wave <strong>of</strong> confusion as to what constituted ‘Postmodernism’<br />

complicated developments. There were, <strong>of</strong> course, different<br />

Postmodernisms: for example, ‘Neo-Con’ Postmodernism<br />

(which still sputters) was really Anti-Modernist. This was also<br />

the dilemma <strong>of</strong> architects and landscape designers, in what<br />

now, in retrospect, reads as a wholly detached field <strong>of</strong> theory.<br />

But <strong>of</strong> course it was not, or should not have been so.<br />

For the pr<strong>of</strong>essions <strong>of</strong> landscape architects and architects,<br />

despite pioneering teaching and research at the University <strong>of</strong><br />

Pennsylvania Graduate <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> Fine Arts and the development<br />

<strong>of</strong> a wide-ranging landscape curriculum by the late Ian McHarg,<br />

by John Dixon-Hunt and, lately, by James Corner, few schools<br />

made the transformation that was required. It is only in the<br />

past decade that talent from the such schools, chiefly in the US,<br />

has begun to take effect in new practice.<br />

9

Dixon and Jones Architects, Exhibition Road, London, 2005/06<br />

The project shows how a busy traffic thoroughfare can be diverted into a potential cultural role <strong>of</strong> major significance.<br />

This issue <strong>of</strong> AD specifically recognises the precedent <strong>of</strong><br />

such groundbreaking adjustments in art theory, and so to<br />

architectural and landscape theory, which engendered the<br />

transformation whereby architecture has become readable as<br />

landscape, or as non-landscape, as building becomes non-site:<br />

site indeed materialises as the work per se. Viewing the work<br />

<strong>of</strong> Bernard Lassus, as described by Michel Conan, and taking<br />

in Gross.Max’s image on this cover, a contrasting parody<br />

emerges <strong>of</strong> the larger predicament, containing the just<br />

perceptible figures <strong>of</strong> both Mies van der Rohe and Le<br />

Corbusier, stumbling in the landscape undergrowth like<br />

discarded souls – which is just where unreconstructed<br />

Modernism left society. Lassus and Peter Cook emerge as<br />

longstanding frontrunners in the process <strong>of</strong> re-envisaging the<br />

future <strong>of</strong> landscape design in both the urban and the rural<br />

contexts, which today have become inseparable.<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> praxis, the two in-depth case studies included<br />

in the issue – the current work <strong>of</strong> Kathryn Gustafson and<br />

Neil Porter in Beirut and now proposed for Singapore, and<br />

Florian Beigel and Philip Christou in Leipzig and Korea –<br />

indicate how the application <strong>of</strong> this ethos in landscapes <strong>of</strong><br />

varying narratives, both archaeological and botanical,<br />

pursues this quarternary set <strong>of</strong> objectives, the tapestry <strong>of</strong><br />

both futures and pasts.<br />

10

Juhani Pallasmaa’s key essay articulates the ways in which<br />

architects and landscape designers analyse the pretext for<br />

architecture as a median in remembered landscape, and<br />

draws out the creative initiatives that persist throughout the<br />

visual arts as linkages, so refuting once and for all the<br />

separation and superiority <strong>of</strong> such a domain once assumed by<br />

architects for themselves.<br />

Grahame Shane’s work on the recombinant city landscape,<br />

as described in his article, has far-reaching consequences. He<br />

takes up the issue <strong>of</strong> the American regional cityscape where<br />

compressed patches have become rhizomatic assemblages <strong>of</strong><br />

highly contrasting urban fragments and landscape parcels,<br />

the North American city remaining still a patchwork <strong>of</strong><br />

landscape scenarios and codes – the automobile being itself<br />

the device that recodifies the urban–rural relationship. Shane<br />

seeks out James Corner’s key role, as successor to Ian McHarg<br />

at the University <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania, and thus <strong>of</strong> Patrick Geddes,<br />

whose ecological research early in the 20th century separated<br />

out rural and urban regional systems by layers, a process that<br />

was in turn computerised by McHarg. Shane concludes that<br />

landscapes were created as a scenographic element in plotting<br />

marketing locations in the global media ecology, rather than<br />

structurally engaging in a ecological process.<br />

Following up this clear appraisal, Lorens Holm and Paul<br />

Guzzardo assess the potential for a digitalisation and reformulation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the site/non-site parameters in the prevailing<br />

urban/rural scenario. They use the metaphor <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Mississippian lost or abandoned city <strong>of</strong> Cahokin, seen like a<br />

laser\net narrative creation for today. The consequent focus<br />

on the defoliation <strong>of</strong> rural cultures and global warming<br />

epitomises, to the authors, a ‘style’ <strong>of</strong> today, and accepts the<br />

end-result possibility <strong>of</strong> environmental death. Holm and<br />

Guzzardo anticipate a ‘digital future landscape terrain’,<br />

utilising laser/net technology, as a synthesis for a new<br />

awareness. Technology is harnessed to good effect, to protect<br />

and reformulate landscape ecologies.<br />

But disasters are already upon us. One catastrophe has<br />

threatened (but physically also narrowly veered away)<br />

Gustafson and Porter’s Shoreline plan for the sea edge to the<br />

historic core <strong>of</strong> Beirut City. This threat was entirely manmade.<br />

The second catastrophe addressed, with great<br />

foreboding but in mind <strong>of</strong> a future recovery, is described by<br />

Felipe Correa: the case <strong>of</strong> New Orleans. After a long pause (the<br />

human consequences were exacerbated by a protracted<br />

history <strong>of</strong> social and physical neglect <strong>of</strong> ‘The Big Easy’),<br />

measures are at last being put in place. But meantime, as with<br />

the early city <strong>of</strong> Cahokin, the mystery is how half the<br />

population has literally vanished upstate and beyond. Also<br />

included in the issue is a short, illustrated eye-witness<br />

summary <strong>of</strong> the after effects <strong>of</strong> the hurricane by a student,<br />

which brings the experience on site for all to recognise in its<br />

severity. Is this a paradigm for a new global effect – the<br />

disintegration <strong>of</strong> hope?<br />

The twin surveys <strong>of</strong> US design and that in Europe by Jayne<br />

Merkel and Lucy Bullivant provide at last some<br />

encouragement for the 21st century. <strong>Landscape</strong> designers,<br />

architects, engineers and ecologists are increasingly working<br />

together to define and implement new solutions, working on<br />

the front line.<br />

One thing here is certain, that pretext, context and subtext<br />

have all transmogrified, and architects and landscape<br />

designers, like the visual artists who have been the<br />

pathfinders and scouts for this enterprise, need to seek wholly<br />

different solutions. The surveys here <strong>of</strong>fer new, divergent<br />

directions, yet both fields are suffused with their own poetics,<br />

as Pallasmaa has urged. Poetry is alive and well and the<br />

poetics are not least evident in the major new international<br />

projects referred to above, the chief abiding hope for salvation<br />

in the laser\net world <strong>of</strong> today.<br />

Notes<br />

1. Dieter Kienast, in Udo Weilacher, Between <strong>Landscape</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> and Land<br />

Art, Birkhauser (Basel), 1999, pp 152–4.<br />

2. John Dixon Hunt, ‘Introduction’ in ibid, pp 6–7.<br />

3. Michael Spens, Modern <strong>Landscape</strong>, Phaidon (London), 2003, pp 48–51.<br />

4. Ibid, pp 92–7.<br />

5. Ibid, pp 187–91.<br />

6. Ibid, pp 192–7.<br />

7. See Hal Foster, Rosalind Kraus, Yve-Alain Bois and Benjamin Buchloh, Art<br />

Since l900, Thames & Hudson (London), 2004, pp 358 and 540–2.<br />

8. Ibid, pp 543–4.<br />

Gross.Max, Whiteinch Cross, Glasgow, Scotland, 1999<br />

A drawn overview <strong>of</strong> the scheme showing the correlation <strong>of</strong> various elements.<br />

Eelco Ho<strong>of</strong>tman <strong>of</strong> Gross.Max here placed great importance on the weaving<br />

together, in a tight urban environment, <strong>of</strong> hard and s<strong>of</strong>t landscape elements.<br />

Text © 2007 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Images: p 6 © DigitalGlobe, exclusive<br />

distributed for Europe by Telespazio; p 7 © Studio Hollein/Sina Baniahmad; p<br />

8 © courtesy <strong>of</strong> Eisenman Architects; p 9 © Estate <strong>of</strong> Robertson<br />

Smithson/DACS, London/VAGA, New York, 2007. Image courtesy James<br />

Cohan Gallery, New York. Collection: DIA Center for the Arts, New York. Photo<br />

Gianfranco Gorgoni; p 10 © English Heritage. NMR; p 11 © Gross.Max<br />

11

From Mound to Sponge<br />

How Peter Cook Explores <strong>Landscape</strong> Buildings<br />

While his fellow Archigram designers were hooked into new<br />

technologies, Peter Cook was heading his own private<br />

investigation into landscape. Michael Spens traces<br />

Cook’s preoccupation with site from the aptly named<br />

Mound <strong>of</strong> 1964 through to his Sponge City<br />

earthscape <strong>of</strong> 1974. The project continues<br />

with Cook’s recent Oslo Patch.<br />

Peter Cook, Sponge City, 1974<br />

Sponge City, otherwise known as ‘the Sponge<br />

Building’, provided a dramatic and radical<br />

intervention in architectural debate when it was<br />

first presented by Cook in 1975 at ‘Art Net’, his<br />

architecture gallery in London. The project<br />

turned on their heads previous<br />

assumptions about the pre-eminence<br />

<strong>of</strong> buildings over the landscape field.

Oslo Patch<br />

Peter Cook<br />

The historical trail blazed by the Archigram group (Peter Cook,<br />

Ron Herron, Dennis Crompton, David Green and Warren<br />

Chalk, plus Michael Webb) through the 1960s and 1970s was<br />

duly recognised and honoured in 2004 by the award <strong>of</strong> the<br />

RIBA Gold Medal <strong>of</strong> that year. However, Peter Cook has also<br />

pursued, perhaps as a separate vein <strong>of</strong> intellectual therapy or<br />

maybe <strong>of</strong> inspiration, his own trail <strong>of</strong> engagement with<br />

buildings in the landscape, running parallel to the great<br />

Archigram arc in the sky. Though extremely interesting, this<br />

work has seldom been exposed to a public dazzled by the<br />

instant Walking Cities, such as Ron Herron’s Cities Moving<br />

and Cook’s Plug-in City (both 1964), as well as Dennis<br />

Crompton’s Computer City (1965). But where was the actual<br />

landscape, Cook seems uniquely, and privately, to have asked?<br />

Somewhat hidden from posterity, there emerged from Cook<br />

a project simply entitled Mound (1964). Cook here followed a<br />

clear brief, to sink the building into the ground, as a multi-use<br />

centre, covered with grass banks. The brief included ‘open<br />

space’, designated external high-up recreational space with a<br />

c<strong>of</strong>fee shop, plaza, shopping malls, a cinema/auditorium, ad<br />

infinitum as the grass grew overhead. It was, <strong>of</strong> course, plugged<br />

into a monorail, with a station on level 5, and was inherently<br />

as inward looking as the Archigram projects had been<br />

extrovert and attention seeking. But this was not the mood <strong>of</strong><br />

the time, however advanced and prescient <strong>of</strong> contemporary<br />

trends the scheme has turned out to be.<br />

His Sponge City project (1974) was another attempt at the<br />

philosophy <strong>of</strong> the building as landscape, or the building as<br />

enveloped by natural site coverage. This was presented more<br />

dramatically, and exhibited at the privately sponsored ‘Art<br />

Net’ centre (1975) in central London, which Cook developed<br />

largely due to his chagrin at not being appointed director <strong>of</strong><br />

the Institute <strong>of</strong> Contemporary Arts. Six panels, each 5 metres<br />

(16 feet) long and 2 metres (6.5 feet) high were conjoined in a<br />

blaze <strong>of</strong> coloured relief. Sponge City was, <strong>of</strong> course, influenced<br />

by Cook’s teachings during the 1970s at the Architectural<br />

Association, where students such as Will Alsop, influenced by<br />

Cedric Price, and later by Alvin Boyarsky, were beginning to<br />

search out a more ‘organic’ community than had been<br />

portrayed by the mechanistic Archigram dreams now <strong>of</strong> a<br />

decade earlier.<br />

Sponge City represented a dramatic new intervention by<br />

Cook in contemporary thinking about cities and their<br />

fragments. However prescient and predictive <strong>of</strong> the directions<br />

that land–site–building might follow over the next 30 years, it<br />

was constructed in the realisation <strong>of</strong> Cook’s own theories,<br />

anticipating first and foremost community living, up to seven<br />

storeys high, nestling in a lush and accommodating<br />

earthscape. What Cook defined as ‘the Sponge condition’ was<br />

clearly articulated in plan, with a skin, orifices, ‘gunge’<br />

openings, areas <strong>of</strong> elasticity and an articulate inner core<br />

structure with elevators and a ‘latch-on’ arrangement<br />

between hard-core elements and s<strong>of</strong>t sponge surrounds<br />

designed to incorporate ‘nests’ with the latch-on. Two high<br />

mounds were integrated within the ‘Sponge’, overlapping and<br />

incorporating remnant arched colonnades (possibly for<br />

historical memory traces) and quasi-classical fenestration. The<br />

elevation also included a collage, descriptive <strong>of</strong> ‘lifestyles’ and<br />

realised electronically in billboard form.<br />

No other late 20th-century design exercise better opened<br />

up the potential <strong>of</strong> ‘site/non-site’ – by then a main area <strong>of</strong><br />

interest for artists such as Robert Smithson. Sponge City was<br />

an environmental projection that was also quite clearly<br />

divergent from conventional thinking – even tangential<br />

beyond the pure Archigram mode – in which Cook was<br />

exploring and forecasting the many possible ways in which<br />

14

The Oslo Patch investigates a new way in which a large tract <strong>of</strong><br />

railway yards and busy railway lines can be inhabited. The location<br />

is close to downtown, but rather barren. Behind it lie some inner<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> mixed-use; the other side is almost at the edge <strong>of</strong> the fjord.<br />

A key interpretation is the avoidance <strong>of</strong> the boring formula <strong>of</strong><br />

draping the whole thing with a deck. Rather, there is a lacework <strong>of</strong><br />

waving strips <strong>of</strong> housing, allowing a wide variety <strong>of</strong> drapes,<br />

parasites and add-ons. Interlaced with these are a series <strong>of</strong><br />

vegetated and partially vegetated strips. On other axes are other<br />

strips <strong>of</strong> walkway. Underneath all <strong>of</strong> this – yet largely exposed – are<br />

the rail tracks themselves.<br />

The whole is thus a complex series <strong>of</strong> layered strips. A canal is<br />

brought in under cover into an ‘arcade’ condition. Above are special<br />

high-intensity student dwellings. A small sports and music stadium<br />

is located within the system. Much <strong>of</strong> the vegetation works itself up<br />

the sides <strong>of</strong> the housing buildings.<br />

The drawn project parallels a long section through the site and a<br />

‘collage-cartoon’ strip that identifies a series <strong>of</strong> inspirations from,<br />

and references to, Oslo – inflatables, flags, sports, snow, bridges –<br />

based on my experience <strong>of</strong> the city since 1968.<br />

Peter Cook, Mound, 1964<br />

A multi-use centre, inward-looking and covered with grass banks.<br />

cities could be absorbed within the natural environment.<br />

<strong>Landscape</strong> was here represented as a growing, enfolding<br />

aspect <strong>of</strong> urban expansion, an absorbent city conurbation,<br />

rather than something appropriated by the city.<br />

In 2004 Sponge City re-emerged, at the Design Museum in<br />

London, as the climax to a major Archigram exhibition. Here<br />

Cook pointed clearly to an environment <strong>of</strong> a totally built but<br />

growing landscape, forecasting, this time in the 21st century,<br />

the ways in which cities, or fragments <strong>of</strong> cities, will in future<br />

be absorbed into the proactive, recombinant landscape. As he<br />

wrote recently:<br />

‘The new architecture celebrates the fold-over <strong>of</strong><br />

contrived surface with grasped surface. The new<br />

sensibility is toward terrain rather than patches or<br />

pockets. There is even a search for peace without escape<br />

– difficult for one to imagine amongst the chatter <strong>of</strong> the<br />

old city. … For me it becomes even more intriguing if we<br />

pull the vegetal towards the artificial and the fertile<br />

towards the urban but in the end … to find the magic <strong>of</strong><br />

a place discovered, now that’s architecture.’ 1<br />

Cook’s prognosis takes society along an irreversible course:<br />

firstly, focusing on the ways people relate landscape and<br />

architecture; secondly, developing these strategies in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

‘making place’; and finally, considering the inherent<br />

connections between nature and urbanism. This new<br />

thinking is evident in his proposal for the Oslo waterfront<br />

(The Patch), in which all <strong>of</strong> these preoccupations dramatically<br />

come together, making place for the capital city in a way<br />

hitherto never anticipated – the built elements displaying a<br />

strong and organically tectonic structure with an enigmatic<br />

shrouding <strong>of</strong> membrane.<br />

Cook’s work in this area reveals that it is now time to plot<br />

the evolution <strong>of</strong> a relevant 21st-century preoccupation – the<br />

idea <strong>of</strong> conjoining landscape and architecture as a single,<br />

collusive environment. 4<br />

Note<br />

1. In Catherine Spellman (ed), Re-Envisioning <strong>Landscape</strong>/<strong>Architecture</strong>, Actar<br />

(Barcelona), 2003.<br />

Text © 2007 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Images © Peter Cook<br />

15

New Architectural Horizons<br />

In recent years, the over-intellectualisation <strong>of</strong> architecture has detached it ‘from its<br />

experiential, embodied and emotive ground’. Juhani Pallasmaa provides a template for<br />

architecture and landscape design that enables a stronger continuum between our outer and<br />

inner landscapes, drawing on historic and modern artistic inspirations alike.<br />

Thinking is more interesting than knowing, but less interesting<br />

than seeing.<br />

JW Goethe 1<br />

<strong>Landscape</strong> as a Portrait<br />

We tend to see our external physical landscape <strong>of</strong> life and our<br />

inner landscape <strong>of</strong> the mind as two distinct and separate<br />

categories. As designers we focus our aspirations and values<br />

on the visual qualities <strong>of</strong> our architectural landscape. Yet, the<br />

physical settings that we build constitute an uninterrupted<br />

continuum with our inner world. As the cultural geographer<br />

PF Lewis writes in his introduction in Interpretation <strong>of</strong> Ordinary<br />

<strong>Landscape</strong>s: ‘Our human landscape is our unwitting<br />

autobiography, reflecting our tastes, our values, our<br />

aspirations, and even our fears, in tangible, visible form. We<br />

rarely think <strong>of</strong> landscape that way, and so the cultural record<br />

we have written in the landscape is liable to be more truthful<br />

than most autobiographies, because we are less self-conscious<br />

about how we describe ourselves.’ 2<br />

Jorge Luis Borges gives a poetic formulation to this<br />

interaction between the world and the self: ‘A man sets himself<br />

the task <strong>of</strong> portraying the world. Over the years he fills a given<br />

surface with images <strong>of</strong> provinces and kingdoms, mountains,<br />

bays, ships, islands, fish, rooms, instruments, heavenly bodies,<br />

horses and people. Shortly before he dies he discovers that this<br />

patient labyrinth <strong>of</strong> lines is a drawing <strong>of</strong> his own face.’ 3<br />

We urgently need to understand that we do not live<br />

separately in physical and mental worlds – these two<br />

projections are completely fused into a singular existential<br />

reality. As we design and build physical structures, we are<br />

simultaneously and essentially creating mental structures and<br />

realities. Regrettably, we have not developed much<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> and sensitivity for the interaction <strong>of</strong> our<br />

outer and inner landscapes.<br />

<strong>Architecture</strong>: An Impure Discipline<br />

The complexity <strong>of</strong> the phenomenon <strong>of</strong> architecture results<br />

from its ‘impure’ conceptual essence as a field <strong>of</strong> human<br />

endeavour. <strong>Architecture</strong> is simultaneously a practical and a<br />

metaphysical act – a utilitarian and poetic, technological and<br />

artistic, economic and existential, collective and individual<br />

manifestation. I cannot, in fact, name a discipline possessing a<br />

more complex and essentially more conflicting grounding in<br />

the lived reality and human intentionality. <strong>Architecture</strong> is<br />

essentially a form <strong>of</strong> philosophising by means <strong>of</strong> its<br />

characteristics: space, matter, structure, scale and light,<br />

horizon and gravity. <strong>Architecture</strong> responds to existing<br />

demands and desires at the same time so that it creates its<br />

own reality and criteria – it is both the end and the means.<br />

Moreover, authentic architecture surpasses all consciously set<br />

aims and, consequently, is always a gift <strong>of</strong> imagination and<br />

desire, willpower and foresight.<br />

The Multiplicity <strong>of</strong> Theoretical Approaches<br />

Over the past few decades, numerous theoretical frameworks<br />

originating in various fields <strong>of</strong> scientific enquiry have been<br />

applied to the analyses <strong>of</strong> architecture: perceptual and gestalt<br />

psychologies; anthropological and literary structuralisms;<br />

sociological and linguistic theories; analytical, existential,<br />

phenomenological and deconstructionist philosophies; and,<br />

more recently, cognitive and neurosciences, to name the most<br />

obvious. We have to admit that our discipline <strong>of</strong> architecture<br />

does not possess a theory <strong>of</strong> its own – architecture is always<br />

explained through theories that have arisen outside its own<br />

realm. In the first and the most influential theoretical treatise<br />

in the history <strong>of</strong> Western architecture, Vitruvius acknowledged<br />

already in the first century BC the breadth <strong>of</strong> the architect’s<br />

discipline and the consequent interactions with numerous<br />

skills and areas <strong>of</strong> knowledge: ‘Let him (the architect) be<br />

educated, skilful with the pencil, instructed in geometry, know<br />

much history, have followed the philosophers with attention,<br />

understand music, have some knowledge <strong>of</strong> medicine, know<br />

the opinions <strong>of</strong> the jurists and be acquainted with astronomy<br />

and the theory <strong>of</strong> heavens.’ 4 Vitruvius provides careful reasons<br />

why the architect needs to master each <strong>of</strong> these fields <strong>of</strong><br />

knowledge. Philosophy, for example, ‘makes an architect highminded<br />

and not self-assuming, but rather renders him<br />

courteous, just and honest without avariciousness’. 5<br />

Giorgione, The Tempest, c 1508<br />

Giorgione reveals a site/non-site panorama occupying the middle ground, but leading the eye <strong>of</strong> the viewer right out <strong>of</strong><br />

the painting, with the figures almost floating in the foreground, somehow detached from the storm-bound scene beyond.<br />

17

The Frenzy <strong>of</strong> Theorising<br />

In our time, however, theoretical and verbal explanations <strong>of</strong><br />

buildings have <strong>of</strong>ten seemed more important than their<br />

actual design, and intellectual constructs more important<br />

than the material and sensuous encounter <strong>of</strong> the built works.<br />

The uncritical application <strong>of</strong> various scientific theories to the<br />

field <strong>of</strong> architecture has <strong>of</strong>ten caused more confusion than a<br />

genuine understanding <strong>of</strong> its specific essence. The overintellectual<br />

focus <strong>of</strong> these approaches has detached<br />

architectural discourse from its experiential, embodied and<br />

emotive ground – intellectualisation has pushed aside the<br />

common sense <strong>of</strong> architecture. The interpretation <strong>of</strong><br />

architecture as a system <strong>of</strong> language, for example, with given<br />

operational rules and meanings, gave support to the heresy <strong>of</strong><br />

Postmodernist architecture. The view <strong>of</strong> architectural theory<br />

as a prescriptive or instrumental precondition for design<br />

should be regarded altogether with suspicion. I, for one, seek<br />

a dialectical tension and interaction between theory and<br />

design practice instead <strong>of</strong> a causal interdependence.<br />

The sheer complexity <strong>of</strong> any architectural task calls for an<br />

embodied manner <strong>of</strong> working and a total introjection – to use<br />

a psychoanalytical notion – <strong>of</strong> the task. The real architect<br />

works through his or her entire personality instead <strong>of</strong><br />

manipulating pieces <strong>of</strong> pre-existing knowledge or verbal<br />

rationalisations. An architectural or artistic task is<br />

encountered rather than intellectually resolved. In fact, in<br />

genuine creative work, knowledge and prior experience has to<br />

be forgotten. The great Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida – an<br />

artist who illustrated Martin Heidegger’s book Die Kunst und<br />

der Raum (1969), by the way – once said to me in conversation:<br />

‘I have never had any use for things I have known before I<br />

start my work.’ 6 Joseph Brodsky, the Nobel poet, shares this<br />

view in saying: ‘In reality (in art and, I would think, science)<br />

experience and the accompanying expertise are the maker’s<br />

worst enemies.’ 7<br />

<strong>Architecture</strong> as a Pure Rationality<br />

The seminal artistic question <strong>of</strong> the past decades has been<br />

‘What is art?’ The general orientation <strong>of</strong> the arts since the<br />

late 1960s has been to be increasingly entangled, in fact<br />

identified, with their own theories. The task <strong>of</strong> architecture<br />

has also become a concern since the late 1960s, first through<br />

the leftist critique, which saw architecture primarily as an<br />

unjust use <strong>of</strong> power, redistribution <strong>of</strong> resources and social<br />

manipulation. The present condition <strong>of</strong> excessive<br />

intellectualisation reflects the collapse <strong>of</strong> the social role <strong>of</strong><br />

architecture and the escalation <strong>of</strong> complexities and<br />

frustrations in design practice. The current uncertainties<br />

concern the very social and human role <strong>of</strong> architecture as<br />

well as its boundaries as an art form.<br />

With these observations an opposition emerges: architecture<br />

as a subconscious and direct projection <strong>of</strong> the architect’s<br />

personality and existential experience, on the one hand, and as<br />

an application <strong>of</strong> disciplinary knowledge on the other. This is<br />

also the inherent dualism <strong>of</strong> architectural education.<br />

Science and Art<br />

The relation between scientific and artistic knowledge, or<br />

instrumental knowledge and existential wisdom, requires<br />

some consideration in this survey. The scholarly and literary<br />

work <strong>of</strong> the unorthodox French philosopher Gaston<br />

Bachelard, who has been known to the architectural<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ession since his influential book The Poetics <strong>of</strong> Space was<br />

first published in French in 1958, mediates between the<br />

worlds <strong>of</strong> scientific and artistic thinking. Through<br />

penetrating philosophical studies <strong>of</strong> the ancient elements –<br />

earth, fire, water and air, as well as dreams, daydreams and<br />

imagination – Bachelard suggests that poetic imagination, or<br />

‘poetic chemistry’, 8 as he says, is closely related to<br />

prescientific thinking and an animistic understanding <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world. In The Philosophy <strong>of</strong> No: A Philosophy <strong>of</strong> the New Scientific<br />

Mind, written in 1940 9 during the period when his interest<br />

was shifting from scientific phenomena to poetic imagery<br />

(The Psychoanalysis <strong>of</strong> Fire was published two years earlier),<br />

Bachelard describes the historical development <strong>of</strong> scientific<br />

thought as a set <strong>of</strong> progressively more rationalised<br />

transitions from animism through realism, positivism,<br />

rationalism and complex rationalism to dialectical<br />

rationalism. ‘The philosophical evolution <strong>of</strong> a special piece <strong>of</strong><br />

scientific knowledge is a movement through all these<br />

doctrines in the order indicated,’ he argues. 10<br />

Animated Images<br />

Significantly, Bachelard holds that artistic thinking seems to<br />

proceed in the opposite direction – pursuing<br />

conceptualisations and expression, but passing through the<br />

rational and realist attitudes towards a mythical and<br />

animistic understanding <strong>of</strong> the world. Science and art,<br />

therefore, seem to glide past each other, moving in<br />

opposite directions.<br />

In addition to animating the world, the artistic<br />

imagination seeks imagery able to express the entire<br />

complexity <strong>of</strong> human existential experience through<br />

singular condensed images. This paradoxical task is achieved<br />

through poeticised images, ones that are experienced and<br />

lived rather than rationally understood. Giorgio Morandi´s<br />

tiny still lifes are a stunning example <strong>of</strong> the capacity <strong>of</strong><br />

humble artistic images to become all-encompassing<br />

metaphysical statements. A work <strong>of</strong> art or architecture is not<br />

a symbol that represents or indirectly portrays something<br />

outside itself – it is a real mental image object, a complete<br />

microcosm that places itself directly in our existential<br />

experience and consciousness.<br />

Although I am here underlining the difference between<br />

scientific and artistic inquiry, I do not believe that science and<br />

art are antithetical or hostile to each other. The two modes <strong>of</strong><br />

knowing simply look at the world and human life with<br />

different eyes, foci and aspirations. Stimulating views have<br />

also been written about the similarities <strong>of</strong> the scientific and<br />

the poetic imagination, as well as the significance <strong>of</strong> aesthetic<br />

pleasure and embodiment for both practices.<br />

18

Edward Hopper, Second Storey Sunlight, 1960<br />

Artistic and architectural works are at the same time both specific and universal. Here, the figures and their setting are<br />

fully intertwined. <strong>Landscape</strong>, house and human figures are charged with a sense <strong>of</strong> mystery, drama and anticipation.<br />

The Power <strong>of</strong> Poetic Logic<br />

The logically inconceivable task <strong>of</strong> architecture to integrate<br />

irreconcilable opposites is fundamental and necessary. In<br />

fulfilment <strong>of</strong> this, the essential aims <strong>of</strong> architecture are bound<br />

to be mediation and reconciliation: the essence <strong>of</strong> an<br />

authentic architectural work is the embodiment <strong>of</strong> mediation<br />

and reconciliation. <strong>Architecture</strong> negotiates between differing<br />

categories and oppositions. <strong>Architecture</strong> is conceivable in this<br />

contradictory task only through understanding any design as<br />

a poetic manifestation – poetic imagery is capable <strong>of</strong><br />

overcoming contradictions <strong>of</strong> logic through its polyvalent and<br />

synthetic imagery. As Alvar Aalto once wrote: ‘In every case [<strong>of</strong><br />

creative work] one must achieve the simultaneous solution <strong>of</strong><br />

opposites. … Nearly every design task involves tens, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

hundreds, sometimes thousands <strong>of</strong> different contradictory<br />

elements, which are forced into a functional harmony only by<br />

man’s will. This harmony cannot be achieved by any other<br />

means than those <strong>of</strong> art.’ 11<br />

The <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>of</strong> Painting<br />

Speaking <strong>of</strong> the evolution <strong>of</strong> Modern architecture, Aalto <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

said: ‘But it all began in painting.’ In 1947 he wrote: ‘abstract art<br />

forms have brought impulses to the architecture <strong>of</strong> our time,<br />

although indirectly, but this fact cannot be denied. On the other<br />

hand, architecture has provided sources for abstract art. These<br />

two art forms have alternately influenced each other. There we<br />

are – the arts do have a common root even in our time.’ 12<br />

Painting is close to the realm <strong>of</strong> architecture, particularly<br />

because architectural issues are so <strong>of</strong>ten – or I should say,<br />

unavoidably – part <strong>of</strong> the subject matter <strong>of</strong> painting,<br />

regardless <strong>of</strong> whether we are looking at the representational<br />

or abstract. In fact, this distinction is altogether highly<br />

questionable, because all meaningful art is bound to be<br />

representational in the existential sense.<br />

Late medieval and early Renaissance paintings are<br />

particularly inspiring for an architect because <strong>of</strong> the constant<br />

presence <strong>of</strong> architecture as a subject matter. The early<br />

19

Giovanni Bellini, The Madonna <strong>of</strong> the Meadow, c 1500<br />

<strong>Architecture</strong> and landscape are ‘the constant presence’ in this typical example <strong>of</strong> the Renaissance figure in ‘ground’. The<br />

ground is, however, highly detailed, with minor but ominous traces <strong>of</strong> discordant potential, such as the trees distorted by<br />

the wind, and nearby a watching black rook. The buildings in the rear ground are medieval and defensive rather than<br />

agrarian or even domestic, as one might expect. The innocence and humanity <strong>of</strong> the key figures is nonetheless reassuring.<br />

painters’ interest in architecture seems to be related with the<br />

process <strong>of</strong> the differentiation <strong>of</strong> the world and individual<br />

consciousness, the birth <strong>of</strong> the first personal pronoun ‘I’. The<br />

smallest <strong>of</strong> details suffices to create the experience <strong>of</strong><br />

architectural space: a framed opening or the mere edge <strong>of</strong> a<br />

wall provides an architectural setting. The innocence and<br />

humanity <strong>of</strong> this painterly architecture, the similarity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

human and the architectural figure, is most comforting,<br />

touching and inspiring – this is a truly therapeutic<br />

architecture. The best lessons in domesticity and the essence<br />

<strong>of</strong> home are 17th-century Dutch paintings. In these paintings,<br />

buildings are presented almost as human figures – the<br />

mirrored images <strong>of</strong> the house and the human body were<br />

introduced into modern thought by the psychologist and<br />

analyst CG Jung and have been expressed by countless artists.<br />

I cannot think <strong>of</strong> a more inspiring and illuminating lesson in<br />

architecture than that <strong>of</strong>fered by early Renaissance paintings. If<br />

I could ever design a single building with the tenderness <strong>of</strong><br />

Giotto’s, Fra Angelico’s or Piero della Francesca’s houses, I<br />

would feel that I had reached the very purpose <strong>of</strong> my life.<br />

The interactions between Modern art and Modern<br />

architecture are well known and acknowledged, but I have not<br />

yet seen an architecture inspired by JMW Turner, Claude<br />

Monet, Pierre Bonnard or Marc Rothko, for example. Painting<br />

and other art forms have surveyed dimensions <strong>of</strong> human<br />

emotion and spirit unknown to architects, whose art<br />

conventionally tends to respond to rationalised normality. The<br />

work <strong>of</strong> numerous contemporary artists – Robert Smithson,<br />

Gordon Matta-Clark, Michael Heizer, Donald Judd, Robert Irwin,<br />

Jannis Kounellis, Wolfgang Leib, Ann Hamilton, James Turrell<br />

20

and James Carpenter, among others – is closely related with the<br />

essential issues <strong>of</strong> architecture. These are all artists whose<br />

works have inspired architects and will continue to do so.<br />

We can also study principles <strong>of</strong> artistic thinking and<br />

making in the writings <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong> these artists. Henry Moore,<br />

Richard Serra, Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, James Turrell, all <strong>of</strong><br />

whom write perceptively on their own work, have been<br />

meaningful for me. Artists tend to write more directly and<br />

sincerely <strong>of</strong> their work than architects, who frequently cast an<br />

intellectualised smoke screen across their writings.<br />

The <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>of</strong> Cinema<br />

In its inherent abstractness, music has historically been<br />

regarded as the art form closest to architecture. Cinema is,<br />

however, even closer to architecture than music, not solely<br />

because <strong>of</strong> its temporal and spatial structure, but<br />

fundamentally because both architecture and cinema<br />

articulate lived space. These two art forms create and mediate<br />

comprehensive images <strong>of</strong> life. In the same way that buildings<br />

and cities create and preserve images <strong>of</strong> culture and particular<br />

ways <strong>of</strong> life, cinema projects the cultural archaeology <strong>of</strong> both<br />

the time <strong>of</strong> its making and the era that it depicts. Both forms<br />

<strong>of</strong> art define dimensions and essences <strong>of</strong> existential space –<br />

they both create experiential scenes for life situations.<br />

Film directors create pure poetic architecture, which arises<br />

directly from our shared mental images <strong>of</strong> dwelling and<br />

domesticity as well as the eroticism or fear <strong>of</strong> space. Directors<br />

such as Andrey Tarkovsky and Michelangelo Antonioni have<br />

created a moving architecture <strong>of</strong> memory, longing and<br />

melancholy, one that assures us that the art form <strong>of</strong><br />

architecture is also capable <strong>of</strong> addressing our entire emotional<br />

range, from grief to ecstasy.<br />

Buildings are mental instruments, not simply aestheticised<br />

shelters. The essence <strong>of</strong> architecture is essentially beyond<br />

architecture. The poet Jean Tardieu asks: ‘Let us assume a wall:<br />

what takes place behind it?’ 13 but we architects rarely bother<br />

to imagine what happens behind the walls we have erected.<br />

As we read a poem, we internalise it, and we become the<br />

poem. As Brodsky puts it: ‘A poem, as it were, tells the reader,<br />

“Be like me”.’ 14 When I have read a book and return it back to<br />

its place on the bookshelf, the book, in fact, remains in me. If<br />

it is a great book, it has become part <strong>of</strong> my soul and my body.<br />

The Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal gives a vivid description <strong>of</strong><br />

this act <strong>of</strong> reading: ‘When I read, I don’t really read; I pop a<br />

beautiful sentence in my mouth and suck it like a fruit drop<br />

or I sip it like a liqueur until the thought dissolves in me like<br />

alcohol, infusing my brain and heart and coursing on through<br />

the veins to the root <strong>of</strong> each blood vessel.’ 15 In the same way,<br />

paintings, films and buildings become part <strong>of</strong> us. Artistic<br />

works originate in the body <strong>of</strong> the maker and they return<br />

back to the human body as they are being experienced.<br />

The Dualistic Essence <strong>of</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong><br />

My response to the question <strong>of</strong> whether architecture is or is<br />

not an art form is determined: architecture is an artistic<br />

expression and it is not an art, simultaneously. <strong>Architecture</strong> is<br />

an art in its essence as a spatial and material metaphor <strong>of</strong><br />

human existence, but it is not an art form in its second<br />

nature as an instrumental artefact <strong>of</strong> utility and rationality.<br />

This duality is the very essence <strong>of</strong> the art <strong>of</strong> architecture. This<br />

dual existence takes place on two separate levels <strong>of</strong><br />

consciousness, or aspiration, in the same way that any artistic<br />

work has its existence simultaneously as a material,<br />

disciplinary and concrete execution, on the one hand, and as a<br />

spiritual, unconsciously conceived and perceived imagery,<br />

which carries us to the world <strong>of</strong> dreams, desire and fear, on<br />

the other. <strong>Architecture</strong> can be understood only through this<br />

very duality. ‘A painter can paint square wheels on a cannon<br />

to express the futility <strong>of</strong> war. A sculptor can carve the same<br />

square wheels. But an architect must use round wheels,’ as<br />

Louis Kahn once said. 16<br />

Ontological Ground<br />

The art form <strong>of</strong> architecture is born from the purposeful<br />

confrontation and occupation <strong>of</strong> space. It begins by the act <strong>of</strong><br />

naming the nameless and through perceiving formless space<br />

as a distinct figure and specific place. I wish to emphasise the<br />

adjective ‘purposeful’ – utilitarian purposefulness is a<br />

constitutive condition <strong>of</strong> architecture. The task <strong>of</strong><br />

architecture, however, lies as much in the need for<br />

metaphysical grounding for human thought and experience<br />

as the provision <strong>of</strong> shelter from a raging storm.<br />

<strong>Architecture</strong> as Collaboration<br />

<strong>Architecture</strong>, as with all artistic work, is essentially the<br />

product <strong>of</strong> collaboration. Collaboration occurs in the obvious<br />

and practical sense <strong>of</strong> the word, such as in the interaction<br />

with numerous pr<strong>of</strong>essionals, workmen and craftsmen, but<br />

collaboration occurs as well with other artists, architects and<br />

Andrey Tarkovsky, ‘Mirror’ (film still), 1975<br />

This shows the old family house in which the director had spent much <strong>of</strong> his<br />

youth. To meet the architecture <strong>of</strong> memory accurately, Tarkovsky had the<br />

house painstakingly reconstructed (it had been destroyed by fire – another<br />

memory). In his films he sought to address the entire emotional range <strong>of</strong><br />

man, ranging from grief to ecstasy.<br />

21

landscape architects, not only one’s contemporaries and the<br />