Achillea

Achillea

Achillea

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

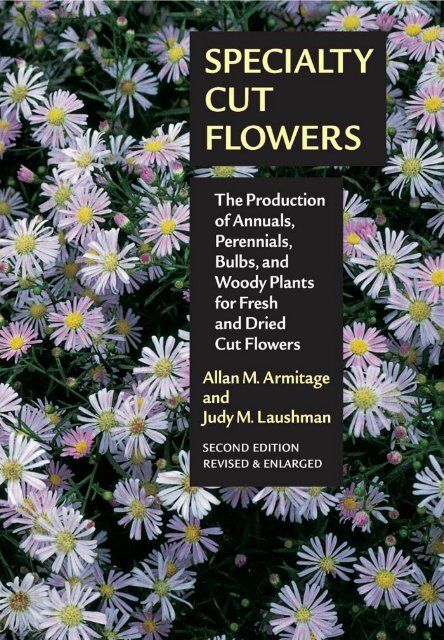

SPECIALTY CUT FLOWERS

SPECIALTY CUT FLOWERS<br />

The Production of Annuals, Perennials, Bulbs, and<br />

Woody Plants for Fresh and Dried Cut Flowers<br />

Second Edition, Revised and Enlarged<br />

Allan M. Armitage and Judy M. Laushman<br />

Illustrations by Patti Dugan<br />

Timber Press<br />

Portland • Cambridge

Photographs by Allan M. Armitage unless otherwise noted.<br />

Frontispiece (Gypsophila paniculata ‘Bristol Fairy’) and all other illustrations by<br />

Patti Dugan<br />

2235 Azalea Drive<br />

Roswell, GA 30075<br />

770.643.8986<br />

email Kdugan3000@aol.com<br />

Copyright © Allan M. Armitage 2003. All rights reserved.<br />

First edition published 1993.<br />

Published in 2003 by<br />

Timber Press, Inc.<br />

The Haseltine Building 2 Station Road<br />

133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450 Swavesey<br />

Portland, Oregon 97204 U.S.A. Cambridge CB4 5QJ, U.K.<br />

Printed in China by Imago<br />

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data<br />

Armitage, A. M. (Allan M.)<br />

Specialty cut flowers : the production of annuals, perennials, bulbs, and<br />

woody plants for fresh and dried cut flowers / Allan M. Armitage and Judy<br />

M. Laushman; illustrations by Patti Dugan.<br />

p. cm.<br />

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).<br />

ISBN 0-88192-579-9<br />

1. Floriculture. 2. Cut flower industry. 3. Cut flowers. 4. Cut flowers—<br />

Postharvest technology. 5. Floriculture—United States. 6. Cut flower<br />

industry—United States. I. Laushman, Judy M. II. Title.<br />

SB405 .A68 2003<br />

635.9'66—dc21<br />

2002073256

To my wife, Susan, who constantly strives for perfection in<br />

everything she attempts. She is my role model.<br />

—A.M.A.<br />

In memory of my mom, Catherine Brennan Marriott; and<br />

with gratitude and love to Roger, Dan, and Katie for their<br />

support, patience, and unique humor.<br />

—J.M.L.

This page intentionally left blank

CONTENTS<br />

Preface 9<br />

Acknowledgments 12<br />

Introduction 15<br />

Postharvest Care 20<br />

Drying and Preserving 30<br />

Cut Flowers: <strong>Achillea</strong> to Zinnia 35<br />

References 553<br />

Appendix I. Stage of Harvest 559<br />

Appendix II. Additional Plants Suitable for Cut Flower Production 565<br />

Appendix III. Useful Conversions 571<br />

U.S. Department of Agriculture Hardiness Zone Map 572<br />

Index of Botanical Names 573<br />

Index of Common Names 581<br />

Color photographs follow page 64<br />

7

This page intentionally left blank

PREFACE<br />

The first edition of Specialty Cut Flowers arrived on book stands in 1993 and<br />

immediately became a highly popular book on the subject. A good deal has<br />

changed since the first edition, including the emergence of additional crops in<br />

the cut flower market and the decline of others. The world has seen new leaders,<br />

breakthroughs in medicine and science, boom and bust of economic indicators,<br />

conflicts, peace, and unimagined visions of terrorism. Through all these events,<br />

people went about their business. Companies emerged and others failed, money<br />

was made and life savings were lost. The cut flower business was no exception.<br />

Florida and California are home to major flower farms, and a scattering of<br />

farms greater than 50 acres can be found in various other states; but large growing<br />

facilities are mainly found overseas. The dominance of the overseas grower<br />

has had an interesting effect on the cut flower market in America. Certainly,<br />

American growers cannot compete in the rose, carnation, and mum markets,<br />

nor are staples like baby’s breath easy to grow profitably. These flowers are such<br />

commodity items, it is difficult to be profitable, regardless of where or how these<br />

plants are grown. But while the bulk of flowers still arrives from overseas, American<br />

growers have filled in many of the gaps because they are able to serve small<br />

markets and to capitalize on the issues of freshness and diversity of material.<br />

Markets are always changing, but as long as the consumer wants the product,<br />

there are enough outlets for everyone.<br />

The marketing of flowers has changed. The traditional route of grower to<br />

wholesaler to retailer continues to be the highway for large numbers of cut<br />

stems; however, smaller and equally efficient avenues have reemerged. The small<br />

grower has made a huge comeback, supporting farmers’ markets in many small<br />

towns and large cities.<br />

When the first edition was written, specialty cut flowers were just beginning<br />

to be recognized as “real” crops, not just flunkies of the Big 3—roses, carnations,<br />

and mums. Today, the trend toward specialty crops is even stronger because of<br />

the willingness of the market to try unusual material and the willingness of<br />

growers to provide it. For example, marginal crops like verbena and cardoon are<br />

found as cut stems; florists are offering dodecatheon, Chinese forget-me-nots,<br />

and weed-like plants like chenopodium, atriplex, and even Johnson grass. And<br />

who would have thought that vegetables like okra, artichoke, ornamental kale,<br />

9

10 PREFACE<br />

and eggplant would be considered useful crops for cut stems? But growers are<br />

producing them, and they are being sold. One thing is certain about the cut<br />

flower market: the only limitation to what can be used as a cut stem is the imagination<br />

of the user.<br />

The consumer remains the key. The cut flower market is like a burlap bag full<br />

of puppies: the edges are always moving, it constantly changes position, and it is<br />

not made up of a single predictable element but rather of many elements, moving<br />

randomly. Nobody can predict what the strength of the market will be,<br />

nobody can predict the next great flower or the next great color. The question<br />

remains, how do we keep the consumer interested in our product? It really<br />

doesn’t matter if the stems come from Bogota, Quito, or Omaha, what matters<br />

is that someone wants to buy flowers. Promotional campaigns, television ads,<br />

Grandmother’s Day all help—but what keeps everyday consumers and professional<br />

floral arrangers coming back is the perception of value. Most producers<br />

don’t have the funds to create ad campaigns, and to be honest, who pays attention<br />

to ads anymore? No amount of advertising is going to talk anyone into a<br />

bouquet or some stems if they don’t believe that those flowers push an emotional<br />

button, such as love, beauty, sympathy, or gratitude. These buttons are<br />

genetically programmed in the human race; the only difference is what pushes<br />

them. Fine food, fine wine, and good movies all compete for these spots in a person’s<br />

soul, so what is a cut flower farmer in Dubuque to do? The answer is<br />

uncomplicated: grow fine flowers—not just flowers, but fine flowers. Provide the<br />

best freshness, the best stems, the best bouquets, and the best service you know<br />

how, and service those buttons. That is all you can do, but if that is done well, the<br />

rest takes care of itself.<br />

The answer might be simple, but the techniques needed to grow fine flowers<br />

and provide fine service are constantly changing. Production methods, cultivar<br />

selection, postharvest procedures, transportation, floral displays, and running<br />

the day-to-day aspects of a business are challenging and tiring. To be successful,<br />

one must be a horticulturist, agronomist, and pathologist, mixed with the skills<br />

of a salesperson and truck driver, and topped off with the enthusiasm of a cheerleader.<br />

Larger operations can delegate these activities; smaller ones find a few<br />

people balancing them all.<br />

This edition serves the same function as the first—to help growers produce the<br />

fine flowers needed to be profitable. But some changes are obvious. Two authors<br />

are better than one, and the addition of Judy Laushman as co-author has elevated<br />

the quality of the book significantly. The format has been changed for easier<br />

reference (bulb or woody, plants now appear in single, straightforward A-to-<br />

Z order), crops have been added, and research findings and readings have been<br />

updated (so you know we didn’t just make all this stuff up). We debated long and<br />

hard over the addition of several flowers. We know they’re being grown, sold,<br />

and accepted by the market; however, unless we could find current research as<br />

well as sufficient production information, we decided that crop would have to<br />

wait until the next edition.<br />

But the most important change has been the input of the cut flower growers<br />

themselves, the vast majority of whom are members of the Association of Spe-

PREFACE 11<br />

cialty Cut Flower Growers. They not only reviewed the sections, they gave us permission<br />

to use their candid comments about their experiences in growing the<br />

crops. These personal, “real world” comments provide invaluable insights and<br />

are a refreshing contrast to the many impersonal words and numbers in the<br />

book. To everyone who helped, you have the thanks of every reader, in every state<br />

and country.<br />

Allan M. Armitage<br />

Judy M. Laushman

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

The information contained in a book of this magnitude is only as good as the<br />

people who helped generate it. We were extraordinarily fortunate to have had the<br />

help of several talented reviewers. They read, corrected, critiqued, and suggested<br />

changes to various sections; their comments and suggestions were invaluable.<br />

Many of the people below assisted in the first edition (1993), and affiliations<br />

and locations may have changed since that time.<br />

Carolyne Anderson, Anderson Farms, Clark, Mo.<br />

Bob Anderson, Dept. of Horticulture, University of Kentucky, Lexington<br />

Kelly Anderson, WildThang Farms, Ashland, Mo.<br />

Frank Arnosky, Texas Specialty Cut Flowers, Blanco, Tex.<br />

Linda Baranowski-Smith, Blue Clay Plantation, Oregon, Ohio.<br />

J. B. Barzo-Reinke, Small Pleasures Farm, Bandon, Ore.<br />

Bill Borchard, PanAmerican Seed Company, Santa Paula, Calif.<br />

Pat Bowman, Cape May Cut Flowers, Cape May, N.J.<br />

Jo Brownold, California Everlastings, Dunnigan, Calif.<br />

Lynn Byczynski, Growing for Market, Lawrence, Kans.<br />

Maureen Charde, High Meadow Flower Farm, Warwick, N.Y.<br />

Phillip Clark, Endless Summer Flower Farm, Camden, Maine<br />

Ken and Suzy Cook, Atlanta, Ga.<br />

Douglas Cox, Dept. of Horticulture, University of Massachusetts, Amherst<br />

Ralph Cramer, Cramers’ Posie Patch, Elizabethtown, Pa.<br />

Mimo Davis, WildThang Farms, Ashland, Mo.<br />

Elizabeth Dean, Wilkerson Mill Gardens, Palmetto, Ga.<br />

August De Hertogh, Raleigh, N.C.<br />

John Dole, Dept. of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State University,<br />

Raleigh<br />

Dave Dowling, Farmhouse Flowers, Brookeville, Md.<br />

Fran Foley, Aptos, Calif.<br />

Janet Foss, J. Foss Garden Flowers, Everett, Wash.<br />

Keith Funnell, Dept. of Horticulture, Massey University, Palmerston North,<br />

New Zealand<br />

Jim Garner, Atlanta, Ga.<br />

12

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 13<br />

Karen Gast, Kansas State University, Manhattan<br />

Chas Gill, Kennebec Flower Farm, Bowdoinham, Maine<br />

Ken Goldsberry, Dept. of Horticulture, Colorado State University, Fort<br />

Collins<br />

Jack Graham, Dramm and Echter, Watsonville, Calif.<br />

Bernadette Hammelman, Hammelman’s Dried Floral, Mt. Angel, Ore.<br />

Jeff Hartenfeld, Hart Farm, Solsberry, Ind.<br />

Will Healy, Ball Seed Company, West Chicago, Ill.<br />

Brent Heath, The Daffodil Mart, Gloucester, Va.<br />

Mel Heath, Bridge Farm Nursery, Cockeysville, Md.<br />

Peter Hicklenton, Agriculture Canada, Kentville, Nova Scotia<br />

Christy Holstead-Klink, Floral Communication and Technical Services,<br />

Nazareth, Pa.<br />

Mark Hommes, Bulbmark, Inc., Wilmington, N.C.<br />

Steve Houck, Accent Gardens, Boulder, Colo.<br />

Cathy Itz, McCall Creek Farms, Blanco, Tex.<br />

Jennifer Judson-Harms, Cricket Park Gardens, New Hampton, Iowa<br />

Corky Kane, Germania Seed Company, Chicago, Ill.<br />

Philip Katz, PanAmerican Seed Company, Santa Paula, Calif.<br />

John Kelley, Dept. of Horticulture, Clemson University, Clemson, S.C.<br />

Huey Kinzie, Stoney Point Flowers, Gays Mills, Wis.<br />

Roy Klehm, Klehm Nursery, South Barrington, Ill.<br />

Mark Koch, Robert Koch Industries, Bennett, Colo.<br />

Bob Koenders, The Backyard Bouquet, Armada, Mich.<br />

Ginny Kristl, Johnny’s Selected Seeds, Albion, Maine<br />

John LaSalle, LaSalle Florists, Whately, Mass.<br />

Dave Lines, Dave Lines’ Cut Flowers, La Plata, Md.<br />

Dale Lovejoy, Anderson Levitch/Lovejoy Farms, Eltopia, Wash.<br />

Howard Lubbers, Ottawa Glad Growers, Holland, Mich.<br />

Tom Lukens, Golden State Bulb Growers, Watsonville, Calif.<br />

Robert Lyons, Dept. of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State<br />

University, Raleigh<br />

Roxanne McCoy, Lilies of the Field, West Falls, N.Y.<br />

Shelley McGeathy, McGeathy Farms, Hemlock, Mich.<br />

Jeff McGrew, Jeff McGrew Horticultural Products, Mt. Vernon, Wa.<br />

Mike Mellano Sr., Mellano & Company, San Luis Rey, Calif.<br />

Ruth Merrett, Merrett Farm, Upper Kingsclear, N.B.<br />

Kent Miles, Botanicals by K&V, Seymour, Ill.<br />

Susan Minnich, Coles Brook Farm, Becket, Mass.<br />

Don Mitchell, Flora Pacifica, Brookings, Ore.<br />

Brian Myrland, Floral Program Management, Middleton, Wis.<br />

Sally Nakasawa, Nakasawa Everlastings, Yuma, Ariz.<br />

Jim Nau, Ball Seed Company, West Chicago, Ill.<br />

Knud Nielsen III, Knud Nielsen Company, Evergreen, Ala.<br />

Peter Nissen, Sunshine State Carnations, Hobe Sound, Fla.<br />

Leonard Perry, Dept. of Horticulture, University of Vermont, Burlington

14 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

Ed Pincus, Third Branch Flower, Roxbury, Vt.<br />

Bob Pollioni, Ventura, Calif.<br />

Bill Preston, Bill Preston Cut Flowers, Glenn Dale, Md.<br />

Whiting Preston, Manatee Fruit Company, Palmetto, Fla.<br />

Jeroen Ravensbergen, PanAmerican Seed Company, The Netherlands<br />

Jim Rider, Jim Rider Flowers, Watsonville, Calif.<br />

Jan Roozen, Choice Bulb Farm, Mount Vernon, Wash.<br />

Roy Sachs, Flowers and Greens, Davis, Calif.<br />

Paul Sansone, Here and Now Garden, Gales Creek, Ore.<br />

Craig Schaafsma, Kankakee Valley Flowers, St. Anne, Ill.<br />

Bev Schaeffer, Schaeffer Flowers, Conestoga, Pa.<br />

Ray Schreiner, Schreiner’s Iris Gardens, Salem, Ore.<br />

Mary Ellen Schultz, Northbloom Farm, Belgrade, Mont.<br />

Gay Smith, Pokon & Chrysal, Portland, Ore.<br />

Ron Smith, R. Smith Farm, Renfrew, Pa.<br />

Roy Snow, United Flower Growers, Burnaby, B.C.<br />

George Staby, Perishables Research Organization, Grafton, Calif.<br />

Vicki Stamback, Bear Creek Farm, Stillwater, Okla.<br />

Rudolf Sterkel, Ernst Benary of America, Sycamore, Ill.<br />

Dennis Stimart, Dept. of Horticulture, University of Wisconsin, Madison<br />

Mindy Storm, Blairsville, Ga.<br />

Joan Thorndike, Le Mera Gardens, Ashland, Ore.<br />

Ralph Thurston, Bindweed Farm, Blackfoot, Idaho<br />

Ann Trimble, Trimble Field Flowers, Princeton, Ky.<br />

Bernie Van Essendelft, Dual Venture Farm, Pantego, N.C.<br />

Kate van Ummersen, Sterling Flowers, Brooks, Ore.<br />

Alice Vigliani, Maple Ridge Peony Farm, Conway, Mass.<br />

Mike Wallace, Wood Creek Farm, Cygnet, Ohio<br />

Ian Warrington, HortResearch, Palmerston North, New Zealand<br />

Van Weldon, Wood Duck Farm, Cleveland, Tex.<br />

Eddie Welsh, Palmerston North, New Zealand<br />

Linda White-Mays, Sundance Nursery and Flowers, Irvine, Ky.<br />

Roxana Whitt, Wise Acres, Huntingtown, Md.<br />

Tom Wikstrom, Happy Trowels Farm, Ogden, Utah<br />

Blair Winner, PanAmerican Seed Company, Santa Paula, Calif.<br />

Bob Wollam, Wollam Gardens, Jeffersonton, Va.<br />

Jack Zonneveld, M. van Waveren Co., Mt. Airy, N.C.<br />

Patrick Zweifel, Oregon Coastal Flowers & Bulbs, Tillamook, Ore.

INTRODUCTION<br />

In the first edition of this book, the term “specialty cut flower” was defined as any<br />

crop other than roses, carnations, and chrysanthemums. In the years since, the<br />

market has changed so much, and the diversity of flowers in the market has<br />

become so great, that the term “specialty” really means very little any more. Bob<br />

Wollam, president of the Association of Specialty Cut Flower Growers, Inc.<br />

(2002–03), defines a specialty cut as “something that isn’t on the market on a regular<br />

basis or is there only for an exceptionally short time period. It can’t be used<br />

in a numbered bouquet, like FTD #46, which requires flowers you can get all<br />

year round.” John Dole of North Carolina State University adds that the definition<br />

is continuously evolving: “Soon . . . we will simply refer to ‘cut flower’ production<br />

in the U.S., not ‘specialty’ cut flower [production].”<br />

However, the Big 3 traditional crops have historically comprised the largest<br />

portion of cut flower production and sales in the world market and, in all likelihood,<br />

will continue to do so. The unwieldy number of specialty species, the<br />

difficulty in controlling field conditions, the lack of standards for specialty cuts,<br />

and the popularity of greenhouse-grown flowers made traditional crops easier to<br />

fund, and information flowed readily. The business of growing specialty cut<br />

flower crops, however, has been practiced for hundreds of years. European and<br />

Asian growers produced a vast variety of cut flowers in fields and conservatories.<br />

The American grower joined in with large acreages of peonies, tuberose,<br />

larkspur, gypsophila, and gladiolus, especially during the 1940s and 1950s.<br />

Growers come and go, the world market rises and falls, and while consumption<br />

of cut flowers has been stagnant in recent years, there is still significant room for<br />

expansion.<br />

The type of floral product purchased and the amount of money spent is more<br />

dependent on the use for which it is intended than on the product itself. In America,<br />

the most important reason is to celebrate special occasions: anniversaries,<br />

birthdays, Valentine’s Day, funerals, weddings. Competition for the special-occasion<br />

dollar is fierce. Flowers must go neck-and-neck against restaurants, movies,<br />

theaters, chocolates, and gifts. A second reason is to express emotions, such as<br />

love, thanks, condolence, apology, and congratulations. The third and still<br />

untapped reason for purchasing cut flowers is to create a pleasant atmosphere at<br />

home and work; promoting the use of flowers in these everyday ways must<br />

15

16 INTRODUCTION<br />

increase if they are to become a mainstream item. Whatever the consumer’s<br />

impulse to buy, enhanced sales can be accomplished only through production of<br />

high-quality flowers, aggressive promotion, and an increased number of outlets.<br />

The Role of Imports<br />

In some overseas countries, cut flowers have been politically expedient, and their<br />

development has been aggressively supported. Standard flowers—roses, carnations,<br />

mums, gypsophila, gladiolus—arrive from offshore suppliers daily, and,<br />

although many may disagree, their presence has had a positive influence on the<br />

American grower. The marketing skills of the Dutch, the inexpensive stems from<br />

Colombia and Ecuador, and the acceptance of these crops by the American florist<br />

have resulted in more crops and a significantly higher volume of cut flowers<br />

sold in this country than ever before. Competition from abroad will no doubt<br />

increase for all species of cut flowers, yet American growers will adjust and use<br />

that competition to their advantage. Some buyers will always base their purchases<br />

solely on price, but what else is new?<br />

The question, then, begs to be asked. How can the American grower compete?<br />

He can best compete by growing the highest quality product possible, providing<br />

the best service available, and ensuring proper handling and harvesting<br />

methods at a reasonable price. Local growers can supply specific products that<br />

ship poorly or that can be produced efficiently in their area. In fact, growers must<br />

always look for local niches for flowers that are poor shippers and otherwise<br />

difficult to find. Quality, freshness, and consistency are the keys to competitiveness,<br />

whether one is competing with Holland or California. Domestic growers<br />

must provide fresh-dated flowers and guarantee on-time delivery of all flowers<br />

on the contract. If flowers are going to be supplied by overseas growers, make<br />

those growers earn every dollar. The American grower can waste his time looking<br />

over his shoulder, or spend it doing a better job providing a consistently<br />

high-quality fresh-dated crop, on time and for a realistic price.<br />

Product Mix<br />

Many species are useful as cut flowers, but the decision of what to grow must be<br />

based on climatic conditions, availability of seed and plants, and, most important,<br />

what will sell in a given area. Diversity of product is important; growers<br />

should always be on the lookout for something new, and the importance of staying<br />

up-to-date cannot be overstated. But just remember: it is impossible to grow<br />

everything, and it is easy to turn around and suddenly find oneself producing<br />

100 different species and cultivars.<br />

More than ever before, the consumer reacts to and is willing to pay for the<br />

unusual. It used to be that the buying public was unaware of many lesser-grown<br />

plants, but times have changed, and the lesser-known specialty crops are in high<br />

demand. With the emergence of better cultivars and aggressive marketing,<br />

obscure species may turn out to be major winners. Growers of specialty flowers<br />

should not believe their products will replace the rose, or even the carnation; to

INTRODUCTION 17<br />

believe so is unrealistic and self-defeating. Growers, wholesalers, and retailers<br />

should be striving, instead, to complement the rose, enhance the carnation,<br />

show off the mum, and liven up the gladiolus.<br />

Plant Diversity<br />

The diversity of available plants and seeds includes annuals, perennials, bulbs,<br />

and woody species. Each class of cut flowers (or berries, foliage, stems) includes<br />

a wealth of plant species and cultivars, which may be used throughout the growing<br />

season. All these stems are now seen in wholesale coolers, florist outlets, and<br />

garden shops. Such species may end up routed through auctions or local flower<br />

or farmers’ markets, or sold directly to florists. Personal contacts between growers<br />

and salespersons can be made and sustained if there is a will to do so. Nowhere<br />

is it written that all produce must go through a distributor, ending up as<br />

generic product in a generic market for faceless people.<br />

A movement toward cut flowers grown for the local market has taken place,<br />

and consumers shopping at local florists and farmers’ markets are benefitting<br />

the most from this return to hometown roots. No longer is it necessary to ship<br />

a majority of flowers long distances before selling them. Growing areas near<br />

small towns and large cities have been established to provide material for distribution<br />

to those areas. There is no reason why growers near New York or Chicago<br />

or Denver should not be efficient enough to supply their own areas with<br />

product first, supplemented with materials from distant fields and lands.<br />

Volume and Price<br />

The volume of material in the market directly affects its price, creating a trap<br />

that many growers fall into. A new grower, for example, may find the demand for<br />

his crop is higher than expected, so immediately doubles production. More than<br />

likely, such a decision will prove unprofitable. Simply because 2000 bunches of<br />

flowers sold for $5 a bunch does not mean that 4000 bunches will sell for the<br />

same price. Not only does the unit price for his product fall, so do prices for<br />

other growers of the same product. The classic grower thinking that more is better<br />

must be changed. Similarly, the price a grower demands for a crop should not<br />

automatically fall in times of market glut. If the quality is consistent throughout<br />

the year, the grower need not acquiesce to claims of cheaper sources by the buyer.<br />

If trust and consistency of quality have been cultivated with the buyer, discounting<br />

the product to the point where profit has disappeared is poor business.<br />

Sometimes it is better not to harvest the excess than to sell it for a loss. No<br />

one wants to throw away potential earnings; however, once prices are lowered, it<br />

is difficult to raise them once again.<br />

Grading<br />

Most specialty cut flowers in America are not graded. The lack of standards<br />

reflects the inability to adequately enforce them in a country with such diverse

18 INTRODUCTION<br />

market outlets. Specific crops may call for specific standards, and it would seem<br />

to make sense to establish minimum baseline standards for appearance and<br />

quality of all American crops. Until such time as standards are agreed upon,<br />

grading will continue to be the domain of the producer—which is not all bad.<br />

Good businesses will become known not only for the quality of their product but<br />

for the consistency of their grading. Strict grading enhances trust: the buyer will<br />

soon realize that bunch after bunch, box after box, week after week, the product<br />

is consistent and true to grade.<br />

One’s grading system should be based on a combination of flower quality,<br />

stem strength, and stem length—standards that once established must be<br />

adhered to throughout the growing season. The numbers of flowers in a bunch<br />

should be established and maintained. For most flowers, a minimum of 10 stems<br />

per bunch is the standard. Let’s keep it simple: people know how to count by<br />

10s, while 8, 12, or 15 stems per bunch simply confuses the issue. Obviously,<br />

some larger flowers will not be bunched in 10s, and filler-type products are often<br />

sold by weight. Simply because stems are fatter or flowers a little larger does not<br />

excuse bunches with fewer stems. Similarly, if stems are thin, adding more flowers<br />

to the bunch does not raise the quality of the flowers—they still have thin<br />

stems! Placing poor-quality stems in the middle of a bunch or at the bottom of<br />

the box fools no one. Such tactics eventually fail, and someone gets hurt. Flowers<br />

must be graded as if the grower were the buyer, not the seller.<br />

Consignment<br />

Let the system of consignment die; it is wasteful and unproductive, benefiting no<br />

one in the long run. The product should be bought, not rented from the grower,<br />

and the responsibility for final sale and distribution of the fresh product must<br />

rest with the florist, distributor, or wholesaler, not the producer. Consignment<br />

systems inevitably result in ill will between producer and distributor and tend to<br />

weigh down a distribution system already burdened with lingering mistrust.<br />

Trust<br />

Trust between wholesaler and producer is a necessity in any business transaction.<br />

This will never change. In a good working relationship, problems on either<br />

the producer’s or wholesaler’s part can be discussed and corrected in professional<br />

terms. An open and frank communication makes the business of cut flowers<br />

far more enjoyable for all concerned. Similarly, discussion between growers<br />

is essential if the cut flower industry is to blossom and succeed in this country.<br />

People who put on cloaks of secrecy and refuse to share experiences and methods<br />

with others do themselves a great disservice. We have enough problems—<br />

seasonality, imports, hail, rain, freezing temperatures, drought, heat, and rodents—without<br />

tripping over each other to keep “secrets” secure. A free-flowing<br />

exchange of ideas is essential in any business, and this one is no exception.<br />

To that end, membership in trade associations, such as those that follow, is<br />

highly recommended for anyone dealing with specialty cut flowers.

Association of Specialty Cut Flower Growers, Inc.<br />

MPO Box 268<br />

Oberlin, OH 44074-0268<br />

phone 440.774.2887<br />

fax 440.774.2435<br />

www.ascfg.org<br />

International Cut Flower Growers<br />

P.O. Box 99<br />

Haslett, MI 48840<br />

phone 517.655.3726<br />

fax 517.655.3727<br />

ICFG@voyager.net<br />

Preserved Floral Products Association<br />

2287 Ash Point Road<br />

White Cloud, KS 66094<br />

phone 785.595.3327<br />

fax 785.595.3283<br />

Society of American Florists<br />

1601 Duke Street<br />

Alexandria, VA 22314<br />

phone 800.336.4743<br />

www.safnow.org<br />

INTRODUCTION 19<br />

The Association of Specialty Cut Flower Growers (ASCFG) is the only group<br />

devoted solely to the business of specialty cut flowers; their electronic bulletin<br />

board, on which members air problems and discuss solutions, is particularly<br />

effective.

POSTHARVEST CARE<br />

Whether flowers are delivered in a Volkswagen bus to the farmers’ market down<br />

the road or shipped thousands of miles across the world, comprehensive postharvest<br />

care and handling are essential. It may be argued that no one step in the<br />

chain of marketing flowers to the consumer is more important than any other.<br />

That is, if even one step is poorly accomplished, the whole chain is weakened: if<br />

water quality is poor, the fertility program is out of balance; if the incorrect cultivar<br />

is grown, the quality and potential sales of the crop suffer. These comments<br />

are true; however, once the stem is cut, proper harvesting, handling, and postharvest<br />

treatments are essential for maintaining the quality of the flowers. Without<br />

a suitable postharvest program, the wholesaler, florist, or consumer is being<br />

sold a defective item.<br />

The grower is responsible for the first stage of postharvest treatment, but<br />

others who handle the flowers (wholesaler, trucker, florist) have equal responsibility.<br />

It is easy to understand the importance of postharvest techniques when<br />

flowers must be shipped a long distance, but perhaps not so easy to justify the<br />

expense and trouble when they are only going across town. That thinking gets<br />

everyone in trouble. A lack of a consistent postharvest program can limit the<br />

sale of fresh flowers and greens. Consumers feel cheated when the flowers they<br />

purchase decline prematurely. The perception of “not getting one’s money’s<br />

worth” is extremely dangerous to this industry and must be eliminated.<br />

Carnations and chrysanthemums are popular because, in addition to shipping<br />

well, florists and the public perceive they are a good value for the money.<br />

That perception is the key to success in the fresh cut flower industry. Message to American<br />

growers: if your flowers are not fresher, of better quality, and longer lasting than<br />

those from overseas, then you should think seriously about another line of work.<br />

We need to sell more flowers, period. Better postharvest care translates into<br />

more flowers being sold, regardless of origin. More flowers sold translates to<br />

higher public visibility and a perceived necessity of the product. Purchasing<br />

flowers should be as commonplace as renting a video or dining out, but this<br />

won’t happen until the value for the money spent is perceived to be at least equal<br />

to that movie or meal. The industry must not only believe in the importance of<br />

correct postharvest treatments but practice them as well, for if flowers are not<br />

well handled, the future of the cut flower grower is questionable.<br />

20

Considerations of the Crop in the Field<br />

POSTHARVEST CARE 21<br />

Steps to enhance postharvest longevity of the flower may be taken before any<br />

flowers are cut. These practices begin with the selection of the cultivar to be<br />

grown and extend to maintaining the health of the plant in the field.<br />

Species and cultivar selection: Proper cultivar selection can mean the difference<br />

between profitability and economic struggle. Choose cultivars not only for<br />

flower color but for their potential vase life; simple tabletop tests of old favorites<br />

and new introductions will provide valuable data to help with plant selection.<br />

Test new products in vases and in foam; the more information the buyer receives,<br />

the more he will rely on the grower. Relying on information from the breeder is<br />

useful but should not be the final criterion for selection. Do it yourself.<br />

The environments under which plants will be grown must be considered. If a<br />

crop is grown in an unsuitable area, plants will never be as vigorous and active as<br />

they would be under more hospitable conditions. In general, plants grown in<br />

marginal environments are stunted and produce fewer flowers (each of which<br />

has a shorter vase life) compared to plants grown in a favorable environment.<br />

Why try to grow delphiniums in Phoenix in June? Attempting to grow a crop<br />

unsuitable to the area invariably results in a low-quality product and a decline in<br />

postharvest life.<br />

Health of the plants in the field: Integrating good postharvest methods with a<br />

growing regime that produces reasonable yields and high-quality stems is a goal<br />

to which all growers should aspire. Research has shown that anything that<br />

results in prolonged stress (improper fertility, over- or underabundance of water,<br />

cold, or heat) reduces postharvest life. Healthy plants produce long-lasting flowers,<br />

but it does not necessarily follow that the lushest, most vigorous plants bear<br />

flowers with the best postharvest life. In fact, flowers from plants that have been<br />

heavily fertilized or grown under warm temperatures often exhibit shorter shelf<br />

life than those that are grown a little “leaner” and cooler. In the greenhouse,<br />

plants are often hardened off by reducing temperature, fertilizer, or water prior<br />

to harvest to increase the life of the flower.<br />

Harvesting: The best time to harvest flowers is always a compromise, reached<br />

by weighing various factors. Flowers harvested in the heat of the day can be<br />

stressed by high temperatures. Dark-colored flowers can be as much as 10F (6C)<br />

warmer than white flowers on a bright, hot day. It may be argued that harvesting<br />

should be accomplished in late afternoon because the buildup of food (for<br />

subsequent flower development) from photosynthesis is greater than it is in<br />

the morning, but in the morning, water content of the stem is high and temperatures<br />

are low. These beneficial factors, combined with the practical considerations<br />

of packing, grading, and shipping of the same stems, mean that<br />

stems are generally cut early in the day. Harvesting should be delayed, however,<br />

until plants are dry of dew, rain, or other moisture. Cutting at high temperatures<br />

(above 80F, 27C) and high light intensity should be avoided whenever<br />

possible.<br />

After harvest, transfer all stems immediately to a hydrating solution and then<br />

to a cool storage facility to prevent water loss. Ethylene-sensitive flowers (see list

22 POSTHARVEST CARE<br />

later in this section) should also be placed in a hydrating solution in the field<br />

until treated with silver compounds in the grading area.<br />

Stage of development of the flower: In general, harvesting in the bud stage or as<br />

flowers begin to show color results in better postharvest life for many crops. One<br />

reason for cutting flowers in a tight stage is to reduce space during shipping.<br />

Tight flowers are not as susceptible to mechanical damage or ethylene, and more<br />

stems may be shipped in the box than stems with open flowers. Another is that<br />

tight-cut flowers, if handled well, provide more vase life to the consumer. But the<br />

tight flower stage is not optimum for all flowers; spike-like flowers, such as<br />

aconitum, delphiniums, and physostegia, should have 1 or 2 basal flowers open,<br />

while yarrow and other members of the daisy family require that flowers be fully<br />

open prior to harvest. If one is not shipping long distances, harvesting during the<br />

tight stage is not necessary; if you’re displaying your flowers at a farmers’ market,<br />

give your customers some color to view. In general, if flowers are cut tight, placing<br />

stems in a bud-opening solution is useful for the secondary user (wholesaler,<br />

florist, consumer). Research has not been conducted for every specialty cut<br />

flower, but the optimum harvest stage is provided at each entry for all crops discussed<br />

in the book. The optimum stage has been determined by research, observation,<br />

or discussion with growers and wholesalers. Appendix I is a brief summation<br />

of the recommendations.<br />

Considerations of the Cut Stem<br />

Air temperature: No factor affects the life of cut flowers as much as temperature.<br />

At every stage along the cut flower system—after harvest, boxing, shipping,<br />

at the wholesaler and the florist—the cut stems should be wrapped in cold. The<br />

importance of cold is directly related to the length of the journey. Michael Reid,<br />

perhaps the nation’s leading researcher in cut flower postharvest, states emphatically<br />

that the life of most flowers is 3–4 times longer when they’re held at 32F<br />

(0C) than at 50F (10C); some short-lived flowers, such as daffodils, persist 8<br />

times longer (Reid 2000). Even if flowers are hydrated and held and shipped in<br />

water, warm temperatures still result in loss of postharvest quality.<br />

For the producer, growing cut flowers without a cooler is like having a restaurant<br />

without a kitchen. Warm temperatures cause increased water loss, loss of<br />

stored food, and rapid reduction of vase life. Most cut stems should be cooled to<br />

33–35F (1–2C). It is imperative to rapidly reduce field heat and to maintain cool<br />

temperatures throughout the marketing chain of the flowers. If possible, stems<br />

should be graded and packed in the cooler; though this is not particularly popular<br />

with employees, the quality of the flowers is greatly enhanced. If field heat<br />

is not removed, or if loose flowers or flower boxes are simply stacked in a refrigerated<br />

room, rapid deterioration takes place. In rooms without proper air movement,<br />

it can take 2–4 days to cool a stack of packed boxes of warm flowers, and<br />

this same stack will never reach recommended temperatures, even after 3 days in<br />

a refrigerated truck (Holstead-Klink 1992). Proper box design and forced-air<br />

cooling of boxes to quickly remove heat significantly enhance the postharvest<br />

life of flowers.

POSTHARVEST CARE 23<br />

Having said all that, not all cut flowers should be cooled at 33–35F (1–2C);<br />

tropicals such as anthuriums and celosia prefer temperatures above 50F (10C).<br />

Forced-air cooling: Boxes with holes or closeable flaps are necessary for forcedair<br />

cooling, in which air is sucked out of (or blown into) the boxes with an inexpensive<br />

fan. In general, cooling times are calculated as the time to reach 7/8 of<br />

the recommended cool temperature for a particular species; often that temperature<br />

is 40F (4C). Half-cooling time (the time required to reduce the temperature<br />

by 50%) ranges from 10 to 40 minutes (Nell and Reid 2000), depending on product<br />

and packaging. Flowers should be cooled until they are 7/8 cool or about 3<br />

half-cooling times. Work by Rij et al. (1979), an excellent early synopsis of precooling,<br />

provided methods of setting up small forced-air systems and information<br />

for calculating cooling times. Proper packing of the boxes is necessary to<br />

reduce temperature quickly. A minimum of 3" (8 cm) between the ends of the<br />

flowers and the ends of the boxes will prevent petal damage and enhance cold<br />

temperature distribution inside the boxes (Reid 2000).<br />

Initial and final box temperature at the packing shed should be measured<br />

and entered on data sheets. Actual temperatures should be appraised with a<br />

long-probed thermometer; the final temperature of the flowers can be estimated<br />

by using a temperature probe to measure the air being exhausted from the box.<br />

The air coming out of the box will always be cooler than the flowers, and an experienced<br />

operator knows the relation between flower temperature and exhaust<br />

temperature.<br />

The retailer is responsible for maintaining proper temperature control<br />

through to the sale. When the boxes arrive at their final destination, the box<br />

temperature can be again measured with an inexpensive needle-type probe even<br />

before the boxes are opened. If temperature inside the box is above 37F (3C), the<br />

flowers have likely been exposed to improper temperatures during transportation<br />

and/or storage. Once unpacked, stems should be rehydrated and placed<br />

immediately in coolers at 33–35F (1–2C). Retailers must insist on proper cooling<br />

from suppliers and then consistently maintain proper temperatures at the retail<br />

outlet.<br />

Water temperature: Although water uptake is more rapid at warm temperatures<br />

than at cool, flower stems should not be placed in warm water unless<br />

needed. Some growers actually immerse stems up to the flowers in a deep bucket<br />

of cold water, creating a mini hydro-cooling system. Warm water is useful if<br />

flowers are particularly dehydrated coming out of the field or for bud opening.<br />

In such cases, water heated to 100–110F (38–43C) is most effective for rehydration.<br />

Using warm water seldom causes problems, but it is not particularly beneficial<br />

on a routine basis. Water at room temperature is fine for mixing floral<br />

preservatives unless otherwise noted by the manufacturer.<br />

Water quality: The water used for holding cut flowers affects the quality of the<br />

flower. Tap water is most commonly used; depending on the source, it may be<br />

high in salinity, vary in pH, or be contaminated with microorganisms. Sensitivity<br />

to saline conditions varies with species, but measurements of salinity must be<br />

treated with caution. More important is the measurement of the buffering<br />

capacity of the water, or its alkalinity. A salinity reading of 190 ppm appears

24 POSTHARVEST CARE<br />

dangerously high at first glance; however, the reading may consist of 40 ppm<br />

alkalinity and 150 ppm saline components. Such water is fine. The higher the<br />

alkalinity, the more difficult it is to adjust the pH of the water. This can be<br />

important when using preservatives. Most preservatives are effective at low pH<br />

(3.0–5.5), and if the pH cannot be adjusted, the preservative may be useless. Some<br />

preservative solutions work well in high alkaline waters, others do not. Knowing<br />

the alkalinity of the water used to treat cut flowers allows one to choose the most<br />

efficient preservative. Water may be tested through state universities or private<br />

laboratories for a reasonable price. It is money well spent.<br />

Flowers persist in acidic water longer than in basic pH water. Water that is<br />

acidic (pH 3.0–5.5) is taken up more rapidly and deters the growth of numerous<br />

microorganisms. The pH of the solution also affects the efficacy of the germicide<br />

in the preservative. Matching the proper preservative with the available water<br />

should result in good water quality and enhanced postharvest life of the flowers.<br />

Tap water often contains fluoride, which can be injurious to some cut flowers.<br />

The presence of as little as 1 ppm may injure gerberas, freesias, and other flowers.<br />

Snapdragons and other crops are less sensitive; daffodils, lilacs, and some<br />

orchids are insensitive.<br />

Depth of water: Relatively little water is absorbed through the walls of the stem<br />

(the majority is absorbed through the base), therefore the water or solution in<br />

which stems are held need not be deep, if stems are turgid or nearly so. The only<br />

advantage of plunging stems into 6" (15 cm) of water rather than 1" (2.5 cm) is<br />

that the water flows 6" (15 cm) up the water-conducting tissues of the stem,<br />

reducing the height the water must be moved by capillary action. Plunging stems<br />

in water more than 6" (15 cm) deep reduces air circulation around the leaves and<br />

crowds the stems and flowers together. If stems are severely wilted (often due to<br />

blockage by air bubbles), plunge them in water to a depth of at least 8" (20 cm);<br />

they will be more likely to revive than if put in shallow water (Nell and Reid 2000).<br />

Shipping wet or dry: Historically, shipping flowers in water was possible only for<br />

short distances; dry shipping (i.e., in boxes) is the norm when shipping by air or<br />

by truck, or when large volumes of flowers are involved. Some firms ship more<br />

fragile flowers across the country in innovative wet pack systems such as Procona<br />

and Freshpack. Brian Myrland of Floral Program Management points<br />

out a few of the many advantages to setting up a program based on this fastdeveloping<br />

technique: “Cutting stages [can] be tighter, more product [can] be<br />

packed in the wet pack, and less damage to open flowers [results].” Most wet<br />

packing is done by truck; however, transportation costs for air shipments are<br />

not as affected as one might anticipate, as air bills are often based on volume<br />

rather than weight. Retailers can use the containers as ready-to-sell, and shippers<br />

find that the expense continues to decline (Anon. 2000). Wet shipping methods<br />

will become far more popular as techniques improve and costs decline.<br />

Ethylene: Ethylene is released by all flowers, although ripening fruit and damaged<br />

flowers result in a significant increase in concentrations of the gas. It is also<br />

produced during the combustion of gasoline or propane and during welding.<br />

Low levels (

ylene, hold flowers in a cool, well-ventilated area, away from aging flowers or<br />

ripening fruit. The metal silver, which reduces the effects of ethylene, has historically<br />

been provided by silver thiosulfate (STS). This product, however, is not<br />

available in many states (see next section, on STS).<br />

The following genera are listed by Floralife, Inc., or Pokon & Chrysal as sensitive<br />

to ethylene. Not all are equally responsive to ethylene; for example, Rudbeckia<br />

is very much less sensitive and therefore less responsive to ethylene<br />

inhibitors than Delphinium.<br />

<strong>Achillea</strong><br />

Aconitum<br />

Agapanthus<br />

Alchemilla<br />

Allium<br />

Alstroemeria<br />

Anemone<br />

Anethum<br />

Antirrhinum<br />

Aquilegia<br />

Asclepias<br />

Astilbe<br />

Astrantia<br />

Bouvardia<br />

Callicarpa<br />

Campanula<br />

Celosia<br />

Centaurea<br />

Chamaelaucium<br />

Chelone<br />

[Clarkia]<br />

Consolida<br />

Crocosmia<br />

Curcuma<br />

Cymbidium<br />

Daucus<br />

Delphinium<br />

Dendrobium<br />

Dianthus<br />

Dicentra<br />

Digitalis<br />

Doronicum<br />

Echium<br />

Eremurus<br />

Eustoma<br />

Francoa<br />

Freesia<br />

Gladiolus<br />

Gypsophila<br />

Helianthus<br />

Ilex<br />

Ixia<br />

Juniperus<br />

Kniphofia<br />

Lathyrus<br />

Lavatera<br />

POSTHARVEST CARE 25<br />

Lilium<br />

Lysimachia<br />

Matthiola<br />

Narcissus<br />

Ornithogalum<br />

Paeonia<br />

Penstemon<br />

Phlox<br />

Physostegia<br />

Ranunculus<br />

Rosa<br />

Rudbeckia<br />

Saponaria<br />

Scabiosa<br />

Silene<br />

Solidago<br />

Trachelium<br />

Triteleia<br />

Trollius<br />

Tulipa<br />

Veronica<br />

Veronicastrum<br />

STS: In the late 1990s, silver thiosulfate (STS) was banned in the United<br />

States. In this country and abroad, the status of STS remains in a state of flux,<br />

and we asked postharvest expert Gay Smith of Pokon & Chrysal to clarify the situation.<br />

Her summary: Floralife essentially abandoned STS and threw their<br />

efforts into research and distribution of EthylBloc. Pokon & Chrysal started<br />

the registration process to get their STS solution, called AVB, approved by the<br />

EPA at federal and state levels; AVB received federal registration in September<br />

2001, then state-by-state registration began. Florida registration was approved<br />

in January 2002; approval in California and other states is expected in the near<br />

future. But STS was never banned in South or Central America, and flowers can<br />

still be treated at the grower level in South and Central American countries. In<br />

fact, some California growers moved production of ethylene-sensitive crops (e.g.,<br />

delphinium, satin flower) to Mexico so they could continue to treat them.

26 POSTHARVEST CARE<br />

Aquilegia hybrid<br />

Pulsing: Placing freshly harvested flowers for a short time (a few seconds to<br />

several hours) in a solution to extend vase life is referred to as pulsing. Hydration<br />

solutions, sugar, and STS are common pulsing ingredients; short pulses (10 seconds)<br />

of silver nitrate (100–200 ppm) have also been successful with a few species.<br />

Silver nitrate, however, is seldom used commercially.<br />

Removal of leaves: As a rule, ⅓ of the leaves are removed from the base of the<br />

stem, and in some cases all leaves are removed, especially if flowers will be dried.<br />

Foliage immersed in water leads to bacterial growth and toxin buildup, reducing<br />

the postharvest life of the flower.<br />

Clean buckets: At every conference, at every meeting, and at every farm, the<br />

importance of clean buckets is discussed. This is not arguable—it is as basic as a<br />

surgeon scrubbing up before an operation. Buckets must be cleaned with soap,<br />

and a protocol to wash them must be established. Why go to all the trouble and<br />

expense of growing a crop only to lose it in the bucket?

Dicentra spectabilis<br />

POSTHARVEST CARE 27<br />

Availability of food: Since few or no leaves are cut along with flowers, little food<br />

is available to the stem and flower. The quality and longevity of cut flowers are<br />

improved when stems are pulsed in a solution containing sucrose or table sugar.<br />

In general, concentrations of 1.5–2% sugar are used, although higher concentrations<br />

are effective for certain species. Most commercial preservatives contain<br />

approximately 1% sugar, which is sufficient for most flowers. Sugar solutions<br />

can be made up, if necessary, by the grower. Add 13 oz of sucrose to 10 gallons of<br />

water per percentage required. That is, for a 1% solution, dissolve 13 oz (370 g)<br />

of sucrose in 10 gallons (38 l) of water; for a 4% solution, add 52 oz (1482 g) to 10<br />

gallons (38 l) of water.<br />

Air bubbles: Air bubbles, which restrict the upward flow of water, occur after<br />

harvesting with many types of flower stems. Recutting stems (approximately 1",<br />

2.5 cm) under water reduces the blockages. Nell and Reid (2000) suggest a creative<br />

home remedy for rehydration. Fill a soft plastic container, like a 1 gallon<br />

(4 l) milk jug, to the top with hot water (150–160F, 65–71C). Cap it and place it<br />

in the refrigerator or cooler. As the water cools, the container shrinks, air is<br />

excluded, and the remaining water is air-free. When stems with trapped air in<br />

their stems are placed in this water, the water acts as a scavenger for the trapped<br />

air and removes it from the stems. Flowers placed into degassed water will<br />

hydrate quickly. Placing stems in citric acid (pH 3.5) also reduces air emboli.<br />

Cutting stems under water: Staby (2000) reinvestigated the benefit of cutting<br />

stems under water. After all, it is an inconvenient practice, and if there really is no<br />

difference between cutting in air or under water, then it need not be done. He<br />

found that if plants rehydrate properly when put in water, it does not matter<br />

how they are recut, but that most do rehydrate faster when recut under water.<br />

His most important finding was that if the water under which the stems are cut<br />

is contaminated (excessive levels of microorganisms, dirt, debris, sap from stems<br />

being cut), it is better to cut the stems in air. Of course, cutting under clean water

28 POSTHARVEST CARE<br />

extends vase life anyway, so keep the water fresh. Add household bleach to the<br />

water, and rinse the bottom half of the flower stems before cutting under water.<br />

Bacteria can also block the ends of stems. Clean containers and acidified<br />

water greatly reduce this problem, as do commercial floral preservatives, which<br />

contain antibacterial and antifungal agents, such as 8-hydroxyquinoline citrate<br />

or sulfate (8-HQC, 8-HQS). Additional agents should not be necessary.<br />

Conditioning: Conditioning or hardening of cut stems restores the turgor of<br />

wilted flowers. In general, demineralized water should be used when conditioning<br />

solutions are prepared. When stems are placed in solutions, they should be<br />

held at room temperature initially (a few hours to overnight) then placed in cold<br />

storage for several hours. Warm water (110F, 43C) is highly recommended for<br />

restoring turgor only in badly wilted stems. Badly wilted stems, especially those<br />

with woody stems, may benefit from being placed in hot water (180–200F, 82–<br />

93C) prior to being placed in room temperature solutions.<br />

Postharvest Solutions<br />

Rehydration solutions: This is an essential step after harvest. Freshly harvested<br />

flower stems are placed in water to restore turgidity, a process called rehydration.<br />

Rehydration solutions contain no sugar and are essentially used to jumpstart<br />

the flow of water through the plant’s plumbing system. They include a germicide<br />

and wetting agent and have a pH around 3.5. If possible, rehydration<br />

should take place immediately after cutting.<br />

Pulsing solutions: Generally, pulsing solutions are used to provide sugars<br />

(sucrose or glucose, 2–20% added to flower food) and silver compounds (STS),<br />

and occasionally to reduce leaf yellowing (cytokinins) and as a germicide (5- to<br />

10-second silver nitrate dip on specific crops). The uptake of all solutions is<br />

affected by both the temperature of the solution and the temperature of the air.<br />

Colder temperatures require a longer pulsing period than warmer temperatures.<br />

Bud-opening solutions: Flowers that are cut bud-tight respond to bud-opening<br />

solutions prior to sale to the final consumer. These consist mainly of a fresh<br />

flower food and additional sugar. Nell and Reid (2000) suggest that bud-opening<br />

solutions be used at 70–75F (21–24C), 60–80% relative humidity, and relatively<br />

high light.<br />

Fresh flower food: These solutions are known and sold as flower preservatives,<br />

but the term “fresh flower food” is kinder and gentler, and that is a good thing.<br />

Most consist of sugar (the food), a biocide to reduce bacterial growth, and an<br />

acid to reduce the pH; sometimes they contain a growth regulator to reduce leaf<br />

yellowing or an anti-ethylene substance. Fresh flower food can increase vase life<br />

up to 75% (Nell and Reid 2000), and while not all flowers will respond dramatically,<br />

few will be harmed by the products.<br />

In-house mixing: Flower preservatives, silver solutions, bactericides, bud openers,<br />

conditioners, and sugar solutions are all part of the postharvest jargon.<br />

While these various components can be mixed in the back room, what is the<br />

point? It is doubtful that homemade solutions will significantly differ from commercial<br />

mixes, and often mistakes are made in the process, resulting in solu-

POSTHARVEST CARE 29<br />

tions that are either ineffective or phytotoxic. A grower is a busy enough, already<br />

functioning as farmer, market analyst, and information gatherer combined.<br />

Why add chemist, waste disposal technician, and preservative manufacturer to<br />

the list? Preservative companies provide information, effective chemicals, and<br />

good service. Growers don’t manufacture insecticides, why should they concoct<br />

preservatives? Last but not least, it is illegal to manufacture preservatives “inhouse”<br />

without necessary Materials Safety Data Sheets.<br />

Some mixing is always necessary. That is why we learn to read, so routine<br />

flower preservatives can be mixed properly. Almost always, when flower foods are<br />

mixed improperly, they are used at weaker-than-recommended levels (Staby<br />

2000). When insufficient amounts of floral food are used, the sugar in the food<br />

actually promotes the growth of microorganisms because there is insufficient<br />

biocide to control them. Better to use no flower food at all than one that is mixed<br />

improperly. Do some simple tests on your own to determine which flower food<br />

or other chemical is best for your flowers.<br />

Reading<br />

Anon. 2000. Fill ’em up, ship ’em out. Florists’ Review (Nov.):88–90.<br />

Holstead-Klink, C. 1992. Postharvest handling of fresh flowers. In Proc. 4th Natl.<br />

Conf. on Specialty Cut Flowers. Cleveland, Ohio.<br />

Nell, T. A., and M. S. Reid. 2000. Flower and Plant Care. Society of American Florists,<br />

Alexandria, Va.<br />

Reid, M. S. 2000. Some like it cold. Florists’ Review (Nov.):82–84.<br />

Rij, R. E., J. F. Thompson, and D. Farnham. 1979. Handling, precooling, and<br />

temperature management of cut flowers for truck transportation. In Advances<br />

in Agricultural Technology AAT-W-5 (June). USDA, Sci. and Edu. Admin.<br />

Staby, G. 2000. The latest on cut flower processing. Florists’ Review (Nov.):86.<br />

Many thanks to George Staby, Christy Holstead-Klink, Gay Smith, and Brian<br />

Myrland for reviewing this section.

DRYING AND PRESERVING<br />

Dried flowers are an important segment of the specialty market. Growers of<br />

dried flowers must be efficient because their products may be shipped from anywhere<br />

at any time. Quality, however, is still a significant marketing advantage.<br />

Producers who provide dried material should do so as a primary focus, not as<br />

means of using up unsold fresh production. Cultural methods, harvest stage,<br />

and postharvest techniques differ for dried production. Two ways to go out of<br />

business: thinking that “material that could not be sold fresh can always be<br />

dried” and that “material of inferior quality for fresh can always be dried.” Garbage<br />

in equals garbage out. “Fresh” dried material—harvested at the optimum<br />

stage, treated correctly, and smartly displayed—can compete with flowers anywhere<br />

and is far more appealing than leftovers dried as an afterthought.<br />

Dried materials are not “dead sticks and twigs,” but include colorful flowers,<br />

preserved fruits, and soft, supple stems whose postharvest life is far superior to<br />

that of fresh material. Significant gains in methods for rapid drying have been<br />

made in recent years, methods that maintain the color, shape, and size of the<br />

plant material. But methods are often poorly excecuted, and materials useful<br />

for drying misunderstood. It is wrong to believe that dried flowers are easier to<br />

produce than fresh; in fact, dried flower producers must produce a high-quality<br />

fresh product before the process of drying even begins. The highest-quality<br />

dried material begins with the highest-quality fresh material, and the trend in<br />

the marketplace is to grow for the fresh market or the dried market, but not<br />

both.<br />

Dried flower producers face a great deal of competition from plastics, silks,<br />

and other faux products. According to Shelley McGeathy of Hemlock, Mich.,<br />

who has been producing dried material for many years, “It is more important<br />

than ever to produce top-quality, incredibly colored dried materials. Only outstanding<br />

preserved products will keep the market strong for dried materials.” So<br />

the questions beg to be asked. What should one expect from dried materials?<br />

And how is that elusive excellent quality attained?<br />

In answer to the first question, Mark Koch of Robert Koch Industries suggests<br />

that dried floral products should have a minimum useful life of one year.<br />

As to the second, he has produced an excellent series of technical bulletins on the<br />

many aspects of drying floral product; the information contained therein is easy<br />

30

DRYING AND PRESERVING 31<br />

to comprehend, and they should be read by anyone involved in the cut flower<br />

business. They are available through Robert Koch Industries, Bennett, Colo.<br />

Much of the information in this section is based on Mark’s work.<br />

Drying<br />

Air drying: Air drying is the most widely used method for preserving material:<br />

it’s simple, it allows a large volume of material to be processed, and it requires<br />

low capital investment. In passive air drying, the most common process, plant<br />

materials are dried in an uncontrolled environment, like a barn or converted<br />

shed. Active air drying is a controlled process that directs heated air across the<br />

plant surfaces; it requires a furnace or other heat source and fans and blowers to<br />

direct the heat. The advantages of active air drying are more rapid drying and the<br />

ability to control humidity and eradicate insects.<br />

Plants for drying: In general, plant material with a high water content (e.g.,<br />

peonies) do not dry as well as those with a moderate or low moisture volume.<br />

Delicate flowers (iris, carnations) are more difficult to air dry than tougher flowers<br />

(sinuata statice). Tropical flowers do not air dry well. Essentially, materials<br />

with a higher lignin content tend to be easier to dry than those with a high water<br />

content. Unfortunately, flowers that do not dry well are equally difficult to preserve<br />

with glycerine treatments. Some flowers with high water content are more<br />

easily dried using freeze-dry techniques. Roses, calla lilies, and peonies can all be<br />

freeze-dried and preserved for many years.<br />

Facilities for air drying: Drying sheds range from basements to elaborate greenhouses<br />

or storage areas with sophisticated equipment. Whether flowers are dried<br />

in the attic or in converted warehouse space, all sheds must have a few characteristics<br />

in common. Protection from excessive sunlight, wind, water, and dust<br />

is important. Concrete floors are expensive but highly recommended. Not only<br />

do they act as excellent heat sinks, warming up during the day and slowly releasing<br />

heat at night, they also reduce dust. Dust particles become permanently<br />

attached to stems that have been treated with sealers or flame retardants. Dirt<br />

floors are never recommended; however, gravel floors have been used successfully.<br />

Lining floors with straw or wood shavings is done, but these materials can<br />

be a haven for insects. Protection from insects and rodents can be accomplished<br />

through screens.<br />

Ventilation is another important consideration. During the drying process,<br />

materials release moisture to the air. Without adequate air movement, drying<br />

rates are considerably prolonged. Sheds should be constructed to take advantage<br />

of natural ventilation (e.g., prevailing winds), but fans are often incorporated to<br />

aid air circulation. Poor air movement also encourages the buildup of molds<br />

and disease organisms. If fumigation is necessary to kill insects, the shed must<br />

be airtight. Some drying sheds are constructed so that all or a portion of space<br />

may be sealed for fumigant application and then properly vented in keeping<br />

with regulatory statutes.<br />

The rate of drying increases with increasing temperature and decreasing<br />

humidity. Plant materials with waxy cuticles and large stem diameters take

32 DRYING AND PRESERVING<br />

longer to dry; so do those with high moisture content. Temperatures in the drying<br />

shed vary widely, averaging 70–120F (21–49C). Humidity levels are seldom<br />

controlled by smaller producers and generally reflect the outside humidity. Airdrying<br />

equipment with humidity and temperature control is popular with larger<br />

processors and those whose natural environment is humid. Optimum humidity<br />

levels of 20–60% should be monitored by all processors.<br />

Some materials are best dried in darkness, others in sunlight. Drying sheds<br />

with the ability to adjust the amount of light will allow the grower to dry a range<br />

of materials. Most plant materials, when exposed to sunlight, fade to pale yellow,<br />

which is advantageous when material is to be dyed—a pastel shade is easier to<br />

color than green. This sun bleaching is used by many processors in preparation<br />

for drying; grasses, for example, must be bleached if light color shades are to be<br />

produced. Sun bleaching also provides an autumnal look for grasses, grains,<br />

and thin-stemmed flowers. If the natural plant color is to be retained, drying in<br />

the absence of light is recommended.<br />

Required drying times: Drying times vary considerably, depending on species,<br />

location, drying shed design, and season. Drying times also depend on the<br />

amount of water in the fresh material and the desired water content of the dried<br />

product. This is known as the dry fraction. Dry fractions for all crops are best<br />

obtained by doing simple weighing experiments at the beginning and end of the<br />

drying cycle. This can be done by occasionally weighing individual bunches; to<br />

obtain the dry fraction, divide the dry weight of the plant by the fresh weight. For<br />

example, sinuata statice is approximately 70% water, therefore the dry fraction is<br />

30% (or 0.3). If 100 pounds (46 kg) of fresh sinuata statice is to be dried, drying<br />

is complete when the weight is 30 pounds (13.6 kg). In general, drying times<br />

range from 3 days to 2 weeks in a passive system. In an active system, plant materials<br />

typically dry in 24 hours or less. Failure to adequately dry a plant can lead<br />

to serious mold problems if material is sleeved and boxed too early.<br />

Bunch size and handling: Stems are generally grouped in bunches for resale.<br />

Bunch size is determined by the desired weight of the dried product and the dry<br />

weight fraction of that product. If the final weight of a dried bunch of sinuata<br />

statice (dry weight fraction = 0.3) is to be 4 ounces (114 g), then the initial fresh<br />

bunch weight should be 4/0.3 or 13.3 ounces (379 g). Bunches with too many<br />

stems may reduce air circulation within the bunch, and bunches should not be<br />

placed so close together as to reduce air movement between them. They are normally<br />

hung on strings or wires from the roof, and it is common to date each line<br />

as stems are hung, to ensure proper drying times. In active systems, plants are<br />

often placed on drying racks that can be rolled into the drying chamber.<br />

Mold and insect problems: Poor air circulation, prolonged periods of high<br />

humidity, excessively large bunch size, and overcrowding in the drying facility<br />

are common causes of mold formation. Low humidity and adequate air flow<br />

greatly reduce mold problems. Insects can be treated with chemicals, but these<br />

are highly restricted and require licensing. Heat is an effective way to reduce<br />

insect problems but is usually only possible in active systems or in passive systems<br />

where a heat source is available. Mark Koch (1996a) suggests the following<br />

exposures to control insects:

Drying temperature Exposure time<br />

110F (43C) 24 hours<br />

120F (49C) 3 hours<br />

150F (66C) 20 minutes<br />

DRYING AND PRESERVING 33<br />

Storage after drying: Material is usually boxed and stored after drying. Boxes<br />

should be stored in a pest-free area with low humidity. Air temperatures should<br />

be low but are not as important as low humidity.<br />

Glycerine<br />

The replacement of water with glycerine results in soft, pliable plants that behave<br />

as if they have been preserved. Material to be preserved should be treated as soon<br />

after harvest as possible. For most plants, incorporation of glycerine is accomplished<br />

through systemic uptake through the base of the stem. In general, 1 part<br />

of glycerine, mixed with 3 parts hot water (by volume), and a surfactant, to<br />

reduce the surface tension of water, is recommended. Avoid using tall buckets,<br />

which reduce air circulation around the leaves; place stems in approximately 3"<br />

(8 cm) of solution in a well-ventilated area indoors at 70–85F (21–29C). After<br />

treatment, the portion of the stems immersed in glycerine/dye should be<br />

removed; the solution bleeds from the treated area otherwise. In general, the<br />

smaller the diameter of the stem, the less glycerine is used. Normal preserving<br />

time is 3–7 days. Water-soluble dyes may be added at the same time.<br />

If stems are allowed to remain in glycerine too long, the glycerine will move<br />

through the plants and be pumped out through the flowers and foliage, resulting<br />

in stems that may be wet, oily, and essentially unusable. After treating, the<br />

stems should be rinsed with clear water and hung to dry. If stems are still not sufficiently<br />

soft 4–5 days after removal from the glycerine, a misting of the glycerine<br />

solution over the foliage helps to make them more supple. A drying time of<br />

about 1–2 weeks is necessary. Most plants are preserved in the dark; however,<br />

eucalyptus is light-treated, and baby’s breath is preserved in the light to give an<br />

amber glow to the stems and flowers. The glycerine solution may be reused up to<br />

3 times; simply pour through a fine screen to remove leaves and other debris. If<br />

the solution is to be stored for more than a week or used over a long period of<br />

time, antimicrobial agents, such as potassium sorbate and citric acid, should be<br />

added (Koch 1996b).<br />

Some plants do not absorb glycerine well and must be immersed in the glycerine<br />

solution, for 1–2 days if the solution is unheated, for 6–12 hours if heated<br />

to 180F (82C). As with the absorption method, material is removed, rinsed, and<br />

hung to dry for 1–2 weeks.<br />

Freeze-drying<br />

Freeze-drying allows the water in plants to pass from the solid state (frozen) to<br />

the vapor state (steam) without passing through the liquid phase. Advances in

34 DRYING AND PRESERVING<br />

freeze-drying equipment and polymer chemistry have resulted in more and more<br />

flowers being freeze-dried, particularly stems and flowers with high water content.<br />

Small equipment designed for the florist industry is available, as well as<br />

high-volume dryers for wholesalers and wholesale growers. Freeze-drying provides<br />

flowers with a natural shape and color and extended longevity. Freezedrying<br />

is highly technical and requires a significant capital investment; however,<br />

it creates a marvelous product and is a viable method for delicate flowers.<br />

Silica Gel<br />

For many dried products, the water in the plant is transferred to a desiccant,<br />

such as silica gel. Plants are completely embedded in the gel and remain there<br />

until all the water has been removed. The main benefits of silica gel are excellent<br />

retention of color and shape. Useful flowers to treat with gel are those with<br />

high moisture content and little fiber, such as zinnias and sunflowers. Stems<br />

seldom dry well with silica gel, and flowers dried by this method are cut with<br />

very little stem remaining. Silica gel can be reactivated after use by heating in an<br />