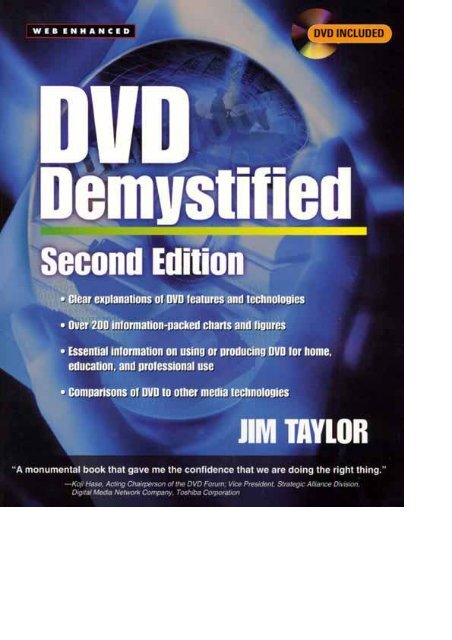

DVD Demystified

DVD Demystified

DVD Demystified

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TEAMFLY

<strong>DVD</strong> DEMYSTIFIED

This page intentionally left blank.

<strong>DVD</strong><br />

<strong>Demystified</strong><br />

Jim Taylor<br />

Second Edition<br />

McGraw-Hill<br />

New York San Francisco Washington, D.C.<br />

Auckland Bogotá Caracas Lisbon London<br />

Madrid Mexico City Milan Montreal New Delhi<br />

San Juan Singapore Sydney Tokyo Toronto

McGraw-Hill<br />

abc<br />

Copyright © 2001 by The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted<br />

under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by<br />

any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.<br />

0-07-138944-X<br />

The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-135026-8.<br />

All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked<br />

name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement<br />

of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps.<br />

McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate<br />

training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at george_hoare@mcgraw-hill.com or (212)<br />

904-4069.<br />

TERMS OF USE<br />

This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the<br />

work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and<br />

retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works<br />

based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent.<br />

You may use the work for your own noncommercial and personal use; any other use of the work is strictly prohibited. Your right<br />

to use the work may be terminated if you fail to comply with these terms.<br />

THE WORK IS PROVIDED “AS IS”. McGRAW-HILL AND ITS LICENSORS MAKE NO GUARANTEES OR WARRANTIES<br />

AS TO THE ACCURACY, ADEQUACY OR COMPLETENESS OF OR RESULTS TO BE OBTAINED FROM USING THE<br />

WORK, INCLUDING ANY INFORMATION THAT CAN BE ACCESSED THROUGH THE WORK VIA HYPERLINK OR<br />

OTHERWISE, AND EXPRESSLY DISCLAIM ANY WARRANTY, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED<br />

TO IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. McGraw-Hill and its<br />

licensors do not warrant or guarantee that the functions contained in the work will meet your requirements or that its operation will<br />

be uninterrupted or error free. Neither McGraw-Hill nor its licensors shall be liable to you or anyone else for any inaccuracy, error<br />

or omission, regardless of cause, in the work or for any damages resulting therefrom. McGraw-Hill has no responsibility for the content<br />

of any information accessed through the work. Under no circumstances shall McGraw-Hill and/or its licensors be liable for any<br />

indirect, incidental, special, punitive, consequential or similar damages that result from the use of or inability to use the work, even<br />

if any of them has been advised of the possibility of such damages. This limitation of liability shall apply to any claim or cause whatsoever<br />

whether such claim or cause arises in contract, tort or otherwise.<br />

DOI: 10.1036/007138944X

To my wife, Julia, who would have preferred more<br />

me and less book, but who was amazingly supportive<br />

through the entire long endeavor.

PRAISE FOR <strong>DVD</strong> DEMYSTIFIED<br />

It was on Aril 17, 1992, when four bottles of Napa red wine were emptied<br />

between Warran Lieberfarb (President, Warner Home Video) and myself,<br />

that the very first shape of the <strong>DVD</strong> concept was originated. I was very<br />

excited but nevertheless seriously anxious about whether this new technology<br />

would ever see the light of the multimedia age.<br />

Then, in early 1998, when I learned that <strong>DVD</strong> <strong>Demystified</strong> had been<br />

published, was the very first time I began to feel there was proof that <strong>DVD</strong><br />

was heading for success.<br />

I met with Jim in San Francisco later and got his book with his autograph.<br />

It sits nicely on my shelf as a monumental book that gave me the<br />

confidence that we are doing the right thing. His new edition, as a reference<br />

to executives and engineers, will surely add stability for the evergrowing<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> market.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> will continue to penetrate into every corner of our lives. It will be<br />

a pervasive technology for probably a couple of decades to come. I have<br />

the feeling that <strong>DVD</strong> <strong>Demystified</strong> will continue in several more editions<br />

over the years as a benchmark reference of this technology.<br />

Koji Hase<br />

Acting Chairperson of the <strong>DVD</strong> Forum<br />

Vice President, Strategic Alliance Division,<br />

Digital Media Network Company, Toshiba Corporation<br />

A clear and intelligent guide to <strong>DVD</strong>, and a valuable reference for anyone<br />

who wants to take full advantage of the technology.<br />

Kamer Davis, Senior Vice President,<br />

Ogilvy Public Relations Worldwide<br />

Required reading for both novices and professionals interested in the<br />

fundamentals of <strong>DVD</strong>, and required reading for all InterActual employees.<br />

Todd Collart, President & CEO,<br />

InterActual Technologies, Inc.<br />

Copyright 2001 The McGraw-Hill Companies. Click Here for Terms of Use.

CONTENTS<br />

Foreword xix<br />

Acknowledgments xxi<br />

Preface xxiii<br />

Chapter 1 What Is <strong>DVD</strong>? 1<br />

Introduction 2<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video versus <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM 4<br />

What Does <strong>DVD</strong> Portend? 5<br />

Who Needs to Know About <strong>DVD</strong>? 6<br />

Movies 6<br />

Music and Audio 7<br />

Music Performance Video 7<br />

Training and Productivity 8<br />

Education 8<br />

Computer Software 9<br />

Computer Multimedia 9<br />

Video Games 10<br />

Information Publishing 10<br />

Marketing and Communications 11<br />

And More ... 11<br />

About This Book 12<br />

Units and Notation 13<br />

Other Conventions 16<br />

Chapter 2 The World Before <strong>DVD</strong> 19<br />

A Brief History of Audio Technology 20<br />

A Brief History of Video Technology 24<br />

Captured Light 27<br />

Dancing Electrons 29<br />

Metal Tape and Plastic Discs 31<br />

The Digital Face-Lift 34<br />

A Brief History of Data Storage Technology 37<br />

Innovations of CD 39<br />

The Long Gestation of <strong>DVD</strong> 45<br />

Hollywood Weighs In 45<br />

Dissension in the Ranks 47<br />

Copyright 2001 The McGraw-Hill Companies. Click Here for Terms of Use.

viii<br />

Contents<br />

The Referee Shows Up 48<br />

Reconciliation 49<br />

Product Plans 52<br />

Turbulence 53<br />

Glib Promises 54<br />

Sliding Deadlines and Empty Announcements 55<br />

The Birth of <strong>DVD</strong> 58<br />

Disillusionment 60<br />

Divx: A Tale of Two <strong>DVD</strong>s 63<br />

Ups and Downs 67<br />

The Second Year 69<br />

The Second Wind 71<br />

The Year of <strong>DVD</strong> 74<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> Gets Connected 75<br />

Patents and Protections 76<br />

Blockbusters and Logjams 77<br />

Crackers 79<br />

The Medium of the New Millennium 80<br />

That’s No Moon, That’s a PlayStation! 82<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> Turns Four 86<br />

Chapter 3 <strong>DVD</strong> Technology Primer 87<br />

Introduction 88<br />

Gauges and Grids: Understanding Digital and Analog 88<br />

Birds Over the Phone: Understanding Video Compression 90<br />

Compressing Single Pictures 94<br />

Compressing Moving Pictures 95<br />

Birds Revisited: Understanding Audio Compression 102<br />

Perceptual Coding 103<br />

MPEG-1 Audio Coding 104<br />

MPEG-2 Audio Coding 105<br />

Dolby Digital Audio Coding 106<br />

DTS Audio Coding 107<br />

MLP Audio Encoding 108<br />

Effects of Audio Encoding 108<br />

A Few Timely Words about Jitter 109<br />

Pegs and Holes: Understanding Aspect Ratios 115<br />

How It Is Done with <strong>DVD</strong> 120<br />

Widescreen TVs 125

Contents ix<br />

Aspect Ratios Revisited 127<br />

Why 16:9? 129<br />

The Transfer Tango 132<br />

Summary 133<br />

The Pin-Striped TV: Interlaced versus Progressive Scanning 135<br />

Progressive <strong>DVD</strong> Players 138<br />

Chapter 4 <strong>DVD</strong> Overview 143<br />

Introduction 144<br />

The <strong>DVD</strong> Family 144<br />

The <strong>DVD</strong> Format Specification 146<br />

Compatibility 147<br />

Physical Compatibility 149<br />

File System Compatibility 152<br />

Application Compatibility 153<br />

Implementation Compatibility 153<br />

New Wine in Old Bottles: <strong>DVD</strong> on CD 154<br />

Compatibility Initiatives 155<br />

Bells and Whistles: <strong>DVD</strong>-Video and <strong>DVD</strong>-Audio Features 157<br />

Over 2 Hours of High-Quality Digital Video and Audio 158<br />

Widescreen Movies 159<br />

Multiple Surround Audio Tracks 159<br />

Karaoke 160<br />

Subtitles 160<br />

Different Camera Angles 161<br />

Multistory Seamless Branching 161<br />

Parental Lock 162<br />

Menus 162<br />

Interactivity 163<br />

On-Screen Lyrics and Slideshows 163<br />

Customization 164<br />

Instant Access 164<br />

Special Effects Playback 164<br />

Access Restrictions 164<br />

Durability 165<br />

Programmability 165<br />

Availability of Features 165<br />

Beyond <strong>DVD</strong>-Video and <strong>DVD</strong>-Audio Features 166

x<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> Myths 166<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Is Revolutionary” 166<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Will Fail” 167<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Is a Worldwide Standard” 168<br />

Myth: “Region Codes Do Not Apply to Computers” 168<br />

Myth: “A <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM Drive Makes Any PC a Movie Player” 168<br />

Myth: “Competing <strong>DVD</strong>-Video Formats are Available” 169<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Players Can Play CDs” 169<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Is Better Because It Is Digital” 170<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Video Is Poor Because It Is Compressed” 170<br />

Myth: “Compression Does Not Work for Animation” 172<br />

Myth: “Discs Are Too Fragile to Be Rented” 172<br />

Myth: “Dolby Digital Means 5.1 Channels” 173<br />

Myth: “The Audio Level from <strong>DVD</strong> Players Is Too Low”<br />

Myth: “Downmixed Audio Is No Good because<br />

174<br />

the LFE Channel Is Omitted”<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Lets You Watch Movies as They<br />

174<br />

Were Meant to Be Seen” 174<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Crops Widescreen Movies” 175<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Will Replace Your VCR” 175<br />

Myth: “People Will Not Collect <strong>DVD</strong>s Like They Do CDs” 175<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Holds 4.7 to 18 Gigabytes” 176<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong> Holds 133 Minutes of Video” 176<br />

Myth: “<strong>DVD</strong>-Video Runs at 4.692 Mbps”<br />

Myth: “Some Units Cannot Play Dual-Layer or<br />

177<br />

Double-Sided Discs” 178<br />

Bits and Bytes and Bears 179<br />

Pits and Marks and Error Correction 179<br />

Layers 181<br />

Variations and Capacities of <strong>DVD</strong> 183<br />

Hybrids 185<br />

Regional Management 187<br />

Content Protection 190<br />

Licensing 204<br />

Packaging 208<br />

TEAMFLY<br />

Contents<br />

Chapter 5 Disc and Data Details 211<br />

Introduction 212<br />

Physical Composition 212<br />

Substrates and Layers 212

Contents xi<br />

Mastering and Stamping 215<br />

Bonding 218<br />

Burst Cutting Area 219<br />

Optical Pickups 220<br />

Media Storage and Longevity 221<br />

Writable <strong>DVD</strong> 223<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-R 224<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-RW 227<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-RAM 228<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>+RW 232<br />

Phase-Change Recording 233<br />

Real-Time Recording Mode 233<br />

Summary of Writable <strong>DVD</strong> 234<br />

Data Format 237<br />

Sector Makeup and Error Correction 237<br />

Data Flow and Buffering 241<br />

Disc Organization 242<br />

File Format 243<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-ROM Premastering 246<br />

Improvement over CD 246<br />

Chapter 6 Application Details: <strong>DVD</strong>-Video and <strong>DVD</strong>-Audio 249<br />

Introduction 250<br />

Data Flow and Buffering 250<br />

File Format 254<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video 255<br />

Navigation and Presentation Overview 257<br />

Physical Data Structure 260<br />

Domains and Spaces 267<br />

Presentation Data Structure 268<br />

Navigation Data 269<br />

Summary of Data Structures 279<br />

Menus 282<br />

Buttons 284<br />

Stills 285<br />

User Operations 286<br />

Video 286<br />

Audio 299<br />

Subpictures 309

xii<br />

Contents<br />

Closed Captions 311<br />

Camera Angles 311<br />

Parental Management 313<br />

Seamless Playback 314<br />

Text 315<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Audio 320<br />

Data Structures 321<br />

Navigation 324<br />

Bonus Tracks 324<br />

Audio Formats 324<br />

High-Frequency Audio Concerns 326<br />

Downmixing 328<br />

Stills and Slideshows 328<br />

Text 328<br />

Super Audio CD (SACD) 329<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> Recording 330<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-VR 331<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-AR 332<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-SR 332<br />

Chapter 7 What’s Wrong with <strong>DVD</strong> 335<br />

Introduction 336<br />

Regional Management 336<br />

Copy Protection 337<br />

Hollywood Baggage on Computers 339<br />

NTSC versus PAL 339<br />

Tardy <strong>DVD</strong>-Audio 340<br />

Incompatible Recordable Formats 341<br />

Late-Blooming Video Recording 341<br />

Playback Incompatibilities 342<br />

Synchronization Problems 343<br />

Feeble Support of Parental Choice Features 343<br />

Not Better Enough 344<br />

No Reverse Gear 345<br />

Only Two Aspect Ratios 345<br />

Deficient Pan and Scan 346<br />

Inefficient Multitrack Audio 346<br />

Inadequate Interactivity 347<br />

Limited Graphics 348

Contents xiii<br />

Small Discs 348<br />

False Alarms 349<br />

No Bar-Code Standard 349<br />

No External Control Standard 349<br />

Poor Computer Compatibility 350<br />

No Web<strong>DVD</strong> Standard 350<br />

Escalated Obsolescence 351<br />

Summary 351<br />

Chapter 8 <strong>DVD</strong> Comparison 353<br />

Introduction 354<br />

Laserdisc and CD-Video (CDV) 354<br />

Advantages of <strong>DVD</strong>-Video over Laserdisc 355<br />

Advantages of Laserdisc over <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 360<br />

Compatibility of Laserdisc and <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 361<br />

Videotape 361<br />

Advantages of <strong>DVD</strong>-Video over Videotape 362<br />

Advantages of Videotape over <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 364<br />

Compatibility of VHS and <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 365<br />

Digital Videotape (DV, Digital8, and D-VHS) 366<br />

Advantages of <strong>DVD</strong>-Video over DV 368<br />

Advantages of DV over <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 370<br />

Compatibility of DV and <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 371<br />

Audio CD 371<br />

Advantages of <strong>DVD</strong> over Audio CD 371<br />

Advantages of Audio CD over <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 374<br />

Compatibility of Audio CD and <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 374<br />

CD-ROM 374<br />

Advantages of <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM over CD-ROM 375<br />

Advantages of CD-ROM over <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM 377<br />

Compatibility of CD-ROM and <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM 378<br />

Video CD and CD-i 378<br />

Advantages and Disadvantages of CD-i 380<br />

Advantages of <strong>DVD</strong>-Video over Video CD 381<br />

Advantages of Video CD over <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 382<br />

Compatibility of CD-i and <strong>DVD</strong> 383<br />

Compatibility of Video CD and <strong>DVD</strong> 383<br />

Super Video CD 383<br />

Advantages of <strong>DVD</strong>-Video over SVCD 384

xiv<br />

Contents<br />

Advantages of SVCD over <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 385<br />

Compatibility of SVCD and <strong>DVD</strong> 385<br />

Other CD Formats 385<br />

Compatibility of CD-R and <strong>DVD</strong> 386<br />

Compatibility of CD-RW and <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM 386<br />

Compatibility of Photo CD and <strong>DVD</strong> 386<br />

Compatibility of Enhanced CD (CD Extra) and <strong>DVD</strong> 387<br />

Compatibility of CDG and <strong>DVD</strong> 387<br />

MovieCD 387<br />

MiniDisc (MD) and DCC 388<br />

Advantages of <strong>DVD</strong>-Video over MiniDisc 388<br />

Advantages of MiniDisc over <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 390<br />

Compatibility of MiniDisc and <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 390<br />

Digital Audiotape (DAT) 390<br />

Advantages of <strong>DVD</strong> over DAT 391<br />

Advantages of DAT over <strong>DVD</strong> 392<br />

Compatibility of DAT and <strong>DVD</strong> 392<br />

Magneto-Optical (MO) Drives 392<br />

Advantages of <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM over MO 393<br />

Advantages of MO over <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM 394<br />

Compatibility of MO and <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM 394<br />

Other Removable Data Storage 394<br />

Chapter 9 <strong>DVD</strong> at Home 395<br />

Introduction 396<br />

Choosing a <strong>DVD</strong> Player 396<br />

How to Hook Up a <strong>DVD</strong> Player 398<br />

Signal Spaghetti 398<br />

Connector Soup 400<br />

Audio Hookup 403<br />

A Bit About Bass 408<br />

Video Hookup 409<br />

Digital Hookup 411<br />

How to Get the Best Picture and Sound 412<br />

Viewing Distance 413<br />

THX Certification 414<br />

Software Certification 414<br />

Hardware Certification 416<br />

Understanding Your <strong>DVD</strong> Player 416

Contents xv<br />

Remote Control and Navigation 417<br />

Player Setup 417<br />

Care and Feeding of Discs 418<br />

Handling and Storage 418<br />

Cleaning and Repairing <strong>DVD</strong>s 419<br />

To Buy or Not to Buy 420<br />

Extol the Virtues 420<br />

Beware of Bamboozling 422<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> Is to Videotape What CD Is to Cassette Tape 423<br />

Think of It as a CD Player That Plays Movies 423<br />

The Computer Connection 423<br />

On the Other Hand 424<br />

The <strong>DVD</strong>-Video Buying Decision Quiz 424<br />

Chapter 10 <strong>DVD</strong> in Business and Education 431<br />

Introduction 432<br />

The Appeal of <strong>DVD</strong> 432<br />

The Appeal of <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 434<br />

The Appeal of <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM 436<br />

Sales and Marketing 437<br />

Communications 438<br />

Training and Business Education 439<br />

Industrial Applications 440<br />

Classroom Education 441<br />

Chapter 11 <strong>DVD</strong> on Computers 443<br />

Introduction 444<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video Sets the Standard 444<br />

Multimedia: Out of the Frying Pan ... 445<br />

A Slow Start 446<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-ROM for Computers 447<br />

Features 448<br />

Compatibility 448<br />

Interface 449<br />

Disk Format and I/O Drivers 450<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video for Computers 452<br />

The <strong>DVD</strong>-Video Computer 453<br />

Hardware <strong>DVD</strong>-Video Playback 453<br />

Software <strong>DVD</strong>-Video Playback 454

xvi<br />

Contents<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video Drivers 455<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video Details 459<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> By Any Other Name: Application Types 460<br />

Pure <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 460<br />

Computer Bonus <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 461<br />

Computer-augmented <strong>DVD</strong>-Video 462<br />

Split <strong>DVD</strong>-Video/<strong>DVD</strong>-ROM 462<br />

Multimedia <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM 462<br />

Data Storage <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM 463<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> Production Levels 463<br />

Web<strong>DVD</strong> 465<br />

Web<strong>DVD</strong> Applications 469<br />

Enabling Web<strong>DVD</strong> 471<br />

Creating Web<strong>DVD</strong> 473<br />

Web<strong>DVD</strong> for Windows 477<br />

Web<strong>DVD</strong> for Macintosh 478<br />

Web<strong>DVD</strong> for All Platforms 478<br />

Why Not Web<strong>DVD</strong>? 479<br />

Why Web<strong>DVD</strong>? 480<br />

Copy Protection Details 481<br />

Content-Scrambling System (CSS) 481<br />

Content Protection for Prerecorded Media (CPPM) 488<br />

Content Protection for Recordable Media (CPRM) 489<br />

HDCP 490<br />

Region Management Details 491<br />

Chapter 12 Essentials of <strong>DVD</strong> Production 493<br />

Introduction 494<br />

General <strong>DVD</strong> Production 494<br />

Project Examples 495<br />

CD or <strong>DVD</strong>? 495<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-5 or <strong>DVD</strong>-9 or <strong>DVD</strong>-10? 495<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video or <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM or Both? 496<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video and <strong>DVD</strong>-Audio Production 497<br />

Tasks and Skills 499<br />

The Production Process 500<br />

Production Decisions 501<br />

Multiregion and Multilanguage Issues 502<br />

Supplemental Material 504

Contents xvii<br />

Scheduling and Asset Management 505<br />

Project Design 506<br />

Menu Design 508<br />

Navigation Design 512<br />

Balancing the Bit Budget 515<br />

Asset Preparation 518<br />

Preparing Video Assets 518<br />

Preparing Animation and Composited Video 521<br />

Preparing Audio Assets 522<br />

Preparing Subpictures 525<br />

Preparing Graphics 527<br />

Putting It All Together (Authoring) 531<br />

Formatting and Output 533<br />

Testing and Quality Control 534<br />

Replication, Duplication, and Distribution 536<br />

Production Maxims 539<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-ROM Production 540<br />

File Systems and Filenames 540<br />

Bit Budgeting 541<br />

AV File Formats 542<br />

Hybrid Discs 543<br />

Chapter 13 The Future of <strong>DVD</strong> 545<br />

Introduction 546<br />

The Prediction Gallery 547<br />

New Generations of <strong>DVD</strong> 552<br />

The Death of VCRs 552<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> Players, Take 2 553<br />

Hybrid Systems 555<br />

HD-<strong>DVD</strong> 556<br />

No Laserdisc-Sized <strong>DVD</strong> 557<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> for Computer Multimedia 558<br />

Faster Sooner 558<br />

The Death of CD-ROM 559<br />

The Interregnum of CD-RW 559<br />

Standards, Anyone? 560<br />

Mr. Computer Goes to Hollywood 561<br />

The Changing Face of Home Entertainment 561<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> in the Classroom 563<br />

The Far Horizon 567

xviii<br />

Contents<br />

Appendix A Quick Reference 569<br />

Appendix B Standards Related to <strong>DVD</strong> 611<br />

Appendix C References and Information Sources 615<br />

Glossary 627<br />

Index 669

FOREWORD<br />

It may seem hard to believe, but more than three years have passed since<br />

the first edition of Jim Taylor’s <strong>DVD</strong> <strong>Demystified</strong> was written. In those<br />

dark, early days, few people knew much about <strong>DVD</strong>, and its future was<br />

by no means assured. At industry conferences, somber war stories about<br />

the challenges and high cost of producing theatrical <strong>DVD</strong> titles were presented.<br />

Promises of 17-GB <strong>DVD</strong>-18 discs seemed more like science fiction<br />

than reality. Predictions of home video <strong>DVD</strong> recorders entering the market<br />

seemed preposterous, since the equivalent technology required to<br />

author and record <strong>DVD</strong> programs cost more than $200,000 at the time.<br />

Several well-publicized compatibility problems existed between early<br />

players and titles, and there were real concerns about whether all of the<br />

major motion picture studios would ever commit to the format and release<br />

titles on <strong>DVD</strong>.<br />

These were shaky times for the format, and some cynics joked that<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> stood for “doubtful, very doubtful”. In early 1997, I stood in my company’s<br />

booth at an industry trade show trying to provide a simple description<br />

of <strong>DVD</strong> to groups of skeptical video producers and engineers. After<br />

my attempts to explain the format’s many complexities were greeted with<br />

quizzical looks, I began using a more succinct description: “<strong>DVD</strong> is movies<br />

on little discs.” Although many people, even the technical ones, were surprisingly<br />

satisfied with this desperate explanation, I remember worrying<br />

that if it was so difficult just to explain what <strong>DVD</strong> is, how would we ever<br />

sell it to actual users?<br />

Obviously, there was nothing to worry about.<br />

Today, chances are excellent that most of your neighbors know what<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is. Everywhere you look, evidence can be found of <strong>DVD</strong>’s astounding<br />

success: discount stores prominently display racks of video titles; brand<br />

name <strong>DVD</strong> players sell at low prices that were unthinkable not long ago;<br />

and some industry analysts now believe that home <strong>DVD</strong> video recorders<br />

will replace VCRs within a few years. Countless thousands of titles are<br />

available worldwide—some on 17-GB <strong>DVD</strong>-18 discs—and many more<br />

arrive every day. The format has in fact become so synonymous with high<br />

quality and value that many people happily buy movies on <strong>DVD</strong> that they<br />

already own on tape or laserdisc.<br />

In addition to its success in the consumer video business, a promising<br />

industrial market for <strong>DVD</strong> has also formed. Corporations, schools, hospitals,<br />

the military, and other government agencies have all put <strong>DVD</strong> to use<br />

for a variety of applications. That cool video you see playing on a videowall<br />

Copyright 2001 The McGraw-Hill Companies. Click Here for Terms of Use.

xx<br />

Foreword<br />

at the mall may in fact be coming from a <strong>DVD</strong> disc. Kids at a U.S. high<br />

school are learning about Newtonian physics from a detailed frame-byframe<br />

study of scenes in an action-adventure movie. Computer images of<br />

your heart might be stored in an automated <strong>DVD</strong> library system that is<br />

growing in a number of hospitals. Some military officers are now learning<br />

leadership skills through the use of interactive <strong>DVD</strong> training systems.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> has, without a doubt, hit the big time, and it’s clearly here to stay.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> has, of course, always been far more than just “movies on little<br />

discs.” It includes four physical formats: <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM, <strong>DVD</strong>-R, <strong>DVD</strong>-RAM,<br />

and <strong>DVD</strong>-RW. <strong>DVD</strong> also has three application formats: <strong>DVD</strong> Video, <strong>DVD</strong><br />

Audio Recording, and <strong>DVD</strong> Video Recording, with more on the way. The<br />

richness of these offerings, however, is a mixed bag of goods. Although<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> has a solution for just about any storage problem, making sense of<br />

it all is still a challenge. This, of course, is why this book was written.<br />

For the past three years, Jim Taylor’s <strong>DVD</strong> <strong>Demystified</strong> has become the<br />

authoritative bible of the industry, bar none. I am certain that every selfrespecting<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> professional in the business owns a well-worn, dog-eared<br />

copy. It’s a book that smart people never loan out because there’s a good<br />

chance it won’t be returned. Why? Because it is the most complete, userfriendly<br />

source of information available about this very complex format.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> <strong>Demystified</strong> is aimed at individuals who don’t enjoy reading the<br />

massive, arcane (and expensive) <strong>DVD</strong> specification books. In other words,<br />

this book targets just about everyone. In fact, I’ll let you in on a little<br />

secret. I know at least one person who does have access to the spec books<br />

and always reaches for Jim’s book first.<br />

The only thing that improves on <strong>DVD</strong> <strong>Demystified</strong> is...the updated<br />

version of <strong>DVD</strong> <strong>Demystified</strong>. As you can tell by now, the world of <strong>DVD</strong><br />

moves very fast, and no one follows the details as closely—and as accurately—as<br />

Jim Taylor. As in the first edition, you can count on an independent,<br />

thought-provoking analysis of all that is <strong>DVD</strong>, and you will find<br />

it written in an approachable style that both technical and non-technical<br />

readers will enjoy.<br />

So if you’re interested in <strong>DVD</strong> and haven’t bought this book yet, what<br />

are you waiting for? But a word from the wise: don’t let anyone borrow it.<br />

TEAMFLY<br />

ANDY PARSONS<br />

Senior Vice President<br />

Product Development & Technical Support<br />

Pioneer New Media Technologies

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

My heartfelt thanks to those who encouraged and supported me in writing<br />

this book. Both times.<br />

Many kind people spent time reading and commenting on drafts for the<br />

first edition and for this second edition: Kilroy Hughes, Ralph LaBarge,<br />

Dana Parker, Geoff Tully, Jerry Pierce, Steve Taylor, Robert Lundemo Aas,<br />

Chad Fogg, Roger Dressler, Tristan Savatier, Van Ling, Julia Taylor, Andy<br />

Parsons, and Leo Backman. This book is much richer because of them.<br />

Thanks also Bob Stuart, Tom Holman, Charles Poynton, Mike Schmit,<br />

Dave Schnuelle, the guys at Microsoft, and many others who took time to<br />

explain things. I’m also grateful to the <strong>DVD</strong> List members for sharing<br />

their knowledge, as well as to the denizens of the rec.video.dvd Internet<br />

newsgroups, the Home Theater Forum, and other Internet watering holes<br />

of <strong>DVD</strong> news and information.<br />

Extremely special thanks to Ari Zagnit and Mark Johnson for authoring<br />

the sample disc and to Samantha Cheng at TPS for making it happen.<br />

Thanks to Chuck Crawford and his wife for contributing their house<br />

to the project. I’m indebted to all the generous people who made the sample<br />

disc possible: Willie Chu for music; Laurie Smith for art; Thomas Bennett,<br />

ace Easter Frog hunter, Jamie Pickell for help with audio; Mark<br />

Waldrep at AIX Media Group; Ralph LaBarge at Alpha<strong>DVD</strong>; Richard<br />

Fortenberry at Atomboy; Scott Epstein at Broadcast <strong>DVD</strong>; Hideo<br />

Nagashima of Cinema Craft; Gene Radzik, Bill Barnes, and Roger<br />

Dressler at Dolby; Lorr Kramer, Patrick Watson, and Blake Welcher at<br />

DTS; David Goodman at <strong>DVD</strong> International; Gabe Murano at DVant;<br />

Bruce Nazarian at Gnome Digital; Henninger Media Services; Rey Umali<br />

and Brian Quandt at Heuris; Joe Kane at Joe Kane Productions and Van<br />

Ling at Lightstorm; Chris Brown, Cindy Halstead, Lenny Sharp, Todd<br />

Collart, and others at InterActual; Chinn Chin and Joe Monasterio at<br />

InterVideo; Michele Serra of Library <strong>DVD</strong>; Microsoft Studios and the Digital<br />

Video Services team, as well as Microsoft Windows Hardware Quality<br />

Lab (WHQL) and Microsoft Digital Media Division (specific thanks to<br />

Andrew Rosen, Craig Cleaver, Kenneth Smith, Randy James, and Eric<br />

Anderson); Fred Grossberg at Mill Reef Entertainment; Trai Forrester at<br />

New Constellation Technologies; Guy Kuo and Ovation Software; Garrett<br />

Smith at Paramount; Sandra Benedetto at Pioneer; Henry Steingieser,<br />

Gary Randles, and Randy Berg at Rainmaker New Media; Randy Glenn<br />

and Bob Michaels at Slingshot Entertainment; François Abbe at Snell &<br />

Wilcox; Paul Lefebvre and Mark Ely at Sonic Solutions; Tony Knight at<br />

SpinWare; Greg Wallace, Rainer Broderson, and Gary Hall at Spruce<br />

Copyright 2001 The McGraw-Hill Companies. Click Here for Terms of Use.

xxii<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

Technologies; Garrett Maki at Sunset Post; Charles Busslinger, Rick<br />

Deane, and Annie Chang at THX; Brad Collar at CVC; Shaun Taylor at<br />

Videodiscovery; Jim Babinski at WAMO; Gary Reber at Widescreen<br />

Review and Steve Michelson at Steve Michelson Productions; and Blaine<br />

Graboyes at Zuma Digital.<br />

Thanks to Steve Chapman at McGraw-Hill for backing me up and bailing<br />

me out, and to Beth Brown at MacPS for turning it all into something<br />

printable. And special thanks to Fleischman and Arthur, who have been<br />

solidly supportive.<br />

JIM TAYLOR

PREFACE<br />

To my surprise, the first edition of <strong>DVD</strong> <strong>Demystified</strong> quickly became the<br />

bible of the industry. I’m profoundly gratified that it has helped so many<br />

people understand <strong>DVD</strong> technology, and I appreciate everyone who has<br />

taken the time to send e-mail or tell me in person that they enjoyed the<br />

book.<br />

In spite of the publication of the <strong>DVD</strong> bible in late 1997, <strong>DVD</strong> technology<br />

refused to stand still. Unfinished variations such as writable <strong>DVD</strong><br />

and <strong>DVD</strong>-Audio became less unfinished, and new applications such as<br />

Web<strong>DVD</strong> and Divx reshaped markets and perceptions. So, in a brief<br />

moment of insanity, having forgotten what an enormous task it was to<br />

write this book in the first place, I agreed to do a second edition. If this<br />

new edition helps people better understand <strong>DVD</strong> and use its unique features<br />

to achieve their creative visions then my time will have been spent<br />

well.<br />

Copyright 2001 The McGraw-Hill Companies. Click Here for Terms of Use.

This page intentionally left blank.

CHAPTER<br />

1<br />

What Is <strong>DVD</strong>?<br />

Copyright 2001 The McGraw-Hill Companies. Click Here for Terms of Use.

2<br />

Introduction<br />

Chapter 1<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is the future. 1 No matter who you are or what you do, <strong>DVD</strong> technology<br />

will be in your future, supplying entertainment, information, and<br />

enlightenment in the form of video, audio, and computer data. <strong>DVD</strong> embodies<br />

the grand unification theory of entertainment and business media: If it<br />

fulfills the hopes of its creators, <strong>DVD</strong> will replace audio compact discs<br />

(CDs), videotapes, laserdiscs, CD-ROMs, video game cartridges, and even<br />

certain printed publications. By its third birthday, <strong>DVD</strong> had already become<br />

the most successful consumer electronics entertainment product of all time,<br />

with over 6 million players sold in the United States, over 10 million players<br />

worldwide, and over 30 million <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM computers.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is a bridge. According to the <strong>DVD</strong> Entertainment Group, <strong>DVD</strong><br />

is “the medium of the new millennium.” Although undoubtedly there will be<br />

more important media in the next thousand years, this is an accurate<br />

description for the first decade or so, since <strong>DVD</strong> is the ideal convergent<br />

medium for a converging world. We are witnessing watershed transitions<br />

from analog TV to digital TV (DTV), from interlaced video to progressive<br />

video, from standard TV to widescreen TV, and from passive entertainment<br />

to interactive entertainment. In every case <strong>DVD</strong> works on both sides, bridging<br />

from the “old way” to the “new way.”<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is excellence. In a world where the prevailing trend is to<br />

squeeze in more channels and longer playing time at the sacrifice of quality,<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is the standout contrarian. As broadcasters convert to DTV, they<br />

are more likely to use the extra space provided by digital compression to<br />

hold more channels of low quality rather than a few channels of high quality.<br />

Digital satellite providers already have taken this approach. Anyone<br />

hawking streaming video across the Internet has thrown aesthetics out<br />

the window. In contrast, most <strong>DVD</strong>s are created by people who care passionately<br />

about the video experience—people who spend months cleaning<br />

up video frame by frame, restoring and remixing audio, reassembling<br />

director’s cut versions, recording commentaries, researching outtakes and<br />

extras, and providing a richness and depth of content seldom seen in other<br />

media. <strong>DVD</strong> is not the ultimate in video quality, but it is the standard<br />

bearer for consumer entertainment.<br />

1 As Criswell solemnly intones at the beginning of the Plan 9 from Outer Space <strong>DVD</strong>, “We are all<br />

interested in the future, for that is where you and I are going to spend the rest of our lives. And<br />

remember, my friends, future events such as these will affect you in the future. You are interested<br />

in the unknown, the mysterious, the unexplainable. That is why you are here.”

What Is <strong>DVD</strong>?<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is just <strong>DVD</strong>. In the early days of <strong>DVD</strong>’s development, the letters<br />

stood for digital video disc. Later, like a stepsister trying to squish her ugly<br />

foot into a glass slipper, a few companies tried to retrofit the acronym to<br />

“digital versatile disc” in a harebrained attempt to express the versatility of<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>. But just as everyone knows what a VCR and a VHS tape are without<br />

worrying what the letters stand for, 2 <strong>DVD</strong> stands on it own.<br />

But what is <strong>DVD</strong>? Put simply, <strong>DVD</strong> is the next generation of CD technology.<br />

Improvements in optical technology have made the tightly packed<br />

microscopic pits that store data on an optical disc even more microscopic<br />

and even more tightly packed. A <strong>DVD</strong> is the same size as the familiar CD—<br />

12 centimeters wide (about 4.7 inches)—but it stores up to 25 times more<br />

and is more than nine times faster.<br />

And yet, <strong>DVD</strong> is much more than CD on steroids. Its increased storage<br />

capacity and speed allow it to accommodate high-quality digital video in<br />

MPEG-2 format. The result is a small, shiny disc that holds better-than-TV<br />

video and better-than-CD audio. A basic <strong>DVD</strong> can contain a movie over two<br />

hours long. A double-sided, dual-layer <strong>DVD</strong> can hold about eight hours of<br />

near-cinema-quality video or more than 30 hours of VHS-quality video. If<br />

only still pictures are used, <strong>DVD</strong> becomes an audio book that can play continuously<br />

for weeks.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> has many tricks to woo both the weary couch potato and the multimedia<br />

junkie alike, such as a widescreen picture, multichannel surround<br />

sound, multilingual audio tracks, selectable subtitles, multiple camera<br />

angles, karaoke features, seamless branching for multiple storylines, navigation<br />

menus, instant fast forward/rewind, and more.<br />

Just as audio CD has its computer counterpart in CD-ROM, <strong>DVD</strong> has<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-ROM, which goes far beyond CD-ROM. <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM holds from 4.4 to 16<br />

gigabytes of data—25 times as much as a 650-megabyte CD-ROM—and<br />

sends it to the computer faster than a comparable CD-ROM drive.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is inexpensive. The first few generations of <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM drives were<br />

more expensive than CD-ROM drives, but as the technology has improved<br />

and production quantities have increased, the price gap between them has<br />

continued to narrow. Once the price gap is insignificant, manufacturers will<br />

stop making CD-ROM drives. During the first few years, <strong>DVD</strong>-Video players<br />

were as expensive as high-end VCRs, but mass production of <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM<br />

drives and plummeting costs of audio/video decoder chips are driving the<br />

price of consumer <strong>DVD</strong> players down to the same level as VCRs and CD<br />

2 Some people claim VHS stands for video home system, whereas others insist it stands for video<br />

helical scan or vertical helical scan. Just as with <strong>DVD</strong>, it is better to ignore the fuzzy etymology.<br />

3

4<br />

players. <strong>DVD</strong> discs are produced with much of the same equipment used for<br />

CDs, and because they are stamped instead of recorded, they can be produced<br />

cheaper and faster than tapes.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is at the crest of a wave bringing significant change to the world of<br />

video entertainment and multimedia. It is the first high-quality interactive<br />

medium to be affordable to the mass market. Until now, the high-impact<br />

visuals of movies, television, and videotape have been linear and unchanging,<br />

whereas the dynamic and responsive environment of computer multimedia<br />

has suffered from unimpressively tiny video windows with fuzzy,<br />

jerky motion. Many artists with the vision to do extraordinary things with<br />

an interactive environment have shunned CD-ROM and computers<br />

because their creative standards would be compromised. As a result, they<br />

have been constricted to the straight and narrow of traditional linear video<br />

presentation designed to appeal to the lowest common interests. 3 This does<br />

not mean that <strong>DVD</strong> closes the door on beginning-to-end storytelling, only<br />

that it opens new doors for different approaches. <strong>DVD</strong> is a fresh digital canvas<br />

onto which artists can expand their abilities and sketch their nonlinear<br />

visions in time and space to be recreated on television screens and computer<br />

screens alike as a different experience for each participatory viewer.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video versus <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM<br />

Chapter 1<br />

NOTE: Just as CD audio is not the same as CD-ROM, <strong>DVD</strong>-Video is not<br />

the same as <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM.<br />

This book will tell you many things about <strong>DVD</strong>, but if you take away only a<br />

few tidbits, one of them should be that <strong>DVD</strong>-Video is not the same as <strong>DVD</strong>-<br />

ROM. Just as CD-ROM and CD audio are different applications of the same<br />

3 George Gilder pulls no punches when making this point in his book Life After Television: “TV<br />

defies the most obvious fact about its customers: their prodigal and efflorescent diversity. TV<br />

ignores the reality that people are not inherently couch potatoes; given a chance, they talk back<br />

and interact. People have little in common except their prurient interests and morbid fears and<br />

anxieties. Necessarily aiming its fare at this lowest-common-denominator target, television gets<br />

worse and worse every year.”

What Is <strong>DVD</strong>?<br />

technology, <strong>DVD</strong> is two separate things: (1) a computer data storage<br />

medium and (2) an audio/video storage medium. You use a <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM drive<br />

—like a CD-ROM drive—to read computer data from a <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM disc. You<br />

use a <strong>DVD</strong> player—like a VCR or a CD player—to play back video and<br />

audio from a <strong>DVD</strong> (more correctly called <strong>DVD</strong>-Video). As computers become<br />

true multimedia systems, this distinction is beginning to disappear, but it is<br />

still important to understand the difference.<br />

Technically, <strong>DVD</strong> is made up of a set of physical media specifications<br />

(read-only <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM, recordable <strong>DVD</strong>-R, rewritable <strong>DVD</strong>-RAM, etc.) and<br />

a set of application specifications (<strong>DVD</strong>-Video, <strong>DVD</strong>-Audio, and other possible<br />

specialized formats for applications such as videogame consoles).<br />

Unfortunately, the <strong>DVD</strong> family is plagued with sibling rivalry and competing<br />

formats. The compatibilities and incompatibilities of the physical and<br />

logical formats are a bewildering muddle.<br />

What Does <strong>DVD</strong> Portend?<br />

Motion video is one of the most deeply affecting creations of humankind. It<br />

combines the ethereal effects of sound and music, the realistic impact of<br />

photography, the engrossing drama of theatrical plays, and the variety of<br />

visual arts and weaves them all together with the ageless appeal of the storyteller.<br />

We are endlessly attempting to improve the richness of this<br />

medium with which we replay and reshape our impressions and visions of<br />

the world. <strong>DVD</strong> is one small step in this quest—but a very critical one. It is<br />

a milestone in the ascendancy of things digital.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is one of the final nails in the coffin of analog technology. Our depiction<br />

of the world is changing from analog forms such as vinyl records, film,<br />

and magnetic tape to digital forms such CDs, computer graphics, <strong>DVD</strong>s, and<br />

the Internet. The advantage of information in digital form is that it can be<br />

manipulated and processed easily by computer; it can be compressed to<br />

achieve cheaper and faster storage or transmission; it can be stored and<br />

duplicated without generational loss; its circuitry does not drift with heat or<br />

age; it can be kept separate from noise and distortion in the signal; and it<br />

can be transmitted over long distances without degrading. As the Internet<br />

becomes the dominant paradigm for the way we receive, send, and work<br />

with information, <strong>DVD</strong> will play a vital role. It will take many, many years<br />

before the Internet is able to easily carry the immense amounts of data<br />

needed for television and movies, interactive multimedia, and even virtual<br />

worlds. Until then, <strong>DVD</strong> is positioned to be the primary vehicle for deliver-<br />

5

6<br />

ing these information streams. And there will always be a need to archive<br />

information while keeping it quickly accessible. <strong>DVD</strong> and future generations<br />

of <strong>DVD</strong> fit the bill.<br />

Some people believe that <strong>DVD</strong> heralds the complete convergence of computers<br />

and entertainment media. They feel that a technology such as <strong>DVD</strong><br />

that works as well in the family room as in the office is another reason that<br />

the TV and the computer will merge into one. Perhaps. Or perhaps the computer<br />

will always be a separate entity with a separate purpose. How many<br />

people want to write in a word processor or work on a spreadsheet while sitting<br />

on the couch in front of the TV with a cordless keyboard on their lap—<br />

especially if the kids want to watch Animaniacs or play Ultra Mario<br />

instead? Whatever the case, it is inevitable that consumer electronics will<br />

gain more of the capabilities of computers, and computers will assimilate<br />

more of the features of televisions and stereo systems. The line is blurring,<br />

and <strong>DVD</strong> is rubbing a very big eraser across it. 4<br />

Who Needs to Know About <strong>DVD</strong>?<br />

The number of people who are feeling or will feel the effect of <strong>DVD</strong> is truly<br />

astonishing. A large part of this astonished multitude requires a working<br />

knowledge of <strong>DVD</strong>, including its capabilities, strengths, and limitations.<br />

This book provides most of this knowledge.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> will affect a remarkably diverse range of fields. A few are illustrated<br />

in the following pages.<br />

Movies<br />

TEAMFLY<br />

Chapter 1<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> has significantly raised the quality and enjoyability of home entertainment.<br />

According to the Consumer Electronics Association (CEA), there<br />

were over 19 million American homes with a home theater 5 system by the<br />

end of 1999. As <strong>DVD</strong> player prices drop, the players are becoming increasingly<br />

attractive as the central component of home theater systems and as<br />

4In this age of digital art, it is probably more appropriate to say that <strong>DVD</strong> is rubbing a very large<br />

smudge tool across the line.<br />

5 CEA defines a home theater system as a 25-inch or larger TV, hi-fi VCR or laserdisc player or<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> player, and a surround sound system with at least four speakers.

What Is <strong>DVD</strong>?<br />

replacements for aging CD players. <strong>DVD</strong> video recorders, as they steadily<br />

drop in price, will challenge VCRs for the spot next to the television.<br />

Music and Audio<br />

Because audio CD is well established and satisfies the needs of most music<br />

listeners, <strong>DVD</strong> will have less of an effect in this area. The introduction of<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Audio trailed <strong>DVD</strong>-Video by almost 4 years, and the <strong>DVD</strong>-Video format<br />

already incorporated higher-than-CD-quality audio and multichannel<br />

surround sound. <strong>DVD</strong> players also play audio CDs. All this leaves the <strong>DVD</strong>-<br />

Audio format with a tough sales job. However, the unprecedented success of<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video ensures that <strong>DVD</strong>-Audio will come along for the ride, especially<br />

as new players support both formats and the distinctions fade away.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Audio has a special appeal to music labels because it includes copy<br />

protection features that CD never had. Whether those protections will last<br />

long and whether they continue to be relevant in the face of Internet music<br />

distribution remains to be seen.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is a boon for audio books and other spoken-word programs. Dozens<br />

of hours of stereo audio can be stored on one side of a single disc—a disc<br />

that is cheaper to produce and more convenient to use than cassette tapes<br />

or multi-CD sets.<br />

Music Performance Video<br />

Despite the success of MTV and the virtual prerequisite that a music group<br />

cut a video in order to be heard, music performance video has not done as<br />

well as expected in the videotape or laserdisc markets. Perhaps it is because<br />

you cannot pop a video in a player and continue to read or work around the<br />

house. The added versatility of <strong>DVD</strong>, however, may be the golden key that<br />

unlocks the gates for music performance video. With high-quality, longplaying<br />

video and multichannel surround sound, <strong>DVD</strong> music video appeals<br />

to a range of fans from opera to ballet to New Age to acid rock. Music<br />

albums on <strong>DVD</strong> can improve their fan appeal by adding such tidbits as live<br />

performances, interviews, backstage footage, outtakes, video liner notes,<br />

musician biographies, and documentaries. Sales of <strong>DVD</strong>-Video music titles<br />

have already exceeded many expectations.<br />

One of the targets for <strong>DVD</strong>-Video player sales is the replacement CD<br />

player market. CD players inevitably break or are upgraded, and shoppers<br />

looking for a new player may be persuaded to spend a little more to get a<br />

7

8<br />

device that also can play movies. The natural convergence of the audio and<br />

video player will bolster the success of combined music and video titles.<br />

Training and Productivity<br />

Until it is eventually replaced by streaming video on broadband Internet,<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> will become the medium of choice for video training. The low cost of<br />

hardware and discs, the widespread use of players, the availability of<br />

authoring systems, and a profusion of knowledgeable <strong>DVD</strong> developers and<br />

producers will make <strong>DVD</strong>—in both <strong>DVD</strong>-Video and multimedia <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM<br />

form—ideal for industrial training, teacher training, sales presentations,<br />

home education, and any other application where full video and audio are<br />

needed for effective instruction. Especially popular are <strong>DVD</strong>s that connect<br />

to the Internet, making up for the fact that streaming video is too small, too<br />

slow, too fuzzy, and too unreliable to be of any use to the average learner.<br />

Videos for teaching skills from accounting to TV repair to dental hygiene,<br />

from tai chi to guitar playing to flower arranging become vastly more effective<br />

when they take advantage of the on-screen menus, detailed images,<br />

multiple soundtracks, selectable subtitles, and other advanced interactive<br />

features of <strong>DVD</strong>. Consider an exercise video that randomly selects different<br />

routines each day or lets you choose the mood, the tempo, and the muscle<br />

groups on which to focus. Or a first-aid training course that slowly increases<br />

the difficulty level of the lessons and the complexity of the practice sessions.<br />

Or an auto-mechanic training video that allows you to view a procedure<br />

from different angles at the touch of a remote control (preferably one with<br />

a grease-proof cover). Or a cookbook that helps you select recipes via menus<br />

and indexes and then demonstrates with a skilled chef leading you through<br />

every step of the preparation. All this on a small disc that never wears out<br />

and never has to be rewound or fast-forwarded.<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is cheaper and easier to produce, store, and distribute than videotape.<br />

Other products such as laserdisc, CD-i, and even Video CD have done<br />

well in training applications, but they require expensive or specialized players.<br />

As <strong>DVD</strong> becomes more established, almost every home and office will<br />

have either a standalone player or a <strong>DVD</strong> computer.<br />

Education<br />

Chapter 1<br />

Filmstrips, 16-mm films, VHS tapes, laserdiscs, CD-i discs, Video CDs, CD-<br />

ROMs, and the Internet have all had roles in providing images and sound

What Is <strong>DVD</strong>?<br />

to supplement textbooks and teachers. Most newer technologies lack the<br />

picture quality and clarity that is so important for classroom presentations.<br />

The exceptional image detail, high storage capacity, and low cost of <strong>DVD</strong><br />

make it an excellent candidate for use in classrooms, especially since it integrates<br />

well with computers. Even though <strong>DVD</strong>-Video players may not be<br />

widely adopted in education, <strong>DVD</strong> computers will be. CD-ROM has infiltrated<br />

all levels of schooling from home to kindergarten to college and will<br />

soon pass the baton to <strong>DVD</strong> as new computers with built-in <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM<br />

drives are purchased. Educational publishers will discover how to make<br />

the most of <strong>DVD</strong>, creating truly interactive applications with the sensory<br />

impact and realism needed to stimulate and inspire inquisitive minds.<br />

Computer Software<br />

CD-ROM has become the computer software distribution medium of choice.<br />

To reduce manufacturing costs, most software companies use CD-ROMs<br />

rather than expensive and unwieldy piles of floppy disks. Yet some applications<br />

are too large even for the multimegabyte capacity of CD-ROM. These<br />

include large application suites, clip art collections, software libraries containing<br />

dozens of programs that can be unlocked by paying a fee and receiving<br />

a special code, specialized databases with hundreds of millions of<br />

entries, and massive software products such as network operating systems<br />

and document collections. Phone books that used to fill six or more CD-<br />

ROMs now fit onto a single <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM. Companies that distribute monthly<br />

updates of CD-ROM sets can ship free <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM drives to their customers<br />

and pay for them within a year with the savings on production costs alone.<br />

Computer Multimedia<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-ROM products have been slow to appear, largely because the multimedia<br />

CD-ROM market is so tough. CD-ROM publishers struggling to produce<br />

a product within budget, convince distributors to carry it, and get it onto limited<br />

shelf space are reluctant to complicate their lives with a new format.<br />

Still, many multimedia producers are stifled by the narrow confines of<br />

CD-ROM and yearn for the wide open spaces and liberating speed of <strong>DVD</strong>-<br />

ROM. Microsoft’s Encarta encyclopedia has overflowed onto more than one<br />

CD-ROM but can expand for years to come without filling up its single<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-ROM. The National Geographic collection that is spread across 31<br />

CD-ROMs is much more usable on 4 <strong>DVD</strong>-ROMs.<br />

9

10<br />

In addition to space for more data, <strong>DVD</strong> brings along high-quality audio<br />

and video. Many new computers have hardware or software decoders that<br />

can be used to play <strong>DVD</strong> movies. These <strong>DVD</strong>-enabled computers will be<br />

even more effective for realistic simulations, games, education, and “edutainment.”<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> eventually will make blocky, quarter-screen computer<br />

video a distant, dismal memory.<br />

Video Games<br />

The capacity to add high-quality, real-life video and full surround sound to<br />

three-dimensional game graphics is attractive to video game manufacturers.<br />

The major game console manufacturers, Nintendo, Sega, and<br />

Sony—and Microsoft with its Xbox—are all using <strong>DVD</strong> in the newest versions<br />

of their systems. A combination video game/CD/<strong>DVD</strong> player is very<br />

appealing.<br />

Many past attempts to combine video footage with interactive games<br />

have been met with yawns, but the technology will improve until it finally<br />

clicks. Video games that make extensive use of full-screen video—even multimedia<br />

games traditionally available only for computers—are appearing in<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video editions that play on any home <strong>DVD</strong> player and on <strong>DVD</strong> computers.<br />

For example, the venerable Dragon’s Lair, a groundbreaking arcade<br />

video game that used a laserdisc for movie-quality animation, is now available<br />

on <strong>DVD</strong>-Video.<br />

Information Publishing<br />

Chapter 1<br />

The Internet is a wonderfully effective and efficient medium for information<br />

publishing, but it lacks the bandwidth needed to do justice to large<br />

amounts of data rich with graphics, audio, and motion video. <strong>DVD</strong>, with<br />

storage capacity far surpassing CD-ROM plus standardized formats for<br />

audio and video, is perfect for publishing and distributing information in<br />

our ever more knowledge-intensive and information-hungry world.<br />

Organizations can use <strong>DVD</strong>-Video and <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM to quickly and easily<br />

disseminate reports, training material, manuals, detailed reference handbooks,<br />

document archives, and much more. Portable document formats such<br />

as Adobe Acrobat and HTML are perfectly suited to publishing text and pictures<br />

on <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM. Recordable <strong>DVD</strong> soon will be available and affordable<br />

for custom publishing of discs created on the desktop.

What Is <strong>DVD</strong>?<br />

Marketing and Communications<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video and <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM are well suited to carry information from businesses<br />

to their customers and from businesses to businesses. A <strong>DVD</strong> can<br />

hold an exhaustive catalog able to elaborate on each product with full-color<br />

illustrations, video clips, demonstrations, customer testimonials, and more<br />

at a fraction of the cost of printed catalogs. Bulky, inconvenient videotapes<br />

of product information can be replaced with thin discs containing on-screen<br />

menus that guide the viewer on how to use the product, with easy and<br />

instant access to any section of the disc.<br />

The storage capacity of <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM can be exploited to put entire software<br />

product lines on a single disc that can be sent out to thousands or millions<br />

of prospective customers in inexpensive mailings. The disc can include<br />

demo versions of each product, with protected versions of the full product<br />

that can be unlocked by placing an order over the phone or the Internet.<br />

And More . . .<br />

11<br />

■ Picture archives. Photo collections, clip art, and clip media have<br />

long since exceeded the capacity of CD-ROM. <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM allows more<br />

content or higher quality or both. As recordable <strong>DVD</strong> becomes<br />

affordable and easy to use, it also will enable personal media<br />

publishing. Anyone with a digital camera, some video editing software,<br />

and a recordable <strong>DVD</strong> drive can put pictures and home movies on a<br />

disc to send to friends and relatives who have a <strong>DVD</strong> player or a <strong>DVD</strong><br />

computer.<br />

■ Set-top boxes, digital receivers, and personal video recorders.<br />

Savvy designers are already at work combining <strong>DVD</strong> players with the<br />

boxes used for interactive TV, digital satellite, digital cable, hard-disk—<br />

based video recorders, and other digital video applications. All these<br />

systems are based on the same underlying digital compression<br />

technology and can benefit from shared components.<br />

■ Web<strong>DVD</strong>. Many announcements have been made of products<br />

combining the multimedia capabilities of <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM and <strong>DVD</strong>-Video<br />

with the timeliness and interactivity of the Internet. Data-intensive<br />

media such as audio, video, and even large databases simply do not travel<br />

well over the Internet. Since broadband Internet will not arrive anytime<br />

soon, <strong>DVD</strong> is a perfect candidate to deliver the lion’s share of the content.

12<br />

■ Home productivity and “edutainment.” <strong>DVD</strong> covers the gamut<br />

from PlayStation to WebTV to home PC. <strong>DVD</strong>-Video can be used for<br />

reference products such as visual encyclopedias, fact books, and<br />

travelogues; training material such as music tutorials, arts and crafts<br />

lessons, and home improvement series; and education products such as<br />

documentaries, historical recreations, nature films, and more, all with<br />

accompanying text, photos, sidebars, quizzes, and so on.<br />

About This Book<br />

Chapter 1<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> <strong>Demystified</strong> is an introduction and reference for anyone who wants to<br />

understand <strong>DVD</strong>. It is not a production guide, nor is it a detailed technical<br />

handbook, but it provides an extensive technical grounding for anyone<br />

interested in <strong>DVD</strong>. This second edition is completely revised and expanded<br />

from the first edition.<br />

Chapter 2, “The World Before and After <strong>DVD</strong>,” provides historical context<br />

and background. Any top analyst or business leader will tell you that<br />

extrapolating from prior technologies is the best way to predict technology<br />

trends. This chapter takes a historical stroll through the developments<br />

leading up to <strong>DVD</strong> and the first few years after its birth.<br />

Chapter 3, “<strong>DVD</strong> Technology Primer,” explains concepts such as aspect<br />

ratios, digital compression, and progressive scan. This chapter is a gentle<br />

technical introduction for nontechnical readers, but it should be useful for<br />

technical readers as well.<br />

Chapter 4, “<strong>DVD</strong> Overview,” covers the basic features of <strong>DVD</strong>, particularly<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>-Video, as well as topics such as compatibility, regional management,<br />

copy protection, and licensing. It also includes a section on myths and<br />

misunderstood characteristics of <strong>DVD</strong>.<br />

Chapter 5, “Disc and Data Details,” delves deeper into the viscera of<br />

<strong>DVD</strong>, examining physical structures, disc production, file formats, and<br />

other low-level details. This chapter is not essential to understanding or<br />

using <strong>DVD</strong>, but should be instructive for anyone desiring a strong grasp of<br />

the underpinnings.<br />

Chapter 6, “Application Details—<strong>DVD</strong>-Video and <strong>DVD</strong>-Audio,” reveals<br />

the particulars of the video and audio specifications for <strong>DVD</strong>. It lays out the<br />

data structures, stream composition, navigation information, and other elements<br />

of the <strong>DVD</strong> application formats.<br />

Chapter 7, “What’s Wrong with <strong>DVD</strong>,” explores the shortcomings of <strong>DVD</strong><br />

and how these might be overcome as the technology develops.

What Is <strong>DVD</strong>?<br />

Chapter 8, “<strong>DVD</strong> Comparison,” examines the relationships between <strong>DVD</strong><br />

and other consumer electronics technologies and computer storage media,<br />

including advantages and disadvantages of each, plus discussions of compatibility<br />

and interoperability.<br />

Chapter 9, “<strong>DVD</strong> at Home,” helps you decide if <strong>DVD</strong> is for you, gives<br />

advice on selecting a player, and describes how a <strong>DVD</strong> player connects into<br />

a home theater or stereo system.<br />

Chapter 10, “<strong>DVD</strong> in Business and Education,” discusses how <strong>DVD</strong><br />

applies to these areas, how it can be used best, and what effect it may have.<br />

Chapter 11, “<strong>DVD</strong> on Computers,” clarifies the variety of ways <strong>DVD</strong> can<br />

be used with computers. It also explains how to create <strong>DVD</strong>-Video discs<br />

that are enhanced for use on computers.<br />

Chapter 12, “Essentials of <strong>DVD</strong> Production,” entirely new for this second<br />

edition, dips into many of the mysteries of producing content for <strong>DVD</strong>-Video<br />

and <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM. This chapter provides a thorough grounding for anyone<br />

interested in creating <strong>DVD</strong>s or simply learning more about how <strong>DVD</strong>s are<br />

created.<br />

The last chapter, “The Future of <strong>DVD</strong>,” is a quick peek into the crystal ball<br />

to see what possibilities lie ahead for <strong>DVD</strong> and the world of digital video.<br />

Units and Notation<br />

<strong>DVD</strong> is a casualty of an unfortunate collision between the conventions of<br />

computer storage measurement and the norms of data communications<br />

measurement. The SI 6 abbreviations of k (thousands), M (millions), and G<br />

(billions) usually take on slightly different meanings when applied to bytes,<br />

in which case they are based on powers of 2 instead of powers of 10 (see<br />

Table 1.1).<br />

NOTE: In the world of <strong>DVD</strong>, a gigabyte is not always a gigabyte.<br />

13<br />

6Système International d’Unités—the international standard of measurement notations such as<br />

millimeters and kilograms.

14<br />

TABLE 1.1<br />

Meanings of<br />

Prefixes<br />

SI IEC IEC Common Computer<br />

Chapter 1<br />

Abbreviation Prefix Prefix Abbr. Use Use Difference<br />

k or K kilo kibi Ki 1000 (10 3 ) [k] 1024 (2 10 ) [K] 2.4%<br />

M mega mebi Mi 1,000,000 (10 6 ) 1,048,576 (2 20 ) 4.9%<br />

G giga gibi Gi 1,000,000,000 (10 9 ) 1,073,741,824 (2 30 ) 7.4%<br />

T tera tebi Ti 1,000,000,000,000 (10 12 ) 1,099,511,627,776 (2 40 ) 10%<br />

The problem is that there are no universal standards for unambiguous<br />

use of these prefixes. One person’s 4.7 GB is another person’s 4.38 GB, and<br />

one person’s 1.321 MB/s is another’s 1.385 MB/s. Can you tell which is<br />

which? 7<br />

The laziness of many engineers who mix notations such as KB/s, kb/s,<br />

and kbps with no clear distinction and no definition compounds the problem.<br />

And since divisions of 1000 look bigger than divisions of 1024, marketing<br />

mavens are much happier telling you that a dual-layer <strong>DVD</strong> holds<br />

8.5 gigabytes rather than a mere 7.9 gigabytes. It may seem trivial, but at<br />

larger denominations the difference between the two usages—and the<br />

resulting potential error—becomes significant. There is almost a 5 percent<br />

difference at the mega- level and over a 7 percent difference at the gigalevel.<br />

If you are planning to produce a <strong>DVD</strong> and you take pains to make<br />

sure your data takes, up just under 4.7 gigabytes (as reported by the operating<br />

system), you will be surprised and annoyed to discover that only 4.37<br />

gigabytes fit on the disc. Things will get worse down the road with a 10 percent<br />

difference at the tera- level.<br />

Since computer memory and data storage, including that of <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM<br />

and CD-ROM, usually are measured in megabytes and gigabytes (as<br />

opposed to millions of bytes and billions of bytes), this book uses 1024 as the<br />

basis for measurements of data size and data capacity, with abbreviations<br />

of KB, MB, and GB. However, since these abbreviations have become so<br />

7 The first (4.7 GB) is the typical data capacity given for <strong>DVD</strong>: 4.7 billion bytes, measured in magnitudes<br />

of 1000. The second (4.38 GB) is the “true” data capacity of <strong>DVD</strong>: 4.38 gigabytes, measured<br />

using the conventional computing method in magnitudes of 1024. The third (1.321 MB/s)<br />

is the reference data transfer rate of <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM measured in computer units of 1024 bytes per<br />

second. The fourth (1.385 MB/s) is <strong>DVD</strong>-ROM data transfer rate in thousands of bytes per second.<br />

If you do not know what any of this means, don’t worry—by Chapter 4 it should all make<br />

sense.

What Is <strong>DVD</strong>?<br />

15<br />

ambiguous, the term is spelled out when practical. In cases where it is necessary<br />

to be consistent with published numbers based on the alternative<br />

usage, the words thousand, million, and billion are used, or the abbreviations<br />

k bytes, M bytes, and G bytes are used (note the small k and the<br />

spaces).<br />

To distinguish kilobytes (1024 bytes) from other units such as kilometers<br />

(1000 meters), common practice is to use a large K for binary multiples.<br />

Unfortunately, other abbreviations such as M (mega) and m (micro) are<br />

already differentiated by case, so the convention cannot be applied uniformly<br />

to binary data storage. And in any case, too few people pay attention<br />

to these nuances.<br />

In 1999, the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) produced<br />

new prefixes for binary multiples 8 (see Table 1.1). Although the new prefixes<br />

may never catch on, or they may cause even more confusion, they are<br />

a valiant effort to solve the problem. The main strike against them is that<br />

they sound a bit silly. For example, the prefix for the new term gigabinary<br />

is gibi-, so a <strong>DVD</strong> can be said to hold 4.37 gibibytes, or GiB. The prefix for<br />

kilobinary is kibi-, and the prefix for terabinary is tebi-, yielding kibibytes<br />

and tebibytes. Jokes about “kibbles and bits” and “teletebis” are inevitable.<br />