Chapter 5-4: Tardigrades: Species Relationships - Bryophyte Ecology

Chapter 5-4: Tardigrades: Species Relationships - Bryophyte Ecology

Chapter 5-4: Tardigrades: Species Relationships - Bryophyte Ecology

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CHAPTER 5-4<br />

TARDIGRADES: SPECIES<br />

RELATIONSHIPS<br />

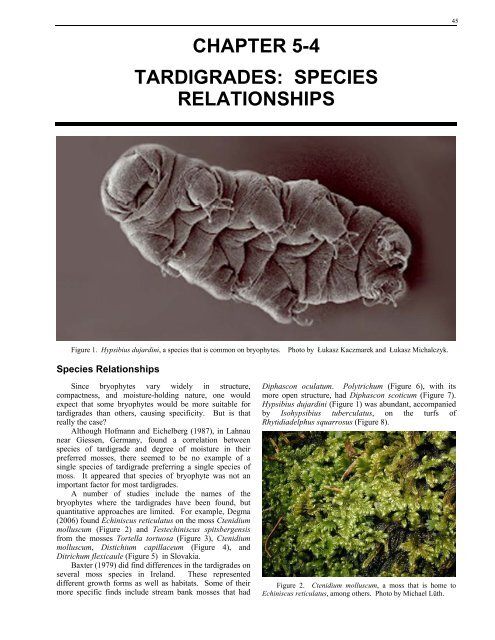

Figure 1. Hypsibius dujardini, a species that is common on bryophytes. Photo by Łukasz Kaczmarek and Łukasz Michalczyk.<br />

<strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong><br />

Since bryophytes vary widely in structure,<br />

compactness, and moisture-holding nature, one would<br />

expect that some bryophytes would be more suitable for<br />

tardigrades than others, causing specificity. But is that<br />

really the case?<br />

Although Hofmann and Eichelberg (1987), in Lahnau<br />

near Giessen, Germany, found a correlation between<br />

species of tardigrade and degree of moisture in their<br />

preferred mosses, there seemed to be no example of a<br />

single species of tardigrade preferring a single species of<br />

moss. It appeared that species of bryophyte was not an<br />

important factor for most tardigrades.<br />

A number of studies include the names of the<br />

bryophytes where the tardigrades have been found, but<br />

quantitative approaches are limited. For example, Degma<br />

(2006) found Echiniscus reticulatus on the moss Ctenidium<br />

molluscum (Figure 2) and Testechiniscus spitsbergensis<br />

from the mosses Tortella tortuosa (Figure 3), Ctenidium<br />

molluscum, Distichium capillaceum (Figure 4), and<br />

Ditrichum flexicaule (Figure 5) in Slovakia.<br />

Baxter (1979) did find differences in the tardigrades on<br />

several moss species in Ireland. These represented<br />

different growth forms as well as habitats. Some of their<br />

more specific finds include stream bank mosses that had<br />

Diphascon oculatum. Polytrichum (Figure 6), with its<br />

more open structure, had Diphascon scoticum (Figure 7).<br />

Hypsibius dujardini (Figure 1) was abundant, accompanied<br />

by Isohypsibius tuberculatus, on the turfs of<br />

Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus (Figure 8).<br />

Figure 2. Ctenidium molluscum, a moss that is home to<br />

Echiniscus reticulatus, among others. Photo by Michael Lüth.<br />

45

46 <strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong><br />

Figure 3. Tortella tortuosa, a Slovakian habitat for<br />

Testechiniscus spitsbergensis. Photo by Michael Lüth.<br />

Figure 4. Distichium capillaceum, a known tardigrade<br />

habitat. Photo by Michael Lüth.<br />

Figure 5. Ditrichum flexicaule, a habitat for Testechiniscus<br />

spitsbergensis. Photos by Michael Lüth.<br />

Figure 6. Polytrichum, a moss with spreading leaves that<br />

provide limited tardigrade habitat. Photo by Michael Lüth.<br />

Figure 7. Diphascon scoticum, a tardigrade that is able to<br />

inhabit Polytrichum. Photo by Paul Bartels.<br />

Figure 8. Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus, where Baxter (1979)<br />

found Isohypsibius tuberculatus and Diphascon scoticum. Photo<br />

by Michael Lüth.<br />

Horning et al. (1978) examined the tardigrades on 21<br />

species of mosses in New Zealand and listed the tardigrade<br />

species on each (Table 1). Some moss species clearly had<br />

more tardigrade species than others, ranging from 1 on<br />

Syntrichia rubra to 17 on Hypnum cupressiforme (Figure<br />

9). Limbophyllum divulsulum had 16 species.

<strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong> 47<br />

Table<br />

1. Tardigrade species found on the most common moss taxa in New Zealand. From Horning et al. 1978.<br />

Breutelia elongata Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Minibiotus intermedius<br />

Breutelia pendula Diphascon prorsirostre<br />

Diphascon scoticum<br />

Doryphoribius zyxiglobus<br />

Hypechiniscus exarmatus<br />

Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Bryum campylothecium Hypsibius convergens<br />

Isohypsibius sattleri<br />

Minibiotus intermedius<br />

Bryum dichotomum Hypsibius wilsoni<br />

Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Bryum truncorum Diphascon chilenense<br />

Diphascon scoticum<br />

Isohypsibius sattleri<br />

Isohypsibius wilsoni<br />

Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Macrobiotus recens<br />

Paramacrobiotus areolatus<br />

Paramacrobiotus richtersi<br />

Ramazzottius oberhaeuseri<br />

Dicranoloma billardieri Hypechiniscus exarmatus<br />

Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Dicranoloma grossialare Diphascon prorsirostre<br />

Hypechiniscus exarmatus<br />

Hypsibius dujardini<br />

Isohypsibius cameruni<br />

Isohypsibius sattleri<br />

Limmenius porcellus<br />

Macrobiotus anderssoni<br />

Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae<br />

Dicranoloma menziesii Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Paramacrobiotus areolatus<br />

Dicranoloma robustum Echiniscus bigranulatus<br />

Macrobiotus anderssoni<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Pseudechiniscus suillus<br />

Dicranoloma trichopodum Echiniscus quadrispinosus<br />

Echiniscus q. brachyspinosus<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Pseudechiniscus lateromamillatus<br />

Hypnum cupressiforme Diphascon alpinum<br />

Diphascon bullatum<br />

Echiniscus quadrispinosus<br />

Echiniscus spiniger<br />

Hypsibius dujardini<br />

Macrobiotus anderssoni<br />

Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Macrobiotus recens<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Oreella mollis<br />

Paramacrobiotus areolatus<br />

Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae<br />

Pseudechiniscus suillus<br />

Ramazzottius oberhaeuseri<br />

Lembophyllum divulsum Diphascon alpinum<br />

Doryphoribius zyxiglobus<br />

Hypsibius convergens<br />

Isohypsibius sattleri<br />

Macrobiotus anderssoni<br />

Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Macrobiotus recens<br />

Macrobiotus subjulietae<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Minibiotus intermedius<br />

Paramacrobiotus areolatus<br />

Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae<br />

Pseudechiniscus suillus<br />

Macromitrium erosulum Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Pseudechiniscus suillus<br />

Macromitrium longipes Doryphoribius zyxiglobus<br />

Hypsibius convergens<br />

Macrobiotus recens<br />

Minibiotus intermedius<br />

Porotrichum ramulosum Diphascon alpinum<br />

Diphascon scoticum<br />

Doryphoribius zyxiglobus<br />

Echiniscus bigranulatus<br />

Hypsibius convergens<br />

Macrobiotus anderssoni<br />

Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Macrobiotus rawsoni<br />

Minibiotus aculeatus<br />

Pseudechiniscus lateromamillatus<br />

Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae<br />

Pseudechiniscus suillus<br />

Racomitrium crispulum Calohypsibius ornatus<br />

Diphascon alpinum<br />

Echiniscus quadrispinosus<br />

Echiniscus zetotrymus<br />

Hebesuncus conjungens<br />

Hypsibius convergens<br />

Isohypsibius wilsoni<br />

Macrobiotus anderssoni<br />

Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Macrobiotus orcadensis<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Oreella minor<br />

Paramacrobiotus areolatus<br />

Pseudechiniscus suillus<br />

Racomitrium lanuginosum Diphascon scoticum<br />

Echiniscus quadrispinosus brachyspinosus<br />

Echiniscus vinculus<br />

Hebesuncus conjungens<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Minibiotus intermedius<br />

Oreella mollis<br />

Pseudechiniscus suillus<br />

Racomitrium ptychophyllum Echiniscus quadrispinosus<br />

Echiniscus velaminis<br />

Hebesuncus conjungens<br />

Hypechiniscus exarmatus<br />

Hypsibius dujardini<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Minibiotus intermedius<br />

Oreella mollis<br />

Syntrichia princeps Hypsibius convergens<br />

Ramazzottius oberhaeuseri<br />

Isohypsibius wilsoni<br />

Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Macrobiotus recens<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae<br />

Syntrichia rubra Diphascon scoticum<br />

Tortula subulata var. serrulata Diphascon scoticum<br />

Paramacrobiotus areolatus

48 <strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong><br />

Figure 9. Hypnum cupressiforme, the moss with the most tardigrade species in the New Zealand study by Horning et al. (1978),<br />

shown here on rock and as a pendant epiphyte. Photos by Michael Lüth.<br />

Hopefully lists like the one provided by Horning et al.<br />

(1978) will eventually permit us to determine the<br />

characteristics that foster tardigrade diversity and<br />

abundance. Perhaps the moss Hypnum cupressiforme had<br />

the most tardigrade species among the mosses in New<br />

Zealand because of its own wide habitat range there.<br />

However, Degma et al. (2005) found that distribution of the<br />

number of tardigrade species on this moss in their Slovakia<br />

sites was random, as supported by a Chi-square goodness<br />

of fit test. Nevertheless, its ubiquitous nature on a wide<br />

range of habitats in New Zealand may account for the<br />

greater number of species of tardigrades on Hypnum<br />

cupressiforme in the New Zealand study.<br />

A different kind of vertical zonation occurs among<br />

tardigrades on trees. In the Great Smoky Mountains<br />

National Park, the number of tardigrade species among<br />

epiphytes at breast height was greater than the number of<br />

species found at the base (Bartels & Nelson 2006).<br />

In a study of 270 Chinese mosses in the Herbarium of<br />

the Missouri Botanical Garden, only 78 specimens,<br />

representing 10 locations, had tardigrades (Beasley &<br />

Miller 2007). These were represented by 12 species.<br />

Several additional species were found and may be new<br />

species, but more specimens are needed to make adequate<br />

determinations. In this study, the mosses were identified<br />

and I present the moss and fauna here to facilitate<br />

comparisons for persons looking for possible specificity in<br />

conjunction with other studies (Table 2).<br />

In their study of Chinese mosses Beasley and Miller<br />

(2007) found that Heterotardigrada (armored tardigrades)<br />

were better represented than were Eutardigrada<br />

(unarmored tardigrades), a factor the authors attribute to the<br />

xerophilic moss samples and the locality, which has hot,<br />

dry summers, very cold, dry winters, low summer rainfall,<br />

and high winds (Fullard 1968). The Heterotardigrada have<br />

armor, which may account for their ability to withstand the<br />

dry habitat. These tardigrades also have cephalic (head)<br />

appendages with a sensorial function, a character lacking in<br />

the Eutardigrada, but so far their function has not been<br />

related to a bryophyte habitat. Beasley and Miller (2007)<br />

found little specificity, but most of the mosses they<br />

examined were xerophytic and exhibited similar moisture<br />

requirements. They did find that Echiniscus testudo (see<br />

Figure 11) occurred on a wider variety of mosses than did<br />

other tardigrade species.<br />

Table 2. Distribution of tardigrades on specific mosses in<br />

Xinjiang Uygur Region, China, based on herbarium specimens.<br />

From Beasley & Miller 2007.<br />

tardigrade numb/samples moss<br />

Bryodelphax asiaticus 1/1 Pseudoleskeella catenulata<br />

Cornechiniscus holmeni 18/5 Grimmia tergestina<br />

Mnium laevinerve<br />

Schistidium sp.<br />

Echiniscus blumi 4/4 Abietinella abietina<br />

Schistidium sp.<br />

Echiniscus canadensis 82/7 Grimmia laevigata<br />

Grimmia ovalis<br />

Grimmia tergestina<br />

Echiniscus granulatus 8/3 Grimmia longirostris<br />

Schistidium trichodon<br />

Schistidium sp.<br />

Echiniscus testudo 11/4 Grimmia anodon<br />

Grimmia longirostris<br />

Grimmia tergestina<br />

Lescuraea incurvata<br />

Pseudoleskeella catenulata<br />

Schistidium sp.<br />

Echiniscus trisetosus 33/5 Abietinella abietina<br />

Grimmia ovalis<br />

Pseudoleskeella catenulata<br />

Macrobiotus mauccii 2/2 Schistidium sp.<br />

Milnesium asiaticum 10/4 Grimmia anodon<br />

Grimmia tergestina<br />

Grimmia ovalis<br />

Schistidium sp.<br />

Milnesium longiungue 4/2 Grimmia laevigata<br />

Grimmia ovalis<br />

Milnesium tardigradum 5/4 Grimmia tergestina<br />

Grimmia ovalis<br />

Orthotrichum sp.<br />

Paramacrobiotus alekseevi 5/4 Brachythecium albicans<br />

Schistidium sp.<br />

Figure 10. Macrobiotus hufelandi. Photo by Martin Mach.

Figure 11. Adult Echiniscus. Photo by Martin Mach.<br />

Kathman and Cross (1991) found that species of<br />

bryophyte had no influence on the distribution or<br />

abundance of tardigrades from five mountains on<br />

Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. Despite a<br />

lack of specificity among the tardigrades, 39 species<br />

inhabited these 37 species of mountain bryophytes,<br />

comprising 14,000 individuals. Several researchers<br />

contend that any terrestrial species of tardigrade can be<br />

found on any species of moss, given the "appropriate<br />

microhabitat conditions" (Bertrand 1975; Ramazzotti &<br />

Maucci 1983). If these tardigrade bryophyte specialists<br />

find no differences among the bryophytes, can we blame<br />

the ecologists for lumping all the bryophytes in their<br />

studies as well?<br />

On Roan Mountain in Tennessee and North Carolina,<br />

Nelson (1973, 1975) found no specificity among 21<br />

tardigrade species on 25 bryophyte species. Hunter (1977)<br />

in Montgomery County, Tennessee, and Romano et al.<br />

(2001) in Choccolocco Creek in Alabama, USA, again<br />

were unable to find any dependence of tardigrades upon a<br />

particular species of bryophyte in their collections. In fact,<br />

Kathman and Cross (1991) were unable to find any<br />

correlation with altitude or aspect throughout a span from<br />

150 to 1525 m. They concluded that it was the presence of<br />

bryophyte that determined tardigrade presence, not the<br />

species of bryophyte, altitude, or locality.<br />

In collections from Giessen, Germany, the most<br />

common tardigrade species, the cosmopolitan Macrobiotus<br />

hufelandi, (Figure 10) had no preference for any moss<br />

species (Hofmann 1987). But lack of influence of<br />

bryophyte species may not always be the case. Hofmann<br />

(1987) used a preference index to show that four out of<br />

sixteen tardigrades from Giessen had distinct preferences<br />

among five moss species and that they seemed to prefer<br />

cushion mosses over sheet mosses. Also contrasting with<br />

the above researchers, Bertolani (1983) found that there<br />

seemed to be a species relationship between tardigrades<br />

<strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong> 49<br />

and coastal dune mosses. It is possible that this is again<br />

related to moisture. The moisture relationship might also<br />

explain why mosses on rotten logs seem to have few<br />

tardigrades. Could it be that they are too wet for too long?<br />

Growth Forms<br />

There is some indication that species differences may<br />

exist, based on growth form. The bryophyte form can<br />

affect the moisture-holding capacity and rate of loss of<br />

moisture. The foregoing evidence suggests that the<br />

moisture-holding capacity of cushion mosses was probably<br />

a desirable trait in that habitat. On the other hand, Beasley<br />

(1990) found that more samples of clubmosses<br />

(Lycopodiaceae) (75%) had tardigrades than did mosses<br />

(46%) or liverworts (0%) in Gunnison County, Colorado.<br />

Jönsson (2003) compared the tardigrade fauna on<br />

mosses in a coniferous forest and those on mosses in an<br />

adjacent clearcut area in Southern Sweden. He found<br />

sixteen tardigrade species, with the cosmopolitan<br />

Macrobiotus hufelandi (Figure 10) being by far the most<br />

common. Wefts had more tardigrades than other mosses.<br />

The forest samples tended to have more species, as one<br />

might expect based on moisture relations.<br />

Kathman and Cross (1991) found that tardigrades from<br />

Vancouver Island were more common on weft-forming<br />

mosses than on turfs, suggesting that the thick carpets of<br />

the wefts were more favorable habitat than the thinly<br />

clustered turfs with their thick rhizoidal mats and attached<br />

soil. Contrasting with some of these findings, and the<br />

preference for cushion mosses in the study by Hofmann<br />

(1987), Diane Nelson (East Tennessee State University,<br />

Johnson City, pers. comm. in Kathman & Cross 1991)<br />

found no preference for sheet or cushion mosses in her<br />

Roan Mountain, Virginia, USA study. Rather, those<br />

tardigrades were more common in thin, scraggly mosses or<br />

in small tufts than in thick cushion mosses.<br />

Sayre and Brunson (1971) compared tardigrade fauna<br />

on mosses in 26 North American collections from a variety<br />

of habitats and substrata (Figure 12). They found that<br />

mosses of short stature in the Thuidiaceae (Figure 13) and<br />

Hypnaceae (Figure 14) had the highest frequencies of<br />

tardigrades. Other moss-dwellers were found in fewer<br />

numbers on members of the moss families Orthotrichaceae<br />

(epiphytic and rock-dwelling tufts; Figure 15),<br />

Leucobryaceae (cushions; Figure 16), Polytrichaceae (tall<br />

turfs; Figure 17), Plagiotheciaceae (low mats; Figure 18),<br />

and Mniaceae (mats & wefts; Figure 19).<br />

Collins and Bateman (2001), studying tardigrade fauna<br />

of bryophytes in Newfoundland, Canada, found that rate of<br />

desiccation of the mosses affected distribution of<br />

tardigrades, and this suggests that bryophyte species and<br />

growth forms that dehydrate quickly should have fewer<br />

individuals and probably different or fewer species than<br />

those that retain water longer (see <strong>Chapter</strong> 4-6). In<br />

different climate regimes, that rate will differ. This may<br />

explain a preference for cushions in some locations and not<br />

in others. Data are needed on humidity within the various<br />

growth forms of bryophytes, correlated with tardigrade<br />

densities, to try to explain why different growth forms<br />

seem to be preferred in different locations.

50 <strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong><br />

Figure 12. Relative frequency of tardigrades on bryophytes<br />

of various North American substrata. Redrawn from Sayre &<br />

Brunson 1971.<br />

Figure 13. Thuidium delicatulum (Thuidiaceae), a lowstature<br />

moss that is a good tardigrade habitat. Photo by Michael<br />

Lüth.<br />

Figure 14. Hypnum revolutum (Hypnaceae), representing a<br />

family that includes low-stature mosses that had among the<br />

highest frequencies of tardigrades in 26 North American<br />

collections (Sayre & Brunson 1971). Photo by Michael Lüth.<br />

Figure 15. Orthotrichum pulchellum, an epiphytic moss in<br />

the Orthotrichaceae. This family is among those with lower<br />

numbers of tardigrades in the North American study of Sayre &<br />

Brunson (1971) compared to families of mat-forming species.<br />

Photo by Michael Lüth.<br />

Figure 16. Leucobryum glaucum, a cushion moss in the<br />

Leucobryaceae. This family of mosses had lower numbers of<br />

tardigrades than those found in the mat-forming mosses in 26<br />

North American collections (Sayre & Brunson 1971). Photo by<br />

Michael Lüth.<br />

Figure 17. Polytrichum juniperinum, a moss in the<br />

Polytrichaceae. This family of mosses tends to have low numbers<br />

of tardigrades (Sayre & Brunson 1971). The tardigrades often<br />

nestle in the leaf bases where water evaporates more slowly.<br />

Photo by Michael Lüth.

Figure 18. Plagiothecium denticulatum, a low-growing soil<br />

moss in Plagiotheciaceae, a family with limited numbers of<br />

tardigrade dwellers (Sayre & Brunson 1971). The flattened<br />

growth habit provides few protective chambers, perhaps<br />

accounting for the lower numbers. Photo by Michael Lüth.<br />

Figure 19. Plagiomnium cuspidatum, a soil moss in the<br />

Mniaceae, a family with limited numbers of tardigrade dwellers<br />

(Sayre & Brunson 1971). The spreading nature of the vertical<br />

shoots and the flattened nature of the horizontal shoots would<br />

most likely not provide many protective chambers for the<br />

tardigrades. Photo by Michael Lüth.<br />

Liverworts<br />

I would expect liverworts, with their flat structure, to<br />

have at least some differences. But there seems to be a<br />

paucity of reports on liverworts. Hinton and Meyer (2009)<br />

found two species of tardigrades [Milnesium tardigradum<br />

(Figure 20) and Macrobiotus hibiscus], both also common<br />

among mosses, in samples of the liverwort Jungermannia<br />

sp.) (Figure 21).<br />

Liverworts may actually house some interesting<br />

differences as a result of their underleaves (Figure 22) and<br />

flattened growth form (Figure 23). In their New Zealand<br />

study, Horning et al. (1978) found that among the<br />

liverworts (Table 3), Porella elegantula (Figure 22) had the<br />

most species (16). The folds and underleaves of this genus<br />

form tiny capillary areas where water is held, perhaps<br />

accounting for the large number of species. Interestingly,<br />

the tardigrade Macrobiotus snaresensis occurred on several<br />

<strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong> 51<br />

liverwort species (4 Lophocolea species, Plagiochila<br />

deltoidea), but did not appear in any moss collections. Of<br />

150 liverwort samples (26 species), 27% had tardigrades,<br />

with a total of 16 species, mean of 2.8 species, range 1-9.<br />

In 107 samples of foliose lichens, 60.7% had tardigrades,<br />

mean 2.2 species, range 1-11.<br />

Figure 20. Milnesium tardigradum, an inhabitant of both<br />

mosses and liverworts. Photo by Björn Sohlenius, Swedish<br />

Museum of Natural History.<br />

Figure 21. The leafy liverwort Jungermannia sphaerocarpa,<br />

representing a genus from which tardigrades are known. Photo by<br />

Michael Lüth.<br />

Figure 22. Porella elegantula, showing the underleaves and<br />

folds that create numerous capillary spaces. Photo by Jan-Peter<br />

Frahm.

52 <strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong><br />

Table 3. <strong>Species</strong> of tardigrades found on 13 liverwort species in New Zealand and surrounding islands. From Horning et al. 1978.<br />

Liverwort <strong>Species</strong> Tardigrade <strong>Species</strong> Liverwort <strong>Species</strong> Tardigrade <strong>Species</strong><br />

Lophocolea innovata Macrobiotus snaresensis<br />

Lophocolea. minor Macrobiotus snaresensis<br />

Lophocolea. subporosa Macrobiotus snaresensis<br />

Lophocolea semiteres Diphascon chilenense<br />

Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Lophocolea subporosa: Diphascon scoticum<br />

Hypsibius dujardini<br />

Macrobiotus snaresensis<br />

Lophocolea sp. Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Metzgeria decipiens Echiniscus spiniger<br />

Isohypsibius sattleri<br />

Paramacrobiotus areolatus)<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Minibiotus intermedius<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Macrobiotus snaresensis<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae<br />

Metzgeria decrescens Diphascon scoticum<br />

Macrobiotus recens<br />

Macrobiotus snaresensis<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Plagiochila deltoidea Echiniscus bigranulatus<br />

Hypechiniscus exarmatus<br />

Hypsibius convergens<br />

Isohypsibius cameruni<br />

Figure 23. Underside of leafy liverwort with two<br />

tardigrades. Photo by Łukasz Kaczmarek and Łukasz<br />

Michalczyk.<br />

It appears that at least some researchers have paid<br />

attention to liverworts. Christenberry (1979) found<br />

Echiniscus kofordi and E. cavagnaroi on liverworts in<br />

Alabama, USA. Hinton and Meyer (2009) found<br />

Milnesium tardigradum (Figure 20) and Macrobiotus<br />

hibiscus in a liverwort sample from Georgia, USA.<br />

Michalczyk and Kaczmarek (2006) found a new species,<br />

Paramacrobiotus magdalenae (see Figure 24), on<br />

Macrobiotus anderssoni<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Macrobiotus recens<br />

Macrobiotus snaresensis<br />

Plagiochila fasciculata Diphascon scoticum<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Plagiochila obscura Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Pseudechiniscus suillus<br />

Plagiochila strombifolia Macrobiotus anderssoni<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Porella elegantula Doryphoribius zyxiglobus<br />

Echiniscus vinculus<br />

Diphascon alpinum<br />

Diphascon bullatum<br />

Diphascon prorsirostre<br />

Hypsibius convergens<br />

Isohypsibius sattleri<br />

Macrobiotus anderssoni<br />

Macrobiotus furciger<br />

Macrobiotus coronatus<br />

Macrobiotus hibiscus<br />

Minibiotus intermedius<br />

Minibiotus aculeatus<br />

Macrobiotus liviae<br />

Milnesium tardigradum<br />

Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae<br />

liverworts in Costa Rica. Newsham et al. (2006) identified<br />

the leafy liverwort Cephaloziella varians and used it to<br />

experiment on the effects of low temperature storage on<br />

tardigrades and other Antarctic invertebrates.<br />

Just what do we mean by "appropriate habitat<br />

conditions"? The bryophytes only occur in conditions that<br />

are appropriate for them, hence defining the conditions for<br />

the tardigrades. And the bryophytes create habitat<br />

conditions of moisture due to their morphology and<br />

substrate preference. Lack of species preference in many<br />

studies may result from methods that were insensitive to<br />

subtle differences or that failed to control for microhabitat<br />

differences. Usually no statistical tests were employed,<br />

sample sizes were small, and enumeration was often simple<br />

presence/absence data.<br />

Figure 24. Paramacrobiotus areolatus. Photo by Martin<br />

Mach.

Substrate Comparisons<br />

Meyer (2006) extended the comparison of substrata in<br />

Florida, USA, to include not only liverworts, mosses, and<br />

foliose lichens, but also ferns. They found 20 species of<br />

tardigrades on 47 species of plants and lichens. They found<br />

that some species were positively associated with mosses<br />

or with foliose lichens, but as in most other studies, there<br />

was no association with any particular plant or lichen<br />

species.<br />

Guil et al. (2009a) reviewed tardigrades and their<br />

habitats (altitude, habitat characteristics, local habitat<br />

structure or dominant leaf litter type, and two bioclimatic<br />

classifications), including bryophytes and leaf litter at<br />

various elevations. They were able to show some habitat<br />

preference. <strong>Species</strong> richness was most sensitive to<br />

bioclimatic classifications of macroenvironmental gradients<br />

(soil and climate), vegetation structure, and leaf litter type.<br />

A slight altitude effect was discernible. These relationships<br />

suggest that differences among bryophyte species should<br />

exist where bryophyte species occupy different<br />

environmental types or maintain different<br />

microenvironments within a habitat. But it also suggests<br />

that within the same habitat, bryophytes of various growth<br />

forms should provide different moisture regimes, hence<br />

creating species relationship differences.<br />

In a different study in the Iberian Peninsula, Guil et al.<br />

(2009b) found that leaf litter habitats showed high species<br />

richness and low abundances compared to rock habitats<br />

(mosses and lichens), which had intermediate species<br />

richness and high abundances. Tree trunk habitats (mosses<br />

and lichens) showed low numbers of both richness and<br />

abundances. One might conclude that the moisture of these<br />

habitats is the overall determining factor, and this should<br />

coincide with bryophyte species groups on the large scale.<br />

Miller et al. (1996) found six species of tardigrades in<br />

lichen and bryophyte samples on ice-free areas at Windmill<br />

Islands, East Antarctica. The tardigrade species Diphascon<br />

chilenense (see Figure 25), Hypsibius antarcticus (see<br />

Figure 26), and Pseudechiniscus suillus showed a positive<br />

association with bryophytes and a negative association with<br />

algae and lichens.<br />

Figure 25. Diphascon sp., member of one of the most<br />

common bryophyte-dwelling genera. Photo by Martin Mach.<br />

Meyer and Hinton (2007) reviewed the Nearctic<br />

tardigrades (Greenland, Canada, Alaska, continental USA,<br />

northern Mexico). They found that one-third of the species<br />

occur in both cryptogams (lichens and bryophytes) and<br />

<strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong> 53<br />

soil/leaf litter (Table 4). Few tardigrades occurred<br />

exclusively in soil/leaf litter habitats. Although many<br />

occurred among both bryophytes and lichens, 18 species<br />

occurred only in bryophytes.<br />

Figure 26. Hypsibius. Photo by Yuuji Tsukii.<br />

Table 4. Comparison of tardigrades inhabiting their primary<br />

substrates in the Nearctic realm. Only species present on that<br />

substrate in at least three sites are included. From Meyer &<br />

Hinton 2007.<br />

Substrate category number of species<br />

Cryptogams only 64<br />

Both cryptogams and soil/leaf litter 27<br />

Soil/leaf litter only 3<br />

Both bryophyte and lichen 50<br />

<strong>Bryophyte</strong> only 18<br />

Lichen only 5<br />

Beasley (1990) conducted a similar study in Colorado,<br />

USA. Out of 135 samples of liverworts, mosses, lichens,<br />

and club mosses (Lycopodiaceae), they found 20 species on<br />

55 samples. There were no tardigrades on the liverworts,<br />

but they were on 46% of mosses and 43% of lichens. The<br />

big surprise is that 75% of the clubmosses had tardigrades.<br />

In the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Bartels<br />

and Nelson (2006) found that the number of species<br />

differed little among the substrates they sampled (soil,<br />

lichen, moss, & stream habitats). Whereas it is not unusual<br />

for the soil, lichens, and mosses to have similar fauna and<br />

richness, it seems a bit unusual for the stream habitat to be<br />

as rich.<br />

Horning et al. (1978) collected from soil, fungi, algae,<br />

bryophytes, lichens, marine substrata, freshwater substrata,<br />

and litter in New Zealand and surrounding islands. From<br />

bryophyte and lichen habitats, they found that all 14 of the<br />

most abundant species occurred in at least three of the five<br />

"plant" categories (three lichen forms, liverworts, and<br />

mosses). Among these, the highest occurrence was among<br />

mosses. Although Milnesium tardigradum (Figure 20) was<br />

slightly more abundant on lichens than on mosses, the<br />

combined numbers on mosses and liverworts was still<br />

higher. Horning et al. identified the bryophytes and lichens<br />

and presented the species of tardigrades on each (Table 1,<br />

Table 3, Table 5). In 559 moss samples, 45.8% had<br />

tardigrades, mean of 1.8 species, range 1-8 (Table 1). Of<br />

55 species of tardigrades known for New Zealand, 45<br />

occurred on mosses.

54 <strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong><br />

Table 5. Comparison of numbers of individuals and percentage of individuals of 14 tardigrade species on liverworts, mosses, and<br />

lichens in collections from New Zealand and surrounding islands. From Horning et al. 1978.<br />

n liverworts % mosses % lichens %<br />

(150) (559) (239)<br />

Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae 46 8.70 56.50 23.90<br />

Pseudechiniscus suillus 43 6.98 44.19 27.91<br />

Macrobiotus harmsworthi 89 5.62 55.06 34.83<br />

Macrobiotus hibiscus 90 7.78 60.00 17.78<br />

Minibiotus intermedius 65 7.69 41.54 32.30<br />

Milnesium tardigradum 143 7.69 35.66 37.06<br />

Hypsibius dujardini 32 10.53 50.00 2.63<br />

Paramacrobiotus areolatus (Figure 27) 58 3.45 60.34 18.97<br />

Echiniscus bigranulatus 18 5.56 38.89 38.89<br />

Hypechiniscus gladiator 21 19.05 61.90 9.50<br />

Diphascon scoticum 35 11.43 65.71 11.43<br />

Macrobiotus liviae 72 8.33 56.94 18.06<br />

Macrobiotus anderssoni 63 11.11 42.86 22.22<br />

Macrobiotus furciger 89 12.36 50.56 22.47<br />

Figure 27. Paramacrobiotus areolatus, a tardigrade that<br />

inhabits both mosses and liverworts. Photo by Björn Sohlenius at<br />

the Swedish Museum of Natural History.<br />

Finding New <strong>Species</strong><br />

The common appearance of tardigrades among<br />

bryophytes causes those who seek to describe new taxa to<br />

go first to the mossy habitats. In this spirit, Kaczmarek and<br />

Michalczyk (2004a) found the new species of mossdwelling<br />

Doryphoribius quadrituberculatus in Costa Rica.<br />

From mosses in China they described the new species<br />

Bryodelphax brevidentatus (Kaczmarek et al. 2005) and B.<br />

asiaticus (Kaczmarek & Michalczyk 2004b), as did Li and<br />

coworkers for Echiniscus taibaiensis (Wang & Li 2005),<br />

Isohypsibius taibaiensis (Li & Wang 2005), Isohypsibius<br />

qinlingensis (Li et al. 2005a), Pseudechiniscus papillosus<br />

(Li et al. 2005b), Pseudechiniscus beasleyi, Echiniscus<br />

nelsonae, and E. shaanxiensis (Li et al. 2007), and<br />

Tumanov (2005) for Macrobiotus barabanovi and M.<br />

kirghizicus. Pilato and Bertolani (2005) described<br />

Diphascon dolomiticum from Italy.<br />

New species from South Africa are no surprise, as<br />

enumeration of small organisms in that country is barely<br />

out of its infancy. Kaczmarek and Michalczyk (2004c)<br />

described the new species Diphascon zaniewi in the<br />

Dragon Mountains there. Other species found there were<br />

more cosmopolitan: Hypsibius maculatus (previously<br />

known only from Cameroon and England), H. convergens<br />

(Figure 28), Paramacrobiotus cf. richtersi, and Minibiotus<br />

intermedius (Figure 29). But the South African tardigrade<br />

fauna still remains largely unknown.<br />

Figure 28. Hypsibius convergens, a moss-dweller. Photo by<br />

Björn Sohlenius, Swedish Museum of Natural History.<br />

Figure 29. Minibiotus intermedius mouth. Photo by Łukasz<br />

Kaczmarek and Łukasz Michalczyk.<br />

Likewise, in South America, Michalczyk and<br />

Kaczmarek (2005) described Calohypsibius maliki as a new<br />

species from Chile; Michalczyk and Kaczmarek (2006)<br />

described Echiniscus madonnae (Figure 30) from Peru, all<br />

from bryophytes. In Argentina they described Macrobiotus<br />

szeptyckii and Macrobiotus kazmierskii (Kaczmarek &

Michalczyk 2009). In 2008 Degma et al. described another<br />

new species (Paramacrobiotus derkai) from Chile, a<br />

country where only 29 species had previously been<br />

described.<br />

Figure 30. Echiniscus madonnae, a moss dweller from Peru.<br />

Photo by Łukasz Kaczmarek & Łukasz Michalczyk.<br />

In Portugal, lichens and mosses provided the new<br />

species Minibiotus xavieri to Fontoura and coworkers<br />

(2009). In Cyprus, Kaczmarek and Michalczyk (2004d)<br />

described Macrobiotus marlenae (Figure 31). Macrobiotus<br />

kovalevi proved to be a new species from mosses in New<br />

Zealand (Tumanov 2004). Clearly, mosses have been a<br />

favorite sampling substrate for tardigrade seekers<br />

(Kaczmarek & Michalczyk 2009) and most likely hold<br />

many more undescribed species around the world.<br />

Figure 31. Macrobiotus marlenae. Photo by Łukasz<br />

Kaczmarek and Łukasz Michalczyk.<br />

Summary<br />

Most studies indicate no correlation between<br />

bryophyte species and tardigrade species. There is<br />

limited indication that cushions may have more, but in<br />

other studies thin mats have more than cushions. Other<br />

studies indicate they are more common on weft-forming<br />

mosses than on turfs. Open mosses like Polytrichum<br />

seem to be less suitable as homes. There may be some<br />

specificity for liverworts rather than mosses, as for<br />

example Macrobiotus snaresensis in New Zealand.<br />

Unfortunately, many researchers have not identified the<br />

bryophyte taxa in tardigrade faunistic studies. A<br />

common garden study including several bryophyte<br />

species and tardigrades of the same or different species<br />

could be revealing.<br />

<strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong> 55<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

Roberto Bertolani provided an invaluable update to the<br />

tardigrade taxonomic names and offered several<br />

suggestions on the text to provide clarification or correct<br />

errors. Łukasz Kaczmarek has provided me with<br />

references, images, contact information, and a critical read<br />

of an earlier version of the text. Martin Mach and Yuuji<br />

Tsukii have given permission to use images that illustrate<br />

the species. Michael Lüth has given permission to use his<br />

many bryophyte images, and my appreciation goes to all<br />

those who have contributed their images to Wikimedia<br />

Commons for all to use. Thank you to my sister, Eileen<br />

Dumire, for providing the view of a novice on the<br />

readability of the text. Tardigrade nomenclature is based<br />

on Degma et al. 2010.<br />

Literature Cited<br />

Bartels, P. J. and Nelson, D. R. 2006. A large-scale, multihabitat<br />

inventory of the phylum Tardigrada in the Great Smoky<br />

Mountains National Park, USA: A preliminary report.<br />

Hydrobiologia 558: 111-118.<br />

Baxter, W. H. 1979. Some notes on the Tardigrada of North<br />

Down, including one addition to the Irish fauna. Irish Nat. J.<br />

19: 389-391.<br />

Beasley, C. W. 1990. Tardigrada from Gunnison Co., Colorado,<br />

with the description of a new species of Diphascon. Southw.<br />

Nat. 35: 302-304.<br />

Beasley, C. W. and Miller, W. R. 2007. Tardigrada of Xinjiang<br />

Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Proceedings of the<br />

Tenth International Symposium on Tardigrada. J. Limnol.<br />

66(Suppl. 1): 49-55.<br />

Bertolani, R. 1983. Tardigardi muscicoli delle dune costiere<br />

Italiane, con descrizione di una nuova specie. Atti Soc.<br />

Tosc. Sci. Nat. Mem. Ser. B 90: 139-148.<br />

Bertrand, M. 1975. Répartition des tardigrades "terrestres" dans<br />

le massif de l'Aigoual. Vie Milieu 25: 283-298.<br />

Christenberry, D. 1979. On the distribution of Echiniscus kofordi<br />

and E. cavagnaroi (Tardigrada). Trans. Amer. Microsc. Soc.<br />

98: 469-471.<br />

Collins, M. and Bateman, L.. 2001. The ecological distribution of<br />

tardigrades in Newfoundland. Zool. Anz. 240:291-297.<br />

Degma, P. 2006. First records of two Heterotardigrada<br />

(Tardigrada) species in Slovakia. Biologia Bratislava 61:<br />

501-502.<br />

Degma, P., Bertolani, R., and Guidetti, R. 2010. Actual checklist<br />

of Tardigrada species (Ver. 11:26-01-2010). Accessed 18<br />

June 2010 at <<br />

http://www.tardigrada.modena.unimo.it/miscellanea/Actual<br />

%20checklist%20of%20Tardigrada.pdf>.<br />

Degma, P., Simurka, M., and Gulanova, S. 2005. Community<br />

structure and ecological macrodistribution of moss-dwelling<br />

water bears (Tardigrada) in Central European oak-hornbeam<br />

forests (SW Slovakia). Ekologia (Bratislava) 24(suppl. 2):<br />

59-75.<br />

Degma, P., Michalczyk, Ł., and Kaczmarek, Ł. 2008.<br />

Macrobiotus derkai, a new species of Tardigrada<br />

(Eutardigrada, Macrobiotidae, huziori group) from the<br />

Colombian Andes (South America). Zootaxa 1731: 1-23.<br />

Fontoura, P., Pilato, G., Morais, P., and Lisi, O. 2009.<br />

Minibiotus xavieri, a new species of tardigrade from the<br />

Parque Biológico de Gaia, Portugal (Eutardigrada:<br />

Macrobiotidae). Zootaxa 2267: 55-64.

56 <strong>Chapter</strong> 5-4: <strong>Tardigrades</strong>: <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Relationships</strong><br />

Fullard, H. 1968. China in Maps. George Philip & Sons, Ltd.,<br />

London, 25 pp.<br />

Guil, N., Hortal, J., Sanchez-Moreno, S. and Machordom, A.<br />

2009a. Effects of macro and micro-environmental factors on<br />

the species richness of terrestrial tardigrade assemblages in<br />

an Iberian mountain environment. Landscape Ecol. 24: 375-<br />

390.<br />

Guil, N., Sanchez-Moreno, S., and Machordom, A. 2009b. Local<br />

biodiversity patterns in micrometazoans: Are tardigrades<br />

everywhere? System. Biodiv. 7: 259-268.<br />

Hinton, J. G. and Meyer, H. A. 2009. <strong>Tardigrades</strong> from Fayette<br />

County, Georgia. Georgia J. Sci. 67(2): 30-32.<br />

Hofmann, I. 1987. Habitat preference of the most frequent mossliving<br />

Tardigrada in the area of Giessen (Hessen). In:<br />

Bertolani, R. (ed.). Biology of <strong>Tardigrades</strong>. Selected<br />

Symposia and Monographs U.Z.I., Mucchi, Modena Italia,<br />

pp 211-216.<br />

Hofmann, I. and Eichelberg, D. 1987. Faunistisch-oekologische<br />

Untersuchungen zur Habitat-praeferenz moosbewohnender<br />

Tardigraden. [Ecological investigations of the habitat<br />

preference of moss-inhabiting tardigrades.]. Zool. Beitr.<br />

31(1): 61-76.<br />

Horning, D. S., Schuster, R. O., and Grigarick, A. A. 1978.<br />

Tardigrada of New Zealand. N. Zeal. J. Zool. 5: 185-280.<br />

Hunter, M. A. 1977, A study of Tardigrada from a farm in<br />

Montgomery County, Tennessee: MS Thesis, Austin Peay<br />

State University, 61 p.<br />

Jönsson, K. I. 2003. Population density and species composition<br />

of moss-living tardigrades in a boreo-nemoral forest.<br />

Ecography 26: 356-364.<br />

Kaczmarek, L. and Michalczyk, L. 2004a. First record of the<br />

genus Doryphoribius Pilato, 1969 from Costa Rica (Central<br />

America) and description of a new species Doryphoribius<br />

quadrituberculatus (Tardigrada: Hypsibiidae). Genus 15:<br />

447-453.<br />

Kaczmarek, L. and Michalczyk, L. 2004b. A new species<br />

Bryodelphax asiaticus (Tardigrada: Heterotardigrada:<br />

Echiniscidae) from Mongolia (Central Asia). Raffles Bull.<br />

Zool. 52: 599-602.<br />

Kaczmarek, L. and Michalczyk, L. 2004c. Notes on some<br />

tardigrades from South Africa, with the description of<br />

Diphascon (Diphascon) zaniewi sp. nov. (Eutardigrada:<br />

Hypsibiidae). Zootaxa 576: 1-6.<br />

Kaczmarek, L. and Michalczyk, L. 2004d. New records of<br />

Tardigrada from Cyprus with a description of the new<br />

species Macrobiotus marlenae (hufelandi group)<br />

(Eutardigrada: Macrobiotidae). Genus 15: 141-152.<br />

Kaczmarek, Ł. and Michalczyk, Ł. 2009. Two new species of<br />

Macrobiotidae, Macrobiotus szeptyckii (harmsworthi group)<br />

and Macrobiotus kazmierskii (hufelandi group) from<br />

Argentina. Acta Zool. Cracoviensia, Seria B - Invertebrata<br />

52: 87-99.<br />

Kaczmarek, L., Michalczyk, L., and Degma, P. 2005. A new<br />

species of Tardigrada Bryodelphax brevidentatus sp. nov.<br />

(Heterotardigrada: Echiniscidae) from China (Asia).<br />

Zootaxa 1080: 33-38.<br />

Kathman, R. D. and Cross, S. F. 1991. Ecological distribution of<br />

moss-dwelling tardigrades on Vancouver Island, British<br />

Columbia, Canada. Can. J. Zool. 69: 122-129.<br />

Li, X.-C. and Wang, L.-Z. 2005. Isohypsibius taibaiensis sp.<br />

nov. (Tardigrada, Hypsibiidae) from China. Zootaxa 1036:<br />

55-60.<br />

Li, X.-C., Wang, L.-Z. and Yu, D. 2005a. Isohypsibius<br />

qinlingensis sp. nov. (Tardigrada, Hypsibiidae) from China.<br />

Zootaxa 980: 1-4.<br />

Li, X.-C., Wang, L.-Z., and Yu, D. 2007. The Tardigrada fauna<br />

of China with descriptions of three new species of<br />

Echiniscidae. Zool. Stud. 46(2): 135-147.<br />

Li, X.-C., Wang, L.-Z., Liu, Y., and Su, L.-N. 2005b. A new<br />

species and five new records of the family Echiniscidae<br />

(Tardigrada) from China. Zootaxa 1093: 25-33.<br />

Meyer, H. A . 2006. Small-scale spatial distribution variability in<br />

terrestrial tardigrade populations. Hydrobiologia 558: 133-<br />

139.<br />

Meyer, H. A. and Hinton, J. G. 2007. Limno-terrestrial<br />

Tardigrada of the Nearctic realm. J. Limnol. 66(Suppl. 1):<br />

97-103.<br />

Michalczyk, L. and Kaczmarek, L. 2005. The first record of the<br />

genus Calohypsibius Thulin, 1928 (Eutardigrada:<br />

Calohypsibiidae) from Chile (South America) with a<br />

description of the new species Calohypsibius maliki. New<br />

Zeal. J. Zool. 32: 287-292.<br />

Michalczyk, Ł. and Kaczmarek, Ł. 2006. Revision of the<br />

Echiniscus bigranulatus group with a description of a new<br />

species Echiniscus madonnae (Tardigrada:<br />

Heterotardigrada: Echiniscidae) from South America.<br />

Zootaxa 1154: 1-26.<br />

Miller, W. R., Miller, J. D., and Heatwole, H. 1996.<br />

<strong>Tardigrades</strong> of the Australian Antarctic Territories: The<br />

Windmill Islands, East Antarctica. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 116:<br />

175-184.<br />

Nelson, D. R. 1973. Ecological distribution of tardigrades on<br />

Roan Mountain, Tennessee – North Carolina. Ph. D.<br />

dissertation, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.<br />

Nelson, D. R. 1975. Ecological distribution of Tardigrada on<br />

Roan Mountain, Tennessee - North Carolina. In: Higgins,<br />

R. P. (ed.). Proceedings of the First International<br />

Symposium on <strong>Tardigrades</strong>. Mem. Ist. Ital. Idrobiol., Suppl.<br />

32: 225-276.<br />

Newsham, K. K., Maslen, N. R., and McInnes, S. J. 2006.<br />

Survival of Antarctic soil metazoans at -80ºC for six years.<br />

CryoLetters 27(5): 269-280.<br />

Pilato, G. and Bertolani, R. 2005. Diphascon (Diphascon)<br />

dolomiticum, a new species of Hypsibiidae (Eutardigrada)<br />

from Italy. Zootaxa 914: 1-5.<br />

Ramazzotti, G. and Maucci, W. 1983. The phylum Tardigrada –<br />

3rd edition: English translation by C. W. Beasley. Mem. Ist.<br />

Ital. Idrobiol. Dott. Marco de Marchi 41: 1B680.<br />

Romano, F. A. III., Barreras-Borrero, B., and Nelson, D. R. 2001.<br />

Ecological distribution and community analysis of<br />

Tardigrada from Choccolocco Creek, Alabama. Zool. Anz.<br />

240: 535-541.<br />

Sayre, R. M. and Brunson, L. K. 1971. Microfauna of moss<br />

habitats. Amer. Biol. Teacher Feb. 1971: 100-102, 105.<br />

Swedish Museum of Natural History. 2009. Microfauna on<br />

Antarctic nunataks. Accessed on 14 February 2010 at<br />

.<br />

Tumanov, D. V. 2004. Macrobiotus kovalevi, a new species of<br />

Tardigrada from New Zealand (Eutardigrada,<br />

Macrobiotidae). Zootaxa 406: 1-8.<br />

Tumanov, D. V. 2005. Two new species of Macrobiotus<br />

(Eutardigrada, Macrobiotidae) from Tien Shan (Kirghizia),<br />

with notes on Macrobiotus tenuis group. Zootaxa 1043: 33-<br />

46.<br />

Wang, L.-Z. and Li, X.-C. 2005. Echiniscus taibaiensis sp. nov.<br />

and a new record of Echiniscus bisetosus Heinis (Tardigrada,<br />

Echiniscidae) from China. Zootaxa 1093: 39-45.