TSITONGAMBARIKA FOREST, MADAGASCAR - BirdLife International

TSITONGAMBARIKA FOREST, MADAGASCAR - BirdLife International

TSITONGAMBARIKA FOREST, MADAGASCAR - BirdLife International

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>TSITONGAMBARIKA</strong> <strong>FOREST</strong>,<br />

<strong>MADAGASCAR</strong><br />

Biological and socio-economic surveys, with<br />

conservation recommendations<br />

Edited by<br />

John Pilgrim, Narisoa Ramanitra, Jonathan Ekstrom, Andrew W. Tordoff and Roger J. Safford<br />

Fieldwork<br />

coordinated by<br />

Maps by<br />

Andriamandranto Ravoahangy<br />

Translation by<br />

Kobele Keita and Andry Rakotomalala<br />

Fieldwork funded<br />

and additional<br />

fieldwork by<br />

■<br />

Additional<br />

fieldwork by<br />

Additional<br />

fieldwork by<br />

French translation<br />

checked by

Recommended citation: <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong> (2011) Tsitongambarika Forest, Madagascar. Biological and<br />

socio-economic surveys, with conservation recommendations. Cambridge, UK: <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong>.<br />

© 2011 <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

Wellbrook Court, Girton Road, Cambridge CB3 0NA, United Kingdom<br />

Tel: +44 1223 277318 Fax: +44 1223 277200 email: birdlife@birdlife.org<br />

Internet: www.birdlife.org<br />

<strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong> is a UK-registered charity 1042125<br />

ISBN 978-0-946888-78-8<br />

British Library-in-Publication Data<br />

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library<br />

First published 2011 by <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

Designed and produced by NatureBureau Limited, 36 Kingfisher Court, Hambridge Road, Newbury, Berkshire,<br />

RG14 5SJ, United Kingdom<br />

Printed by Information Press, Oxford, United Kingdom<br />

Available from the Natural History Book Service Ltd, 2–3 Wills Road, Totnes, Devon TQ9 5XN, UK.<br />

Tel: +44 1803 865913 Fax: +44 1803 865280 Email: nhbs@nhbs.co.uk<br />

Internet: www.nhbs.com/services/birdlife.html<br />

ii

■ CONTENTS<br />

iv Participants and authors<br />

vi Acknowledgements<br />

1 Introduction<br />

2 Summary of findings<br />

4 Ny alan’ i Tsitongambarika, Madagasikara<br />

Famintinana (Summary in Malagasy)<br />

6 Recommendations<br />

8 Ny alan’ i Tsitongambarika, Madagasikara<br />

Tolo-Kevitra (Recommendations in Malagasy)<br />

10 Chapter 1: Overview of the biological<br />

importance of Tsitongambarika Forest<br />

10 Background<br />

10 The surveys<br />

10 Vegetation and flora<br />

12 Mammals<br />

12 Reptiles and amphibians<br />

12 Birds<br />

14 Ants<br />

14 Other values of the Tsitongambarika Forests<br />

15 Socio-economic situation<br />

15 Management situation<br />

16 Relevance of survey results for conservation<br />

planning<br />

16 Direct payments project<br />

17 Chapter 2: The flora of Tsitongambarika<br />

Forest<br />

17 Introduction<br />

17 Objectives<br />

17 Study site<br />

17 Methodology<br />

17 Results<br />

22 Conservation<br />

22 Recommendations<br />

22 Conclusions<br />

23 Chapter 3: The bats of Tsitongambarika<br />

Forest<br />

23 Introduction<br />

23 Obectives<br />

25 Study sites<br />

25 Methods<br />

25 Results<br />

26 Discussion<br />

27 Recommendations<br />

28 Chapter 4: The lemurs of Tsitongambarika<br />

Forest<br />

28 Objectives<br />

28 Study sites<br />

28 Methods<br />

30 Results<br />

32 Discussion<br />

33 Conclusions<br />

33 Recommendations<br />

34 Chapter 5: The herpetofauna of<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest<br />

34 Introduction<br />

34 Study sites<br />

36 Methods<br />

36 Results<br />

40 Discussion<br />

41 Conclusions<br />

41 Recommendations<br />

42 Chapter 6: The birds of Tsitongambarika Forest<br />

42 Objectives<br />

42 Methods<br />

45 Study sites<br />

47 Results<br />

53 Discussion<br />

55 Recommendations<br />

57 Chapter 7: The ants of the Ivohibe region of<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest<br />

57 Introduction<br />

57 Study sites<br />

57 Survey methods<br />

57 Results and discussion<br />

60 Chapter 8: Socio-economic survey of the<br />

Tsitongambarika area<br />

60 Objectives<br />

60 Methodology<br />

60 Social organisation<br />

62 Demographic situation<br />

67 Discussion<br />

68 Importance of biodiversity to communities<br />

70 Threats to biodiversity<br />

71 Conservation of biodiversity<br />

72 Conclusions<br />

72 Recommendations<br />

74 References<br />

77 Appendix: Community involvement in<br />

management of Tsitongambarika Forest:<br />

2010 update<br />

iii

Lalao Andriamahefarivo (Botanist)<br />

Missouri Botanical Garden, BP 3391,<br />

Antananarivo, Madagascar<br />

Maminiaina Andriamahenitsoa (Socio-economist)<br />

Asity Madagascar, BP 1074, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

Patrice Antilahimena (Botanist)<br />

Missouri Botanical Garden, BP 3391,<br />

Antananarivo, Madagascar<br />

Mara Berge (Guide and President of Antsotso<br />

Communauté de Base)<br />

Antsotso, Fort Dauphin/Tolagnaro, Madagascar<br />

Chris Birkinshaw (Botanist)<br />

Missouri Botanical Garden, BP 3391,<br />

Antananarivo, Madagascar<br />

Ramisy Edmond (Parataxonomist)<br />

Rio Tinto QMM, BP 225, Fort Dauphin/<br />

Tolagnaro, Madagascar<br />

Jonathan Ekstrom (Editor)<br />

<strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong>, Wellbrook Court, Girton<br />

Road, Cambridge, UK<br />

Current address: The Biodiversity Consultancy,<br />

4 Woodend, Trumpington, Cambridge, UK<br />

Brian Fisher (Entomologist)<br />

California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music<br />

Concourse Drive, San Francisco, USA<br />

Soanary Claude Hery (Assistant)<br />

Rio Tinto QMM, BP 225, Fort Dauphin/Tolagnaro,<br />

Madagascar<br />

Porter P. Lowry II (Botanist)<br />

Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St.<br />

Louis, MO, 63166-0299, USA<br />

and Département Systématique et Evolution (UMR<br />

7205), Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP<br />

39, 57 Rue Cuvier, 75213 Paris CEDEX 05, France<br />

Eric Lowry (Student, MBG trainee)<br />

Missouri Botanical Garden, BP 3391,<br />

Antananarivo, Madagascar<br />

Tsibara Mbohoahy (Chiropterologist)<br />

Madagasikara Voakajy, BP 5181, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

and Biodiversité et environnement, Département de<br />

la Biologie, Faculté des Sciences de l’Université de<br />

Toliara, Toliara, Madagascar<br />

Current address: Biodiversité et Environnement,<br />

iv<br />

■ PARTICIPANTS AND AUTHORS<br />

Département de la Biologie, Faculté des Sciences de<br />

l’Université de Toliara, Toliara, Madagascar<br />

John Pilgrim (Editor)<br />

The Biodiversity Consultancy, 4 Woodend,<br />

Trumpington, Cambridge, UK<br />

Rivo Rabarisoa (Ornithologist)<br />

Asity Madagascar, BP 1074, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

Marc Rabenandrasana (Ornithologist)<br />

Asity Madagascar, BP 1074, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

Current addresses: Development and Biodiversity<br />

Conservation Action for Madagascar, Lot II A<br />

93L, Anjanahary, Antananarivo, Madagascar<br />

and ECOMAR (Marine Ecology Laboratory),<br />

Sciences and Technology Faculty, University of<br />

La Réunion, 15 Avenue René Cassin, BP 7151 –<br />

97715 Saint-Denis, La Réunion.<br />

Johny Rabenantoandro (Botanist)<br />

Rio Tinto QMM, BP 225, Fort Dauphin/<br />

Tolagnaro, Madagascar<br />

Marie Beatrice Yvonne Rahasinandrasana<br />

(Socio-economist)<br />

Asity Madagascar, BP 1074, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

Rivo Rajoharison (Forestry Technician)<br />

Rio Tinto QMM, BP 225, Fort Dauphin/<br />

Tolagnaro, Madagascar<br />

Mamy Julia Christobelle Ralavanirina<br />

(Primatologist)<br />

Asity Madagascar, BP 1074, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

and Département Biologie Animale, Université<br />

d’Antananarivo<br />

Current address: 2 Allée du Collier, 40230 St<br />

Vincent de Tyrosse, France<br />

Jean Baptiste Ramanamanjato (Herpetologist)<br />

Rio Tinto QMM, BP 225, Fort Dauphin/<br />

Tolagnaro, Madagascar<br />

Michael Ramanesimanana (Ornithologist)<br />

Asity Madagascar, BP 1074, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

and Département Biologie Animale, Université<br />

d’Antananarivo<br />

Current address: Maromizaha Project Coordinator,<br />

GERP Madagascar (Groupe d’Etude et de Recherche<br />

sur les Primates), BP 779, Antananarivo, Madagascar

Narisoa Ramanitra (Ornithologist, Programme<br />

Coordinator and Editor)<br />

Asity Madagascar, BP 1074, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

and Département Biologie Animale, Université<br />

d’Antananarivo<br />

Faly Randriatafika (Botanist)<br />

Rio Tinto QMM, BP 225, Fort Dauphin/<br />

Tolagnaro, Madagascar<br />

Lovahasina Rasolondraibe (Ornithologist)<br />

Asity Madagascar, BP 1074, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

and Département Biologie Animale, Université<br />

d’Antananarivo<br />

Current address: Biologist, GERP Madagascar<br />

(Groupe d’Etude et de Recherche sur les Primates),<br />

BP 779, Antananarivo, Madagascar<br />

Bruno Raveloson (Ornithologist)<br />

Asity Madagascar, BP 1074, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

Collared Nightjar Caprimulgus enarratus (ANDRIAMANDRANTO RAVOAHANGY)<br />

Andriamandranto Ravoahangy (Tsitongambarika<br />

Programme Coordinator)<br />

Asity Madagascar, BP 1074, Antananarivo,<br />

Madagascar<br />

Julien Razafimandimby (Assistant)<br />

Rio Tinto QMM, BP 225, Fort Dauphin/<br />

Tolagnaro, Madagascar<br />

Richard Razakamalala (Botanist)<br />

Missouri Botanical Garden, BP 3391,<br />

Antananarivo, Madagascar<br />

Roger Safford (Editor)<br />

<strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong>, Wellbrook Court,<br />

Girton Road, Cambridge, UK<br />

Andrew W. (“Jack”) Tordoff (Editor)<br />

<strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong>, Wellbrook Court,<br />

Girton Road, Cambridge, UK<br />

Current address: Critical Ecosystem Partnership<br />

Fund, Conservation <strong>International</strong>, 2011 Crystal<br />

Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, Virginia, USA<br />

v

The biological survey and socio-economic study of<br />

Tsitongambarika forest and its surrounding areas<br />

were carried out with contributions from many<br />

organizations and individuals specialised in different<br />

disciplines and taxa.<br />

We first thank Rio Tinto and <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

who were jointly responsible for initiating this<br />

programme of surveys. In particular, we thank the<br />

partners of Rio Tinto and <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong>,<br />

including Rio Tinto QMM (QIT Madagascar<br />

Minerals, QMM) and the <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

Madagascar Programme, and their partners Asity<br />

Madagascar (formerly Asity), the Missouri Botanical<br />

Garden (MBG), and Madagasikara Voakajy.<br />

This study would not have been possible without<br />

the financial and logistical support of Rio Tinto<br />

and Rio Tinto QMM, where we especially thank Stuart<br />

Anstee and Manon Vincelette respectively.<br />

We also thank the Whitley Awards Foundation<br />

for <strong>International</strong> Nature Conservation: Rufford Small<br />

Grants for funding research in Tsitongambarika I and<br />

II in 2002. The design and organization of this program<br />

were facilitated by <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong>, at the time<br />

of the work operating through its Madagascar<br />

Programme; the <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong> Madagascar<br />

Programme closed in 2008, when Asity Madagascar<br />

became the <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong> Affiliate NGO in<br />

Madagascar and took on the management of <strong>BirdLife</strong><br />

programmes in Madagascar. Logistics and<br />

herpetological studies were performed by Rio Tinto<br />

QMM. The coordination of the work, and<br />

ornithological, primatological and socio-economic<br />

surveys were carried out by Asity Madagascar. The<br />

flora survey was carried out by an MBG/Rio Tinto<br />

QMM team. Bat surveys were carried out by<br />

Madagasikara Voakajy.<br />

All members of the team strongly supported the<br />

field efforts and subsequent writing-up: Jean Baptiste<br />

Ramanamanjato, Ramisy Edmond, Johny<br />

vi<br />

■ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

Rabenantoandro, Faly Randriatafika, Julien<br />

Razafimandimby, Rivo Rajoharison and Soanary<br />

Claude Hery from Rio Tinto QMM; Tsibara<br />

Mbohoahy from Madagasikara Voakajy; Mamy Julia<br />

Christobelle Ralavanirina, Marc Rabenandrasana,<br />

Michael Ramanesimanana, Lovahasina<br />

Rasolondraibe, Maminiaina Andriamahenintsoa,<br />

Marie Beatrice Yvonne Rahasinandrasana and<br />

Andriamandranto Ravoahangy from Asity<br />

Madagascar; Richard Razakamalala, Pete Lowry,<br />

Chris Birkinshaw, Patrice Antilahimena and Eric<br />

Lowry from MBG; Mara Berge from CoBa Antsotso;<br />

Brian Fisher from the California Academy of Sciences;<br />

Jonathan Stacey and Luciana Vega from <strong>BirdLife</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong>; and Helen Temple at The Biodiversity<br />

Consultancy. Our sincere thanks go also to the staff<br />

members of Fikambanana Mitanantana (FIMPIA,<br />

the community association at Sainte Luce), and the<br />

heads of other CoBas and heads of Districts for their<br />

efficient help during the field work. Jennifer Talbot<br />

assisted in completion of this volume in numerous<br />

ways. Maps were prepared by Andriamandranto<br />

Ravoahangy. Translation between English and<br />

French was carried out by Kobele Keita of The<br />

Biodiversity Consultancy, and Andry Rakotomalala,<br />

and the French finally checked by Marion Grassi of<br />

LPO (<strong>BirdLife</strong> in France). The Summary and<br />

Recommendations were translated into Malagasy by<br />

Voninavoko Raminoarisoa (Asity Madagascar).<br />

The work was kindly authorised by the Ministry of<br />

Environment, through the Directorate General of<br />

Environment, Water and Forest as well as its regional<br />

office (Circonscription Régionale de l’Environnement,<br />

des Eaux et Forêts) for Anosy Region in Fort Dauphin/<br />

Tolagnaro. The implementation of this work and the<br />

herpetological field data collection are the result of<br />

collaboration between Rio Tinto QMM, FIMPIA and<br />

the Committee of Protected Areas Management in the<br />

Sainte Luce area.

■ INTRODUCTION<br />

The biological and socio-economic studies in this<br />

volume were initiated as part of the Rio Tinto-<strong>BirdLife</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong> partnership. This partnership was<br />

established in 2001 in order for <strong>BirdLife</strong> to assist Rio<br />

Tinto in the development and implementation of its<br />

biodiversity strategy and goal of a Net Positive Impact<br />

(NPI) on biodiversity at mining operations, including<br />

the Rio Tinto QMM (QIT Madagascar Minerals,<br />

QMM) ilmenite project in Anosy region of south east<br />

Madagascar.<br />

The Rio Tinto QMM project was chosen as a pilot<br />

operation for NPI because of Madagascar’s highly<br />

endemic and threatened biodiversity, and the risks and<br />

opportunities that biodiversity presents to the site.<br />

Achievement of NPI is based on a mitigation hierarchy,<br />

which begins with the avoidance, mitigation and<br />

restoration of the impacts on biodiversity of a mining<br />

operation. When those have been optimised, NPI looks<br />

to the use of offsets as “quantifiable conservation<br />

actions taken to compensate for residual, unavoidable<br />

harm to biodiversity”.<br />

A biodiversity offsets strategy needs to account for<br />

biodiversity gains and losses in a transparent manner,<br />

consider intrinsic values (scientific, conservation) and<br />

service values (economic and cultural), involve relevant<br />

stakeholders at multiple levels and be based on<br />

adequate information (including both scientific and<br />

traditional knowledge). Offsets should be designed to<br />

achieve the best outcomes for conservation and<br />

traditional use and thus must consider similar habitat<br />

types to those impacted, consider opportunities for<br />

better conservation outcomes in other habitats, and<br />

may include actions to manage habitat that build<br />

capacity in institutions, people and knowledge, and<br />

that secure ecosystem services.<br />

In order to design a successful NPI strategy for<br />

the Rio Tinto QMM ilmenite project, it is thus<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest, Madagascar<br />

necessary to obtain relevant biological and socioeconomic<br />

information from potential offset sites<br />

within the Anosy region of Madagascar.<br />

Tsitongambarika humid forest was identified as a key<br />

conservation site with high biodiversity value and<br />

therefore an important potential offset site in Rio<br />

Tinto QMM’s NPI strategy.<br />

The Tsitongambarika Protected Area was created<br />

in 2008 by the Malagasy Ministry of Water and<br />

Forests with technical and financial support from<br />

Asity Madagascar (the country Affiliate of <strong>BirdLife</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong>), Rio Tinto, Rio Tinto QMM, USAID,<br />

and Conservation <strong>International</strong>. It covers an area of<br />

over 60,000 hectares of humid lowland and midaltitude<br />

forest, located just north of the town of<br />

Tolagnaro (Fort Dauphin). In addition to being an<br />

important conservation area, protecting many<br />

endemic and threatened species, it also serves as the<br />

principal watershed for the region—providing water<br />

for irrigation as well as for Tolagnaro town. The<br />

forest also provides numerous other ecosystem goods<br />

and services that ensure the economic and cultural<br />

well-being of the surrounding population. The<br />

Tsitongambarika Protected Area is currently comanaged<br />

by Asity Madagascar and more than 60<br />

community forest management groups located<br />

around the forest.<br />

The research in this volume has been carried out to<br />

provide the biological data which Rio Tinto/Rio Tinto<br />

QMM and their conservation partners used to develop<br />

Rio Tinto QMM’s NPI strategy. The decision to<br />

publish these data and make them available to a wider<br />

public and scientific community serves not only to<br />

increase our collective knowledge of the biodiversity<br />

and socio-economic situation of Tsitongambarika,<br />

but will, we hope, stimulate and encourage future<br />

biological and socio-economic research in the area.<br />

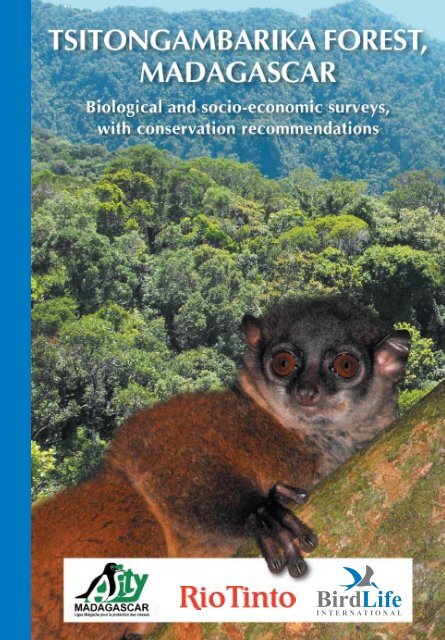

Plate 1. View of<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest<br />

(ANDRIAMANDRANTO<br />

RAVOAHANGY)<br />

1

Lowland humid evergreen forest is one of the most<br />

threatened vegetation types in Madagascar.<br />

Nonetheless, significant areas can still be found in<br />

south-eastern Madagascar, most notably the<br />

Andohahela and Tsitongambarika (Vohimena)<br />

forests in Anosy Region. Until recently, however,<br />

these forests had been the focus of little biodiversity<br />

study, and recognition of their biological importance<br />

was limited. The surveys presented in this report<br />

highlight the biological importance of the<br />

Tsitongambarika forests. In particular, they indicate<br />

that these forests are floristically and faunistically<br />

distinct from lowland humid evergreen forests<br />

elsewhere in Madagascar. Among the key findings of<br />

the surveys were the discoveries of several species of<br />

amphibian, reptile and plant new to science, and<br />

confirmation of the presence of a number of globally<br />

threatened and restricted-range species.<br />

The major conclusions from the surveys can be<br />

found below. In the following section, a number of<br />

recommendations are drawn from these conclusions<br />

for those considering conservation intervention within<br />

the Tsitongambarika massif, including altitudes, sites<br />

and species that deserve particular attention.<br />

VEGETATION AND FLORA<br />

While eastern humid forest is the most abundant<br />

natural forest formation in Madagascar, about 80%<br />

of it is mid-altitude forest between 800 and 1,500 m<br />

altitude, and relatively little remains at low elevations.<br />

However, the Tsitongambarika forests are mainly<br />

distributed below 800 m altitude, and, almost<br />

uniquely for humid forests in south-eastern<br />

Madagascar, include significant areas below 400 m.<br />

Surveys of flora focused on Bemangidy-Ivohibe<br />

Forest in Tsitongambarika III, which is notable for<br />

the presence of relatively undisturbed humid forest<br />

below 400 m altitude. In total, nearly 600 species were<br />

collected during the surveys, representing 366 genera<br />

in 121 families. Although identification of all<br />

specimens has yet to be completed, almost 70 plant<br />

species new to science may have been found in<br />

Tsitongambarika to date. The survey team estimated<br />

the flora of this area to exceed 1,000 species.<br />

MAMMALS<br />

Mammal surveys focused on lemurs and bats. Seven<br />

species of lemur were identified within<br />

2<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest, Madagascar<br />

■ SUMMARY OF FINDINGS<br />

Tsitongambarika, of which two (Collared Brown<br />

Lemur Eulemur collaris and Grey Gentle Lemur<br />

Hapalemur griseus 1 ) are globally threatened, one<br />

(Aye-aye Daubentonia madagascariensis) is Near<br />

Threatened and two more are so poorly known<br />

that they are classified as Data Deficient. Although<br />

all three sites surveyed held all seven lemur<br />

species, Ivorona appeared to hold the highest<br />

densities. All of the lemur species recorded at<br />

Tsitongambarika can also be found at the nearby<br />

Andohahela National Park, where eight species have<br />

been recorded.<br />

Seven bat species were found during surveys,<br />

including two globally threatened (Vulnerable) species<br />

and one Data Deficient species. Particularly<br />

significant populations of the threatened Madagascar<br />

Flying-fox Pteropus rufus were found, numbering<br />

about 2,000 individuals among four roosts, notably<br />

at Ivolo. Given the relatively short survey period, it<br />

is likely that further surveys at Tsitongambarika<br />

would reveal additional bat species.<br />

REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS<br />

The mountains of Anosy Region are one of the two<br />

areas in Madagascar with the highest number of<br />

globally threatened amphibian species, and the Anosy<br />

Region is also one of the richest in Madagascar for<br />

reptile species, with a number of species not known<br />

from elsewhere in the country. Comparison between<br />

amphibian and reptile species known from<br />

Tsitongambarika and those known from nearby<br />

littoral forests and the humid forests of Andohahela<br />

National Park reveals significant differences.<br />

Surveys of the Tsitongambarika forests to date,<br />

summarised in this report, have recorded 70 reptile<br />

species and 57 amphibian species. These include 12<br />

species believed restricted to the Anosy Region, six<br />

globally threatened species, four Near Threatened<br />

species, and six Data Deficient species. Although<br />

collections made during the 2006 survey have yet to<br />

be fully identified, they include four frogs (Boophis<br />

sp. and Mantidactylus spp.), a day gecko (Phelsuma<br />

sp.) and a snake (Liophidium sp.) that are thought<br />

probably to represent new species to science. Highest<br />

amphibian and reptile species richness has been<br />

recorded at Ivorona and Manantantely, but globally<br />

threatened and potentially new species are distributed<br />

patchily: all sites except Lakandava and Ivohibe held<br />

species of conservation concern not found at other<br />

sites.<br />

1 Under alternative taxonomic arrangements, the Hapalemur found at Tsitongambarika, here called H. griseus, is treated as the<br />

more geographically restricted Southern Bamboo Lemur H. meridionalis. Under either arrangement, the species is threatened;<br />

see end of Chapter 4.

BIRDS<br />

The avifauna of Tsitongambarika includes a number<br />

of lowland forest specialists—such as Scaly Groundroller<br />

Brachypteracias squamiger, Nuthatch Vanga<br />

Hypositta corallirostris and Red-tailed Newtonia<br />

Newtonia fanovanae — and other species<br />

characteristic of undisturbed humid forest, such as<br />

Brown Mesite Mesitornis unicolor, Short-legged<br />

Ground-roller Brachypteracias leptosomus, Pollen’s<br />

Vanga Xenopirostris polleni and Wedge-tailed Jery<br />

Neomixis flavoviridis. Because of its importance for<br />

globally threatened and restricted-range species,<br />

Tsitongambarika was recognised as an Important<br />

Bird Area by <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong> (ZICOMA 1999).<br />

Surveys of the Tsitongambarika forests to date,<br />

summarised in this report, have recorded 97 bird<br />

species, 57 (59%) of which are endemic to<br />

Madagascar. These include eight globally threatened<br />

and six Near Threatened species, for which the most<br />

important sites surveyed were Ivohibe and Ivorona.<br />

The avifauna of Tsitongambarika does not appear<br />

to differ greatly from that of the nearby Andohahela<br />

National Park. Further surveys at higher altitudes of<br />

Tsitongambarika, which have not been surveyed to<br />

date, are likely to emphasise similarities to<br />

Andohahela.<br />

ANTS<br />

In addition to the <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong>-coordinated<br />

surveys, an ant survey of Ivohibe Forest in<br />

Tsitongambarika III was conducted by scientists from<br />

California Academy of Sciences and the Madagascar<br />

Biodiversity Centre. A total of 105 species were<br />

recorded, with two species known only from this<br />

forest.<br />

OTHER VALUES<br />

In addition to their intrinsic biodiversity values, the<br />

Tsitongambarika forests are an important source of<br />

ecosystem goods and services. Socio-economic<br />

surveys presented in this report show that the forests<br />

are an important source of forest products for local<br />

people, including firewood, charcoal, construction<br />

materials, bushmeat and medicinal plants. Since the<br />

local economy is largely subsistence-based and there<br />

is a high incidence of poverty, local communities have<br />

a high level of dependence on forest products to meet<br />

their daily needs. Loss and degradation of forests thus<br />

has major implications for the livelihoods of local<br />

people.<br />

The Tsitongambarika forests also play an<br />

important role in carbon storage, prevention of soil<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest, Madagascar<br />

erosion, and protect the catchments of two of the<br />

Anosy region’s major rivers: the Manampanihy and<br />

Efaho. These rivers and their tributaries are the main<br />

source of water for agricultural irrigation and<br />

domestic use for rural communities in the east of the<br />

region. Further, the forests of Tsitongambarika I<br />

protect the water sources of the Lakandava pumping<br />

station and Lanirano Lake, which provide,<br />

respectively, 75% and 25% of the water for Fort<br />

Dauphin town.<br />

The Tsitongambarika forests also hold significant<br />

cultural importance for the local population. There<br />

is much evidence of historical settlement, burial sites,<br />

terraced rice cultivation and cattle pasturing within<br />

the village territories that have been designated as<br />

protected forest. In addition, the rivers, pools, and<br />

cliffs in the forest, along with actual and mythical<br />

forest creatures, are important to the traditions,<br />

beliefs and cultural identity of local people.<br />

<strong>FOREST</strong> IMPACTS AND<br />

CONSERVATION<br />

Forest clearance for shifting cultivation has the most<br />

significant impacts on the Tsitongambarika forests.<br />

Further forest clearance and degradation comes from<br />

poorly controlled fires, often set to clear cattle pasture,<br />

and timber harvesting. Although not at high levels,<br />

hunting and collecting of non-timber forest products<br />

are both starting to locally deplete some natural<br />

resources.<br />

At present, the major conservation potential has<br />

been seen to lie with the transfer of forest management<br />

to local associations. Unfortunately, since local<br />

cultural norms do not favour working in local<br />

associations and since these associations are seen as<br />

imposed by NGOs and the government, many of<br />

those that have been established remain weak. If there<br />

is agreement with the theory of these local<br />

associations, then significant support to these<br />

associations in terms of training, mentoring and<br />

oversight will be critical. However, these local<br />

associations may not be the ideal mechanism for<br />

managing the forest. There may be a need to look for<br />

a new model for working with local populations to<br />

manage the forest that recognises local rights, unequal<br />

power relations and fundamentally different value<br />

and belief systems among local, regional, national and<br />

international stakeholders. Whatever the case,<br />

multiple actors will need to commit to additional<br />

efforts in both research and management in order to<br />

ensure the long-term integrity of the Tsitongambarika<br />

forests for their unique biodiversity, for local<br />

livelihoods, well-being and culture, and for continued<br />

provision of ecosystem services for south-eastern<br />

Madagascar.<br />

3

Ireo ala mando tsy mihintsan-dravina eny amin’ny<br />

haabo iva no anisan’ireo karazan-javamaniry<br />

tandindomin-doza indrindra. Na izany aza dia mbola<br />

ahitana faritra manan-danja amin’io haabo io any<br />

amin’ny faritra atsimo antsinanan’i Madagasikara :<br />

ny alan’Andohahela sy Tsitongambarika (Vohimena<br />

raha ny marimarina kokoa). Hatramin’izao anefa dia<br />

tsy mba anisan’ireo nanaovana fikarohana, na zara<br />

raha nisy, mikasika ny zava-boahary ao aminy ireo<br />

karazan’ala ireo, hany ka tsy dia fantatra loatra ny<br />

zava-dehibe ananany. Ny voka-pikarohana izay<br />

aseho ato anatin’ity tatitra ity dia mampiseho ny lanja<br />

ara-biolojika ananan’ny alan’i Tsitongambarika.<br />

Maneho indrindra izy ity fa miavaka ireo ala ireo raha<br />

mitaha amin’ny ala mando tsy mihintsan-dravina<br />

amin’ny haabo iva hafa eto Madagasikara. Anisan’ny<br />

vokatry ny fikarohana misongadina dia ny<br />

fahitana karazana sahona sy reptilia ary zava-maniry<br />

vaovao ho an’ny siansa ; ao koa ny fahitana ireo<br />

karazan-java-manan’aina izay mila ho lany<br />

tamingana na koa tsy fahita raha tsy ao anatin’ny<br />

faritra voafetra.<br />

Ireo fehin-kevitra nisongadina tamin’io<br />

fikarohana io dia hita etsy ambany. Manarak’izany<br />

dia hisy tolo-kevitra maromaro nosintonina<br />

tamin’ireo voka-pikarohana, ho an’ireo mikasa<br />

hanao asa fiarovana ao amin’ny alan’i<br />

Tsitongambarika. Anisan’izany ireo tolo-kevitra<br />

mahakasika ireo haabo sy ny toerana ary ny karazana<br />

zava-manan’aina izay mendrika fiheverana<br />

manokana.<br />

ZAVA-MANIRY<br />

Ny ala mando atsinanana no tangoron’ala natoraly<br />

betsaka indrindra eto Madagasikara. Manodidina ny<br />

80% ny velaran’ny ala amin’ny haabo antonony eo<br />

anelanelan’ny 800 sy 1500 m ary vitsy ihany no hita<br />

amin’ny haabo iva. Nefa kosa ny ny alan’i<br />

Tsitongambarika dia manana velarana lehibe hita<br />

amin’ny haabo ambanin’ny 400 m, izay mampiavaka<br />

azy amin’ny ala atsimo atsinanana rehetra eto<br />

amin’ny nosy.<br />

Ny fanisana ireo karazana zava-maniry dia natao<br />

tao amin’ny alan’i Bemangidy-Ivohibe,<br />

Tsitongambarika faha-III, izay miavaka noho ny<br />

fisian’ny ala mbola tsara amin’io haabo latsaky ny<br />

400 m io. Eo amin’ny 600 karazana eo no zava-maniry<br />

voaiisa izay ahitana taranaka 366 sy fianakaviana<br />

121. Na dia mbola tokony ho vitaina aza ny<br />

famaritana ireo karazana ireo, dia mety eo amin’ny<br />

70 eo ny karazana zava-maniry vaovao hita ao<br />

Tsitongambarika ankehitriny. Ireo mpanao<br />

fikarohana dia manombana ho 1000 ny karazana<br />

zava-maniry ao aminy.<br />

4<br />

■ FAMINTINANA<br />

Ny Tsitongambarika alan’ i Tsitongambarika, Forest, Madagascar<br />

Madagasikara<br />

BIBY MAMPINONO<br />

Ny fanisana natao dia niompana tamin’ny gidro sy<br />

ny ramanavy. Fito ny karazana gidro hita tao<br />

Tsitongambarika ka ny roa amin’ireo (Eulemur<br />

collaris sy Hapalemur griseus) dia tandimdomin-doza<br />

maneran-tany, iray tandindomin-doza ary ny roa<br />

kosa dia tsy mbola fantatra ka nokilasiana ho “tsy<br />

ampy fahalalana”. Na dia samy nahitana ireo<br />

karazana gidro fito ireo aza ny toerana telo<br />

nanaovana ny fikarohana dia Ivorona no tena<br />

mananana azy maro indrindra. Ireo karazana gidro<br />

ireo dia hita ihany koa tao amin’ny alan’Andohahela,<br />

manakaiky an’i Tsitongambarika, izay ahitana<br />

karazana valo.<br />

Karazana Ramanavy fito no hita tao ka ny roa<br />

dia tandimdomin-doza maneran-tany ary ny iray dia<br />

tsy ampy fahalalana. Tangoron-dramanavy, Pteropus<br />

rufus, karazana tandindomin-doza ivondronana<br />

ramanavy 2000 isa, no hita tao amin’ny toeramponenany<br />

efatra, indrindra fa tao Ivolo. Koa satria<br />

fohy loatra ny fotoana nanaovana ny fikarohana dia<br />

inoana fa mety mbola hahita karazana ramanavy<br />

maro hafa amin’ny fanisana manaraka.<br />

SAHONA SY REPTILIA<br />

Ireo tendrombohitr’Anosy dia iray amin’ireo faritra<br />

roa ahitana karazana sahona tandimdomin-doza<br />

maneran-tany betsaka indrindra ary ny faritr’Anosy<br />

dia anisan’ny manankarena reptilia indrindra eto<br />

Madagasikara. Ny fampitahana ireo reptilia sy<br />

sahona hita ao amin’ ny alan’i Tsitongambarika<br />

amin’ireo hita manodidina toy ny ala amin’ny sisindrano<br />

sy ny ala ao anatin’ny valan-javaboaharin’i<br />

Andohahela dia maneho fahasamihafana goavana.<br />

Ny fanisana natao tao Tsitongambarika, voafintina<br />

ato anatin’ity tatitra ity, dia nahitana karazana<br />

reptilia 70 sy karazana sahona 57. Karazana 12<br />

amin’ireo dia heverina fa tsy ho hita raha tsy ao<br />

amin’ny faritra Anosy, enina tandimdomin-doza<br />

maneran-tany, karazana efatra tandimdomin-doza<br />

ary enina tsy tsy ampy fahalalana.<br />

Na dia mbola tsy tanteraka aza ny fikarohana<br />

mahakasika ny famaritana ny karazana izay natao<br />

tamin’ny 2006, dia fantatra fa misy karazana<br />

sahona 4 sy androngo iray vaovao ho an’ny siansa<br />

hita tao.<br />

Ny nahitana ny karazana sahona sy reptilia, maro<br />

indrindra dia ao Ivorona sy Manatantely. Ireo<br />

karazana efa tandidomin-doza sy ireo mety ho vaovao<br />

kosa dia samy manana ny azy. Ankoatr’ Ivohibe sy<br />

Lakandava anefa, ny toerana rehetra ao dia<br />

mananana karazana manan-daja ho an’ny fiarovana<br />

ary koa tsy fahita raha tsy ao amin’izy ireo ihany.

VORONA<br />

Ao Tsitongambarika dia misy Karazana voron’ala<br />

amin’ny haabo iva maromaro toy ny Brachypteracias<br />

squamiger, Newtonia fanovanae, Hypositta<br />

corallirostris. Ao koa ny karazana izay fahita any<br />

amin’ny ala mando mbola tsara toy ny Mesitornis<br />

unicolor, Brachypteracias leptosomus, Xenopirostris<br />

polleni sy Neomixis flavoviridis. Nohon’ ny fananany<br />

karazana vorona tandidomin-doza sy miparitaka<br />

amin’ny faritra voafetra, Tsitongambarika dia<br />

voakilasy ho Faritra manan-danja ho fiarovana ny<br />

vorona (ZICO), izay nofaritan’ny <strong>BirdLife</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong>, eto Madagasikara (ZICOMA 1999).<br />

Ny fanisana vorona natao tao Tsitongambarika<br />

izay fintinina ato anatin’ity tatitra ity dia mampiseho<br />

97 karazana ka ny 57 (59%) amin’ireo dia tsy hita<br />

raha tsy eto Madagascar. Sivy amin’izy ireo dia<br />

tandimdomin-doza maneran-tany ary enina<br />

tandindomin-doza. Ny toerana manan-danja<br />

indrindra dia Ivorona sy Ivohibe.<br />

Tsy dia misy mahasamihafa azy amin’ny vorona<br />

hita ao amin’ny valan-javaboahary Andohahela izay<br />

manakaiky azy ny vorona ao amin’ny alan’ny<br />

Tsitongambarika. Ny fikarohana hafa hatao any<br />

amin’ny faritra avo, izay tsy mbola nisy fanisana koa<br />

dia mety mbola hampisongadina io fitoviana io.<br />

VITSIKA<br />

Ankoatry ny fanadihadiana notantanin’ny <strong>BirdLife</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong> dia nisy koa fanisana karazana vitsika<br />

izay nataon’ireo manam-pahaizana avy ao amin’ny<br />

California Academy of Science sy ny Madagascar<br />

Biodiversity Centre tao amin’ny alan’Ivohibe<br />

Tsitongambarika III. Vitsika mitotaly 105 karazana<br />

no voaiisa ary karazana 2 amin’ireo ihany no efa<br />

fantatra fa efa nisy teo an-toerana taloha.<br />

LANJA HAFA<br />

Ankoatra ny fananana lanja ho an’ny zavaboahary,<br />

ireo alan’ny Tsitongambarika koa dia manan-danja<br />

amin’ny tolotra ara-rohy voahary. Ny fanadihadiana<br />

ara-tsosialy sy ekonomika natao dia mampiseho fa<br />

io ala io dia loharam-bokatry ny ala goavana ho an’ny<br />

mponina eny ifotony. Toy ny kitay, saribao, fitaovana<br />

fanorenana, hena dia, zava-maniry fanao fanafody.<br />

Koa satria ny harikarena eny ifotony dia mifototra<br />

amin’ny hoenti-mivelona ary koa nohon’ ny tahampahatrana<br />

avodia avo dia miantehatra amin’ny<br />

vokatry ny ala ny mponina mba hamaly ny filàny<br />

andavan’andro. Ny fahaverezana sy fahapotehan’ny<br />

ala izany dia misy fiantraikany mafy amin’ny<br />

fahafaha-mivelon’ny mponina eny ifotony. Ny alan’i<br />

Tsitongambarika dia mandray anjara betsaka koa<br />

amin’ny fitehirizana karinbôna, ny fiarovana amin’ny<br />

asan’ny riaka ary amin’ny fiarovana ny ala mamefy<br />

ny renirano roa lehibe indrindra ao amin’ny faritra<br />

Ny Tsitongambarika alan’ i Tsitongambarika, Forest, Madagascar<br />

Madagasikara<br />

Anosy : Manampanihy sy Efaho. Ireo renirano lehibe<br />

ireo sy ny sampany no rano manondraka ny<br />

fambolena sy fampiasa ao an-tokatrano ho an’ireo<br />

mponina any atsinana amin’ny faritra. Ankoatr’izay,<br />

ny alan’i Tsitongambarika I dia miaro ny loharano<br />

ao amin’ny toerana fisintonan-drano ao Lakandava<br />

sy ny farihin’ny Lanirano izay miantoka 75% sy 25%<br />

ny rano ho an’ny tananan’i Tolagnaro. Manana lanja<br />

ara-koltoraly ho an’ny mponina ifotony koa ny alan’i<br />

Tsitongambarika. Misy sisan-tanàna manan-tantara<br />

maro, toerana masina, voly vary am-bohitra, toerampiraofan’ny<br />

biby ao anatin’ny faritra heverina ho ala<br />

arovana. Ankoatr’izay dia ireo toerana voahary<br />

rehetra toy ny renirano, honahona, farihy sy ny ala<br />

dia manan-danja tokoa ho an’ny nentim-paharazana,<br />

ny finoana sy ny maha izy azy ara-kolotsain’ny<br />

mponina eny ifotony.<br />

FIANTRAIKAN’NY ALA SY NY<br />

FIAROVANA AZY<br />

Ny fandripahana ny ala avy amin’ny fanaovana Tavy<br />

no manana fiantraikany lehibe indrindra amin’ny<br />

alan’i Tsitongambarika. Ny fandripahana sasany dia<br />

avy amin’ny afo tsy voafehy izay matetika natao ho<br />

fanadiovana ny toerana firaofan’ny biby sy fakana<br />

hazo. Na tsy dia misy fiantraikany firy aza ny<br />

fihazana sy ny fakana ny vokatra hafa ao an’ala dia<br />

manomboka mandany ireo loharanon-karena<br />

voajanahary sasany koa izany.<br />

Ankehitriny, ireo fomba heverina ho mahomby<br />

indrindra amin’ny fiarovana dia ny famindrampitantanana<br />

ny ala amin’ireo fikambanan eny<br />

ifotony. Mampalahelo anefa fa tsy mety amin’ny<br />

fomba fiasan’ny fikambanana ny fenitra koltoraly eny<br />

ifotony ary koa ireo fikambanana ireo dia toy ny<br />

voaterin’ny ONG sy ny fitondram-panjakana ka dia<br />

maro amin’izy ireny no efa mijoro nefa dia mbola<br />

osa. Raha toa ka mahita fomba fifanarahana<br />

amin’ny fiainan’ny fikambanana eny ifotony dia ny<br />

fanampiana miompana amin’ny fiofanana, torohevitra<br />

sy fanarahamaso no tokony homena azy ireo.<br />

Na izany aza, mety tsy ny fampiasana ireo<br />

fikambanana ireo no tetika mahoby amin’ny<br />

fitantanana ny ala. Mety ho ilaina ny mahita modely<br />

vaovao ho fiaraha-miasa amin’ny olona eny ifotony<br />

izay mifanaraka amin’ny lalàna ambanivohitra,<br />

fifandraisan’ny fahefana tsy mitovy, ny lanja sy<br />

ny finoana izay tena samihafa tokoa ho an’n<br />

mpisehatra ifotony, rezionaly sy nasionaly ary<br />

iraisam-pirenena. Na inona na inona anefa ny<br />

vahaolana ho raisina, ireo mpisehatra rehatra dia<br />

tokony handray andraikitra amin’ny fanampin’ezaka<br />

maharitra, amin’ny fikarohana sy fitantanana mba<br />

hiantohana ny fahatomombana’ny alan’i<br />

Tsitongambarika sy mba hikajina ireo zavaboahary<br />

tsy manampaharoa ireo, ireo fiveloman’ny mponina,<br />

ny fiainana sy ny kolotsaina ary mba hitohizan’ny<br />

tolotra ara-rohy voahary any atsimo atsinanan’i<br />

Madagasikara.<br />

5

Based on the findings of the report, a series of<br />

recommendations for those considering conservation<br />

intervention in the Tsitongambarika massif is<br />

given below. These recommendations are grouped<br />

in three categories—the first category includes<br />

recommendations on areas, sites and species deserving<br />

particular attention, the second and third focus on<br />

the kind of interventions that are needed to ensure<br />

that successful long-term biodiversity conservation<br />

is achieved without compromising the livelihoods and<br />

cultural values of local communities.<br />

PRIORITY AREAS, SITES AND SPECIES<br />

AT <strong>TSITONGAMBARIKA</strong><br />

■ Lowland humid evergreen forest is one of the most<br />

threatened vegetation types in Madagascar.<br />

Almost uniquely for humid forests in south-eastern<br />

Madagascar, Tsitongambarika includes significant<br />

areas below 400 m. These lowland areas (e.g.<br />

Bemangidy-Ivohibe) are particularly high priorities<br />

for conservation, especially given their importance<br />

for restricted-range plant species.<br />

■ Flying foxes provide significant ecosystem service<br />

benefits (pollination) as well as being a threatened<br />

species. Flying fox roosts (four have been identified<br />

in Tsitongambarika, notably at Ivolo) are<br />

priorities for site protection.<br />

■ Cultural sites warrant particular attention.<br />

Historical settlements, burial sites, and spiritual sites<br />

linked to natural features such as rivers, pools and<br />

cliffs have been identified in the forest, and are<br />

potentially of significant importance to local people.<br />

Since these will differ among clan territories<br />

particular attention will need to be paid to these in<br />

each area.<br />

■ For some taxonomic groups—e.g. reptiles and<br />

amphibians—it is difficult to select priority sites<br />

because globally threatened and potentially new<br />

species are distributed patchily (all sites except<br />

Lakandava and Ivohibe hold species of<br />

conservation concern not found at other sites).<br />

Similarly, many ecosystem service values (e.g. nontimber<br />

forest products, broader-scale services such<br />

as water purification) are dispersed throughout the<br />

forest. Consequently conservation management for<br />

the whole of Tsitongambarika is needed, not just<br />

for particular special sites or species.<br />

■ Priority species include globally threatened and<br />

restricted-range species. Tsitongambarika is home<br />

to many such species, including some Endangered<br />

6<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest, Madagascar<br />

■ RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

and site-endemic species which rank among the<br />

highest priorities.<br />

■ Species research should focus on information<br />

relevant to conservation management of priority<br />

species (e.g. distribution, threats, conservation<br />

actions needed and their effectiveness), taking into<br />

account that in many cases species will be most<br />

efficiently protected by measures aimed at<br />

preserving their habitat.<br />

■ Clarifying the status of species potentially new to<br />

science is a particular priority for species research.<br />

The surveys reported here found almost 70 plant<br />

species new to science and six reptile and<br />

amphibian species probably new to science.<br />

CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT NEEDS<br />

AT <strong>TSITONGAMBARIKA</strong><br />

■ Management activities are needed that will ensure<br />

persistence of viable populations of priority species,<br />

maintain the integrity of habitats, provide<br />

alternative livelihoods to local communities for<br />

foregone unsustainable forest use, and address<br />

specific threats identified in this report.<br />

■ Although some conservation activities have been<br />

implemented at Tsitongambarika, infrastructure<br />

and capacity are limited. Any future programme<br />

would need to make significant investment in<br />

infrastructure, training and capacity building,<br />

coupled with ongoing mentoring and support.<br />

■ To assist with planning future conservation or<br />

offset programmes, a short-term recommendation<br />

is to produce a short report detailing biodiversity<br />

values, costs and opportunities for each area<br />

(Tsitongambarika I, II and III).<br />

■ At present, the main mechanism for conservation<br />

is the transfer of forest management to local<br />

associations. However, since local cultural norms<br />

do not favour working in local associations and<br />

since these associations are seen as imposed by<br />

NGOs and the government, these local<br />

associations may not be the ideal mechanism for<br />

managing the forest, and there may be a need to<br />

look for a new model (and/or significantly adjust<br />

the current model) for working with local<br />

populations to manage the forest.<br />

■ In the long term, conservation management at<br />

Tsitongambarika will only be successful if it<br />

addresses the underlying causes of biodiversity loss.

The main pressure on Tsitongambarika is<br />

clearance for subsistence agriculture with<br />

additional major pressures from illegal timber<br />

harvesting and hunting. High rates of poverty and<br />

rapid population growth exacerbate this pressure.<br />

■ Sustainable livelihood programmes are needed that<br />

reduce human pressures on biodiversity and link<br />

biodiversity conservation with alternative<br />

appropriate benefits. Villagers will only be willing<br />

to conserve (which inevitably causes short-term<br />

natural resource use restrictions) if they receive<br />

commensurate benefits, such as support for rural<br />

development.<br />

ENSURING THAT LOCAL<br />

COMMUNITIES BENEFIT FROM<br />

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AT<br />

<strong>TSITONGAMBARIKA</strong><br />

■ Given that the Tsitongambarika Forest provides<br />

for local, regional, national, and international<br />

livelihoods and well being, research and<br />

programmes oriented on understanding and<br />

ensuring the continued supply of the diverse<br />

ecosystem services will be necessary.<br />

■ Given that the conservation and use of the forest<br />

are social endeavours at their core, future research<br />

and programmes need to focus on critical social<br />

research to increase our understanding of the local<br />

socio-cultural context including knowledge<br />

systems, traditions, and concepts and realities of<br />

forest management. It is only by better<br />

understanding these local socio-cultural contexts<br />

that we will be able to more effectively collaborate<br />

with the local forest managers, to manage and<br />

conserve the forest.<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest, Madagascar<br />

■ Given that there are very different and often<br />

contradictory perceptions of the forest held by<br />

stakeholders at the local, regional, national, and<br />

international levels, it will be important to recognise<br />

and address serious issues of unequal power<br />

relations, local rights, environmental justice, and<br />

fundamentally different value and belief systems<br />

among multiple stakeholders. This will be essential<br />

for conserving the Tsitongambarika forests for their<br />

unique biodiversity in a socially just way that also<br />

ensures local livelihoods, well-being and culture.<br />

■ Given the widely divergent stakeholder values<br />

regarding the biodiversity in the Tsitongambarika<br />

Forest, it may be necessary to broker agreements<br />

with communities to stop unsustainable use of<br />

forests in return for direct community development<br />

benefits. This will need to follow the principles of<br />

former, prior, and informed consent (FPIC). This<br />

will require culturally appropriate “deals”, rigorous<br />

external and local participatory monitoring, and<br />

adequate compensation.<br />

■ Given that the rural production systems and<br />

livelihoods in different areas around the forest are<br />

quite varied, programmes for forest conservation<br />

and livelihoods will need to be specifically tailored<br />

to local contexts and flexible enough to respond<br />

to local needs.<br />

■ Given that there are already more than 60<br />

community forest management groups in place<br />

throughout the forest, and that these are the de<br />

facto on-the-ground day-to-day managers of the<br />

forest, future efforts must ensure that these evolve<br />

into cultural appropriate operational and effective<br />

forest management mechanisms. The considerable<br />

support and attention that is necessary to achieve<br />

this should not be underestimated.<br />

7

Mifototra amin’ny voka-pikarohana avy amin’ity<br />

tatitra ity, dia misy tolo-kevitra maromaro izay<br />

napetraka mba ho an’ireo izay mety handray anjara<br />

amin’ny asa fiarovana ny alan’i Tsitongambarika,<br />

izay nosokajina telo. Ny sokajy voalohany dia ireo<br />

tolo-kevitra mahakasika ny faritra, toerana sy ny<br />

karazana ilaina fijerena manokana, ny faharoa sy ny<br />

fahatelo dia manasongadina ny karazana hetsika<br />

ilaina mba hiantohana ny fahombiazan’ny fiarovana<br />

ny zavaboahary amin’ny ho avy nefa tsy maningotra<br />

ny fahavelomana sy ny lanja ara kolotsain’ny<br />

fiarahamonina ifotony.<br />

IREO FARITRA, TOERANA SY<br />

KARAZANA LAHARAM-PAHAMEHANA<br />

AO <strong>TSITONGAMBARIKA</strong><br />

■ Ny ala mando tsy mihintsan-dravina amin’ny<br />

haabo iva dia iray amin’ny karazan-java-maniry<br />

tandidomin-doza indrindra eto Madagasikara.<br />

Amin’ny maha tsy manam-paharoa azy amin’ny<br />

ala atsimo atsinan’i Madagasikara, ny alan’i<br />

Tsitongambarika dia manana faritra lehibe<br />

amin’ny haabo ambanin’ny 400 m. Ireo faritra<br />

manana haabo iva ireo (oh Bemangidy-Ivohibe)<br />

dia laharam-pahamehana ho an’ny fiarovana<br />

noho ireo karazana zava-maniry manana<br />

fiparitahana voafetra ao amin’izy ireo.<br />

■ Ny ramanavy dia manana andraikitra tsara<br />

manokana ao anaty rohy voahary<br />

(fanaparitahana vovobony) na dia Karazana<br />

tandidomin-doza aza. Ireo toeram-pihantonan’izy<br />

ireo (misy efatra ao Tsitongambarika indrindra fa<br />

ao Ivolo) dia laharam-pahamehana amin’ny<br />

fiarovana ihany koa.<br />

■ Ireo toerana kolotoraly dia mila fiheverana<br />

manokana. Hita ao anaty ala ny tanàna manatantara,<br />

ny toerana fanaovana fomba sy<br />

fivavahana mifandraika amina singa natoraly toy<br />

ny renirano, honahona sy ny hantsana morondranomasina<br />

ary tena manan-danja tokoa ho<br />

an’ny mponina eny ifotony. Noho izy ireo<br />

samihafa isaky ny andiana foko dia ilaina ny<br />

fijerena manokana isaky ny faritra.<br />

■ Sarotra ny mamantatra ny toerana laharampahamehana<br />

ho an’ny fiarovana ny ny vondrona<br />

sasany toy ny sahona sy ny reptilia satria ireo<br />

karazana tandindomin-doza sy ireo karazana mety<br />

ho vaovao dia samy manana ny fiparitahany izay<br />

tsy mitovy (ireo toerana rehatra ankoatry<br />

Lakandava sy Ivohibe dia ahitana ireo karazana<br />

manan-danja amin’ny fiarovana manokana izay tsy<br />

8<br />

■ TOLO-KEVITRA<br />

Ny Tsitongambarika alan’ i Tsitongambarika, Forest, Madagascar<br />

Madagasikara<br />

hita any amin’ny toerana hafa). Toy izany koa ireo<br />

tolotra ara-rohy voahary manan-danja maro (toy<br />

ny vokatra tsy hazo, ireo tolotra avo lenta toy ny<br />

fanadiovana ny rano) dia miparitaka eran’ny ala.<br />

Noho izany dia ilaina ny miaro manontolo an’i<br />

Tsitongambarika fa tsy voafetra ho an’ny toerana na<br />

karazana voafaritra manokana fotsiny.<br />

■ Ny karazana manana lahara-pahamehana dia ireo<br />

karazana manana sata tandindomin-doza manerantany<br />

sy ny karazana manana fiparitahana voafetra.<br />

Tsitongambarika dia betsaka an’ireo karazana<br />

ireo, anisan’izany ny karazana efa ho lany<br />

tamingana sy ireo izay tsy fahita amin’ny toerankafa<br />

izay voakilasy ho anatin’ny laharampahamehana.<br />

■ Ny fikarohana mikasika ny karazana dia tokony<br />

hiompana amin’ireo fanadihadiana tena ilaina<br />

amin’ny fitantanana ny fiarovana ireo karazana<br />

manana laharam-pahamehana (oh Ny fiparitahana,<br />

ireo loza mitatao, ireo fepetra fiarovana tokony<br />

ho raisina sy ny fahombiazany) ireo, nohon’ny<br />

fahatsapana tamin’ny tranga hafa maro fa voaro<br />

kokoa ny karazana izay ampiharana fiarovana<br />

mikendry fikajiana ny toeram-ponenany.<br />

■ Ny fandalinanana ny satan’ireo karazana<br />

heverina ho vaovao eo amin’ny siansa dia<br />

laharam-pahamehana manokana ho an’ny<br />

fikarohana ny karazana. Ireo fanadihadiana<br />

naseho teto dia nanambara fa 70 ny karazana<br />

zava-maniry vaovao ary 6 kosa karazana ho an’ny<br />

sahona sy ny reptilia.<br />

NY TOKONY HATAO HO AN’NY<br />

FITATANANA NY FIAROVANA AO<br />

<strong>TSITONGAMBARIKA</strong><br />

■ Ny asa fitantanana ilaina dia ireo izay miantoka<br />

ny faharetan’ny andiany tokony ho velona ho<br />

an’ireo Karazana manana laharam-pahamehana,<br />

mitana ny fahatsaran’ny toeram-ponenany ary<br />

manolotra solona fomba fivelomana ho an’ny<br />

mponina ifotony ho fanitsiana ny fampiasana tsy<br />

maharitra ireo ala, ary mijery manokana ireo loza<br />

mitatao voatanisa tato amin’ity tatitra ity.<br />

■ Na dia eo aza ireo asa fiarovana efa natomboka<br />

tao Tsitongambarika, ny foto-drafitr’asa sy ny<br />

fahaiza manao dia tsy ampy. Ny lamin’asa rehetra<br />

amin’ny ho avy dia tokony hampiasa vola betsaka<br />

amin’ny lafiny foto-drafitr’asa , fampiofanana sy<br />

fanamafisana fahaiza-manao arahina fanarahamaso<br />

sy fanampiana mitohy.

■ Hanampiana ny rafitr’asa fiarovna na ny<br />

lamin’asa onitra amin’ny ho avy dia misy fepetra<br />

tokony hatao avy hatrany dia ny famoahana<br />

tatitra fohy mikasika ireo lanja, ireo teti-bidy sy<br />

ireo zay tsara fanararaotra ho an’ny faritra<br />

tsirairay(Tsitongambarika I, II, III).<br />

■ Ankehitriny, ny fomba fiarovana misongadina dia<br />

ny Famindram-pitantanana ny ala amin’ireo<br />

fikambanan eny ifotony. Koa satria tsy mety<br />

amin’ny asa ao amin’ny fikambanana ny fenitra<br />

kolotoraly eny ifotony ary koa ireo fikambanana<br />

ireo dia toy ny voabaikon’ny ONG sy ny<br />

fitondram-panjakana, dia heverina fa tsy fomba<br />

idealy ny fampiasana ny fikambanana : tsy maintsy<br />

heverina ny hahita modely vaovao (sy/na hanova<br />

am-pitandremana ny modely efa misy ) hiarahamiasa<br />

amin’ny mponina mba hiarovana ny ala.<br />

■ Any aoriana any, ny fitantanana ny fiarovana an’i<br />

Tsitongambarika dia tsy hahomby raha tsy<br />

mahakasika ireo tena antony fototra mahatonga<br />

ny fahaverezan’ny zavaboahary. Ny tena tsindry<br />

mahazo an’i Tsitongambarika dia ny<br />

fandringanana ala hanaovana fambolena<br />

hivelomana, ampian’ny tsindry fanampiny sady<br />

manan-danja mifandraika amin’ny fihazana sy ny<br />

fakana tsy ara-dalana ireo hazo. Ny taha avon’ny<br />

fahantrana sy ny fitombon’’ny mponina dia vao<br />

maika manampy trotraka ireo tsindry ireo.<br />

■ Ny fisian’ny lamin’asa ho amin’ny fahafahamivelona<br />

maharitra dia ilaina mba hampihenana<br />

ny tsindry avy amin’olombelona amin’ny zavaboahary<br />

ary hampifandray ny fiarovana ny zavaboahary<br />

sy ny famoronana solon’antompivelomana<br />

mety. Tsy afaka hiaro ny voahary ny<br />

mponina (izay tsy azo ialana ny hisian’ny famerana<br />

ao anatin’ny fotoana fohy) raha tsy mahazo<br />

tombotsoa mifanaraka amin’izany toy ny<br />

fanampiana amin’ny fampandrosoana<br />

ambanivohitra.<br />

NY FIARAHA-MONINA ENY IFOTONY<br />

DIA MAHAZO TOMBONY AMIN’NY<br />

FIAROVANA NY ZAVA-BOAHARY AO<br />

<strong>TSITONGAMBARIKA</strong><br />

■ Koa satria ny alan’i Tsitongambarika dia<br />

manome fomba ahafaha-mivelonaho an’ny eny<br />

ifotony, rezionaly, nasionaly sy iraisam-pirenena,<br />

ny fikarohana sy ny lamin’asa ahazoana antoka<br />

sy ahafantarana fa ilaina ny tolotra rohy voahary<br />

samihafa dia tena ilaina tokoa.<br />

■ Koa satria ny fiarovana sy ny fampiasana ny ala<br />

dia mifototra indrindra amin’ ny ezaka aratsosialy,<br />

ny fikarohana sy ny lamina’asa amin’ny<br />

Ny Tsitongambarika alan’ i Tsitongambarika, Forest, Madagascar<br />

Madagasikara<br />

ho avy rehetra dia tokony hanasongadina ny<br />

fanadihadiana matotra mikasika ny ara-tsosialy<br />

izay mikendry ny fahazahoantsika bebe kokoa ny<br />

toe-draharaha ara kolotoraly sy soasialy eny<br />

ifotony, ao anatin’izany ny fahalalana, ireo nentimpaharazana<br />

ary ireo endrika sy zava-misy marina<br />

mifandraika amin’ny fitantananana ny ala. Ny<br />

fahazahoana tsara ireo endrika kolotoraly sy<br />

sosialy eny ifotony mantsy no ahafahantsika<br />

manana fiaraha-miasa mahomby miaraka<br />

amin’ireo mpitantana ala sy hitantanana ary<br />

hiarovana ny ala.<br />

■ Koa satria ny fahatsapan’ireo andaniny sy<br />

ankilany mpifanaiky eny ifotony, rezionaly,<br />

nationaly sy iraisam-pirenena dia tena samy hafa<br />

ary mifanohitra aza matetika dia tena ilaina<br />

arak’izany ny mahalala sy mijery ireo singa<br />

fototra toy ny fifandraisan’ny fananam-pahefana<br />

tsy mitovy, ny zo eny ifotony, ny fahamarinana aratontolo<br />

iainana, ary ny fahasamihafana fototra eo<br />

amin’ny lanja sy ny finoan’ny mpiray tan-tsoroka<br />

tsirairay. Ireo dia zava-dehibe amin’ny fiarovana<br />

ny alan’i Tsitongambarika, mba hiarovana io<br />

zava-boahary tokana aman-tany io amin’ny<br />

alalan’ny fiantohana ny fahaveloman’ny olona sy<br />

ny fiadanany ary ny kolo-tsaina.<br />

■ Eo anatrehan’ny karazana lanja ananan’ny<br />

andaniny sy ny ankilany mpifanaiky tsirairay<br />

mikasika ny zava-boahary ao Tsitongambarika<br />

dia tokony ilaina ny mandamina ny fifanarahana<br />

amin’ny rehetra mba hisorohana ny fampiasana<br />

tsy maharitra ny ala ho takalon’ny tombotsoa<br />

mivantana ho amin’ny fampandrosoana ny<br />

vahoaka. Amin’izany dia tokony harahina ny<br />

foto-kevitra (CLPE) fanekena malalaka, mialoha<br />

sady mazava . Mitaky fifanarahana ara-kolotsaina<br />

mifandrindra, fanaraha-maso iraisana avy ivelany<br />

sy ifotony matotra ary onitra azo ekena tsara izany.<br />

■ Nohon’ny fahasamihafana misy amin’ny fomba<br />

fahafaha-mivelona eny ambanivohitra ao amin’ireo<br />

faritra tsirairay manodidina ny ala, ireo lamin’asa<br />

amin’ny fiarovana ny ala sy ny fomba<br />

fiveloman’ny olona dia tokony hifanaraka tsara<br />

amin’ny zava-misy ary koa afaka amboarina mba<br />

hamaly ireo hetahetan’ireo mponina eny ifotony.<br />

■ Koa satria efa misy Fikambanana mpitantana ala<br />

60 isa ao ary izy ireo dia mpitantana isan’andro<br />

ny ala, ny hetsika rehetra amin’ny ho avy dia tsy<br />

maintsy hiantoka ny fivoaran’ireo vondrona ireo<br />

ho amin’ny fomba fitantanana mihodina sy<br />

mahomby ireo ala izay mifanentana tsara amin’ny<br />

kolotsaina. Tsy tokony hatao ambanin-javatra ny<br />

fanampiana sy ny fiheverana manokana<br />

mikasika ny fomba hatao mba hahatratrarana io<br />

tanjona io.<br />

9

BACKGROUND<br />

The Tsitongambarika forests comprise three forest<br />

management units (termed Tsitongambarika I, II and<br />

III) in Anosy Region, south-eastern Madagascar.<br />

These forests lie along the Vohimena mountains,<br />

which run north from Tolagnaro (Fort Dauphin) for<br />

a distance of around 100 km. These mountains run<br />

parallel to the Anosyenne mountains, where<br />

Andohahela National Park is situated. The Vohimena<br />

mountains reach a maximum altitude of 1,358 m,<br />

while the Anosyenne mountains are significantly<br />

higher, reaching a maximum altitude of 1,956 m.<br />

The Tsitongambarika forests are characterised by<br />

a mountainous relief, with steep slopes rising abruptly<br />

from the narrow coastal plain. Generally speaking,<br />

the soils of Tsitongambarika comprise laterites and<br />

ferralites, deposited on Pre-Cambian gneiss and<br />

granitic rocks (Bourgeat 1972). The soils are generally<br />

rich, humus-bearing and of varying depth; rock<br />

outcrops are frequent.<br />

Tolagnaro experiences a tropical climate, with an<br />

average annual rainfall of 1,679 mm, equivalent to<br />

140 mm per month. There are nine perhumid months<br />

per year but no dry months. Average annual<br />

temperature is 23.4°C, with relatively little seasonal<br />

variation. There appears to be a north-south gradient<br />

in rainfall along the Tsitongambarika forests, with<br />

Manantenina (near the northern end) receiving an<br />

average of 3,000 mm per year, compared with<br />

Nahampoana (near the southern end), which receives<br />

only 2,130 mm annually (Paulian et al. 1973). Moist<br />

easterly winds provide orographic rainfall on the<br />

windward slopes of the Vohimena and Anosyenne<br />

chains, leading to the development of humid forest;<br />

this contrast sharply with the semi-arid climate<br />

prevalent to the west of the Anosyenne mountains.<br />

Following the classification of Humbert (1955),<br />

the Tsitongambarika forests comprise humid forest<br />

at low altitude (0–800 m) and humid forest at medium<br />

altitude (800–2,000 m asl) of the eastern Madagascar<br />

Region. Humid forest at low altitude is the most<br />

endangered vegetation type in Madagascar (Langrand<br />

1990), particularly as a result of clearance for tavy<br />

(shifting cultivation) and exploitation for fuelwood.<br />

According to the results of the Inventaire Ecologique<br />

et Forestier National, in the mid 1990s, there were only<br />

around 2 million ha of lowland dense forests<br />

(including Sambirano formations) with little or no<br />

modification, plus around 500,000 ha in a degraded<br />

or secondary condition (Dufils 2003). According to<br />

Langrand (1990), the only large tracts of lowland<br />

humid forest remaining “are those surrounding the<br />

10<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest, Madagascar<br />

■ Chapter 1: OVERVIEW OF THE BIOLOGICAL<br />

IMPORTANCE OF <strong>TSITONGAMBARIKA</strong> <strong>FOREST</strong><br />

ANDREW W. TORDOFF<br />

Bay of Antongil and south of Mananara”.<br />

Nevertheless, significant areas of lowland humid<br />

forest can still be found in south-eastern Madagascar,<br />

most notably the Tsitongambarika forests. Until<br />

recently, these forests had been the focus of little<br />

biodiversity study, and recognition of their biological<br />

importance was limited.<br />

THE SURVEYS<br />

During 2005 and 2006, the Tsitongambarika forests<br />

were the focus of a series of biodiversity surveys<br />

conducted by a team of Malagasy and international<br />

scientists from Missouri Botanical Garden, Rio Tinto<br />

QMM (QIT Madagascar Minerals, QMM), and two<br />

Malagasy NGOs: Asity Madagascar and<br />

Madagasikara Voakajy. These surveys were<br />

coordinated by <strong>BirdLife</strong> <strong>International</strong>, and funded<br />

through <strong>BirdLife</strong>’s partnership with Rio Tinto, a<br />

leading mineral resources company, which is the<br />

major shareholder in Rio Tinto QMM.<br />

The surveys highlighted the biological importance<br />

of Tsitongambarika. In particular, they revealed that<br />

the Tsitongambarika forests include some of the most<br />

intact areas of primary humid forest remaining at very<br />

low elevations in south-eastern Madagascar, and<br />

indicated that they are floristically and faunistically<br />

distinct from lowland humid forests elsewhere in the<br />

country.<br />

VEGETATION AND FLORA<br />

Although the Tsitongambarika forests reach a<br />

maximum altitude of 1,358 m, they contain significant<br />

areas below 800 m, and, almost uniquely for humid<br />

forests in south-eastern Madagascar, include sizeable<br />

areas below 400 m. Although the humid forests of<br />

south-eastern Madagascar are south of the Tropic of<br />

Capricorn, they are typically tropical in structure and<br />

composition (Goodman et al. 1997). Indeed, at 25°S,<br />

Tsitongambarika is one of the lowest latitude<br />

“tropical” humid forests in the Old World (Goodman<br />

et al. 1997).<br />

While eastern humid forest is the most abundant<br />

natural forest formation in Madagascar, about 80%<br />

of it is mid-altitude forest between 800 and 1,500 m,<br />

and relatively little remains at low elevations (Morris<br />

and Hawkins 1998). In south-eastern Madagascar,<br />

lowland forest on lateritic soils is thought to have been<br />

previously extensive but little now remains, as a result<br />

of clearance for shifting cultivation (Goodman et al.

Map 1. Topographic map of vegetation<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest, Madagascar<br />

11

1997). It is not clear why the Tsitongambarika forests<br />

have survived while others growing on similar terrain<br />

have been cleared, although the fact that local people<br />

did not practice shifting cultivation until recently may<br />

offer a partial explanation (Nicoll 2003). This may<br />

reflect a relative unsuitability of the area for shifting<br />

cultivation, due to some underlying feature of climate,<br />

topography and/or geology.<br />

Three vegetation and flora surveys were conducted<br />

by the botanical team during November 2005,<br />

February 2006 and May 2006. These surveys focused<br />

on Bemangidy-Ivohibe Forest in Tsitongambarika<br />

III. This area of forest is notable because of the<br />

presence of relatively undisturbed humid forest at<br />

altitudes below 100 m.<br />

To date, in the Bemangidy-Ivohibe Forest and<br />

other sites in Tsitongambarika, nearly 600 species<br />

have been identified in 366 genera and 121 families,<br />

suggesting that the total flora of Tsitongambarika<br />

probably includes well over 1,000 species. Given the<br />

relative lack of previous botanical collections from<br />

lowland humid forests in south-eastern Madagascar,<br />

it is reasonable to expect that further surveys will<br />

reveal yet more new species.<br />

Newly described plant species from<br />

Tsitongambarika include Gnidia razakamalalana, a<br />

treelet in the Thymelaeaceae family, collected at 90<br />

m altitude. Based on a known area of occupancy of<br />

less than 10 km 2 , this species has been provisionally<br />

assessed as globally Endangered (P. Lowry in litt.<br />

2007). The new discoveries also include three species<br />

in the Araliaceae family: Polyscias bemangidiensis, an<br />

understorey shrub to treelet that is reasonably<br />

common at Bemangidy-Ivohibe Forest; Polyscias<br />

emargiata, a small tree known only from a single<br />

population restricted to a granite slab at c.100 m<br />

altitude; and Schefflera bemangidiensis, a slender<br />

forest tree known only from Bemangidy-Ivohibe<br />

Forest (P. Lowry in litt. 2007).<br />

These species are currently known only from<br />

Tsitongambarika. While some of them may have had<br />

wider distributions previously, the extensive loss of<br />

lowland humid forest from other parts of southeastern<br />

Madagascar suggests that at least some of<br />

them may now be restricted to the Tsitongambarika<br />

forests.<br />

MAMMALS<br />

The mammal surveys recorded seven bat species,<br />

including four species of conservation concern:<br />

Madagascar Flying-fox Pteropus rufus (Vulnerable),<br />

Madagascan Fruit Bat Eidolon dupreanum<br />

(Vulnerable), Peter’s Sheath-tailed Bat Emballonura<br />

atrata (Vulnerable) and Madagascan Rousette<br />

Rousettus madagascariensis (Near Threatened). The<br />

population of Pteropus rufus is particularly<br />

significant, numbering around 2,000 individuals<br />

divided among four roosts. Also of note, Eidolon<br />

dupreanum was hitherto unknown from Anosy<br />

12<br />

Tsitongambarika Forest, Madagascar<br />

Region. Considering the relatively short survey<br />

period, it is likely that further survey effort at<br />

Tsitongambarika would reveal additional bat<br />

species.<br />

In addition to bats, the mammal surveys also<br />

focused on lemurs. Seven species of lemur were<br />

identified, comprising two diurnal species (Collared<br />

Brown Lemur Eulemur collaris and Grey Gentle<br />

Lemur Hapalemur griseus) and five nocturnal species<br />

(Brown Mouse-lemur Microcebus rufus, Greater<br />

Dwarf Lemur Cheirogaleus major, Southern Woolly<br />

Lemur Avahi meridionalis, Greater Sportive Lemur<br />

Lepilemur mustelinus and Aye-aye Daubentonia<br />

madagascariensis). Two of these species (Collared<br />

Brown Lemur and Grey Gentle Lemur) are globally<br />

threatened. All of the lemur species recorded at<br />

Tsitongambarika can also be found at the nearby<br />

Andohahela National Park, where eight species have<br />

been recorded (Feistner and Schmid 1999).<br />

REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS<br />

The Global Amphibian Assessment revealed that the<br />

Anosy (including Vohimena i.e. Tsitongambarika)<br />

mountains are one of the two areas in Madagascar<br />

with the highest number of globally threatened<br />

amphibian species, the other one being the northern<br />

and north-eastern highlands (Andreone et al. 2005).<br />

The Anosy Region is also one of the richest in<br />

Madagascar in terms of number of reptile species,<br />

with a number of species not known from elsewhere<br />

in the country.<br />

The reptile and amphibian surveys conducted<br />

during 2006 focused on two lowland humid forest sites<br />