Changing Times: A Cultural Snapshot of the Edwardian Era

March 14, 2016

When you see the fashions on display in Dressing Downton™: Changing Fashion for Changing Times, you step into a broader cultural tale about the vast changes sweeping the world in the first decades of the 20th century.

Everything that once seemed permanent began to change. Corsets started disappearing from women’s wardrobes. The indomitable aristocratic elite began struggling to make ends meet. A younger generation redefined everything from good manners to falling in love. This tension between the traditional and the new forms the crux of the drama of Downton Abbey®, as seen through the lives of the Earl and Countess of Grantham, their daughters, and their domestic servants. And the greatest share of the changes took place in the lives of women. From going out with men unchaperoned to trying out cigarettes, women took for themselves a greater share in the public sphere.

Let’s go back to that tumultuous time and explore a few of the cultural phenomena of the 1910s and 20s. Here’s what everyone was talking about, both in England, the world of Downton Abbey,and here at home in Chicago.

Loosen That Corset!

In the early 20th century, women’s fashion was perhaps the biggest sign that things were changing. Bodices relaxed, waists dropped, and hems rose. Clothes became looser, freer, and less restrained with every passing year, and paralleled the increasing freedom women had in society. In the exhibition, you’ll see how the dresses of Downton Abbey’s younger generation (especially Lady Sibyl, Lady Edith and Lady Rose) reflected these changing times, while women like the Dowager Countess adhered firmly to tradition.

For more on the latest fashions, take a look at a blog post from our last exhibition about the harmony of artistic clothing and jewelry in the early 20th century.

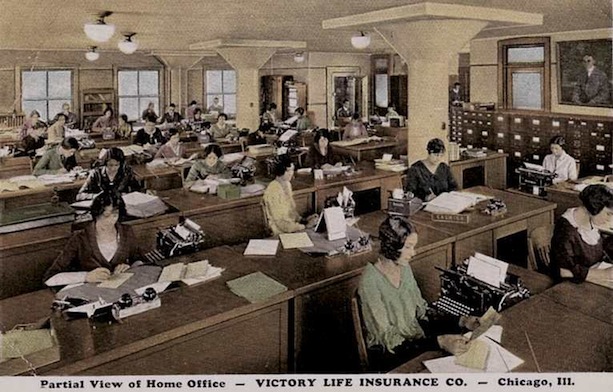

Working Women

It was Lady Edith who dared to begin work outside the home in Season 3 of Downton Abbey. It’s 1920, and she takes a job as a newspaper columnist. It scandalizes her elders, who expected her to marry a well-heeled man and make her home her domain. In their eyes, her role should have been as a high society hostess, with entertaining and domestic servants her most important callings.

While women of the lower classes worked in factories or in large country houses like Downton during the Victorian and Edwardian eras, a new phenomenon was the necessity or desire of a woman of the middle and upper classes to work.

Firstly, the war years demanded practicality. In America, England, and the Continent, women went to work because they were needed there while men fought on the front lines. And when the war was over, recession meant that many of them wanted to stay and continue earning with newfound technical skills.

Work was also then, as today, one of the central battlegrounds for another type of war—one for women’s equal rights. Lady Edith represents a new wave of women who wanted to work beyond the domestic spheres previously reserved for them, whether to exercise creativity, earn better money independently of their husbands or fathers, or contribute to the public good of society.

Women working in the Leys Malleable Castings Company in England, 1930s. Image via The Daily Mail.

Women working in the Leys Malleable Castings Company in England, 1930s. Image via The Daily Mail.Meet Me at the Movies

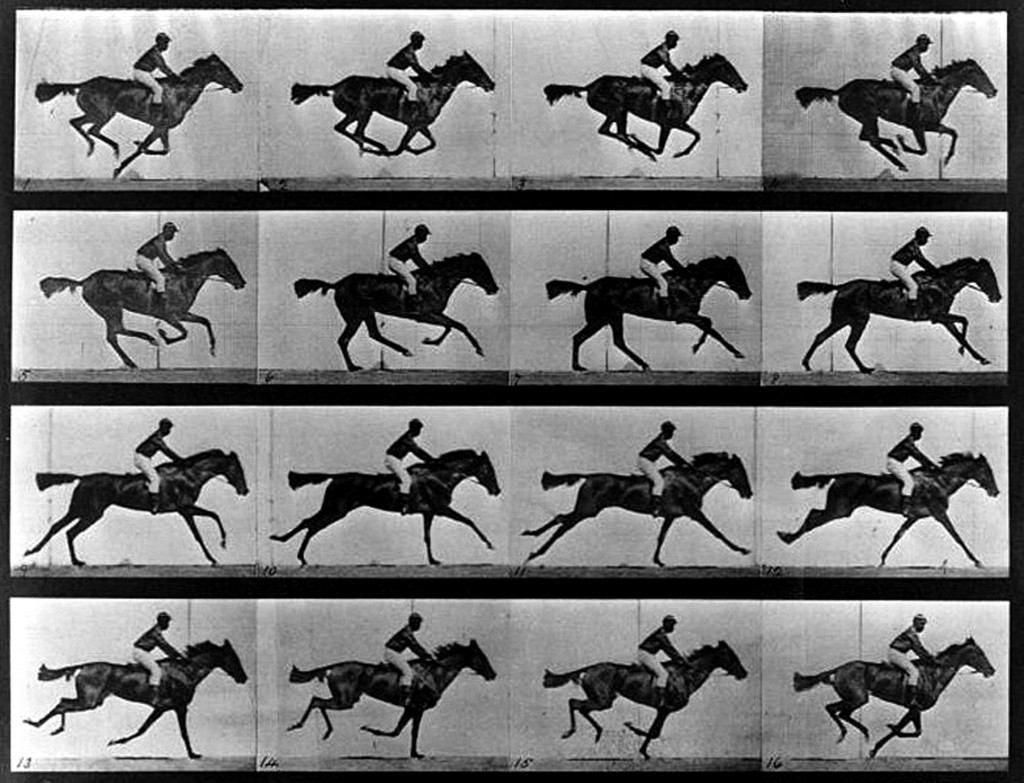

English photographer Edward Muybridge’s studies of a horse in motion, 1878.

English photographer Edward Muybridge’s studies of a horse in motion, 1878.The first famous moving image was captured by British-American scientist Edward Muybridge in the 1870s. He set up cameras along a racetrack and put together second-by-second snapshots of a galloping horse. But a movie would need many more pictures than Muybridge took, and a handful of ingenious inventors around the world made real “cinématographe” possible in the late 19th century.

At first England and France led the world in early filmmaking. The French magician Georges Méliès famously made the leap from early documentary-style shorts to narrative filmmaking, and enjoyed enormous popularity with the film Le Voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon) in 1902.

Back in the US, Edwin Porter’s twelve-minute film, The Great Train Robbery (1903), was the industry’s first big blockbuster. It ushered in the silent film era, as investors began confidently building movie theaters for this new American pastime. Silent film showings often featured live music just as theatrical plays would have, while the narrative was expressed through mime or notecards.

As the European countries were strained by impending war, America took first place in the film industry. Chicago was filled with avid moviegoers from the start. The first issue of Chicago-based magazine The Show in 1907 proclaimed this city as a world leader in moving picture rental and patronage, and Chicago possibly had more movie theaters per capita than any other US city. The 1910s and 20s saw the construction of gorgeous “movie palaces,” such as The Chicago Theatre, the Oriental, and the Uptown, some of which are still preserved today.

Silent film star Buster Keaton in The General (1926)

Silent film star Buster Keaton in The General (1926)Some of the most famous films from the era are Nosferatu, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and Birth of a Nation, and The General. The era’s stars, from Charlie Chaplin to Louise Brooks, Greta Garbo, and Buster Keaton, are still remembered.

“Lucky” Girls

While smoking cigars or cigarettes was acceptable for men before the early 20th century, a woman smoking was a severe faux pas. A 1901 article in The New York Times warned that the habit among women was “a menace in this country.” It was a social rule so powerful it even leaked into law. One New York policeman, spying a woman smoking in a car in 1904, pulled the automobile over and ordered her to put the cigarette out. The gender division was even built into Victorian architecture, with a separate smoking room for men to enjoy their recreational activity together while women retreated to the drawing room or parlor.

But in the early 20th century, along with increased educational opportunities and the suffrage movement, modern women started crossing that divide. Some embraced smoking as a symbol of freedom—a freedom to enjoy men’s freedoms. A march in New York in 1929, an event in which the American Tobacco Company participated through the early public relations genius Edward Bernays, saw women marching for equality with cigarettes in hand. “Group of Girls Puff Cigarettes as a Gesture of ‘Freedom’,” the headline read.

Advertisers started targeting this untapped market. Lucky Strikes featured glamorous illustrations of Miss America, or encouraged women to keep slim by reaching “for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet.”

All That Jazz

In Season Four of Downton Abbey, rebellious Lady Rose falls for the jazz entertainer Jack Ross. His character is based on a number of jazz stars whose careers took them on a tour of Europe, such as Leslie “Hutch” Hutchinson or Will Marion Cook. With its emphasis on spontaneous forms, jazz was the perfect antidote for the stuffy, formal life so many young people were trying to shed.

Resources

Downton Abbey, PBS Masterpiece.

Elliot, Rosemary Elizabeth. “‘Destructive but sweet’: cigarette smoking among women 1890-1990,” University of Glasgow, October 2001.

“Film,” The Encyclopedia of Chicago.

“History of the Motion Picture,” Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Hudson, Pat. “Women’s Work,” BBC, March 29, 2011.

Lee, Jennifer. “Big Tobacco’s Spin on Women’s Liberation,” October 10, 2008.

Myers, Marc. Why Jazz Happened, University of California Press, 2013.

Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising, “Tobacco Advertising Themes: Targeting Women”

Striking Women, “Women and Work: The Interwar Years, 1918-1939.”