Blotter art

Blotter art is an art form printed on perforated sheets of absorbent blotting paper infused with liquid LSD. The delivery method gained popularity following the banning of the hallucinogen LSD in the late 1960s. The use of graphics on blotter sheets originated as an underground art form in the early 1970s, sometimes to help identify the dosage, maker, or batch of LSD.

Images may be of various sizes but sheets are often 7.5-inch (190 mm)-square and perforated into a 30 by 30 grid. Individual pieces, separated along the perforations, were sold as "hits", with a carefully calculated dosage in micrograms, so users could plan the intensity of their "trip". Blotter art also appears on blotter paper carrying other potent substances, and on undipped (drug-free) sheets.

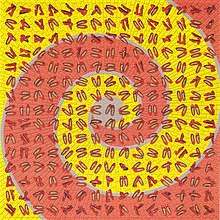

Blotter art frequently incorporates themes common to psychedelic art, using bright, contrasting colors and repeating patterns in its designs. Cartoon characters were often exhibited, and many examples contain religious and mystical imagery or pay homage to figures in the psychedelia subculture.

Blotter art has been exhibited at art galleries and undipped blotter is often sold online. San Francisco collector Mark McCloud founded the Institute of Illegal Images, which includes over 33,000 sheets of blotter art.

History[edit]

LSD and blotting paper[edit]

Early in its history, LSD was distributed in liquid form, sometimes applied to sugar cubes, or in pills, capsules, or gelatin "window panes". After LSD became illegal, first in California in 1966, the use of blotter paper as a medium became more common.[1][2] In the United States Supreme Court case Chapman v. United States, the court found that Congress had intended to include the weight of the carrier medium for LSD in its sentencing guidelines, regardless of whether it was in liquid form, on blotting paper, or the much heavier sugar cubes. The vastly disparate penalties for possessing LSD affected the choice of medium for the acid-taking community.[3][4]

Aside from the legal ramifications, a machinist who had built specialized pill presses for the underground in the United States died in the late 1970s. Due to these factors, acid producers largely switched to blotter paper which had the advantage of being easily sent through the mail.[5] By the end of the decade, blotter had become the standard medium for distribution.[a][5] Later blotter art existed independent of LSD production.[2]

Blotter designs as art[edit]

The production of blotter acid with graphics started as early as 1970.[5] Symbolic pictures were sometimes added to indicate the origin of the LSD. Designs printed on blotter paper can serve to identify dosage strengths, different batches, or makers.[6] As designs became more creative, blotter art became a folk and underground art form, drawing on an art vocabulary borrowed from psychedelic art and underground comix.[5][2] Early blotter acid seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration depicted the Robert Crumb character Mr. Natural.[5] LSD is sometimes branded under a particular name, and individual producers may use blotter art designs,[4] which serve as a sort of calling card. In one instance, a chemist who went by "Bill" used the Saturday Night Live character Mr. Bill as his signature design.[7]

Works of psychedelic art have often been reappropriated for use as blotter art. The Mati Klarwein-designed cover of the 1970 Santana album Abraxas, for one, was used as a blotter art design. Other artworks that became blotter art were Frank Kozik's Tribute to Preston Blair, Stanley Mouse's Flying Eyeball, and Reverend Samuel's Lucifer.[4] Blotter art has also appropriated older artworks such as The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch.[7]

An acid dealer from Golden Gate Park who was interviewed by the San Francisco Chronicle in 1979 thought that widespread interest in kung fu was responsible for Asian symbology in early blotter designs, including yin-yang symbols, Chinese dragons and stars. Another popular design at the time was rainbow blotter.[5]

Themes and imagery[edit]

Blotter art is a type of psychedelic art and incorporates many of its elements, such as color palettes reminiscent of 1960s art and the use of bright, contrasting colors.[8] Blotter art emphasizes psychedelic themes,[6] frequently incorporating repeating patterns in its designs, such as fractal, paisley, moiré, or kaleidoscopic patterns.[4] While early blotter art designs could be simple repetitions of a smiley face or a single word such as PURE[1] or YES,[7] the subject matter soon veered toward the fantastic, surreal, and metaphysical.

Cartoon and comic book characters have been consistently popular subjects throughout the history of blotter art. Early subjects were Felix the Cat, Mighty Mouse, Goofy, Mickey Mouse as the Sorcerer's Apprentice from Fantasia,[4] and the Cheshire Cat from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.[9] Designs changed according to the era, and later subjects were Bart Simpson, Beavis and Butt-Head,[10] characters from South Park, and SpongeBob SquarePants.[11] A 1991 report from The Army Lawyer noted that tabs of acid were imprinted with designs of the Lucky Charms breakfast cereal mascot or Mickey Mouse.[3] Painter Randall Roberts' psychedelic portrait of Homer Simpson was a popular blotter design in 2018.[12]

Blotter art often incorporates religious, mystical and occult symbology, such as pentagrams, a Tetragrammaton, Knights of Malta shields, the Giza pyramids, and UFOs.[4] Religious figures such as Jesus, Buddha,[8] and the Dalai Lama have also been depicted in blotter art.[11] At the 2010 Boom Festival, there was blotter with a Shiva image.[13] Other designs used new age iconography, such as astrological signs.[7]

Blotter art often pays homage to figures within the psychedelic movement, such as Timothy Leary, Albert Hofmann, and the Furthur bus used by Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters.[1] Early blotter art often employed Grateful Dead symbols such as bears and the Steal Your Face lightning bolt-skull logo.[1] One piece of blotter art featuring cartoon blue unicorns commemorates the Blue Unicorn, a hippie and Beat coffeehouse in San Francisco.[14]

Blotter art also features animals and political symbols,[15] like the peace dove, dolphins, John Lennon,[16] or the anarchist Circle-A symbol.[8]

Blotter art sometimes bordered on the satirical, depicting figures such as Mikhail Gorbachev on "Gorby acid" and depictions of a sheet with a red background with a miniature Seal of the Federal Bureau of Investigation on each tab.[4][14] An example of blotter art from 1987 depicted pink flamingos[7] while another from 2015 depicted characters from the Breaking Bad television series.[17]

Blotter art collecting[edit]

While blotter art originated in the early 1970s, most sheets of acid from the period were not preserved due both to their status as perishable commodities and their illegality. San Francisco artist Mark McCloud was an early collector and popularizer of the art. He matted and framed blotter sheets he had collected, sometimes obtaining undipped, LSD-free sheets from acid dealers.[18] He exhibited his collection in the mid-1980s and in 1987 won second place at the San Francisco County Fair for his exhibition, which was described as "unusual but timely".[4] His collection includes over 33,000 sheets of blotter.[2] 400 framed sheets of blotter art are displayed in his San Francisco home, which doubles as a gallery for blotter art named the Institute of Illegal Images.[18]

In 1987, McCloud attended an exhibition by Alex Grey, a painter known for his spiritual and psychedelic works. He purchased Grey's Purple Jesus painting for $1000. The painting depicts a purple crucified Jesus with visible internal anatomy, surrounded by a "flowering halo of blotter acid". McCloud made a print of the work, and produced around 3,000 blotter sheets that he then distributed. Later infused with LSD, the resulting Purple Jesus blotter was popular in California in the early 1990s. Grey himself was initially upset at the commercialization of his work, but later forgave McCloud, including the image in published collections of his work and signing 500 of the blotter sheets.[19] McCloud's collection includes blotter art based on works by psychedelic artist Rick Griffin, including his Surfing Jesus, The Gospel of John, and the print Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory, which depicts Jesus and a Native American man smoking joints with the hookah-smoking caterpillar from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in the background. His collection also includes sheets of the comic strip character Snoopy from 1981, a full-color, perforated 44-tab piece from 1976 of a mouse and bunny with a birthday cupcake, a 1977 sheet with a Tetragrammaton with occult imagery, octopuses from Jules Verne, unicorns, and ants.[5]

Older pieces from McCloud's blotter art collection have been exposed to ultraviolet light to eliminate any residual LSD.[b] Nevertheless, McCloud was prosecuted by United States law enforcement agencies in 1992. He was acquitted but charged again in 2000, with conspiracy to manufacture and distribute LSD, following a year-long stakeout of his home. A raid found 30,000 sheets of undipped, perforated blotter art, which prosecutors argued McCloud was supplying to chemists and wholesalers.[4] After protracted legal battles, he was acquitted in both instances.[2] The legal cost for McCloud's defense in the 2000 case is estimated to have been over $500,000.[4] Some of the blotter art that was confiscated by the FBI now bears markings from the agency.[19] A binder of blotter sheets used as evidence by the prosecution in the case was obtained from drug busts throughout the United States in the decade prior to McCloud's arrest. It was later published by McCloud and Adam Stanhope as The Bust Book and included side-by-side comparisons to pieces from McCloud's collection. A special edition of the book included a sample of original blotter art depicting the Eye of Horus which is thought to be the oldest extant example of the medium.[4] Items from McCloud's collection can be viewed at his website Blotter Barn.[7]

Thomas Lyttle started collecting blotter art after meeting with McCloud. He produced vanity blotter art, limited edition runs of undipped blotter art prints that were then signed by luminaries in the psychedelic community such as Albert Hofmann, Timothy Leary, Ken Kesey, Laura Huxley, Alexander Shulgin, Robert Anton Wilson, and John Lilly. Sales of blotter art designed by Stevee Postman and signed by Hofmann were auctioned to raise funds for the drug information organization Erowid and for a study on the use of MDMA for treating post-traumatic stress disorder by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies.[21][4]

Blotter art has been exhibited at art galleries,[22] including Fort Lauderdale's Galerie Macabre, the Ever Gold Gallery[23] and FIFTY24SF in San Francisco,[24] Method in Mumbai,[25] the Fuse in New York City, and Miami's Luna Star Café.[4]

Markets for undipped blotter art exist on Etsy, eBay, Online Blotter Stores and the dark web.[26] Ken Kesey's son Zane has previously sold blotter art on the website key-z.com.[27] Contemporary blotter artists include Ziero Muko.[28]

Production and non-LSD blotter[edit]

Sheets of blotter art may be of various sizes but are often 7.5-inch (190 mm)-square and perforated into a 30 by 30 grid, resulting in 900 individual tabs measuring 1⁄4 inch (6.4 mm) on each side.[29] Early production of blotter acid involved hand-cranked machines to perforate the sheets, while contemporary perforation is often done professionally with automated die-cutting machines. Designs on blotter art may be stamped or printed, for example with a four-color-process.[4]

Blotter as a delivery method allows for easy dosing of potent substances and easy sublingual administration of drugs which has made it popular as a medium for other potent drugs. Other drugs active in the microgram range are also distributed on blotting paper and carry blotter art, including 25I-NBOH,[11] 25I-NBOMe, Xanax,[30] Bromo-DragonFLY, and DOI.[13]

See also[edit]

- History of lysergic acid diethylamide

- LSD art – Art inspired by psychedelic experiences

Notes[edit]

- ^ Dosages for blotter LSD often range from 75 to 100 µg, less than that of earlier incarnations, when a single dose was around 250 µg.[5]

- ^ LSD has a short half-life and loses its potency quickly. Preserved blotter art that once contained LSD typically contains no psychoactive ingredients due to the passage of time, ultraviolet light, or exposure to oxygen.[20]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Anthony, Gene (2004). Magic of the Sixties. Gibbs Smith. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-58685-378-5. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ a b c d e "LSD blotter art – How illegal drug distribution turned into art". Trancentral. 29 August 2016. Archived from the original on 19 June 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Federal Sentencing Guidelines and Drug Offenses: United States Supreme Court Decides Weight of LSD Includes Medium Used to Distribute Drug". The Army Lawyer. Judge Advocate General's School. August 1991. pp. 33–34. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lyttle, Thomas (Summer 2004). "LSD Blotter Art" (PDF). Maps. 14 (1): 35–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-16. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jarnow, Jesse (2016). Heads: A Biography of Psychedelic America. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-306-82256-8. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ a b Sfetcu, Nicolae (2014). Health & Drugs: Disease, Prescription & Medication. Nicolae Sfetcu. p. 1958. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ a b c d e f Rhodes, Margaret (19 February 2016). "Inside the LSD Museum That the DEA Somehow Hasn't Torn to the Ground". Wired. Archived from the original on 10 May 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ a b c Stix, Gary (2009). "The Start of Everything: LSD". Scientific American. 301 (3): 70–94, 96–98, 100. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0909-79a. ISSN 0036-8733. JSTOR 26001528. PMID 19708530. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ Downing, Henderson (2008). "More News From Nowhere". AA Files (57): 64. ISSN 0261-6823. JSTOR 29544695. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ James, Diaz (2006). Color Atlas of Human Poisoning and Envenoming. CRC Press. p. 471. ISBN 978-1-4200-0396-3. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ a b c "Warning over small paper square drug after Paisley seizure". East Lothian Courier. 24 June 2018. Archived from the original on 14 July 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Bergeron, Tiffany (23 August 2018). "Expanding consciousness". Boulder Weekly. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ a b Zevic, Mishor; Ward, Christopher J.; Leuenberger, Daniel (2015). Manual of Psychedelic Support (PDF). Psychedelic Care Publications. pp. 293, 301. ISBN 978-0-646-91889-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-05-25. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ a b Semley, John (1 November 2022). "Meet the California State Senator Who Wants to Decriminalize Psychedelics". The Nation. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Olive, M. Foster (2008). LSD. Infobase Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7910-9709-0. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ Haze, Xaviant (2017). Liquid Conspiracy 2. SCB Distributors. ISBN 978-1-939149-91-6. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ Salinger, Tobias (17 June 2015). "See It: Investigators find LSD tabs decorated with 'Breaking Bad' characters, release video of clandestine Miami drug lab". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ a b Oroc, James (2018). The New Psychedelic Revolution: The Genesis of the Visionary Age. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-62055-663-4. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ a b Sexton, Jason S. (1 December 2015). "Jesus on LSD". Boom. 5 (4): 78–84. doi:10.1525/boom.2015.5.4.78. Archived from the original on 11 February 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Chantry, Art (2015). Art Chantry Speaks: A Heretic's History of 20th Century Graphic Design. Feral House. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-62731-013-0. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ Crawford, Tiffany (22 April 2016). "B.C. scientists to auction off LSD images to raise money for PTSD study". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Roberts, Andy (2008). Albion Dreaming: A Popular History of LSD in Britain. London: Marshall Cavendish. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-905736-27-0.

- ^ Thomas, Gregory (12 November 2010). "LSD Museum or Institute of Illegal Images?". Mission Local. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Gaworecki, Mike (26 June 2015). "Far-Out New Show At FIFTY24SF Showcases Local Blotter Art Collection". Hoodline. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Kumar, Jaishree (19 April 2021). "This Psychedelic Art Pays Tribute to the First Ever Acid Trip". Vice. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Guthrie, Norie; Carlson, Scott (2018). Music Preservation and Archiving Today. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-5381-0295-4. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ LLC, SPIN Media (October 2011). The Merry Pranksters Get Off the Bus. SPIN Media LLC. p. 84. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ Teague, Marcus (6 March 2023). "Recap: Mona Foma Hobart 2023 – A Four-Day Mash-Up of Merkins, Music and Magical Voices". Broadsheet. Archived from the original on 18 March 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Grob, Charles S.; Grigsby, Jim (2022). Handbook of Medical Hallucinogens. Guilford Publications. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-4625-5189-7. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ "Intelligence Alert: Xanax Blotter Paper in Bartlesville, Oklahoma". Microgram Bulletin. U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. May 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-05-21.

Further reading[edit]

Media related to Lysergic acid diethylamide tabs and blotters at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lysergic acid diethylamide tabs and blotters at Wikimedia Commons- Davis, Erik (2023). Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-04850-7.

- Owen, Ted (1999). High Art: A history of the psychedelic poster. Sanctuary. ISBN 978-1-86074-256-9.