A good exhibition and a good catalogue always teach you something new about a painter you think you know. Laura Knight. A Panoramic View opened at the MK Gallery, Milton Keynes in October last year. I haven’t seen the exhibition yet but fortunately it has another month to run, so if you want to see why Dame Laura Knight (1877–1970) is one of the greatest British painters of the twentieth-century you must go.

If you can’t get to Milton Keynes, the lavishly-illustrated accompanying book, Laura Knight. A Panoramic View edited by Fay Blanchard and Anthony Spira (Philip Wilson Publishing 2020, 218pp.), is the best guide I’ve read to understanding her unique talent and artistic personality. Wonderfully, this catalogue gives a lot of space for Knight herself to speak. There is nothing better than hearing a painter explaining their work, particularly when the discussion is so insightfully chaired by the editors. The introduction setting the show’s programme is worth quoting, and at length.

In Knight’s words, ‘Even today, a female artist is considered more or less a freak.’ She was writing in 1965, the year of her solo exhibition at the Royal Academy – the first ever for a woman…. Laura Knight (1877–1970) was unquestionably one of the most popular and pioneering British artists of the twentieth century. Her artistic career took her from Cornwall to Baltimore, and from the circus to the Nuremberg Trials. She painted dancers at the Ballets Russes and Gypsies at Epsom races, and was acclaimed for her work as an official war artist. Hers was a career of firsts: the first woman to be elected to full membership of the Royal Academy, the first female artist to be made a Dame of the British Empire, the first woman to be invited to select for the Venice Biennale – the list goes on.’

This cannonade of a resume reveals a forthright personality, which perhaps explains why so many of Knight’s best female portraits seem also to contain something of herself. The best known, the portrait of the outstanding armaments worker Ruby Loftus screwing a Breech-ring 1943 was the result of a day’s observation in an armaments factory. It captures the precision and concentration needed to make a crucial component for a Bofors anti-aircraft gun, in which the slightest error could cause a fatal misfire. For a private wartime commission Knight also spent time at Skefko’s Ball-Racer factory. Knight Described how she was showered with oil and sparks, until her shoes ‘rotted away on the oil-laden floor… I learnt from the foreman on my first morning that the betting in the shop was that I wouldn’t last out even for one day. Perhaps that was what made me “last out” six weeks.’ Knight’s portraits of three winners of the Military Medal in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force portray a similar steely determination and devotion to duty.

Assistant Section Leader Elspeth Henderson MM and Sergeant Helen Turner MM, Women’s Auxiliary Air Corps 1941, Imperial War Museum, London

Assistant Section Leader Henderson (1913 – 2006) and Sergeant Turner were both on duty when their building at RAF Andover took a direct hit. They continued working until the building caught fire and they were ordered to leave.

Corporal Robbins was sheltering in a dug-out during an air raid on RAF Biggin. When the dug-out took a direct hit killing two men and severely wounding two more she remained behind to help them as the dugout filled with fire and smoke, displaying – in the words of the medal citation – ‘courage and coolness of a very high order in a position of extreme danger.’

The catalogue takes Knight from her earliest work as a Newlyn School painter before and during the First World War, through to her delighted in subjects showing physical exercise. She produced studies of ballet dancers and boxers in the 1920s and 30s and in 1923 she became vice president of the United Amateur Wrestling and Weight Training Club in London.

Far less well known – to me at least – was the intense work that Knight put into developing a style for her documentary paintings, taking something of the emotional intensity of Stanley Spencer and keen to avoid the pageantry of Frank Salisbury. Knight believed that an artist should always surprise their critics and continually develop and experiment with their style. Her expressionistic landscapes were entirely new to me.

In a letter from 1959, Knight describes the process behind Storm over Our Town, Malvern:

‘This picture took me years to paint. What happens in that fraction of an instant in time when lightning strikes? I had to see it time after time to memorize how the brilliance of the stroke lights, even brighter than the light of day, whatever object it comes near. Just the zig-zag usually painted that illuminates nothing is not the truth. What a complication of study – not seen every day. “Our Town” is Malvern; the Church is Malvern Priory. A storm was taking place one day when Harold rushed to me downstairs at the Mount Pleasant Hotel where we were staying: “Come up to your bedroom quick and see what’s going on, it’s wonderful.”‘ The catalogue notes this dynamic painting’s debt to El Greco’s View of Toledo 1595 – 1600 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) which Knight had seen in New York in 1922.

Knight described her unpopulated post-war landscapes such as Sundown, another visionary Malvern landscape, as a ‘visual indulgence’. She captures exactly the light when ‘at sundown, looking westward, behind the tumble of little hills we watched together the extravagant glory of the sun sinking to rest in the empurpled sheets of cloud.’

The catalogue is divided by thematic essays arranged in chronological order: The Heat of the Bodies by Lubaina Himid and The Interwar Years by Sophie Hatchwell cover the first half of Knight’s career. Pictures within Pictures by Hannah Starkey and Between Painting and Performance by Monster Chetwynd deals in detail with Knight’s fascination with the ballet and the circus. The article by Damien Le Bas The sky for a ceiling describes Knight’s love of gypsies and the gypsy life, taking its title from Knight’s own words ‘the sky is their ceiling’. But in A Complicated Artist Barbara Walker does not shy away from a problematic aspect of Knight’s character. In 1927 Knight painted a series of portraits of Black sitters in Baltimore. These portraits were considered revolutionary enough that when they were later exhibited in London a front page article for the Daily Herald said that ‘it is even conceivable that her boldly sympathetic attitude… may cause a considerable stir.’

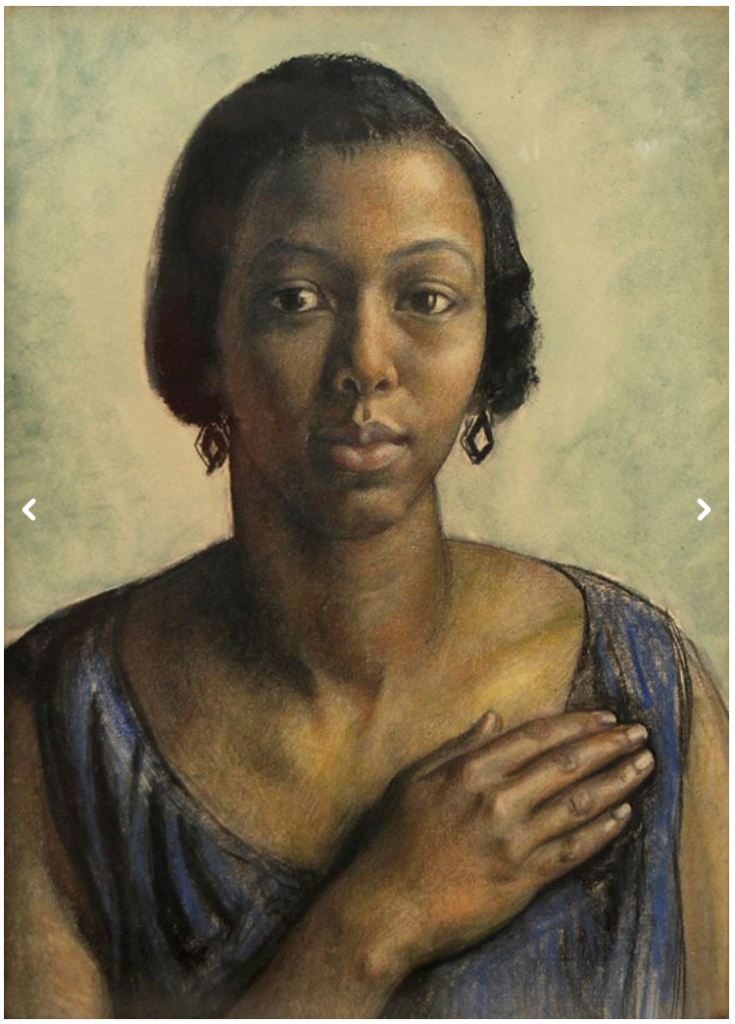

The watercolour and pastel portrait of Pearl Zelma Johnson (c.1896 – 1997), a nurse at John Hopkins Memorial Hospital, was a study for a double portrait with her sister Irene Johnson Dodson (c.1899 –1994) who worked as an office manager at the hospital, against a background of Baltimore skyscrapers. The catalogue says that the sisters were Members of the Interracial Fellowship Group campaigning against segregation in Maryland: ‘They took Knight to a ‘social’ at which there was a lecture on civil rights, and also to a concert and exhibition.’ Knight was a social progressive. She was a feminist, and a humanitarian who protested the persecution of German Jews before the Second World War and would consider her painting of The Nuremberg Trials to be perhaps her greatest work. She admired and identified with gypsies, and yet as Walker reveals, in her writing she referred to Black sitters in terms which were not intended to be insulting but would not be used today. Walker notes this disconnection, between Knight’s instinctive sympathy with marginalised groups, the revolutionary (because respectful) treatment of the sitters, and the language she uses. But she does not try to explain or excuse it, noting ‘To be sure, Knight was a complicated artist who has left an unresolved legacy.’ This is a wise response to this sort of question.

My only criticism of the book, and it is a very slight criticism, is that the image captions give all details except the work’s location and I do like to see at a glance where a painting is without having to turn to the image credits at the back of a book.