Some day, I'd like to write a comic. It doesn't have to be superhero, though that would be great, it just has to be something with pictures to go with my words, told sequentially, and have dialogue trapped in little bubbles with a funnel pointing at the principal's head. In order to make this pipe dream a little less pipey, I need a wealth of knowledge of the medium. So I decide to make my way through the classics and the acclaimed: Gaiman, Moore, Tomine, Eisner, Hernandez, Satrapi, Spiegelman, Morrison -- There's a lot of them.

Recently, I decided to pick up Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Boy on Earth by Chris Ware. You've probably seen it around in stores. It's that odd, long, rectangular book in the graphic novel section with the flat, basic shape art. It exudes differentness, that is, you can tell it's arty and difficult because it doesn't give a shit about fitting nicely on your bookshelf. What follows is my amateur thoughts and ideas, having now finished the thing.

My first exposure to Ware was a curious cover/comic he did for an edition of Voltaire's Candide for Penguin Classics. It was weird and even out of place, but that just made it seem like a daring choice. That's the basic vibe I get from this book too: an overall strangeness that is a little difficult read, but the investment brings you in closer overall.

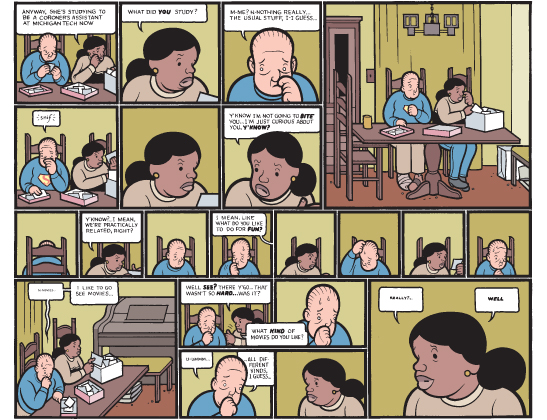

Traditionally in comics, the idea is to create a flow for reader's eye to travel the narrative, panel by panel. You easily communicate ideas through concise images and the best artists uniquely but coherently lead you along with subtle composition and illustration choices. Chris Ware throws that idea out, meaning: this book is a pain to read. This book doesn't care about holding your hand and creating a logical reading experience. It wants you to work for it. Other classics carry you on a bed of velvet pillows to the end. Jimmy Corrigan waits for you to come to it, because it doesn't need you, it's fine staying right where it is -- but in many ways that makes you want to get into it more.

The first thing is the size of the art. The panels get stamp-sized or smaller, with words that never get much bigger. Everything is arranged to a grid, sometimes with subgrids within the grid. This makes for beautiful Mondrian-like composition when viewed as a page, but as a traveller through the story, you're at a loss of where to go next. Sometimes Ware throws you a bone with a directional arrow, but they are few and far between. You're navigating tiny panels that start to feel like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, trying to arrange them logically in places that should fit.

The result is that you are studying every page, and it is completely engrossing. You are forced into tunnel vision so that you may examine panels, read slowly, appreciate the simplistic art and colors. It absolutely breaks the laws of comic pacing in this way, making the whole story slower and methodical, but in a book that is mostly about loneliness and tragedy, it fits. There are no huge action sequences or even a lot of actions. Just an old man, his strange mind, and his father.

The subtitle, "Smartest Boy On Earth," really isn't what the story is about. In fact, Jimmy's not all that smart. In fact, he's rather lonely and awkward and pitiable. "Smartest Boy on Earth," is a fantasy childhood of adventures featured in older, non-included Jimmy Corrigan comic strips. This older Jimmy is a sad guy that contrasts to the high-energy cover and whimsical title. He's sad, lonely, old man with an active imagination and all the flaws and insecurities in the world. He indulges in the privacy of his mind, he panics at the threat of disapproval, and he tries to get through his day with the demeanor of a frightened child.

Things reach a new level for Jimmy when he mysteriously gets a letter from his estranged father, asking for a reunion. Against the wishes of his overbearing mother, it's secretly off to meet his father, not knowing why, not knowing what to expect. A good chunk of the book is dedicated to the even more depressing childhood of Jimmy's grandfather, taking place at the turn of the century, living in a men's group home, a victim of abuse, in the shadow of the Columbia Exposition during a transitional moment for Chicago. The interesting piece of history throws you for a loop for a little, where some beautiful prose is thrown in the tiny panels, but this parallel story has some of the most delicate and moving moments of the whole novel.

That's what the whole story is: Moving. It starts with Jimmy and eventually turns into being about the whole Corrigan line, and the seemingly hereditary loneliness. The New Yorker called it, "The first formal masterpiece of the medium," and they may be right. Alternative, indie and the general non-cape comics tend to fall into this same sort of emotional/lonely/surreal cartooning trope, but it's hard to think of it done in a way that is more artful and meaningful than Chris Ware's work. A lot of people may attempt to do what he's done with Jimmy Corrigan, but it's the standard-setter for a reason.