ArtSeen

Monica Sjöö: The time is NOW and it is overdue!

On View

Beaconsfield GalleryThe time is NOW and it is overdue!

June 11–September 10 2022

London

When Monica Sjöö’s canvas God Giving Birth (1968) was installed at St. Ives Town Hall in 1970 it was met with immediate controversy. The challenge to Christian conceptions of God posed by its depiction of a woman of color delivering a child outraged the town mayor, who demanded its removal on grounds of blasphemy. When it was displayed again three years later at an all-women group show in London, the artist narrowly avoided obscenity charges brought by religious fundamentalists. Now held in the collection of Museum Anna Nordlander—a women’s art museum in Skellefteå, Sweden—God Giving Birth is regarded today as the Swedish radical’s most iconic work, and as an emblem of second-wave feminism.

Notwithstanding the importance of the image within British social history, Sjöö’s other paintings are rarely exhibited, even fifty years later. She is primarily remembered for her revolutionary writings and manifestos, such as The Great Cosmic Mother (1987), which she co-authored with Barbara Mor, a staple of women’s studies syllabi. But her paintings are subject to renewed interest thanks to a show of more than fifty of her works, many of which have remained unseen until now, at Beaconsfield Gallery in London. Aligning with her inclusion in Tate Liverpool’s Radical Landscapes exhibition and a small presentation of her work at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, the Beaconsfield display offers a much overdue opportunity to revisit the artist’s visual practice through the lens of the climate crisis.

Sjöö’s language and approach are more relevant than ever. Born in Sweden but a resident of the United Kingdom for most of her life, she was an ardent anarcho-environmentalist whose radicality could always be measured by the analogous outcry she received from the white male art world. Despite Sjöö’s status as a pioneer of eco-feminism and one of the first proponents of the Goddess movement—a matriarchal strain of paganism that emerged in the 1970s—she is far less a household name than her friends and contemporaries such as Judy Chicago and Lucy Lippard. Perhaps that is partly due to our inability to classify her politics as neatly as historiography would like us to. Her convictions spanned many of the radical leftist platforms that underpinned the counterculture movement: anarchism, feminism, environmentalism, pacifism, and anti-racism. Other beliefs she held sometimes appeared contradictory, even if they were not. She espoused that heterosexuality was unnatural and enforced by patriarchal culture but occasionally had relationships with men; she practiced Earth spirituality and esotericism but was unwaveringly critical of New Age religions.

This rejection of a single identity, however, is what makes her work resonate so compellingly now. Keenly aware that humanity’s brazen domination over the earth is inextricably linked to all forms of hegemony, Sjöö supported the liberation of all subjugated peoples. Executed in 1968, a year which saw the artist spend time in New York, After Oppression Revolution highlights the activism of women of color during the apex of the civil rights and Black Power movements. Several other works, including Housewives (1973) and Women’s Work and Crafts (1975), portray the backbreaking labor carried out by women that is all too often disparaged as simple or trivial. Furthermore, in Our Bodies Our Selves (1974), two women’s uncovered breasts press together in a tender kiss—an embrace that is an unapologetic challenge to heteronormativity and a celebration of lesbian erotics, a tribute to love liberated from all notions of hierarchy.

The directness of Sjöö’s imagery can be striking, such as in Birth and Struggle for Liberation (1970), which depicts a woman, encircled by the sun, rather graphically giving birth. “WE REJECT… the ‘art for art’s sake’ philosophy of the privileged white middle-class male artworld… [Our task is to convey] God-Woman giving birth to the universe out of her bloody womb, life, death, rebirth…” she and Anne Berg declared in their “Images on Womanpower – Art Manifesto” from 1971. Like her writings, her paintings don’t mince words. They echo one of her most resounding proclamations, from which the exhibition takes its title: “The time is NOW and it is overdue!”

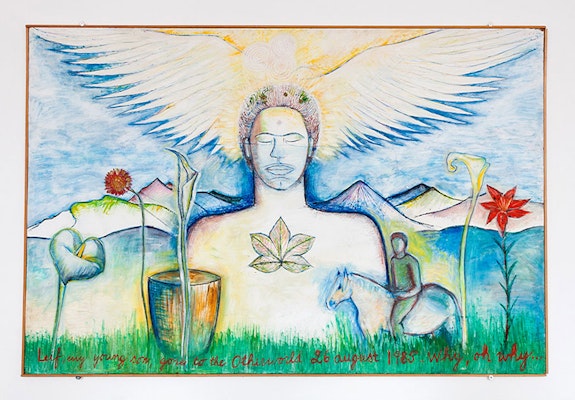

A later example from her career, Mother Earth in pain, Her trees cut down, Her seas polluted (1996), is a brutally evocative image that likens ecological destruction to physical violence and acts as the vivid anchor of the exhibition. A female personification of the natural world weeps in pain, the visual hinge uniting an oil spill with the bloody stubs of a forest, gorily rendered like cut-off limbs. Many of the works on view are from the 1990s, a period of especially ardent spiritual introspection for Sjöö following the tragic deaths of two of her sons. Coinciding with the rampant rise of neoliberal politics that had kicked off the previous decade, as well as further environmental destruction at the hands of the global north, this time was spent by the artist exploring more ethical modes of being, put forth by matriarchal cultures. Spanning ancient Africa, pre-modern Europe, and the Americas, the iconography of goddesses is abundant in her later work, which is replete with allusions to spirit masks, Our Lady of Guadalupe, and Celtic mythology.

Sjöö’s interest in this imagery deserves a more nuanced discussion than the logistical and thematic limitations of the Beaconsfield show (as a preliminary reintroduction of her work) or this review could ever allow. Though her employment of these forms might appear startlingly appropriative at first glance, they are the result of a deep study of—and an earnest and profound respect for—belief systems that she perceived as rejecting Western modernity, control, and greed. She often defended their intricacy and sacredness, joining arms with activists of color to rebuke New Age religions for what she considered to be a blatant simplification and exploitation of Indigenous culture. In this sense, her use of these images is less an aestheticization of the “primitive” à la Cubism than a desperate search for answers generated by an existential fear of global collapse. Given her understanding of patriarchy as the primary source of hegemony and ecological destruction, she viewed her engagement with these women as not only consensual but imperative in order to visualize a viable alternative world-system. However, the politics of any transnational exchange between two very unequal states is always fraught with complexity, and contemporary feminist and race discourse might illuminate new perspectives on this chapter of her work.

As our increasingly precarious existence is threatened by patriarchal treatments of the environment and society, where do we look to find a way forward? Seeing her paintings now, a few propositions begin to emerge. What if we reimagined humans as symbiotic participants within a planetary ecology as opposed to masters entitled to dictate, control, destroy, and consume what we wish? Could this principle, instead of hegemonic individualism, become the thread that weaves together our society? And what if, to conceptualize this way of life and exist correspondingly, we followed the lead of Indigenous voices, who have led sustainable land stewardship for millennia? The fact that the future of the planet shows no more promise than it did fifty years ago, that the arc of the moral universe might in fact not bend towards justice, is certainly dispiriting. But Sjöö’s paintings are more than just a reminder of that. They provide hope that if the art of the past mirrors contemporary issues, it might provide solutions, too.