JournalofHigherEducationManagement

Volume 37, Number 2 (2022)

1

AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY ADMINISTRATORS

JOURNAL OF HIGHER EDUCATION MANAGEMENT

Volume 37, Number 2 (2022) ▪ ISSN 2640-7515

Dan L. King, Editor

Direct all correspondence to: Dan L. King, President and Chief Executive Officer, American Association of University Administrators. Postal Address: 1 Ralph Marsh Drive, Glen Mills, Pennsylvania 19342 – USA. Phone contact: 814-4606498. Email: dking@aaua.org.

Governance of the Journal of Higher Education Management is vested with the Publications Committee of the Board of Directors of the American Association of University Administrators. Committee membership includes:

Sr. Ann Heath, IHM, Chairperson

Kathleen Ciez-Volz Immaculata University Florida State College at Jacksonville

Jeffrey B. Leak

James M. Owston University of North Carolina at Charlotte Alderson Broaddus University

Neil Trotta

Julie E. Wollman Fisher College University of Pennsylvania

Opinions expressed in articles published in the Journal of Higher Education Management are those of the individual authors, and should not be taken as being representative of the opinions or positions of either the Journal, or the American Association of University Administrators, or of sponsors of this publication.

© Copyright 2022 by the American Association of University Administrators. Permission to reprint for academic/scholarly purposes is unrestricted provided the citation and permission statement appears on all duplicated copies. All other rights are reserved.

2

CONTENTS

Creating Sustainable University Structures for Offices of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) (Nwando Achebe, Carole Gibbs, Brian Johnson, Daniel Valez Ortiz & Chioma Nwaiche) 22

4

Hearing Diverse Perspectives: Authentic Signaling in Faculty Recruitment (Brent S. Opall, Kranti Dugar, Kevin Hansen, Nancy Hanson-Rasmussen & Bridget Kurtenbach) 39

Allyship Accountability in Academic Leadership: The Power and Responsibility in Privileged Roles (Jacob Bucher) 49

Looking for the Dream School: Understanding the Lived Experience of the College Choice Process (Ryan Ladner) 68 Do Academic Supervisors Know What Their Employees Want From Work? (John Griffith & Emily Faulconer) 80 Faculty Perceptions of the Essential Elements of Leadership Across Generations and Sex (Seth Kastle, Haley Moon & Jeni McRay) 97 Transferability to a Four-Year Institution: A Focus on an Urban Community College’s School of Business (Dan Hornick, George Hummer & Jeffrey L. Wilson) 103 A Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding College Students’ Experiences Throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic (Sarah Y. T. Hartzell, Megan E. LaMotte, Molly Hagen & Paul Devereux) 128

Resource Allocation Concerns: Matching Teaching and Research Needs with Financial Management at University Farms (Justin W. Rickard & Maria A. Boerngen) 136 The Nexus Between Corporate Governance and Leadership in the Post COVID-19 Era: The Context of Public Sector (Oluwassun Titi Adeosun) 148 Directions for Contributors 149 A.A.U.A. Board of Directors

3

, 37(2), 4-21 (ISSN 2640-7515).

All other rights reserved.

Creating Sustainable University Structures for Offices of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

Nwando Achebe1 Carole Gibbs Brian Johnson Daniel Velez Ortiz Chioma Nwaiche Michigan State University

Introduction

Giving voice to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) perspectives can be a risky endeavor for DEI Champions in higher education, but also for DEI administrators who are part of institutional governance, but are not given the power, authority, and resources to do their work. These voices are often suppressed because DEI does not have a legitimized position within administration. It is with an understanding of this reality that we, as a DEI Administrator and Fellows, approach the work that we have done and continue to do. It is in this same spirit that we offer this assessment of our lived experience in engaging in DEI work at our university. We seek to advance DEI, while holding space for harm reduction and accountability.

The story of our work begins in 2020, when the dean of the College of Social Science (SSC) at Michigan State University (MSU) left the university for a higher position as Provost. Before she left, she announced the creation of a new Associate Dean for DEI. The position announced, however, was conceptualized as an afterthought and add on, instead of integrated into the overall administration structure. Moreover, the roles and responsibilities of the new position were limited —the focus was entirely on faculty. The new Associate Dean was not allowed to work with staff or students, nor did she have the authority or resources to do the work that needed to be done. An interim dean was soon named and was hesitant to extend the duties of the new Associate Dean to be inclusive of all DEI goals. After much dialogue with the Associate Dean, the interim dean encouraged her to put into writing her vision of the office for Associate Dean and how that position would align with other Associate Dean positions, and the Dean’s Office in general. The proposal would correct the existing problematic structure in the Dean’s Office. This was the impetus for the developing and writing of the SSC DEI office proposal; and the work was undertaken by members of the new Dean’s DEI Fellows in collaboration with the Associate Dean. In the absence of human and monetary resources, and broad support for the DEI mission of the College, the Dean’s DEI Fellows Pilot Program had been established. The Fellows, faculty from across the SSC and a graduate student, support the Associate Dean’s DEI efforts while building leadership skills in the DEI arena.

1 In light of our radical and transformative approach to DEI, we note that all authors contributed equally to this manuscript. To accommodate requirements for order of authorship, we alternate who serves as first author and list ourselves alphabetically thereafter.

4

Journal of Higher Education Management

© Copyright 2022 by the American Association of University Administrators. Permission to reprint for academic/scholarly purposes is unrestricted provided this statement appears on all duplicated copies.

The Dean’s DEI Fellows and Associate Dean undertook this charge with a singleness of purpose. Regardless of whether the interim dean or the new dean agreed to put into place the recommendations from the proposal, the Dean’s DEI Fellows and Associate Dean felt strongly about the proposal because how university DEI efforts are structured is important. The proposal aligned with best DEI practices and was evidence based. Thus, it represented a blueprint for DEI organizational structures at institutions of higher education. Furthermore, producing this DEI Office Structure document was important as it could not only codify DEI in SSC, but also serve to create DEI memory, sustainability, and continuity between administrations.

Codifying and creating sustainable DEI requires structure and process (Thomas, 2021; Harris, 2021; Ahmed, 2012). John Paul Kotter, thought leader in business, leadership, and organizational change, introduced an 8-stage organizational change framework in a 1995 article entitled “Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail.” This process-based framework has been applied to numerous organizations over the past 20 years, and updated in Kotter’s (2014) book to reflect lessons learned. The 2014 framework includes the following steps: (1) Create a sense of urgency; (2) Build a guiding coalition; (3) Form a strategic vision and initiatives; (4) Enlist a volunteer army; (5) Enable action by removing barriers; (6) Generate short-term wins; (7) Sustain acceleration; and (8) Institute change.

In the current paper, we situated our experiences and efforts to design and establish the proposed DEI office within Kotter’s (2014) organizational change framework. Such an office would institutionalize the college’s efforts to advance DEI. We selected Kotter’s framework because it contains practical steps for, and stages of, organizational change. Although Kotter situates his processes within the business sector, his organizational change framework has been used to study and assess change efforts (e.g., CDO implementation of diversity plans) in higher education (e.g., Stanley et al., 2018).2 We found it to be a useful model for shaping our change effort, but found that the stages articulated often overlap in the real world. In some instances, our DEI work connected to multiple steps. We found this to be true as we navigated the contours of creating our DEI structures document and doing DEI work in SSC.

Background

John Paul Kotter identifies “creat[ing] a sense of urgency as the first stage of organizational change. He visions it as an exigency to “help others see the need for change through a bold, aspirational opportunity statement that communicates the importance of acting immediately” (Kotterinc.com, n.d.). In the University context, this urgency for change can emerge from a broader context of racial unrest, heightened awareness of existing disparities in faculty representation, gaps in student success across racial lines, and sexual misconduct, spurring universities to articulate an “aspirational opportunity statement” to act. Indeed, it is against this backdrop that University efforts to institutionalize DEI have often occurred with a heightened sense of urgency to act. Urgency created out of obligation is performative, and rarely sustained.

2 Some have noted the challenges of using Kotter’s framework to change outcomes or processes controlled by faculty (e.g., curriculum), as faculty have much more autonomy than employees in a corporate setting (Kang, et al., 2020). However, faculty are not the focus of our change effort.

5

In fact, higher education has been under increased scrutiny for failure to address inequalities in representation and educational opportunities and outcomes. Regardless of high-school test scores, Black and Hispanic students are less likely to earn a college degree within 10 years in comparison to White and Asian students. Similarly, bachelors’ degree attainment is much lower among firstgeneration, low-income students, and far more likely among students from families in the highest income quartile. Blacks, Hispanics and Native Americans are also underrepresented in the conferral of all advanced degrees, particularly Masters’ and Doctoral degrees, in comparison to Caucasians (Carnevale, Fasules, Quinn and Peltier Campbell, 2019: 25). Critics charge that many universities fail to implement changes that can help reduce such gaps, such as inclusive pedagogy (Gooblar, 2020) and supporting students through graduation, not just recruitment (Holzer and Baum, 2017; Fischer, 2019). Representation in minoritized faculty is also dismal. As of 2019, Whites were overrepresented in tenure-track faculty positions in comparison to the U.S. population and the U.S. undergraduate student population, while African-American, Hispanic and Native American faculty remain underrepresented (Matias, Lewis, Jr. & Hope, 2021). Taken together, these disparities have galvanized an “immediacy of action” in academic leadership to inspire their communities to see the need to together find solutions to these issues.

MSU is no different in its challenges. The university has reported disparities in six-year graduation rates by race and between Pell and non-Pell students and first generation and non-first-generation students. In addition to being less likely to graduate in six years, Black and Latinx students are less likely to persist after their first semester and more likely to be placed on academic probation than White and Asian students (Largent, 2019). These gaps spurred urgency in MSU’s SSC to create a guiding coalition of stakeholders (faculty, staff, students, alumni) who collaboratively produced a college-wide strategic plan which articulated the need for change and improvement in persistence rates. The College committed to achieving a 5% improvement in six-year graduation rates and a 50% reduction in opportunity gaps for underrepresented minoritized undergraduates (SSC Office of the Dean, n.d.). This commitment represents “a volunteer army,” in the SSC context. The strategic planning committee, comprising a "coalition of effective people – born of its own ranks” was engaged “to guide . . . coordinate . . . and communicate [these change] activities” (Kotterinc.com, n.d.). As with other universities, African American, American Indian and Hispanic faculty are underrepresented at MSU among tenure-stream faculty (MSU Office of Inclusion and Intercultural Initiatives, 2020). This urgent need was addressed in the College’s Strategic plan, by its guiding coalition of stakeholders. One of the main foci of the DEI section of the plan was to grow the number of minoritized faculty and future faculty.

In addition to concerns regarding faculty representation and opportunity gaps, MSU experienced a major sexual abuse scandal and series of racist incidents on campus over several years, all creating additional pressure and urgency for the advancement of DEI. Faculty member Larry Nassar serially sexually abused more than 160 women and girls over several decades (Evans, Alesia & Kwiatkowski, 2018; Correa & Louttit, 2018). This resulted in the resignation, charging, and conviction of several high-ranking MSU administrators (Hauser & Zraick, 2018). In the wake of this negative publicity, the university president convened a “guiding coalition of stakeholders” to produce an institution wide “Relationship Violence and Sexual Misconduct Plan” to help foster a “safer campus community” (Office of the President, n.d.).

6

Unsurprisingly, the mishandling of sexual misconduct was not the university’s only failing. In 2019, several incidents targeted racialized groups on campus, including a toilet paper noose (Walker, 2019) and the destruction of property at the MSU Hillel Jewish Student Center (Tidwell, 2019). In addition, a faculty member studying how people respond to racist online speech sent a survey to students that failed to provide adequate warning regarding its offensive and profane content (Johnson, 2019). Continuing in 2020, staff at the gift shop at the Wharton Center for Performing Arts created a display of figures of African American leaders hanging from a rack resembling a tree (Das, 2020). Later the same year, students posted racist remarks in response to questions posed by Black students at a campus event designed for such questions, called “Ask President Stanley” (Guzman, 2020). Thus, one can argue that the congruence of these institutional failings and national events that made racial health inequities and police violence visible, spurred the need for urgent attention to DEI at MSU.

The newly appointed President Samuel Stanley and Provost Teresa Woodruff thus convened a guiding coalition to search for MSU’s first Vice President and Chief Diversity Officer. President Stanley also set up other coalitions—a DEI Steering Committee and Taskforce on Racial Equity—to guide, coordinate and communicate DEI change at MSU. The former inventoried existing efforts, gathered feedback, and reviewed best practices and metrics to measure progress (campus and unit specific) in order to devise a set of recommendations for advancement (Office of the President, n.d.). The latter created a series of recommendations to advance racial equity in the areas of policing, campus climate and safety, and faculty and staff diversity (Office of President b, n.d.).

Progress, however, has been uneven across campus. For example, as described further below, the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources is the only college on campus with an internally supported DEI office. In addition, there is a general disconnect between DEI initiatives around campus. Each unit and initiative were created independently, and only later were mechanisms generated to interface to some degree (MSU Office of Inclusion and Intercultural Initiatives, n.d.). Prior to a recent collaboration among three Associate Deans for DEI to create a Council of Diversity Deans (CODD), the DEI Deans were not connected across campus. The university’s Institutional Diversity, Excellence, and Action (IDEA) Coordinators—one in each college—arose in the 1990s as a network of individuals with DEI responsibility in MSU colleges and units. They meet as a committee regularly to not only support college and unit level goals related to DEI, but also to influence the direction of DEI in those units and serve as a resource for DEI work at MSU. The university’s Faculty Excellence Advocates (FEAs), who are selected by the Deans of each college to work as the drivers of DEI in all academic human resources in their colleges, meet as a consortium, separate from the IDEA coordinators or the Diversity Associate Deans. Michigan State University also has an Office of Intercultural Initiatives and Inclusion (OI3). Housed in OI3 is the Diversity Research Network (DRN), which provides a mechanism to help faculty of color and diversity scholars connect across campus to increase research collaboration and visibility. These entities, individual though they may be, in other ways can be viewed as guiding coalitions for DEI action across campus.

SSC context

With 291 tenure stream faculty, the SSC is the largest of MSU’S 17 degree-granting college (Office of Planning and Budget, 2021). The structure of the Dean’s Office includes a .51 full time-equivalent

7

(FTE) Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs who manages all matters relating to the hiring, reappointment, promotion, and tenure of SSC faculty. There is also a .75 FTE Associate Dean for Academic and Student Affairs who oversees all matters related to undergraduate students and studies. Then there is a .75 FTE Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Research. She oversees the grant research concerns of faculty and manages graduate studies in the college. The Dean’s Office also has a Chief of Staff and Business Operations Manager, Communications and Marketing Director, and Senior Development Officer. Completing the leadership team of the Dean’s Office, prior to recent changes, is a .25 FTE Faculty Excellence Advocate (FEA) whose job it is to work “with faculty, department chairs, and the Dean’s Office, to create a climate of, and meet its goals for, quality, inclusiveness, alignment, objectivity, consistency, and transparency of all academic human resource policies and practices (particularly faculty recruitment, retention, and advancement) in the College of Social Science.” (MSU Worklife Office, 2020).

In 2017, the SSC welcomed a new Dean. One of this new leader’s first charges was to lead the College through the Strategic Planning process. The Strategic Planning process, through a guiding coalition, identified DEI as one of 4 areas of focus for the college (College of Social Science, 2017). In the absence of institutional structure or resources, the DEI portion of the plan called for the creation of an ad hoc committee, the Dean’s Advisory Board on Diversity and Inclusion or DABDI, composed of students, faculty, and staff from the SSC. This board, a guiding coalition and volunteer army, served as an advisory council on all diversity matters to the Dean, but at the same time supported the FEA, who was able to enlist this army of numerous senior DEI allies and thinkers in her quest to drive large-scale change in the DEI goals of the college (College of Social Science, Diversity Matters a, n.d.). As an advisory board, it was DABDI that first “rallied around a common opportunity” to recommended to the Dean that the position of Associate Dean for DEI be reintroduced, as the position was not filled after a previous Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Diversity left the university. They applied pressure on the Dean by penning a memorandum to this effect. The Dean would eventually acquiesce and announce a university wide search for this Associate Dean position a few months before she left the university.

The DEI portion of the College strategic plan identified three areas of concentration: inclusive climate, faculty hiring and retention, and developing future faculty as focus areas. As part of the faculty hiring and retention, and developing future faculty foci areas, the Faculty Excellence Advocate led the creation of two new diversity hiring programs—the Dean’s Research Associate Program (College of Social Science, Diversity Matters b, n.d.) and the Dean’s Distinguished Senior Scholars Program (College of Social Science, Diversity Matters c, n.d.). Both programs promote an inclusive scholarly environment in which “outstanding scholars in the social sciences support the advancement of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the academy” (College of Social Science, Diversity Matters b, n.d.).

The fall 2020 hire of an Associate Dean for DEI represented the college’s first steps in attempting to institutionalize DEI in the college. The position, however, was not conceptualized with an understanding that DEI permeates everything that is done in a college or university. Instead, it was conceptualized as a stand-alone position, with little or no influence or far-reaching responsibility. Moreover, the position was constructed as a .51 FTE position, which included the responsibilities of the aforementioned FEA position, which was originally capped at .40 FTE. Thus, on paper the DEI

8

Associate Dean position only amounted to .11 FTE effort. Nonetheless, the new Associate Dean for DEI worked to form a strategic vision and initiatives, in order to “clarify how the future will be different from the past and how you can make that future a reality through initiatives linked directly to the vision” (Kotterinc.com, n.d.). In response to the requests from the interim Dean, the Associate Dean for DEI 1) developed a strategic vision for DEI in the SSC document that described the responsibilities and programs needed to institutionalize DEI across all domains (e.g., curriculum, recruitment, leadership) and 2) with the Dean’s DEI Fellows, created an office structure document to implement this work.

University-wide context

This conceptualization of the SSC Associate Dean for DEI position, however, does not necessarily reflect best practices in the DEI space, even at MSU. The same position in other colleges demonstrates this point. Although other colleges with more DEI infrastructure (e.g., Human Medicine and Veterinary Medicine) have supported such efforts by securing external grants, the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources (CANR) has a full-time Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion who manages an Office of Diversity and has full-time staff. While the SSC is the largest and most diverse college in the university, it lags behind on legitimizing DEI as a structural component of its administration. This contrast presents an example of how lacking a DEI structure leaves an uneven distribution of resources in the hands and charity of individual leaders. In the same way, this charity approach undermines the efforts to even create a sense of urgency for change.

Challenges to Institutionalizing a DEI Structure

In addition to determining how to best implement and sustain a college-wide DEI structure, further logistical challenges also had to be considered. One initial logistical challenge included who would govern ideas around the proposed DEI structure. Ideally, faculty, staff, and students would not only benefit from our DEI efforts but would also play a pivotal role in determining the structure and reporting systems of our proposed plan. One way that we addressed this goal was through utilizing the expertise of DABDI. With their support, we produced the Dean’s requested "Office of the Associate Dean of DEI” document and presented this proposal to her. This strategy represents an application of the "Build a guiding coalition” stage in the organizational change framework.

A second logistical challenge to implementing a college-wide DEI structure consisted of securing resources for sustaining it. The “generate short-term wins” stage in the organizational framework implies the need to have measurable achievements. According to Kotter, this process “must be recognized, collected and communicated – early and often – to track progress and energize volunteers to persist” (Kotterinc.com, n.d.). We achieved this while addressing this second logistical challenge. First, the Dean’s DEI Fellows Pilot Program was created to provide some support for the Associate Dean. It attracts SSC faculty to build leadership skills around DEI and prepares the fellows to lead internally and externally. These DEI Fellows come from various social science departments in the college and meet on a weekly basis to provide input, representation, and assistance in the SSC. Through this process, we embodied the “Form a strategic vision and initiatives” stage in Kotter’s framework, and also further contributed to the “volunteer army.” While working within a

9

decentralized administrative structure, the Associate Dean also encouraged every unit in the College to have a DEI committee. As a result, all units in SSC now have a DEI committee, another "short term win.” In addition, some forward-looking departments actually created administrative positions of DEI Coordinators. These DEI Coordinators were administrators on the same footing as Associate Chairs and Directors, and the creation of these positions represented another “short term win” and further extended the reach of the SSC DEI volunteer army. Other short-term wins realized with the support of the DEI Fellows included a DEI small grants program created early in the tenure of the DEI Fellows Program, two DEI minors, the aforementioned ad hoc DABDI which was ratified into a permanent standing committee, now called Dean’s Advisory Committee on Diversity and Inclusion. Last, but not least, the Associate Dean’s “From the Desk of . . .” diversity monthly newsletters which celebrate the work of faculty, staff, students, and alumni in the DEI space, is another “short term win” that has been well received by the SSC community. As part of this monthly series, A DEI champion is featured every month in a university-wide publication that is also distributed to alumni.

To create a DEI model at the college-level, the Dean’s DEI Fellows conducted a nationwide review of DEI best practices, structure, and available resources in colleges of Social Science or its equivalent in universities across the nation. The review examined Diversity Champion Universities (as awarded by Insight into Diversity), Big Ten Universities, and other colleges at MSU.3 Their search was focused on three main points:

1. How are their DEI programs conceptualized and whom does it serve?

2. What is the basic structure of these DEI programs and what offices are they in?

3. What kinds of resources are available to these DEI programs?

For several weeks, each DEI Fellow was assigned a few universities to review. We started our search by looking at the university’s position and provisions for DEI at the university level, then college level, and finally individual departments and programs. Starting the review with 2019 Diversity Champion universities, the schools reviewed were Oklahoma State University, Rochester Institute of Technology, Texas A&M, Clemson, Florida State University, Medical University of South Carolina, University of Alabama-Birmingham, University of Cincinnati, University of Kentucky, University of North Florida, Virginia Commonwealth Universities, and University of Louisville. Although these universities are diversity champions, their investment on DEI differs, with some clearly lacking. For example, while some of the reviewed universities had clearly defined DEI offices and operating structures at the university and college levels; others barely had a DEI office, even at the university level.

Focusing on the Diversity Champion universities that are doing better with DEI, the fellows in their findings, identified some contributing factors that propel the success and sustenance of DEI in these universities. Some of the factors and recommendations include:

Having clearly defined DEI goals in the university, college, department, and programs’ strategic plans.

3 Applicants for the Higher Education Excellence in Diversity (HEED) Award are ranked and those in the top tier are considered Diversity Champions.

10

Colleges, departments, and programs that have inclusive teaching strategies, various ongoing initiatives targeted at faculty, staff and students offer better space for DEI to thrive.

Highlighting minoritized and first-generation students. Also, when possible, providing financial support to these underrepresented members of our community.

Creating a climate and inclusive committee. This committee should be dedicated to reviewing college, department, and program policies to make sure that they are inclusive.

Having a way of measuring progress or an annual accountability report.

Each department having a DEI committee, including a representative from the committee who serves on the college DEI committee.

Having initiatives that encouraged the recruitment of minoritized faculty, staff, and students, thus increasing the demographic diversity.

Advancing community engagement programs targeted at minoritized communities.

Establishing mentorship programs for minoritized and first-generation students

Offering course releases and other incentives to stimulate faculty interest in diversityrelated activities.

Since Michigan State University is a Big Ten University, the Dean’s DEI Fellows deemed it necessary to review MSU’s peers. The Big Ten universities reviewed were Purdue University, Ohio State University, University of Wisconsin, University of Illinois, Indiana University, The University of Iowa, University of Maryland, University of Michigan, Penn State University, University of Minnesota, and University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The Dean’s DEI Fellows identified some factors and best practices that ensure the sustenance of DEI in the reviewed universities. Examples of such factors include:

Strategic plans that lay out key areas and initiatives for promoting diversity and inclusion.

Promotion of diversity and inclusion through recruitment, mentoring, retention of minoritized faculty, staff, and students.

Inclusive leadership training courses for faculty, staff, and students.

Creation of culturally relevant mentoring programs and encouraging partnerships with local cultural resource centers.

Creation of centers for research on DEI that could be separate or within colleges that support research on DEI.

An office dedicated to DEI initiatives and implementation.

DEI advisory committee with faculty, staff, and student representation that advises the Dean.

Encourage inclusive pedagogy and research.

Encourage equity and accountability, recognize invisible labor, and establish a better reporting procedure to capture labor put into DEI.

Institutionalize DEI within College Units.

Diversifying the faculty, staff and students through minority hires and scholarships for minoritized students.

Comparing Michigan State University with its closest neighbor and peer, University of Michigan, it is very clear that MSU needs to invest a lot more resources in the promotion of DEI. Looking at University of Michigan’s Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA), a close equivalent of College of Social Science here at MSU, it is obvious that U of M walks the talk. The college has invested both

11

human and financial resources in the promotion of DEI. The college has a functional office for DEI with resources committed to ensure efficacy and results. The office has the Associate Dean for DEI and Professional Development and a diversity manager. The manager supports the Associate Dean in the design and implementation of their strategic DEI goals and other DEI related issues. The LSA DEI office created in 2016 is charged with delivering DEI-related professional development training for faculty, staff and students in the college. They also:

“Provide consultations to students, staff, and faculty on DEI matters,

promote other DEI activities on and off campus that are open to students, staff, and faculty.

support diversity efforts in hiring and retention processes,

create and manage recruitment sources in efforts to diversify candidate pools for staff and faculty positions, and;

develop metrics to measure and evaluate the effectiveness of DEI initiatives.” (UM LSA DEI Office, n.d.).

Comparatively, the SSC at MSU can only boast of an active Associate Dean for DEI. This position comes with no “office” nor staff dedicated to DEI matters. U of M’s establishment of an office offers more guarantee for DEI sustainability as activities are not dependent on individuals. At MSU, the programs introduced by the Dean or Associate Dean for DEI may end with the tenure of that Dean or Associate Dean. Long term goals will be difficult to achieve, as there are no guarantees for sustainability. With this in mind, the Dean’s DEI fellows embarked on crafting an office structure for the College of Social Sciences. Comparing different programs across Big Ten universities was a pivotal first step to the foundational stage “create a sense of urgency” within the organizational change framework.

Revisioning the SSC Office of Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Drawing inspiration from this exploratory and information-gathering process, with the knowledge that “to enable action, change requires removing barriers,” the Dean’s DEI Fellows began work on reimaging and revisioning the existing structure of the College of Social Science’s Dean’s Office so that diversity, equity, inclusion would be present in every part of the Dean’s Office administration. The DEI Fellows enabled action by removing the barrier existing in the form of college leadership. They rejected College leadership’s nonacceptance by forging ahead to publish DEI office structure, crafted based on good data and best practices as a guide for SSC and other institutions. What follows below is the actual “best practices/restructuring” document that the Dean’s DEI Fellows introduced and shared with the Interim Dean of the College of Social Science.

The Associate Dean for DEI Office—Collaborating to Promote an Inclusive SSC

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion is not a standalone entity, but rather should permeate all that we do in the College of Social Science (SSC)—from recruitment and retention to campus climate, curriculum, and instruction, to research, student/faculty/staff success, to leadership development, advancement/development, and external relations (NADOHE, 2020).4 The work crosses multiple

4 See National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education (NADHOE), “Standards of Professional Practices for CDOs, (NADHOE, 2020), standard two, “diversity officers work to ensure that elements of equity, diversity, and

12

domains and requires capacity to ensure a sustainable infrastructure. Therefore, existing administrative structures in the Dean’s Office will have to be re-visioned and new DEI-focus positions created. When there is a mismatch between articulated commitment to DEI and the resources allocated to diversity initiatives, efforts, and offices, there is a potential that DEI work will become a source of tension, conflict, and failure (NADOHE, 2020).

The Associate Dean for DEI (henceforth AD) should necessarily be involved in every theater of operation in the College of Social Science’s Dean’s Office, infusing diversity principles throughout the College with the aim of transforming the culture of the College into a more diverse and inclusive space. Towards these ends, the AD should be bound together with all the other Associate Deans, in a network of inter-dependent relationships of collaboration with shared interests and goals.

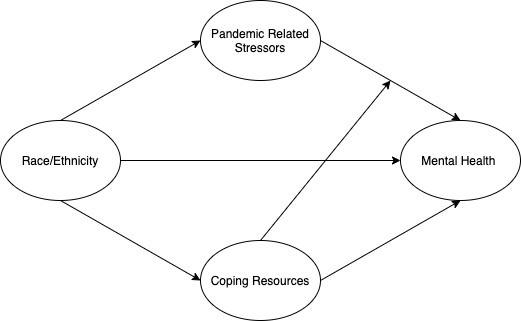

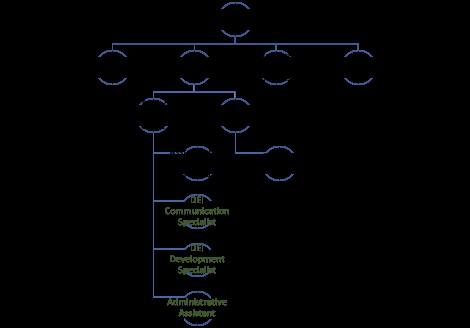

The SSC Office for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusive Affairs (DEIA) should be reintroduced to support and enhance the College’s commitment to creating an inclusive community.5 The Office will be overseen by the AD, assisted by a 1 FTE Assistant Dean for DEI/Associate Director of the Office. The AD will be responsible for the design, structure, and daily operation of the office. The primary mission of the office will be to provide quality support through programs and initiatives that foster a community climate that acknowledges and appreciates a multiplicity of diversities. The Office will be a multi-dimensional site for DEI work with multiple operations and arms collaborating to create a more equitable College for all. Above is a diorama that demonstrates the interconnectivity of DEI work in the Dean’s Office, and below is a narrative that lays out this interconnectivity in more detail.

General Responsibilities

o The AD and Director of DEIA Office oversees, facilitates, and advances all DEI-related interests in the College of Social Science.

o They network and liaise with other administrative units to promote, support, and advance all minoritized members of the SSC community.

o The AD and Director of DEIA liaises with community and academic partners to propel DEIrelated interests.

o The AD and Director of DEIA is an ex-officio member of Dean’s Advisory Committee on Diversity and Inclusion (DACDI) which provides feedback and guidance to the Associate Dean and Dean in addressing diversity-related concerns.

o They are members of CODD (Council of Diversity Deans). The present AD for DEI is founder and co-chair of CODD.

Organizational Chart – Dean’s Office6

inclusion are embedded as imperatives in the institutional mission, vision, and strategic plan,” 8.

5 MSU DEI Leaders—the Colleges of Engineering, Human Medicine, Agriculture and Natural Resources (CANR), Law, Veterinary Medicine, Madison, Communication Arts and Sciences, Natural Sciences (NatSci)—all have DEI offices to support the breadth and depth of the work. SSC established its office in 2005, only to get rid of it after the sitting Associate Dean for DEI left the university.

6 The justification for the above structure, roles, and responsibilities is inspired by the foremost professional organization for Diversity Officers NADHOE’s “Standards of Professional Practice for Diversity Officers” as well as justification from other Colleges at MSU.

13

Faculty Affairs

o The AD and Director of DEIA Office leads efforts to support and advance minoritized faculty members, in collaboration with the AD for Faculty. The AD’s efforts are concentrated on, but not limited to faculty hiring. The complete range of faculty affairs include:

o The AD and Director of DEIA Office leads efforts to support and advance minoritized faculty members, in collaboration with the AD for Faculty. The AD’s efforts are concentrated on, but not limited to:

o Works with search committees and the Dean’s Office in hiring faculty from job advertisements, to search committee trainings, to hire letters.

o Leads the Dean’s Research Associate Program

o Leads the Dean’s Distinguished Senior Scholars Program

o Leads the Dean’s DEI Fellows Program

o Retention, Promotion, and Tenure (RPT)

o Develops RPT Implicit Bias Training for College RPT Committee

o Ex officio member of College RPT Committee

Undergraduate and Graduate Student Affairs

o The AD and Director of DEIA Office leads efforts to infuse DEI into general undergraduate curriculum, including creating two SSC DEI Minors—domestic and international.

o They lead efforts to support and advance minoritized/first-generation undergraduate students, in collaboration with AD Academic and Student Affairs.

14

o The AD will manage all programming designed for minoritized/first generation students including Opportunity Gaps Programming. (Will collaborate with the AD of Academic and Student Affairs to conceptualize a first-generation program for undergraduates, with a middle school pathway program for marginalized students from the Detroit, Flint, Grand Rapids, and Lansing areas.

o The AD and Director of DEIA Office leads efforts to support and advance minoritized graduate students, in collaboration with AD Graduate Studies. (Manages AGEP—the Alliances for Graduate Education and the Professoriate, and Graduate School Pipeline Programs for minoritized students.)

Staff Affairs

o The AD and Director of DEIA Office leads efforts to support and advance minoritized staff members, in collaboration with all Associate Deans and the Dean’s office.

Communications

o The AD and Director of DEIA will collaborate with the Director of Communications and the DEI Communications Specialist in facilitating and mediating all DEI branding and communications on behalf of the Associate Dean/Dean’s office.

o The DEI Communications Specialist will manage DEI communications workload (newsletter, website, social media, journalistic responsibilities in general).

Development

o The AD and Director of DEIA Office will collaborate with the Senior Director of Development and the DEI Development Specialist in advancing and promoting College efforts in DEI development.

o The DEI Development Specialist will manage DEI development, including, working with the AD to attract donors, gifts, etc. from DEI-interested parties, and establish an alumni DACDI giving board.

Assistant

Dean for DEI /Associate Director of DEIA

Office

o The Assistant Dean for DEI /Associate Director of DEIA Office provides student-centered support for minoritized SSC students and facilitates a DEI-affirmative environment among the undergraduate and graduate student populations

o They report to the Associate Dean for DEI, and,

o Work with the Assistant Director DEI Academic Affairs

o Work more broadly with Associate Provost for Undergraduate Education (APUE). Is a liaison to APUE

o With oversight of AD, leads first-generation program.

15

Resources Needed (structural)

1. Percentage time of AD increased to .75 FTE.7

2. Creation of a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusive Affairs (DEIA) Office, with an Assistant Director/Assistant Dean of DEI (staff) at 1 FTE.

3. Space for the DEI Office (safe space for minoritized students, staff, and faculty)

4. 1 FTE administrative assistant

5. .50 FTE grad student assistant

6. 1 FTE Assistant Director of DEI undergraduate and graduate Affairs

7. .50 FTE DEI Communications Specialist

8. .50 FTE DEI Development Specialist

Resources Needed (financial)

1. Budget for DEI Faculty Hiring Initiatives

2. Extend Dean’s Research Associate Program for 5 years

3. Hire three Research Associates each year

4. Five years of unrestricted funds for programming in support for the Dean’s Research Associate Development Institute (DRADI)

5. Extend Dean’s Distinguished Senior Scholars Program for 5 years

6. Hire two Distinguished Senior Scholars each year

7. Unrestricted budget for SSC DEI initiatives $100,000

Theory to Practice: Implementing a Sustainable University DEI Structure

As we reflected upon the steps and processes involved in advocating for a sustainable DEI structure for the SSC, we explored various frameworks that would support our efforts. It was important to utilize a framework to provide empirical evidence in support of the efficacy of a DEI structure. In doing so, we utilized Kotter’s (2012) 8-Step Process for Leading Change, and determined how his processes aligned with our vision for a sustainable DEI structure within our College. An explanation and application of the stages are below.

Step 1: Creating a Sense of Urgency Around a Single Big Opportunity

According to the model, when seeking to institute change in a current structure, “heightening an organization’s awareness . . . and ridding an organization of complacency” (Kotter, 2012, p. 51) is critical. We decided to address the need to implement a sustainable DEI structure due to the very urgency of the moment. Racial inequities and tensions, not limited to the challenges mentioned above solidify the need for a sustainable DEI, structure. The recent racial tensions which forced corporations, workplaces, and society in general to evaluate injustices compelled higher educational institutions to express their solidarity with a rapid sense of urgency that may not have

7 Justification for the request for a higher FTE is that the DEI Associate Deans in CANR/NatSci are hired at 1 FTE, and the DEI Associate Dean in Education, a much smaller college than the College of Social Science is hired at .75 FTE.

16

otherwise occurred. Despite the intent or rationale for institutions moving swiftly, we had to utilize this rationale in order to further our DEI goals. Now that we have the platform, we must take advantage of the opportunity and make clear that implementing a sustainable structure will provide sustenance and support for faculty, staff, and students within our college not just during a “DEI P.R. Crisis.” In short, we are seeking to provide a DEI structure that permeates through every phase, person, and process of our SSC.

Step 2: Building and Maintaining a Guiding Coalition

A Guiding Coalition (GC) comprised of individuals of various levels throughout an organization is crucial to institutional success (Kotter, 2012). Further, each member of the GC should have equal say and input. In our case, the Associate Dean for Diversity purposefully sought to create opportunities for faculty and staff of various levels to contribute to our DEI goals. She created the Dean’s DEI Fellowship Program for that very reason.

Step 3: Forming a Strategic Vision and Initiatives

A strategic vision serves as the North star for the importance of change initiatives. Further, the vision demonstrates the importance of opportunities (Kotter, 2012). In our case, all of the aforementioned steps and processes that we have undertaken have supported our DEI vision. We began the process of undertaking a strategic vision based upon discontent with status quo and piecemeal DEI initiatives. In addition, nationwide evaluations of best DEI practices among other universities have provided insight on DEI effectiveness, as well as DEI necessities that are not being addressed.

Step 4: Enlisting a Volunteer Army

“The Volunteer Army is not a bunch of staff carrying out orders . . . its members are change leaders who bring energy, commitment, and enthusiasm” (Kotter, 2012, p. 56). As we began this initiative, we were not naïve to the fact that implementing institutional change is difficult, challenging, and at times frustrating. As such, it takes individuals who are willing to serve as change advocates - “even if 10% of an organization” (Kotter, 2012, p. 56). Within the SSC, DEI advocates seeking to sustain a permanent DEI structure are small, but mighty. DABDI members provide input, counsel, and suggestions for instituting structural change. DEI Fellows are committed to creating a blueprint for action. The army is small, but the mission is mighty.

Step 5: Enabling Action by Removing Barriers

In order to accelerate movement, those seeking change must ensure that barriers are being removed. In this case, we must ensure that the DEI needle is constantly advancing within the SSC to move beyond DEI statements. In our case, despite lack of resources to advance a sustainable DEI office, we sought to balance short-term wins discussed below in Step 6 with longer term strategies that would support implementation of our envisioned SSC structure.

17

Step 6: Generating Short-term Wins

Short-term wins “should be obvious, unambiguous, and clearly related to the vision” Kotter, 2012, p. 56). Such was the case with several efforts undertaken by the Associate Dean of Diversity for the SSC and the DEI Fellows. We implemented small grants for faculty and students within the SSC. A DEI vision was conceptualized and submitted to the Dean. We have created and proposed two DEI minors and begun with the help of an outside facilitator to develop a DEI strategic plan. Finally, we have produced three manuscripts that outline the DEI processes, challenges, and visions for academic outlets.

Step 7: Sustaining Acceleration

Recognizing that “urgency is central because when an organization takes its foot off the gas, cultural and political resistance arise,” (Kotter, 2012, p. 56) we sustained acceleration as a result of the external pressure generated by the Black Lives Matter movement, the Nassar scandal, the COVID pandemic, as well as the visibility of injustice across the country. All of these culminated into the need for Michigan State University to develop a university wide DEI strategic plan. This plan calls for further work at the college level. We have kept the urgency of developing a sustainable DEI Office at the forefront of our goals and objectives. DEI advocacy cannot be placed on the sidelines, and this served as a motivator to ensure that we continue to hold SSC leadership accountable: advocacy cannot wait.

Step 8: Instituting Change

As mentioned throughout, our goal is to develop a sustainable DEI structure that permeates throughout our SSC. DEI work can be isolating, and difficult to see advancement. With the implementation of a DEI permanent structure, we will institutionalize support that will be visible throughout SSC. Whether or not true transformative DEI change occurs is yet to be seen. We are however hopeful that there will be some change due to the implementation of the university-wide DEI strategic plan, which further calls for college level DEI strategic planning. It is our hope that after these are realized that there will be dialogue around, and implementation of, a structure, roles, and responsibilities plan.

Recommendations

The DEI Office sustainable structure presented here is meant to be a blueprint for advocating and advancing DEI systemic transformation in colleges and universities. As we discovered while conducting the review of structures at other universities, far too often DEI programs are not structurally tied to the organization. This leaves DEI in a vulnerable position where it is at the whim or mercy of the leadership at any given time. Although one could assume that Deans and Chairs have made DEI a priority, the reality, as we found, is that such assumption is not a guarantee. Even when it is expressed in words and slogans, it is not supported by sharing equal power and significant resources.

The eighth stage of Kotter’s organizational change framework affirms that to institute change, it is

18

important to “articulate the connections between the new behaviors and organizational success, making sure they continue until they become strong enough to replace old habits.” In our view developing a structure where DEI is ingrained and connected to the fabric of every major administrative stakeholder, brings more accountability and voice to the priorities necessary for transformative DEI. Beyond inclusion, the proposed blueprint demands that resources be allocated to recognize, reward, and support DEI as a major priority in colleges and universities. This blueprint also establishes legitimacy in DEI leadership through a structural and sustainable approach. Furthermore, this blueprint represents a sharp departure from the idea that DEI is only invoked but not invested. Given our changing and diversifying world and context within higher education, this blueprint also reinforces that leadership and accountability at all levels must also be invested in the transformative process. Finally, such investment advances beyond an institution’s forced commitment to demonstrate performative support of DEI during a time of societal unrest, moving toward transformative commitment and support which is at the heart and connective tissue of operations and decision-making across campus.

References

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press: Durham and London.

Cahalan, M., Perna, L. W., Yamashita, M., Wright-Kim, J. & Jiang, N. (2019). 2019 Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States: Historical Trend Report. Washington, DC: The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, Council for Opportunity in Education (COE), and Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy of the University of Pennsylvania (PennAHEAD).

Carnevale, A.P., Fasules, M.L., Quinn, M.C., and Peltier Campbell, K. (2019). Born to Win, Schooled to Lose: Why Equally Talented Students Don’t Get Equal Chances to Be All They Can Be. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. McCourt School of Public Policy. Downloaded on April 21, 2021 from College of Social Science (2017). Strategic Plan: Fall 2017-Fall 2022. https://socialscience.msu.edu/_assets/pdfs/StratPlan-web-lo.pdf

College of Social Science (SSC) Diversity Matters a (n.d.) Dean’s Diversity Board on Diversity and Inclusion. Retrieved from https://socialscience.msu.edu/diversity/DABDI1/index.html

College of Social Science (SSC) Diversity Matters b (n.d.) Dean’s Research Associate Postdoc Program. Retrieved from https://socialscience.msu.edu/diversity/DABDI1/index.html

College of Social Science (SSC) Diversity Matters c (n.d.) Dean’s Distinguished Scholars Program. Retrieved from https://socialscience.msu.edu/diversity/distinguished-senior-scholars.html

College of Social Science (SSC) Office of the Dean (n.d.). Strategic Plan: Fall 2017-Fall 2022. Retrieved from (https://socialscience.msu.edu/about/strat-plan.html).

Correa, C. & Louttit, M. (2018). More than 160 women say Larry Nassar sexually abused them. Here are his accusers in their own words. New York Times. Downloaded on March 19, 2021 from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/01/24/sports/larry-nassar-victims.html

19

Das, R. (2020). MSU President responds to display at Wharton Center that sparked outrage. WLNS.com. https://www.wlns.com/news/local-news/msu-president-responds-to-display-atwharton-center-that-sparked-outrage/ Evans, T., Alesia, M. & Kwiatkowski, M. (2018, January 24). Former USA Gymnastics doctor accused of abuse. The Indianapolis Star. https://www.indystar.com/story/news/2016/09/12/former-usagymnastics-doctor-accused-abuse/89995734/

Fischer, K. (2019). The Barriers to Mobility: Why Higher Ed’s Promise Remains Unfulfilled. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Downloaded on April 21, 2021 from https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-higher-ed-rsquo-s-promise-remains-unfulfilled/ Guzman, W. (2020). Racist comments in 'Ask President Stanley' online question platform. State News. https://statenews.com/article/2020/02/racist-comments-in-ask-stanley-online-questionplatform Harris, T.M. (2021). Dismantling the trifecta of diversity, equity, and inclusion: The illusion of heterogeneity. In H. Oliha-Donaldson (Ed.), Confronting equity and inclusion incidents on campus: Lessons learned and emerging practices (pp. 34-57). Routledge.

Hauser, C. & Zraick, K. (2018). Larry Nassar Sexual Abuse Scandal: Dozens of Officials Have Been Ousted or Charged. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/sports/larrynassar-case-scandal.html

Holzer, H., and Baum, S. 2017. “Making College Work: Pathways to Success for Disadvantaged Students.” Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Institutional Research, Office of Planning & Budgets. (2021). MSU Data Digest - Faculty and Staff. [Tableau Dashboard]. https://opb.msu.edu/functions/institution/datadigest/. Last updated: 2021-09-09.

Kang, S.P., Chen, Y., Svihla, V., Gallup, A., Ferris, K. & Datye, A.K. (2020). Guiding change in higher education: an emergent, iterative application of Kotter’s change model. Studies in Higher Education, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1741540

Kotter, J. P. (2012). Accelerate! How the most innovative companies capitalize on today’s rapid-fire strategic challenges - and still make their numbers. Harvard Business Review, 90(11). Kotterinc.com (n.d.). The 8-Step Process for Leading Change. (https://www.kotterinc.com/8-stepsprocess-for-leading-change/)

Largent, M. (2019). Riding Tides and Closing Gaps. Report from the Associate Provost for Undergraduate Education at Michigan State University. Downloaded on November 4, 2021, from https://undergrad.msu.edu/news/view/id/215

Matias, J.N., Lewis, Jr., N. & Hope, E. (2021). Universities say they want more diverse faculties. So why is academia still so white? https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/universities-say-they-wantmore-diverse-faculties-so-why-is-academia-still-so-white/ MSU Worklife Office (2020). IDEA Coordinators. https://worklife.msu.edu/node/831

Michigan State University Office for Inclusion and Intercultural Initiatives. (2020). Diversity at MSU, 2019-2020 Annual Student and Workforce Data Report https://inclusion.msu.edu/about/datainformation/2019-20%20Diversity%20at%20MSU%20Student%20and%20Workforce%20Data %20Report.pdf

Office of the President (n. d). Committee Charge and Process. https://president.msu.edu/initiatives/dei-plan/dei-committee-charge.html [accessed March 28. 2021)

20

Office of the President (n.d.). Relationship Violence and Sexual Misconduct Plan. https://president.msu.edu/initiatives/rvsm-plan/index.html

Pendakur, V. (2016). Closing the Opportunity Gap: Identity-Conscious Strategies for Retention and Student Success. Stylus Publishing: Sterling, VA.

Stanley, C.A., Watson, K.L., Reyes, J.M., & Varela, K.S. (2019). Organizational change and the Chief Diversity Officer: A case study of institutionalizing a diversity plan. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 12(3): 255-265.

Thomas, J.M. (2020). Diversity regimes: Why talk is not enough to fix racial inequality at universities Rutgers University Press: New Brunsick, New Jersey.

Tidwell, S. (2019). ELPD investigating destruction of MSU Hillel's Sukkah over the weekend. The State News. Downloaded on March 19, 2021 from https://statenews.com/article/2019/10/msuhillel-sukkah-vandalism-over-the-weekend

UM LSA DEI Office (n.d.). LSA DEI Office. https://lsa.umich.edu/lsa/faculty-staff/lsa-dei-office.html

Walker, C. (2019). Students outraged over MSU response. Downloaded on March 19, 2021 from https://www.wilx.com/content/news/Students-outraged-over-MSU-response-563672791.html

21

Association of University Administrators. Permission to reprint for academic/scholarly purposes is unrestricted provided this statement appears on all duplicated copies. All other rights reserved.

Journal of Higher Education Management, 37(2), 22-38 (ISSN 2640-7515). © Copyright 2022 by the

Hearing Diverse Perspectives: Authentic Signaling in Faculty Recruitment

Brent S. Opall

University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire

Kranti Dugar

University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire

Kevin Hansen

Bellarmine University

Nancy Hanson-Rasmussen

University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire

Bridget Kurtenbach

University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire

Introduction

As modern workplace demographics evolve, issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion are important and timely. A global 2020 survey by McKinsey found that job seekers consider an organization's inclusive practices when making career decisions. Evidence shows workers who feel included are nearly three times more committed to their organization, and current discourse about social injustice has led institutional leadership to prioritize inclusion and diversity (Bailinson, Dechard, Ellsworth, & Guttman, 2020). The workforce is ever more diverse, especially with respect to women, Black, and underrepresented ethnic professionals (Muzio & Tomlinson, 2012; Stevens, Plaut, & Sanchez-Burks, 2008). The greater the differences among employees, the broader their perspectives, the stronger the teams, and the better their resources for problem resolution (Cox, 2001) and ethical decision making (Reidenbach & Robin, 1991). Additionally, Çelik and Çelik (2017) found that visible practices such as diversity policy and interventions can positively impact commitment, retention, and performance, and Singh and Selvarajan (2013) noted that inclusive, supportive climates motivate employees—especially underrepresented employees—to stay with the organization. The signaling or representation of an inclusive organization encourages underrepresented group members to join, and message consistency over time provides for an inclusive workplace. Universities, similarly, need to adapt to changing demographics and effectively signal inclusivity to ensure they serve the needs of more diverse students (Danowitz & Tuitt, 2011; Hurtado, Milem, Clayton-Pedersen, & Allen, 1998).

Diversity in Universities. Academic institutions are working to create cultures of inclusiveness for faculty, students, and leadership. Beyond the classroom, diversity initiatives can have positive behavioral effects for students after leaving the academic setting (Bowman, 2012). However, the question remains as to whether universities are adequately exposing students to the diverse climates and cultures they will encounter upon graduation. Work environments that graduates experience in their first employment opportunity are increasingly diverse (Hu & Kuh, 2003). Tienda (2013) found progress as to the “racial diversification of college campuses” (p. 467) at several universities, indicating improvement from prior studies, which found diversity efforts in early stages

22

American

of development (Clark, 2011; Umbach, 2006). Universities are increasingly expected to prepare students from different backgrounds to live and work in a diverse society (Hurtado, Milem, ClaytonPedersen, & Allen, 1999; Orfield & Whitla, 1999).

Defining diversity in a manner that is appropriately encapsulating is important to both identifying members of diverse groups and working to meet the needs of each group. For this study authors adopted, “the inclusion of people of different races” (Merriam-Webster, 2021). Additionally, deeplevel diversity has been defined as including “attitudes, opinions, information, and values” (Phillips & Loyd, 2006, p. 143). Tienda (2013) suggested that the term diversity could reflect “myriad dimensions – cultural, political, economic, and … racial” (p. 468).

For this study, underrepresented individuals come from minority groups such as people of color; people who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender; people with disabilities; people of a nondominant religion; and retirees (Allen, 2017). Women were considered as underrepresented if they self-identified as such in their profession, and the authors also considered veterans as underrepresented. This study intentionally focused on the perspectives of and feedback from diverse, prospective faculty members and did not compare and contrast responses to those from all prospective faculty members.

Efforts to Recruit Diverse Candidates. Universities are dynamic networks of people (Mea & Sims, 2019) that strive to prepare students for successful careers and provide a framework for conducting business through ethical practice. Because business prosperity is now recognized as occurring in a dynamic environment, academic institutions are working to employ faculty that reflect the demographics of contemporary businesses and are trying to increase efforts to hire diverse candidates. Historically, white faculty members have held most positions in higher education, as compared to diverse counterparts (Kayes, 2006). A 2017 National Center for Education Statistics study evaluating the racial and ethnic makeup of faculty found that 5% of college faculty members were Hispanic, 6% were Black, and 11% identified as a member of an Asian race (Davis & Fry, 2019). The same study also found only 19% of tenured professors were nonwhite (Black, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islanders, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and those of two or more races) whereas 27% of non-tenured faculty (i.e., tenure-track assistant professors) were nonwhite. Instructional staff and lecturers were 24% and 20% nonwhite, respectively (Davis & Fry, 2019). Fairlie, Hoffmann, and Oreopoulos (2014) found that only 9.6% of full-time instructional faculty are Black, Latino, or Native American, and gender disparities have previously been documented for faculty in universities (Danowitz & Tuitt, 2011). Savitz (2013) noted that having a workforce that mirrors the diversity of the communities served can aid university leadership in more successfully serving those communities. Increasing diversity among faculty has the additional potential to increase diversity within university leadership and university committees.

To improve diversity of faculty, administrators need to make concerted efforts to revamp recruitment, hiring, and retention programs (Clark, 2011). A 2016 case study found that half of the academic institutions surveyed viewed hiring diverse new faculty as a business case to better adapt to the multicultural work settings their students face upon graduation, no matter their academic discipline (Vos, Çelik, & de Vries, 2016). Increased diversity efforts at universities are also important because of competition across institutions (Teixeira, Rocha, Biscaia, & Cardoso, 2012), and such

23

efforts could procure a competitive edge. Kayes (2006) also noted the importance of university leadership in “attracting, hiring, and keeping faculty and staff of color” (p. 65), and these campus leaders need essential skills to recruit, mentor, and support diverse faculty (Moses, 2012). Having a diverse and inclusive university leadership team setting the direction and strategy of an academic institution can also have a positive effect on the retention of diverse students (Fincher, Katsinas, & Bush, 2010; Hitt, Ireland, & Hoskisson, 2001).

Theoretical Framework

As administrations work to diversify faculty and build inclusive environments, institutional values are communicated using overt and covert messages while recruiting. These communications signal the university’s values, intentions, and actions to candidates, as noted in signaling theory, and the receiver of the messages determines whether they match expectations or experiences (Cook & Glass, 2008; Rynes, Bretz, & Gerhart, 1991; Spence, 1973). If messages match, there is symmetry; but, if messages are in conflict, asymmetry results (Spence, 1973). A college that offers domestic partner benefits but does not have a nondiscrimination policy could signal asymmetry and lack of commitment to full diversity (Cook & Glass, 2008).

Most signaling occurs through messages that are intentionally positive and convey positive attributes (Connelly, Certo, Ireland, & Reutzel, 2011). Suazo, Martinez, and Sandoval (2009) suggested that signaling theory is evident when sending positive cues to applicants related to values and diversity efforts. Candidates interpret signals and draw inferences about the organization’s actions, especially when prospective candidates have imperfect, non-observable information (Rynes et al., 1991). When possible, a better condition for signaling is a realistic job preview, where candidates visit the organization and see true representations of working there (Rynes et al., 1991). Initial recruitment episodes expose applicants to signals at the individual level (e.g., recruitment interviews and word-of-mouth endorsements) and the organizational level (e.g., corporate advertising and recruitment advertising) (Celani & Singh, 2011). The signal forms a psychological contract, where the message received by an applicant is perceived as a reciprocal promise between themselves and the organization (Suazo et al., 2009).

Signaling a welcoming culture that is equitable, diverse, and inclusive is not enough to successfully recruit and hire underrepresented candidates. Many university degree programs, like that in business schools have historically had an underrepresentation of women and racial/ethnic faculty members (Milano, 2005), with faculty in many schools not representing the demographics of their students (Betancur & Livingstone, 2018). This discrepancy is problematic when research suggests students are better prepared for leadership and professional competitiveness when exposed to diverse perspectives in the classroom (Taylor, Apprey, Hill, McGrann, & Wang, 2010).

During recruitment efforts, many candidates consider a university’s retention rate of underrepresented faculty members. In the case of underrepresented instructors, “lack of fit” or “better opportunities elsewhere” are often part of the narrative in climate surveys (Dutt-Ballerstadt, 2020). However, the Higher Education Research Institute found these narratives inaccurate and members of marginalized or vulnerable groups report feeling stressed, discriminated against, and perceiving they must work harder than their colleagues to be viewed as legitimate scholars (Planas,

24

2019). Signaling a warm and inclusive culture when true reasons for turnover are not public may lead to inaccurate signals and eventual feelings of betrayal.

Methods

This study used a qualitative, descriptive, collective case study design (Yin, 2014) for empirical inquiry to evaluate recruitment efforts pertaining to one or more individuals (Stake, 2005). Recommendations from Yin (2014) were followed to ensure quality through construct validity and reliability. To overcome concerns of construct validity, two steps were taken: (a) study phenomena were explicitly defined and related to original objectives of the inquiry, and (b) operational measures were identified, matching said phenomena (Yin, 2014). For construct validity purposes, a detailed case study protocol was used, including definitions of key phenomena, a semi-structured interview template, and a coding manual. Researchers documented each step of the process according to the defined case study protocol for reliability. Interrater reliability was addressed by employing three researchers to code interviews and measure consistency across coding.

To better understand how universities can increase interest and recruit underrepresented faculty, this study used signaling theory to explore: (1) how academic institutions can generate interest in faculty positions among underrepresented groups, and (2) the best methods to accurately convey an commitment to diversity.

Recruitment and Participants

This study was conducted a regionally accredited university in the Midwest of the United States. Purposeful sampling utilized in qualitative research (Creswell, 2013; Miles & Huberman, 1994), allowing researchers to speak to people with first-hand knowledge of key questions explored, enabled information-rich cases (Palinkas et al., 2015) in the current study. Study participants selfidentified as underrepresented in their field, held or were pursuing advanced degrees, and indicated they would pursue a college faculty position. Participants were solicited through: (1) invitations to organizations whose membership included the target population (e.g., Prospanica, National Black MBA); (2) email invitations to alumni of the research university; and (3) invitations on social media sites (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn). Invitations outlined the study, profile of desired interview participants, anticipated time commitment, and interview procedures. Participants selfselected by following a link embedded in the invitation to complete an online Qualtrics survey, which identified qualified participants and collected demographic (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity) and contact information.

Once identified, participants were then asked to indicate their specific field of work and self-identify as underrepresented based on their gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or any intersectionality; researchers did not apply demographic and occupational classifications to participants. Maximum variation sampling based on the predetermined criteria increased the likelihood of findings reflecting different perspectives related to equity, diversity, and inclusion. Additionally, negative cases were included in analyses, which demonstrated differing viewpoints with sharp contrasts to the major pattern or body of evidence. Including negative cases enhanced

25

initial analyses by enabling identification of new themes, providing alternative explanations (Charmaz, 2006), and aiding in data triangulation (Creswell, 2013).

Once the criteria for rigor were met, researchers conducted 45- to 60-minute interviews in person or by phone. Using a semi-structured format, questions covered topics such as perceived barriers to college-level teaching, ways in which participants evaluated a university’s diversity and inclusion, motives behind wanting to pursue a faculty position, and how colleges could support individuals in instructional roles.

Procedures

Forty-four subjects selected their preferred interview location. Interviews were not recorded; instead, the investigators took extensive, detailed field notes which were de-identified (e.g., subject name, employer). De-identified data were uploaded to NVivo, a qualitative data analysis tool, to be organized, coded, and analyzed for themes.

While subjectivity is an inherent part of qualitative research, Peshkin (1988) suggested this should be acknowledged and that researchers should systematically seek out their subjectivity during the research process, not retrospectively. In this study, researchers held reflexivity (Grigsby, 2004) as being central to strengthening the premise by acknowledging their own subjectivity, selfpositioning, and passion toward the topic of inquiry, manifested by their backgrounds, work experiences, life and cultural experiences, experiences of diversity, and history (Wolcott, 2010). Standards of rigor (Davies & Dodd, 2002) and strategies for trustworthiness (Creswell, 2013; Onwuegbuzie & Teddlie, 2002) were employed in analyses to increase reliability of results, including triangulation of methods and data, peer reviews and debriefing, member checking, rich and thick descriptions, audit trails, checking for representativeness of sources of data, detailed documentation, and referential adequacy.

Data Analysis. Data were analyzed through data reduction, data display, and conclusion-drawing and verification. To convert raw data into a valid structure (i.e., data reduction), an organized approach was implemented that involved preliminary sorting and coding during the uploading process. Qualifying interview transcripts were first organized by how the participants self-identified their underrepresentation (e.g., race, gender). Next, transcripts were titled following a naming hierarchy using colors and letters (e.g., Green C, Purple B) to avoid assumptions. This same hierarchy was used to report results (e.g., Orange B (OB), Yellow A (YA)). Finally, data were organized and checked for accuracy.

To complete data display, each interview transcript was individually coded for themes (e.g., identified barriers) using categorical aggregation. Pre-formulated codes rooted in the literature were developed based on the research questions and achieved from direct interpretation, leading to categorization of responses. When reviewing the data, unexpected themes emerged, consistent with qualitative case studies. Analyses included case contexts, descriptions, within-case theme analyses, cross-case theme analyses, assertions, and generalizations. Through multiple examinations, pre-assigned codes were assigned and additional codes were developed and placed

26

as themes emerged. After finalizing coding, patterns and relationships between the codes were expanded upon and clarified, ultimately leading to the development of overall themes.

Fleiss’ Kappa. Given multiple researchers collecting, transcribing, and coding the data, interrater reliability was considered as a measure of proportion of agreement beyond that expected from chance (Sim & Wright, 2005). Fleiss’ kappa (Fleiss & Cohen, 1973) was used to quantify reliability, as it applies to studies using multiple raters and is commonly used to measure raters’ agreement (Fleiss, Levin, & Paik, 2003). In contrast, Cohen’s kappa is a better fit for reliability between two researchers. Fleiss’ kappa was used to measure interrater reliability for identified themes from participants: (1) desire to share knowledge, (2) mentoring, (3) signs/signals of deep-level diversity, (4) diversity encompassing multiple traits, and (5) obstacles to employment inclusion. Three fixed coders were selected randomly from an available pool of six possible coders per assumptions in Fleiss’ kappa. To quantify results, the Fleiss et al. (2003) strength of agreement measures were used: <.4 = poor, .41 – .75 = fair to good, .75 – 1.0 = very good. For assessment of interrater reliability using Fleiss’ kappa, all 44 records were included.

Results

The demographic composition of study participants (n = 44), as self-identified by each participant from initial questionnaires, is displayed in Table 1. Additionally, one participant self-identified as not being underrepresented in their professional field. Final analyses included 44 interview transcripts and over 125 pages of text.

Using the Fleiss et al. (2003) categorizations for kappa, the “desire to share knowledge” and "mentoring” themes were found to be in the "fair to good” level (.41 - .75 range) for strength of agreement. "Signs/signals of deep-level diversity” and "diversity encompassing multiple traits” were found to be at the "very good” level (.75 – 1.0 range).

Why Participants Want to Teach: Messages and Signals. The most important attribute of a teaching role identified by participants in describing their interest in teaching was the importance of spreading knowledge (32% of participants). Additionally, participants emphasized the importance they placed on the work environment, their personal admiration for teachers, and enjoying the job.