MAGAZINE OF SANTA BARBARA BOTANIC GARDEN Ironwood ISSUE 33

Ironwood

Volume 33 | Spring/Summer | 2023

Editor-in-Chief: Jaime Eschette

Editor: Brie Spicer

Designer: Kathleen Kennedy

Staff Contributors: Hannah Barton; Michelle Cyr; Jaime Eschette; Kylie Etter; Joan Evans; José Flores; Denise Knapp, Ph.D.; Keith Nevison; Scot Pipkin; Zach Phillips, Ph.D.; Rikke Reese

Næsborg, Ph.D.; Jordan Sanderson; Dylan Schuyler; Christina Varnava; Laiken Warner; Steve Windhager, Ph.D.

Guest Contributors: Melinda Palacio, David Starkey

Ironwood is published biannually by Santa Barbara Botanic Garden.

As the first botanic garden in the nation to focus exclusively on native plants, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden has dedicated nearly a century of work to better understand the relationship between plants and people. Growing from 13 acres in 1926 to today’s 78 acres, the grounds now include more than 5 miles of walking trails, an herbarium, a seed bank, research labs, a library, and a public native plant nursery. Amid the serene beauty of the Garden, teams of scientists, educators, and horticulturists remain committed to the original spirit of the organization’s founders — to conserve native plants and habitats to ensure they continue to support life on the planet and can be enjoyed for generations to come. Visit SBBotanicGarden.org.

The Garden is a member of the American Public Gardens Association, the American Alliance of Museums, the California Association of Museums, and the American Horticultural Society.

©2023 Santa Barbara Botanic Garden. All Rights Reserved.

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden

1212 Mission Canyon Road Santa Barbara, CA 93105

Garden Hours

Daily: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Members’ Hour: 9-10 a.m.

Phone: 805.682.4726

Development: ext. 103

Education and Engagement: ext. 161

Membership: ext. 110

Nursery: ext. 112

Registrar: ext. 102

Volunteers: ext. 119

Board of Trustees

Jeremy Bassan

Sarah Berkus Gower

Sharon Bradford

Frank W. Davis, Ph.D.

Mark Funk, Board Chair

John Gabbert

George Leis, Vice Chair

Leadership Team

Contents

1 Director’s Message

3 Using Pollinator Networks To Recover Whole Ecosystems

8 A Closer Look at Island Mallow (Malva assurgentiflora)

13 The Unseen Ecology of Dirt: The Story of Mycorrhizae

18 The Ecology Process: The Unusual Techniques Scientists Use To Study Ecosystems

22 The Bug Report: A Plant Is Worth a Thousand Bugs

39 Why Our Living Collection Matters

42 The Garden’s Impact

44 From the Archives: The Art of Research

46 Volunteer Story: From Behind the Lens

Bibi Moezzi, Treasurer

William Murdoch, Ph.D.

Helene Schneider

Warren Schultheis

Kathy Scroggs, Secretary

Ann Steinmetz

Nancy G. Weiss

Denise Knapp, Ph.D., Director of Conservation and Research

Jaime Eschette, Director of Marketing and Communications

Jill Freeland, Director of Human Resources

Keith Nevison, Director of Horticulture and Operations

Melissa G. Patrino, Director of Development

Scot Pipkin, Director of Education and Engagement

Steve Windhager, Ph.D., Executive Director

Join Our Garden Community Online

Sign up for our monthly Garden Gazette e-newsletter at SBBotanicGarden.org and follow us on social media for the latest announcements and news.

49 Field Notes: Poetry Inspired by Nature

50 The Book Nook

51 Budding Botanist: At-home Ecology

On the cover: Little bear beetle (Paracotalpa ursina) on California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum) in Carrizo Plain National Monument (Photo: Kylie Etter)

@SBBotanicGarden

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden

With each new issue of Ironwood, I have had the pleasure of opening this dialogue with you, our growing community of native plant advocates and friends. Historically, I’ve used this space to look back and celebrate the progress we’ve made together toward our mission of conserving native plants and habitats. Santa Barbara Botanic Garden membership recently passed 6,000 households, which is an all-time high, and our attendance continues to top out at our county-imposed 110,000 annual guest capacity limit. We have seen significant growth in our staff, which has come with continued improvements to the Garden itself, including the introduction of the Backcountry a year ago this month! Alone, all of these achievements are incredible, but together they are setting the stage for the Garden’s future. Thank you so much for your support on this journey.

Without you, we never could have accomplished so much — and we certainly wouldn’t be ready to set into motion one of the biggest initiatives in the Garden’s history!

If we’re to continue to make progress in achieving our mission, we must refine our focus and look at new ways to extend our impact beyond the boundaries of the Garden’s 78 acres (31 hectares).

And I’m excited to say that our road map is ready and we’re already underway. Recent research tells us that with enough of the right plants in our landscapes, our urban, suburban, and rural zones can provide critical habitat to ensure that the widest number of species are able to survive, despite stressors of a highly variable climate and continued development pressure. Based on this research, the Garden has set a goal — and is developing strategic programs — to achieve 30% coverage of native plants in residential, commercial, and public landscapes across the central coast, which will support local ecosystems and healthy biodiversity. To maximize our impact, we’ll be launching a multilayered Plant With Purpose initiative, which will enable us to broaden our outreach by offering programs that bring the Garden’s expertise directly to you in several different ways.

1. Training landscape professionals and the general public in the selection and care of native plants

2. Working with volunteer groups and regional parks departments to establish native plant habitats in city and county parks throughout Santa Barbara County

3. Improving the Garden’s online resources and outreach efforts

4. Expanding our efforts to promote native plant use through local and regional policy initiatives

Together, the components of our Plant With Purpose initiative will help us overcome many of the barriers to native plant adoption and lead to greater utilization of native plants in all types of landscapes in our region. Ultimately it will create a community where the health and well-being of people and the planet thrive.

In this issue of Ironwood, we’re exploring the idea of plants with a purpose by looking closer at ecology and some of the nuanced connections that support the web of life, from our research on pollinator networks, a spotlight on the island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora), and the unseen ecology in the “dirt” to some of the processes we use to study all of this and why our Living Collection matters. We hope this issue inspires you to join us as we work together to Plant With Purpose — ultimately, healing and protecting the planet so we can leave it better than we found it for future generations.

Are you ready to grow?

Steve Windhager, Ph.D. Executive Director

Ironwood 1

Director’s Message

2 Ironwood

Using Pollinator Networks To Recover Whole Ecosystems

By: Denise Knapp, Ph.D., Director of Conservation and Research

About 87% of the world’s flowering plants need insects and other animals to pollinate them in order to reproduce. That is why the growing evidence for pollinator decline in many places of the globe, including California and the rest of the American West, is of real concern. Now, what if the plant needing pollination is rare? Could be double trouble. At Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, one of the many ways that we work to conserve and recover our region’s rare plants is by investigating and understanding their pollinator networks. Networks are also a useful tool to assess environmental health. It’s “the interactions between organisms that breathe life into ecosystems,” explains one of my favorite scientific papers, “Conservation and restoration of plant-animal mutualisms on oceanic islands” by Christopher

N. Kaiser-Bunbury, et al.

Pollinator networks reveal not only the animals visiting our rare flowery friends but also the animals using the rare plants’ neighboring plants. This helps us to understand the connections between all of these different organisms. For the rare plant, it reveals 1) whether it has enough different kinds of visitors to be resilient to change, 2) what the priority pollinators are that can be supported to boost its pollination services, and 3) which more common plants attract those priority pollinators. Networks also point to pollinator species that visit a lot of different plants in the area and thus may be important for supporting pollination services in general. In fact, these generalist species have been called the linchpins of networks, since they help keep the system robust to environmental changes — that’s especially important these days.

The Garden’s Invertebrate Ecology Team or “bug team” as they are affectionately called internally, together with collaborator Jenny Hazlehurst, Ph.D., from California State University, East Bay, recently investigated the pollinator networks of five different rare plants on San Clemente Island, located west of San Diego and owned by the U.S. Navy. Those rare plants are the angelic white San Clemente Island larkspur (Delphinium variegatum ssp. kinkiense), the delicate San Clemente Island woodland star (Lithophragma maximum), the creamy San Clemente Island bush mallow (Malacothamnus clementinus), the marvelously magenta southern island mallow

(Malva assurgentiflora ssp. glabra), and the little lilac-colored island rockcress (Sibara filifolia). This work took us to different habitat types and populations scattered around the island, including within the actively bombed Shore Bombardment Area, otherwise known as SHOBA. (We of course had to wait for a day when they weren’t bombing.) Over six visits in spring 2019 and at each of seven sites, Dr. Hazlehurst and Stephanie Calloway, our conservation technician, (with help from me and Casey Richart, Ph.D., the Garden’s first invertebrate ecologist) surveyed 10 plots, each 6.5-by-13 feet (2-by-4 meters) containing these rare plants for 30 minutes each.

The plant that was the big winner for flower visitors was the southern island mallow (figure 1a), which attracted 18 different unique species — from bees and wasps to flies and beetles (figure 1b). This is great news for a plant that is only found in a few locations on Earth. Two bees that visited this mallow more than most (as noted by the thicker segments connecting the pollinator to the plant in figure 1b) were the bindweed turret bee (Diadasia bituberculata) and the metallic green sweat bee (Agapostemon texanus). You can see how well the turret bee fits into the flower (figure 2), undoubtedly getting covered in pollen to ferry to the next plant. Both bee species also

Opposite: A cactus chimney bee (Diadasia australis complex) gathers pollen from a coast cholla (Cylindropuntia prolifera) (Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

Opposite: A cactus chimney bee (Diadasia australis complex) gathers pollen from a coast cholla (Cylindropuntia prolifera) (Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

Ironwood 3

1a: Southern island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora ssp. glabra) (Photo: Stephanie Calloway)

visit the much more common island false bindweed (Calystegia macrostegia) (figure 3). Since this is an easy plant to grow, the Navy planted more of it to support the bindweed turret bee on San Clemente Island.

On the other end of the spectrum was the sweet little island rockcress (figure 4), which did not receive any flower visitors, despite hours of searching. Luckily, the rockcress can self-pollinate — although any plant benefits from mixing genes from time to time (inbreeding isn’t good for plants any more than it is for humans). Since our survey, another group who maps and monitors rockcress populations regularly on San Clemente Island observed three small insects visiting it: large-tailed aphideaters (Eupeodes volucris), which is a type of flower fly, soft-winged flower beetles (Family Melyridae), and a type of predatory thrips (tiny, slender insects with fringed wings) in the Genus Aelothrips. The hairy little flower beetles appear to be a good fit for the rockcress, and typically this family is fairly abundant; hopefully they are doing the job for the endangered island rockcress.

We were really hoping to find Greya politella moths on the San Clemente Island woodland star, since we know that they have evolved together and have a specialized relationship. This relationship benefits both the moths, which will only lay eggs in woodland star flowers, and the flowers, which get pollinated (and only lose a few seeds in the process). We weren’t allowed to go at night into the bombed canyons full of cactus (go figure), but that is when many moths are active — so we purchased the most advanced remotely triggered camera system we could find. Despite steep slopes and technical difficulties, Calloway got images of two different woodland star visitors: the southern-Channel-Islands-endemic urbane digger bee (Anthophora urbana clementina) and the widespread generalist alfalfa looper (Autographa californica) moth, which you can see in figure 5. Alas, there were no Greya moths, which have never been recorded on the island.

That alfalfa looper moth also came into play with another of our rare plants, the San Clemente Island larkspur. In this case, not only did the adult moth visit the rare flower to drink nectar but its larval stage (known as a caterpillar for moths and butterflies) also visited the larkspur to eat the plant itself (figure 6a, 6b). Dr. Richart raised a caterpillar to adulthood in our lab to confirm its identity. Is the alfalfa looper having a net positive or negative effect? We’d need to study more to find out. Photos seem to indicate, though, that the moth is able to drink nectar with its long proboscis (mouthparts) without getting any pollen on it. Chances are, it’s not one of the larkspur’s better helpers.

The endemic urbane digger bee, which has such a lovely and unusual rusty color (figure 7), may be

1b: Chart showing which pollinators visited which plants during spring 2019 research on San Clemente Island

2: A bindweed turret bee (Diadasia bituberculata) visits a southern island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora ssp. glabra).

(Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

3: The bindweed turret bee (Diadasia bituberculata) visits island false bindweed (Calystegia macrostegia).

1b: Chart showing which pollinators visited which plants during spring 2019 research on San Clemente Island

2: A bindweed turret bee (Diadasia bituberculata) visits a southern island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora ssp. glabra).

(Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

3: The bindweed turret bee (Diadasia bituberculata) visits island false bindweed (Calystegia macrostegia).

4 Ironwood

(Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

important as a pollinator of several rare island plants. Not only was it documented visiting the woodland star but also the larkspur, bush mallow, and southern island mallow. This would be a good pollinator for the Navy to keep an eye on, both for its endemism and its likely importance as a pollinator. They should not only make sure that it has enough nectar sources but also that it has enough bare soil to nest in. The digger bee, like about 70% of our other native bees, is a ground nester.

Bees range from generalists that will use many types of plants, like our urbane digger bee and the European honeybee (Apis mellifera), to specialists that will only use a small group of plants, like mallows, cacti (Family Cactaceae), or sunflowers (Genus Helianthus). But it’s been shown that on islands, generalists are typical. It makes sense, since it’s hard enough to disperse to a remote island, let alone find your favorite plant. In one way, this is good news for the islands’ resilience to ecological change. But in another, the loss of a few super-generalists could spell doom for the plants that

4: Island rockcress (Sibara filifolia) (Photo: Denise Knapp, Ph.D.)

5: An alfalfa looper (Autographa californica) moth visits the San Clemente Island woodland star (Lithophragma maxima).

4: Island rockcress (Sibara filifolia) (Photo: Denise Knapp, Ph.D.)

5: An alfalfa looper (Autographa californica) moth visits the San Clemente Island woodland star (Lithophragma maxima).

Ironwood 5

(Photo: Stephanie Calloway)

depend on them. This is a good reason to keep an eye on the urbane digger bee.

Another important generalist flower visitor on the island may surprise you: it’s a fly. Or rather, several kinds of flies, known as flower flies in the Family Syrphidae. One species, Copestylum avidum, was found at every site, while another, Copestylum marginatum, was found at all but one site. Flower flies visit four out of five of our rare plants: the larkspur, bush mallow (figure 8), island rockcress, and southern island mallow. Furthermore, two different kinds of flies called bee flies (Genus Bombylius) visited both the larkspur and the bush mallow. Flies (Order Diptera) are the second most important order among flower-visiting insects worldwide. In some circumstances, they may equal or rival bees as effective pollinators. Furthermore, they can be much more abundant, and many visits may add up to the same amount of service. More research is needed to determine whether the flower flies and bee flies on the island are good pollinators compared to the local bees, but it seems that this is another important group for conservation.

6a: The alfalfa looper (Autographa californica) larva munches the San Clemente Island larkspur (Delphinium variegatum ssp. kinkiense). (Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

6b: The alfalfa looper (Autographa californica) adult moth sips nectar from the San Clemente Island larkspur (Delphinium variegatum ssp. kinkiense). (Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

6a: The alfalfa looper (Autographa californica) larva munches the San Clemente Island larkspur (Delphinium variegatum ssp. kinkiense). (Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

6b: The alfalfa looper (Autographa californica) adult moth sips nectar from the San Clemente Island larkspur (Delphinium variegatum ssp. kinkiense). (Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

6 Ironwood

7: The urbane digger bee (Anthophora urbana ssp. clementina) visits a liveforever (Dudleya ssp). (Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

Of course, not all floral visitors are effective pollinators, and even among pollinators, different degrees of pollination services are provided. Photographs can be a great way to get a first sense of how well an insect can do the job, as we’ve shown here. We take as many photographs of these interactions as we can, which helps to generate hypotheses about which visitors are the most important pollinators. These hypotheses help us to design and pursue further studies where we investigate the amounts, and types, of pollen an insect carries to determine how effective they are as pollinators. In 2024, we’ll be following up with both the San Clemente Island woodland star and the island rockcress to survey and collect flower visitors. We’ll also then investigate pollen loads using a combination of microscopy and DNA barcoding. There is always more to explore and understand and so, the conservation journey continues. O

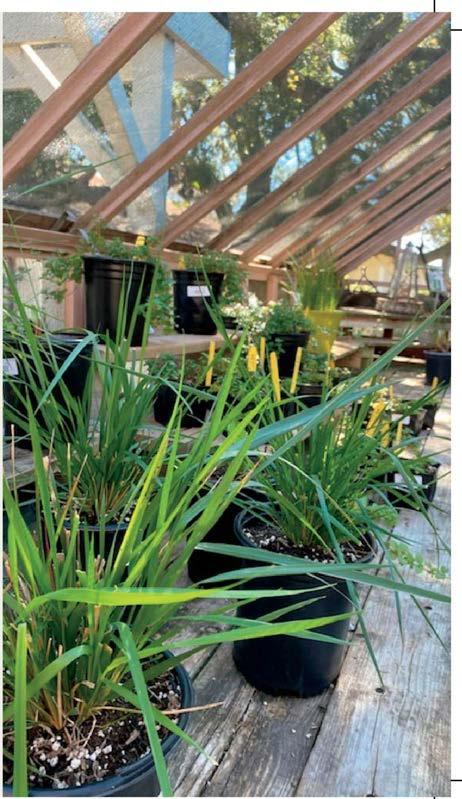

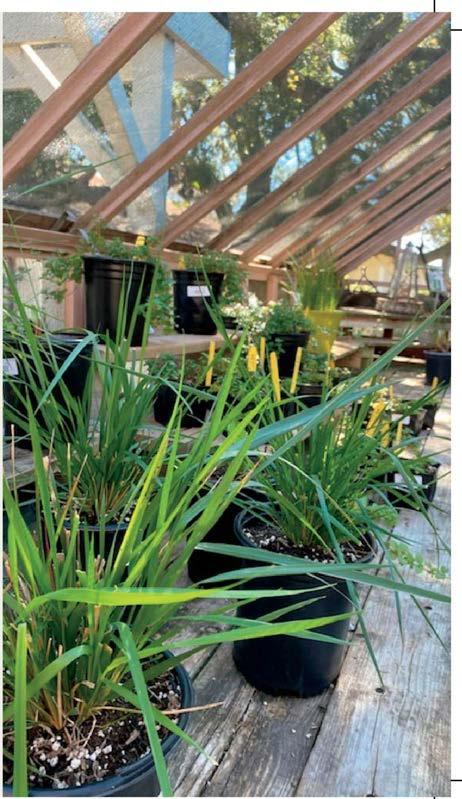

The Garden Nursery

Located in our courtyard, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden

Nursery is open to our members and the public seven days a week, featuring the largest selection of California's native plants on the central coast. With hundreds of varieties available, there is something for everyone.

Garden members receive 10% off every purchase!

8: A flower fly (Family Syrphidae, Genus Copestylum) visits the federally endangered and endemic San Clemente Island bush mallow (Malacothamnus clementinus).

(Photo: Cedric Lee)

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden

8: A flower fly (Family Syrphidae, Genus Copestylum) visits the federally endangered and endemic San Clemente Island bush mallow (Malacothamnus clementinus).

(Photo: Cedric Lee)

Santa Barbara Botanic Garden

to shop.

4:30

HOUR

- 10 a.m. Ironwood 7

Scan

Nursery Hours DAILY 10 a.m. to

p.m. MEMBERS’

9

A Closer Look at Island Mallow (Malva assurgentiflora)

By: Keith Nevison, Director of Horticulture and Operations

By: Keith Nevison, Director of Horticulture and Operations

Flanking the Pritzlaff Conservation Center on Santa Barbara Botanic Garden’s eastside are strikingly beautiful, tropical-ish plants with a unique connection to our Conservation Team going back decades. Although semi-common in the nursery trade today, island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora), aka malva rosa, royal mallow, or mission mallow, is endemically native only to several California Channel Islands, including the northern islands of San Miguel and Anacapa, and the southern islands of Catalina and San Clemente. Island mallow plants form into two distinct subspecies: assurgentiflora and glabra, with the northern island populations grouped in the former and the southern island plants representing the latter. The subspecies assurgentiflora is a taller, tree-like plant that can reach 12 feet (over 3 meters) tall with maturity, while the southern subspecies glabra is shorter in stature with larger, glossier, and smoother (glabrous) leaves.

Island mallow is currently listed as seriously threatened in California (1B.1) on the California Rare Plant Rank scale due to once widespread grazing by feral and domesticated livestock, which were deliberately introduced to the islands more than a century ago. Thankfully, many of these animals were removed from the islands over the past decade, giving plants the chance to recover and for researchers to step up their restoration efforts to recover the species. In 1992, Steve Junak, then the Garden’s Clifton Smith Herbarium curator, and Sarah Chaney, an experienced Channel Islands National Park ecologist, collected seeds of island mallow from

middle Anacapa Island from the last remaining island mallow plants there. Those plants subsequently declined, and Anacapa’s natural populations of island mallow were declared as extirpated or extinct. Restoration work since that time, however, has reestablished appropriate ecotypes of island mallow back on east Anacapa Island, and this work would not have been possible without the collaborative efforts of the National Park Service and the Garden’s joint collection, propagation, and dissemination efforts.

Historically, collections of island mallow that trace genetically from Anacapa Island were planted through many parts of coastal California, from the Bay Area down to Baja California, Mexico, as a garden ornamental and a windbreaking hedge. We find that it performs excellently in our conservation beds surrounding our Island View Section, where it blooms profusely, through many months of the year. Island mallow is a fast-growing plant, best adapted for full sun and low water, and it is listed as a probable host plant for 15 different species of butterflies, moths, and skippers, according to the California Native Plant Society’s Calscape database. Oddly enough, given its rarity and the narrowness of its native home range, island mallow is documented as an escapee in other coastal parts of the world, including Guatemala, western South America, and Oceania. Fun fact: Island mallow is listed as the only Malva that is native to the United States, while seven other nonnative species are listed as being naturalized in Santa Barbara County.

From left: Flower of Coronado Island tree mallow (Malva occidentalis) taken on Guadalupe Island (Photo: Matt Guilliams, Ph.D.); northern island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora ssp. assurgentiflora) growing at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden (Photo: Matt Guilliams, Ph.D.); flower of Purisima island mallow (Malva ‘Purisima’), which is a hybrid between northern island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora ssp. Assurgentiflora) and San Benito Island mallow (M. Pacifica) (Photo: Matt Guilliams, Ph.D.)

8 Ironwood

Opposite: Flower of northern island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora ssp. assurgentiflora) from the Point Bennett area of San Miguel Island, where a small population of a few hundred, naturally occurring plants is slowly recovering from historical land uses during the ranching era (Photo: Matt Guilliams, Ph.D.)

Ironwood 9

A few garden cultivars exist for island mallow, including some borne from hybrid crosses with Malva pacifica, a species native to the islands off Baja California, and from M. occidentalis, a species exclusively endemic to the Coronado Islands off the coast of the U.S./Mexico border, and to Guadalupe Island, an island located over 160 miles (257 kilometers) approximately west of the provincial boundary between Baja California and Baja California Sur. Some selected cultivars like ‘Blackheart’ and ‘Pastel Stripes’ are said to even have their origin at the Garden and are understood to be plant crosses emanating from a cutting of M. occidentalis that was gifted by the Garden to plantsman Ed Mercurio, which he subsequently planted, allowing for crosspollination by bees, resulting in deep, rich, and interesting flower colors.

Island mallow makes a wonderful, quick-growing, wind-breaking evergreen hedge, very well-suited for coastal gardens. We are happy to share several handsome specimens in our collection and encourage you to come to the Garden, where you can find it located in the Island View Section, as well as for purchase in our Garden Nursery. O

Gardener tip: If you are interested in growing island mallow in your garden, please note that mallows are very popular with deer and other ungulates, as well as rodents. Having adequate fencing protection is therefore advised.

Currin, K., Merritt, A., & Spriggs, P. (2023). The California Lavateras and Their Hybrids Pacific Horticulture. https://pacifichorticulture.org/articles/the-california-lavateras/ Hinsley, R. S. (2023). The Lavatera Pages: Californian Lavateras. Malvaceae Info. http://www.malvaceae.info/Genera/Lavatera/californian.html#assurgentiflora

northern island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora

southern island mallow (Malva

This map shows how ssp. assurgentiflora occurs on the four northern islands and San Nicolas Islands, while ssp. glabra only occurs on Santa Catalina Island and San Clemente Island. Each green dot represents locations of northern island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora ssp. assurgentiflora) and each yellow dot represents southern island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora ssp. glabra), recorded by either Santa Barbara Botanic Garden staff or specimen data from the Consortium of California Herbaria Portal 2 (CCH2). CCH2 is where digitized herbarium data from 48 institutions is stored, including data from the Garden.

ssp. assurgentiflora)

10 Ironwood

assurgentiflora ssp. glabra)

Welcome, Seniors

We invite those 60 and better to enjoy a day in the Garden — for free — thanks to our generous sponsor. Join us on one of our upcoming dates. Reservation are required.

August 16 | October 18 | December 13

Sponsored By

Grow With Us

Ironwood 11

12 Ironwood

The Unseen Ecology of Dirt: The Story of Mycorrhizae

By: Scot Pipkin, Director of Education and Engagement

“There’s a world going on underground.” —Tom Waits

If you spend time at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, you will hear many people talk about the “web of life.” It’s an elegant and instructive metaphor illustrating the strong but sometimes invisible connections between organisms. Disturb one strand and others will be affected. Lose many strands and the structure ceases to function.

As I write this article, the Garden is celebrating Bird Month, as a perfect example of the web of life. Not only do birds rely on plants for nesting, roosting, and direct food sources (fruits and seeds), they also rely heavily on the insects that are associated with plants. If we take the example of the Order Lepidopteran (butterflies and moths), we find that they represent up to 70% of a songbird’s diet (Piel, Tallamy, Narango, 2021). Most butterflies and moths rely on a limited set of larval host plants to survive. We can just look at the example of monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) and milkweed (Asclepias spp.) to get a sense of how the relationships function in the web of life. If we zoom more closely into this metaphorical web, we might notice something fascinating about the strands themselves. Like yarn or rope, these strands, which look like single, solid entities at our scale, actually consist of smaller fibers woven together, intertwined to create strength.

On any scale, the web of life metaphor reminds me to be aware of my connection to others, including those of the non-human (i.e., plant, animal, mineral) world. I have a friend who works as a hydrologist. They are quick to clarify that their interest and specialty are surface water, not groundwater hydrology. “Once it goes underground,” they say, “I pretend it doesn’t exist anymore. What happens down there is too complicated.” In many ways, I have felt a similar sense about ecology. The things that happen above ground, on terra firma, are within my realm of comprehension. Once we start asking questions about what’s happening beneath our feet, all bets are off. Don’t even get me started on marine or aquatic ecology. As I’ve gotten older and my curiosity more refined, the dark, often dusty (around here, anyway) world of soil ecology has remained mysterious; however, it has become less intimidating. Any sense of fear I’ve had has been replaced with allure.

author holding fruiting bodies of chanterelle fungus (Cantharellus sp.), an edible mycorrhizal fungus that associates with oaks (Quercus spp.) throughout California (Photo: Jessie Altstatt)

Establishing the Roots

Standing under the shade of an oak tree in California, say, a coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), blue oak (Quercus douglasii), valley oak (Quercus lobata), or canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis), one might feel the urge to dig down — beneath the layer of decaying leaves, twigs, and bark and into the earth. Across the threshold of duff and piercing the truly subterranean world, it might not take too long to encounter mighty roots mirroring a mighty canopy. Careful inspection of these woody threads would reveal that, like the metaphorical strands in the web of life, these structures are more than what they seem. In fact, these roots will begin to look a lot like the strands of the web of life previously described: intertwined lengths of living tissue exchanging energy and building resiliency. It’s one of the great and ancient symbiotic relationships in nature. It is an amazing partnership between plant and fungus.

Oaks (Quercus spp.) are not the only plants that benefit from this relationship with fungus. In fact, it is estimated that up to 90% of plants globally are involved in these relationships, where fungus in Class Mycorrhizae (etymologically speaking, “myco” refers to fungus and “rhizome” refers to root) works with plant roots. The ubiquitousness of mycorrhizal relationships with plants hints at their significance. In fact, research demonstrates that the presence of fungus in a plant’s roots greatly increases the plant’s ability to uptake water; absorb essential nutrients such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus (Simard, 2018); fight off pathogens (Duchesne, 1994; Linderman, 1994); and even reduce a plant’s susceptibility to herbivory (Koziol et al., 2018).

A closer study of mycorrhizal symbiosis is revealing fascinating insights into soil ecology. Researcher Suzanne Simard has spent decades studying such relationships in the temperate rainforests of western Canada, and what she has learned is awesome in the most literal sense. Based on Simard’s experiments, it is becoming clear that the mycorrhizal relationship with plants isn’t as simplistic as sharing resources. Mycorrhizal networks enable nutrient sharing between trees of multiple species and even facilitate communication within the forest. It appears that through the mycorrhizal network, trees can democratically allocate resources to each other and promote the growth of seedlings. Within the network,

Opposite: The

Ironwood 13

hubs of activity center around particular trees, often within a certain age class. These “Mother Trees” help dictate the distribution of resources within the network (Simard, 2018). Through these partnerships between Mother Trees and fungus, there is an ability to recognize both kin and individual neighbors (ibid). The health of the forest as we experience it is mediated in large part by what is happening below ground. A special shoutout goes to old growth habitats. Those are the realms of Mother Trees.

Such community-level implications aren’t limited to the ancient cedar and hemlock forests (Family Pinaceae) of the Pacific Northwest where Simard conducts her research. Here in California, researchers observed the transfer of nitrogen from gray pine (Pinus sabiniana) to nearby blue oaks (Southworth, 2013), suggesting that similar dynamics may be at play in the oak woodlands of California as they are in the forests of Canada. In fact, these mycorrhizal networks benefit a number of species in the plant community, including buckbrush (Ceanothus cuneatus), and other annual plants (He et al., 2006). Additional studies in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada reveal that dozens of mycorrhizal fungi can be associated with blue oaks and those communities can differ in significant ways from nearby interior live oak (Quercus wislizeni) associations (Morris et al., 2008). This study was only examining the diversity of ectomycorrhizae, or mycorrhizae whose hyphae (fungal equivalent to roots) do not penetrate the cell walls of the host roots. This class of mycorrhizae is particularly noteworthy because it includes chanterelles (Cantharellus spp.); agarics (Amanita spp.), including Amanita muscaria, one of the infamous “magic mushrooms”; and other common mushrooms of forests and woodlands. Mycorrhizae, therefore, are responsible for the health of our plant communities and a significant food source for humans the world over.

Biodiversity Loss and Recovery

Given the importance of mycorrhizae to plant communities, it stands to reason that we should be prioritizing the conservation of soil integrity in addition to saving the plants we care about. Conversely, we can also know that by saving native plants, even individuals in some cases, we are protecting the networks that support a healthy landscape on a broader scale. There is evidence that suggests soil disturbance ranging from tilling to grazing to development can significantly impact mycorrhizal fungi. In one study in coastal sage scrub communities in California, it appears that conversion to nonnative grasses has tilted the soil microbial balance to favor mycorrhizae that provide more benefit to the introduced plants.

This represents a possible competitive advantage for the invasive plants as they might be able to utilize their mycorrhizal advantage to outcompete native species (Brooks, et al., 2022).

The interconnected web of life is only one aspect of why biodiversity is so critical to ecological function on our planet. Living systems influence abiotic (nonliving) components of our world profoundly. In the steep terrain of Southern California, mycorrhizae work with plant roots to stem the pull of gravity and stabilize soils. Mycorrhizae help create soil aggregates through biochemical and biological processes (Rillig and Mummey, 2006). When living strands are broken through disturbance, soil is more easily eroded, leading to slumping, incised channels, and sometimes catastrophic slope failures. More than wildfire and flooding, human activities are a primary source of soil disturbance on our planet. The scale at which we convert native habitats for mining, forestry, agriculture, development, and transit is unparalleled. As a result, mycorrhizal communities are being negatively impacted by human activities across the globe (Xavier and Germida, 1999).

Your Home Garden Can Help

By now, it should be evident that mycorrhizal fungi are essential for supporting healthy habitats. In the face of massive disturbance and destructive practices, it might feel intimidating to think about what we as individuals can do to promote soil biodiversity and plant health. Fortunately, we have the potential to make real impacts in our local communities.

For those who have access to land, whether it be a yard or community site, what could be more beautiful than facilitating healthy soil interactions that could beget even more biodiversity? If you are a homeowner or caretaker of a property with land, consider this: for supporting mycorrhizal communities, any plant is better than bare soil or impervious concrete, a California-native plant is even better, and a locally adapted native plant is best. There is limited but potentially significant evidence that local genes might play a role in colonization by local mycorrhizal fungi (Van Geel, et al. 2021). Though rare, some local nurseries sell plants whose genetics they can confidently say come from nearby populations. But it all starts with native plants.

While it is possible to purchase mycorrhizal inoculants for installation in your own yard, it might not be as simple as acquiring a product and inoculating the earth. Fungi might be a little bit fickle, or at least adapted to more specific conditions. Some inoculants may be effective with some plants or soil conditions

14 Ironwood

but not colonize as vigorously in others. Manzanitas (Arctostaphylos spp.), for instance, have relationships with an entire group of mycorrhizal fungi (known as ericoid mycorrhizae), and some plants — like manzanita — benefit most from multiple mycorrhizal associations at once. Mycorrhizal communities may also change over time as a landscape or habitat matures. Inoculation can work for some species and might not be a bad idea in a landscape that has seen significant recent disturbance, but it may not be a necessary step toward healthy soil. Spores have been spreading for a billion years and fungi have found a way to colonize the various corners of this planet. There is hope that your small patch of soil could be the landing spot for a microscopic hitchhiker looking for a plant root to share energy with. Try to make that home welcoming.

In an age when climate change and threats to the web of life loom large over our environmental psyche, it’s easy to fall into a paralyzed sense of despair. This is a normal response. The problems are so big and we

as individuals have seemingly so little recourse, it’s easy to disassociate from the topic altogether. But I say, despair not! We have to fight for the things we love and what could be more beautiful than helping the next generation of Mother Trees get established?

Tips for Getting Started

Before prepping any ground or buying a tree from a nursery, it’s important to reconnect with nature. Fall back in love with the earth that sustains us and remind yourself that YOU are a strand in the web of life — reliant on other connections and capable of supporting a great load. Go outside and spark your curiosity. Walk around barefoot and connect with the earth. Carefully flip a decaying log and see what life lies just underneath the surface. Mycorrhizal fungi are an incredible, miraculous component of the world we inhabit, but theirs is just one story unfolding around us at all times. By cultivating your curiosity and establishing a connection to the natural world, you will be positioning yourself to be a better advocate for and steward of the web of life.

Ironwood 15

Which habitat has more mycorrhizae? Is it the oak (Quercus spp.) woodlands in the foreground or the agricultural fields in the distance? (Photo: Scot Pipkin)

Once you have reconnected with the natural world, there are actionable steps you can take to improve soil health and local ecology. Using natural mulch and home composting are great ways to contribute to soil biology and help create a good environment for organisms like mycorrhizal fungi to colonize. Bottomline, soils are home to an array of microbes, herbivores, hunters, decomposers, and other organisms that contribute to our local biodiversity. Planting native plants helps ensure that mycorrhizal networks can get established and local ecology has the opportunity to recolonize our lives.

Even if you don’t have access to a patch of earth to tend, there are significant steps you can take to advocate for native biodiversity and our local webs of life. I am consistently inspired by a friend who is a dedicated advocate for nature in our communities. They attend public meetings, provide public comment on development plans, serve on one of the local public tree advisory commissions, among other things. In turn, I’ve become activated to attend meetings, write comment letters, and use my voice to advocate for nature in our communities. What I’ve realized in the process is these are real policies with longstanding implications and precious few people are speaking up. Your voice can change the direction of local policy for decades and that should feel empowering. In fact, the Garden can be another “friend” encouraging you to get involved by signing petitions, writing letters,

and taking more action to support native plants and habitats.

So, go outside, commune with the earth, contribute to her well-being, plant native plants, and use your voice to let others know that we are all connected in this vast web. Like the spores of a chanterelle, your actions will multiply and intertwine with others to create something astonishing. O

Duchesne, L. C. (1994). Role of ectomycorrhizal fungi in biocontrol. Mycorrhizae and plant health (pp. 27-46). The American Phytopathological Society.

Piel, G., Tallamy, D. W., & Narango, D. L. (2021). Lepidoptera Host Records Accurately Predict Tree Use by Foraging Birds. Northeastern Naturalist, 28(4), 527-540. https://doi.org/10.1656/045.028.0410

Linderman, R. G. (1994). Role of VAM fungi in biocontrol. Mycorrhizae and plant health (pp. 1-26). The American Phytopathological Society.

Morris, M. H., Smith, M. E., Rizzo, D. M., Rejmánek, M., & Bledsoe, C. S. (2008). Contrasting ectomycorrhizal fungal communities on the roots of co-occurring oaks (Quercus spp.) in a California woodland. The New Phytologist, 178(1), 167-176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1469-8137.2007.02348.x

Pickett, B., Irvine, I. C., Arogyaswamy, K., Maltz, M. R., Shulman, H., & Aronson, E. L. (2022). Identifying and Remediating Soil Microbial Legacy Effects of Invasive Grasses for Restoring California Coastal Sage Scrub Ecosystems. Diversity, 14(12), 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14121095

Rillig, M. C., & Mummey, D. L. (2006). Mycorrhizas and soil structure. The New Phytologist, 171(1), 41-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01750.x

Simard, S. W. (2018). Mycorrhizal Networks Facilitate Tree Communication, Learning, and Memory. In F. Baluska, M. Gagliano & G. Witzany (eds.), Memory and Learning in Plants (pp. 191-213). https://boomwachtersgroningen.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/ Simard2018_Chapter_MycorrhizalNetworksFacilitateT-1.pdf

Southworth, D. (2013). Oaks and mycorrhizal fungi. Oak: Ecology, types and management (pp. 207-218). https://tinyurl.com/bdfybv28

Van Geel, M., Aavik, T., Ceulemans, T., Träger, S., Mergeay, J., Peeters, G., van Acker, K., Zobel, M., Koorem, K., & Honnay, O. (2021). The role of genetic diversity and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity in population recovery of the semi-natural grassland plant species Succisa pratensis. BMC ecology

https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12862-021-01928-0

and evolution, 21(1), 200.

16 Ironwood

Next time you see a mushroom, ask yourself, “What role does it play in the ecosystem?” (Photo: Scot Pipkin)

Thank You to Our Beer Garden Sponsors

FEATURED SPONSOR

FEATURED VENDORS

SPONSORS

All Heart Rentals

Arroyo Seco Construction

Landscape and Design

Balance Financial

Bibi Moezzi

Bite Me SB

BRIGHT Event Rentals

BrightView

Buddha Properties

Dan Crawford, Realtor

DiBenedetto Family

Edible Santa Barbara

Flowers & Associates, INC.

Forward Lateral

Helene Schneider

Hutton Parker Foundation

Jeffrey & Rebecca Berkus

VENDORS

Augie’s brewLAB

Convivo

Draughtsman Aleworks

Eating with Jo

Figueroa Mountain Brewing Co.

Firestone Walker Brewing Company

Island Brewing Company

La Paloma Cafe

Jump On The School Bus

Katalyst Public Relations

Knight Real Estate Group

Mission Wealth

Pondel Law

Randy Solakian Estates Group

Santa Barbara Adventure Company

Santa Barbara Life and Style

Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians

Sarah & Hayden Gower

Scale Microgrids

Schipper Construction

Sol Wave Water

The Spracher Family

Urgent Veterinary Care of Santa Barbara

Little Dom’s Seafood

Night Lizard Brewing Company

Oat Bakery

Sama Sama

T.W. Hollister

Tarantula Hill

Third Window Brewing

Topa Topa Brewing Co.

Tyger Tyger

Validation Ale

SBBotanicGarden.org

Ironwood 17

The Ecology Process: The Unusual Techniques Scientists Use To Study Ecosystems

By: Denise Knapp, Ph.D., Director of Conservation and Research

You’ve likely seen it in cartoons or on TV, if not in person: the geeky scientist collecting insects with a butterfly net, frantically swiping through the air for their prize then marveling at the tiny creature they have then trapped inside a jar. You may have chuckled at those strange people — you wouldn’t be alone — who are so fascinated by bugs that they want to collect one of everything. Trust me, it gets so much stranger.

Insects, together with other arthropods like spiders and centipedes, are the most species-rich animal group on the planet. They also do a wide variety of jobs, from the more picturesque act of pollinating flowers to the less fun feat of breaking down waste. So, it makes

sense that they are found in all kinds of places, with all kinds of behaviors — and that it takes all kinds of strange techniques to collect them when you want to understand our biological diversity and how to rebuild food webs from the bottom (native plants) up, like we scientists at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden do.

It starts with meeting them where they are at. Are they mostly flying around or hunkered down on (or in) a plant? Are they buried deep in the soil or in the plant litter? Are they active during the day or are they more of a nighttime kind of creature? Come with me as I lead you on a tour of just a few of the odd ways that entomologists (or ecologists, like those of us at the Garden) collect these critters.

Above: Winkler extractors hang below a string of old-school Christmas lights on Santa Rosa Island. (Photo: Denise Knapp, Ph.D.)

Above: Winkler extractors hang below a string of old-school Christmas lights on Santa Rosa Island. (Photo: Denise Knapp, Ph.D.)

18 Ironwood

Opposite: Casey Richart, Ph.D., uses the beat sheeting method on San Clemente Island within a woodland of island ironwood (Lyonothamnus floribundus) and island oak (Quercus tomentella). (Photo: Denise Knapp, Ph.D.)

Ironwood 19

Shake Them Loose

For those insects that feed on plants, you have to go to them. About half of all insects are herbivores, and about 70% of those are specialists that can only feed on a narrow range of related plants. Our favorite technique for getting those that like the green stuff is what’s called a beat-sheeting method, together with an aspirator (also called a pooter). We are literally beating the bugs off the plants and then sucking them up into a vial! First you place a white sheet stretched onto a frame beneath the plant of interest, and then you gently but vigorously shake the plant until the bugs fall off onto the sheet. Quickly you spring into action with the aspirator, with one tube that goes from the bug to the vial and another tube that goes from the vial into your mouth. When you suck on the tube, it draws the bug into the vial. Luckily, a layer of muslin or mesh keeps us from ingesting the hapless insect.

Flying Insects Love Color and Light

For flying insects, we typically trick the bugs into coming to us and then trap them there. Many dayflying insects are attracted to the color yellow, so we put out a yellow bowl with soapy water and after a while, voilà — bowl ’o’ bugs. The soap in the water breaks the surface tension so these tiny nimble creatures can’t crawl out. It’s sad, I know, but not harmful. An insect’s fine features help us identify them — the small patches of hairs or bristles, vein patterns on the wings, or the number of antennal segments — and we can’t see those details if they are moving.

After dark, black lights are great for night-flying insects like moths since most flying bugs are drawn to light. Black lights emit a type of UV light, which insects see but humans don’t. The UV lights also give off some heat, which helps to lure the insects. Then we diabolical scientists can pick off the bugs we most want with an aspirator.

20

Black lights draw many night-flying insects. (Photo: Denise Knapp, Ph.D.)

Ironwood

Creepy Crawlers Watch Out

We use a similar method to capture insects that crawl around on the ground. This version is called a pitfall trap, because — as the name implies — the insects fall into a pit. We have to be careful to bury the trap so that it doesn’t stick up above the soil; for tiny bugs this would act like a fence.

Collecting bugs from soil and plant litter is tricky. Sure, movement is a dead giveaway, but bugs are often quite tiny, which makes them difficult and time-consuming to separate from the small bits of soil and duff. Luckily, there is a smarter way! If you put soil and plant litter into a Winkler extractor device, with its internal mesh layers, and create heat using lights (see opposite photo), the bugs will separate themselves for you. They do this because they like to move downward and away from heat. Finally, jars of soapy water or ethanol at the bottom collect them for our research.

Preserving for Research

Once you’ve collected the insects, you need to preserve them for long-term scientific examination. For the bugs that we have collected dry and dispatched in the field, they must be pinned pronto, before they get brittle. But the bugs collected by way of soapy water still need to be preserved in ethanol so that they don’t decay. Once we bring these bonanzas

of bugs back to the lab, common household items help us finish the job. Bit by bit, we pour our bug stew into a plastic coffee filter and then use paintbrushes and forceps to transfer the bugs into vials of ethanol for later sorting, identification, and imaging.

For hairier insects like bees, the preservation is even more detailed than this. If you pin bees straight out of ethanol, they will end up looking permanently like wet dogs! Among other things, this makes the important identifying patterns on their bodies difficult to see. So, the bees need the diva treatment, via tea strainer and blow-dryer. First, you put a small clump of bees in the tea strainer — which acts like a little washing machine — and put them through a few wash-rinse cycles. Then it’s time for a blowout, which fluffs them up in a flash!

I may be in the minority in finding bugs always fascinating, often beautiful, and, many times, quite cute, but I hope that we can all appreciate that if we didn’t have them to pollinate our food, break down our waste, feed the food web, and maintain order in the ecosystem, we’d be in a world of trouble. You can help support them, and the many animals that depend on them, by building habitats with native plants. The diversity of life that you support will make our world more functional — and, if you’re asking me, even more fascinating. O

Ironwood 21

The San Clemente Island invertebrate surveys team: Jenny Hazlehurst Ph.D., Casey Richart, Ph.D., and Stephanie Calloway (Photo: Denise Knapp, Ph.D.)

The Bug Report: A Plant Is Worth a Thousand Bugs

By: The Invertebrate Ecology Conservation Team

By: The Invertebrate Ecology Conservation Team

A Survey of San Clemente Island’s Plant-associated Invertebrates

In 2019, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden conducted a survey of insects, spiders, and their invertebrate kin (collectively, “bugs”) on San Clemente Island. Of California’s eight Channel Islands, San Clemente is one of the most remote and least accessible, possessing a rich flora of rare and endemic plants. We collected bugs associated with these plants using an oldie-but-goodie entomological method called beatsheeting. Here’s a more than thorough description of the method: You place a sheet underneath a plant, hit the plant with a stick, and collect the bugs that fall onto the sheet.

Taxa Codependency

The island’s plants support bugs that feed, breed, and live on them, and the island’s bugs support plants through pollination and other services. To better understand these relationships, beat-sheeting was repeated at sites across San Clemente, and bugs were collected from a variety of plants in different habitats. The bug-plant co-occurrence data gleaned from this approach (i.e., what bugs were found on what plants) can ultimately help us better protect the Channel Islands’ distinct flora and fauna. For example, we collected specimens of a bark beetle new to science, Carphobius caterinoi, (Cognato & Smith) exclusively on island oaks (Quercus tomentella), suggesting the survival and reproduction of these beetles is dependent on the endemic oaks.

Divide and Curate

We found a lot of bugs, looked closely at a lot of bugs, and photographed a lot of bugs, many recorded on San Clemente Island for the first time (Phillips et al., 2023). Such intensive bug work can transform anyone into a connoisseur of fine insects (e.g., bees and butterflies), or even an enthusiast of Two-Buck Chuck creepy-crawlies (e.g., ants and cockroaches). Without exception, the Garden staff and volunteers who helped on the project became bug ambassadors, each developing an affinity for certain groups of invertebrates. Kylie Etter became a wasp whisperer, José Flores earned his bad beetle-boy badge, Jordan Sanderson took a long trip on the thrips train (last stop: more thrips), Laiken Warner and I gazed into the

eyes of arachnids, and Denise Knapp, Ph.D., swarmed the flies.

In the gallery that follows, we each share some of our favorite bugs from the survey and describe one of the tools we used to identify, curate, or photograph

Team using the beat-sheeting method in the field (Photo: Denise Knapp, Ph.D.)

22 Ironwood

said bugs. The photos represent just a few of the approximately 55,000 individuals we collected, belonging to 695 morphospecies (morphospecies are hypothesized species based on morphological characteristics), 201 families, and 33 orders. You can view more photos on the survey’s iNaturalist page,

a publicly accessible digital collection of specimens (“2019 SBBG Terrestrial Inverts of San Clemente Island” project at iNaturalist.org). If you’d like to get involved with similar projects at the Garden, contact me about bug volunteer opportunities (zphillips@ SBBotanicGarden.org).

Ironwood 23

Take a look at some of the 48 plant taxa on which we collected bugs during the survey, including rare and endemic Channel Island species and subspecies.

All plant photos provided by Casey Richart, Ph.D.

San Miguel Island milkvetch (Astragalus miguelensis)

Island mallow (Deinandra clementina)

San Clemente Island paintbrush (Castilleja grisea) Coastal pricklypear (Opuntia littoralis)

San Clemente Island buckwheat (Eriogonum giganteum var. formosum)

Island false bindweed (Calystegia macrostegia)

San Clemente Island evening-primrose (Camissoniopsis guadalupensis ssp. clementina) 24 Ironwood

San Miguel Island milkvetch (Astragalus miguelensis)

Island mallow (Deinandra clementina)

San Clemente Island paintbrush (Castilleja grisea) Coastal pricklypear (Opuntia littoralis)

San Clemente Island buckwheat (Eriogonum giganteum var. formosum)

Island false bindweed (Calystegia macrostegia)

San Clemente Island evening-primrose (Camissoniopsis guadalupensis ssp. clementina) 24 Ironwood

San Clemente Island bird’s-foot trefoil (Acmispon argophyllus var. adsurgens)

California golden violet (Viola pedunculata)

Golden-spined cereus (Bergerocactus emoryi)

San Clemente Island brodiaea (Brodiaea kinkiensis)

San Clemente Island bird’s-foot trefoil (Acmispon argophyllus var. adsurgens)

California golden violet (Viola pedunculata)

Golden-spined cereus (Bergerocactus emoryi)

San Clemente Island brodiaea (Brodiaea kinkiensis)

Ironwood 25

San Clemente Island larkspur (Delphinium variegatum ssp. kinkiense)

Kylie Etter Conservation Technician

Metaphycus wasp (Order Hymenoptera) specimen collected from coyote bush (Baccharis pilularis)

Most of the world’s wasp diversity is made up of tiny parasitoid wasps, like this one (Metaphycus sp.). Parasitoid wasps grow on or inside their hosts as juveniles and they must kill their hosts to complete their lifecycle. (This is what distinguishes parasitoids from parasites, which don’t have to kill their hosts). Due to the hyper-diversity and tiny size of parasitoid wasps, they can be difficult to identify. I was only able to identify this specimen to family (Encyrtidae), but after posting these photos on BugGuide.net, a wasp expert was able to identify it to genus. He also noted that this might be an undescribed species, which means it has not been formally described and named.

Phygadeuontini wasp (Order Hymenoptera) specimen collected from island buckwheat (Eriogonum grande var. grande)

Can you spot the wasp among the acrobat ants (Crematogaster sp.) in this picture? I don’t know why she is pretending to be an ant, but I am sure it’s to her benefit!

The wasp is a parasitoid wasp in the Family Ichneumonidae. Compared to the ants, it has long antenna with numerous segments, a smaller head, bigger eyes, and a long ovipositor (a long, specialized organ used to deposit eggs) extending out from the end of its abdomen.

Urbane Digger bee (Order Hymenoptera) specimen collected in chaparral woodland

The Urbane Digger bee (Anthophora urbana) can be found on the mainland, but this subspecies, Anthophora urbana ssp. clementina, is an island endemic. The island subspecies has rusty red colored hair, while the mainland one has more blond hair. Anthophora urbana ssp. clementina visits some of the island’s rare plants such as San Miguel Island milkvetch (Astragalus miguelensis), leafy desert dandelion (Malacothrix foliosa ssp. foliosa), and San Clemente Island bush mallow (Malacothamnus clementinus).

Mason bee (Order Hymenoptera) specimen collected on the ground

We collected 15 specimens of Osmia aglaia from the island, a species previously not recorded as being on San Clemente. It’s important to do insect surveys consistently to track population numbers, understand community structure, and record new species either recently introduced to the island or that have been missed in past efforts.

Paintbrush

The paintbrush is my favorite all-around go-to tool while doing insect sorting, identification, and photographing. It can gently separate insects from one side to the other in a petri dish of ethanol, pick up insects and move them from vial to vial, and brush off any dirt or dust clinging onto pinned specimens interfering with getting the perfect picture.

26 Ironwood

Clockwise from upper left: Kylie Etter in the field on Santa Cruz Island, Metaphycus wasp (Photo: Alex Jimenez), Kylie's favorite tool (Hand model: Zach Phillips, Ph.D. Photo: Kylie Etter), two photos of the Phygadeuontini wasp (Photo: Kylie Etter/Alex Jimenez), Mason bee (Photo: Kylie Etter), and Urbane Digger bee (Photo: Kylie Etter)

Ironwood 27

José Flores Conservation Technician

California ladybeetle (Order Coleoptera) photographed on San Clemente Island buckwheat (Eriogonum giganteum var. formosum)

The California ladybeetle (Coccinella californica) is a species of ladybeetle that exists along the coast from Baja California, Mexico, to southern Alaska. They’re easy to identify from their spotless forewings (called “elytra”), and a dark band running vertically across their elytra. Overall, ladybeetles are a nice guest to have around your home garden. They may not look like voracious predators to us, but they eat a lot of aphids, including the pesty aphids that can infest garden plants.

Johnson’s ladybeetle (Order Coleoptera) photographed on golden yarrow (Eriophyllum confertiflorum)

Johnson’s ladybeetle (Coccinella californica form johnsoni) is a form of ladybeetle that exists on islands along the western United States and Canada, including the Channel Islands. It has five large spots on each forewing and one spot being shared between the forewings, giving it a total of 11 spots. Sometimes the two spots in the back appear to be coalescing into one giant spot.

Kidney-spotted fairy ladybeetle (Order Coleoptera) specimen collected from coyote bush (Baccharis pilularis)

Lady beetles (Family Coccinellidae) are diverse. This kidney-spotted fairy ladybeetle (Psyllobora renifer) has the same general shape as the other ladybeetles collected on San Clemente Island, but it exhibits a distinct color pattern on its hardened forewings.

Ladybeetle larva (Order Coleoptera) specimen collected from island morning glory (Calystegia macrostegia ssp. amplissima)

Before a ladybeetle (Family Coccinellidae) matures into an adult and develops its wings, it looks like this. Like adult ladybeetles, the larvae feed voraciously on aphids that feed on plants. Insect larvae are generally more difficult to identify than adults, and the vast majority of insect identification keys and guides are based on adult features, not larval ones. This is one of the reasons we generally didn’t include larvae in our survey.

BugGuide.net

We post images of some of our specimens on iNaturalist.org, a well-known nature website and app used to share images and information about all kinds of animals and plants, and on BugGuide.net, a website used in a similar fashion but exclusively for “insects, spiders, and their kin.” BugGuide has been around since 2003, and it is where a lot of experts have congregated to help identify these invertebrates. The website also serves as a great learning tool as each unique species, genus, etc., has its own page that is curated by frequent users where they can add information such as identification tips, species ranges, and a list of print and internet references, to name a few. For our San Clemente Island invertebrate project, we posted on BugGuide only if iNaturalist did not assign an ID to a specimen’s taxonomic family within a week. Like iNaturalist, identification on BugGuide is all based on volunteer time, so we do not expect an immediate response, but we always get excited when our tougher-to-identify specimens are identified.

28 Ironwood

Clockwise from upper left: José Flores in the field capturing his latest specimen, the California ladybeetle (Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.), the Kidney-spotted fairy ladybeetle (Photos: José Flores), ladybeetle larva (Photos: Helen Noroian), José's favorite tool, and the Johnson's ladybeetle (Photo: Casey Richart, Ph.D.)

Ironwood 29

Jordan Sanderson Volunteer

Thrips (Order Thysanoptera) specimen collected on island buckwheat (Eriogonum grande var. grande)

Over half of the insects that were collected on San Clemente Island are thrips (Order Thysanoptera), which have close associations with plants. They’re hard to see with the naked eye, especially their feathered wings and the hairs all over their body.

Thrips (Order Thysanoptera) specimen collected from bush sunflower (Encelia californica)

Thrips (Order Thysanoptera) specimen collected on blue dicks (Dipterostemon capitatus)

Springtail (Order Collembola) specimen collected on California sagebrush (Artemisia californica)

Like thrips, springtails (Order Collembola) are a ubiquitous but often overlooked group of tiny animals. Springtails are closely related to insects, but they don’t have jointed appendages like insects do.

Springtail (Order Collembola) specimen collected on common fiddleneck (Amsinckia menziesii var. intermedia)

Springtail (Order Collembola) specimen collected on California sagebrush (Artemisia californica)

Dissecting scope

Sorting through all the insects in this project would have been impossible without the help of a dissecting microscope. This scope allows 3D views of teeny tiny objects and allows invisible details to be seen as clear as day. It also allowed us to orient bugs properly before placing them under the microscope camera and photographing them. Clockwise from top left: Jordan Sanderson in the Garden, thrips collected on island buckwheat (Photo: Helen Noroian), springtail collected from California sagebrush (Photo: Alex Jimenez), springtail collected from fiddleneck (Photo: José Flores), José working

30 Ironwood

with Jordan's favorite tool (Photo: Kylie Etter), another springtail collected from California sagebrush (Photo: José Flores), thrips collected on blue dicks (Photo: Helen Noroian), and thrips collected from bush sunflower (Photo: Helen Noroian)

Ironwood 31

Leafhopper (Order Hemiptera), with a parasitoid wasp attached (Order Hymenoptera) — specimen collected on island tarplant (Deinandra clementina)

This leafhopper (Family Cicadellidae) should choose its friends more carefully. The dark blob attached to its side is a parasitoid wasp larva. At this stage, both the leafhopper and wasp are juveniles. Eventually, the wasp will emerge as an adult, mate, and if she’s female, find more leafhoppers to deposit her eggs in.

Phidippus jumping spider (Order Araneae) specimen collected from coastal prickly pear (Opuntia littoralis)

Have you ever seen a spider sparkle? This is the distinctive face of a jumping spider (Family Salticidae), and the sparkle is coming from its chelicerae, or jaws. Jumping spiders don’t capture prey in webs. Instead, they actively track them down, and their two large, forward-facing central eyes help them hunt.

Mecaphesa crab spider (Order Araneae) specimen collected from San Clemente Island paintbrush (Castilleja grisea)

Here’s a peek into the arachnid cardiovascular system. Spiders have hearts too, you know! This crab spider (Family Thomisidae) was collected from the endemic plant San Clemente Island paintbrush (Castilleja grisea), where it may have been waiting to pounce on visiting pollinators.

Hand sanitizer

Hand sanitizer is the unsung hero of the invertebrate imaging world. The humble sanitizer holds bugs in position while taking a photo with the microscope. And when you need to move the bug to get another angle, it’s easy to do. For the project, we typically took at least three photos of each specimen: one from above (dorsal), one from below (ventral), and one from the left side (lateral) of the bug.

Laiken Warner Volunteer

32 Ironwood

Clockwise from top left: Laiken Warner along the coast of Santa Barbara, California, two images of parasitoid wasp larva attached to a leafhopper (Photos: Zach Phillips, Ph.D.), Laiken's favorite tool (Photo: Kylie Etter), two images of the Mecaphesa crab spider (Photo: Laiken Warner), and the face of the Phidippus jumping spider (Photo: Laiken Warner)

Ironwood 33

Zach Phillips, Ph.D.

Terrestrial Invertebrate Conservation Ecologist

Metepeira orbweaver spider (Order Araneae) specimen collected on San Clemente Island hazardia (Hazardia cana)

Spiders are astute botanists, and they use their ancient knowledge of plants to hide and hunt more effectively. They camouflage themselves against flowers, anchor webs to stems and branches, and hop around vegetation seeking prey. This fuzzy Metepeira spider is in the orbweaver family (Araneidae), a group that decorates San Clemente’s plants with silken traps.

Jumping spider (Order Araneae) specimen collected on coyote bush (Baccharis pilularis)

Jumping spiders (Family Salticidae) get a lot of media attention because they’re adorable — and they know it. As if this spider’s head wasn’t big enough already, you can see an enlarged copy of this photo on a wall in the Pritzlaff Conservation Center Gallery at the Garden.

Ghost spider (Order Araneae) specimen collected from Blair’s wirelettuce (Munzothamnus blairii)

Some of the spiders we collected on San Clemente feed directly on plants. In addition to eating bugs, ghost spiders (Family Anyphaenidae) drink nectar from flowers to help fuel their active lifestyle.

Stilt bug (Order Hemiptera) specimen collected from island tarplant (Deinandra clementina)

What a bug. Its long legs are characteristic of the family it belongs to, the stilt bugs (Berytidae). It was collected from island tarplant, where it was likely using its straw-like mouthparts to suck some of the plant's juices, or scavenging other insects stuck to the plant's surface. The stilt bug’s spines and long legs help it avoid a similar fate, enabling freer movement through a plant’s sticky and clingy hairs.

Leafhopper (Order Hemiptera) specimen collected from San Clemente Island buckwheat (Eriogonum giganteum var. formosum)

This leafhopper (Family Cicadellidae) likely represents a new species to science. If she seems bland, it’s not her fault. Blame us. Her natural colors have been washed away by the ethanol in which she was stored. She uses the long, bladelike ovipositor at the end of her abdomen to lay eggs inside of plants. We don't know which plants, but our survey results suggest a few candidates, including San Clemente Island buckwheat.

Coffee

We need to talk. Yes, it’s serious. I don’t ever want to see your ugly mug again. Sure, I remember the good times. We’ll always have the jitterbug, you and I — we danced like it was nobody’s business! I held the bugs, and you made them jitter. But that doesn’t change a thing. The project is over, and I need to sleep. You’re out; chamomile is in. I’m telling you SCRAM, bub! You may not be single origin, but you’re single now, got it? I don’t care where you go, just lose my number and stop sending me latte art. Wait, don’t leave … maybe just one more sip.

34 Ironwood

Clockwise from top left: Zach Phillips, Ph.D. on the University of California, Santa Barbara campus, Metepeira orbweaver spider (Photo: Laiken Warner), jumping spider (Photo: Laiken Warner), leafhopper (Photo: Zach Phillips, Ph.D.), ghost spider (Photo: Alex Jimenez), two images of the stilt bug (Photos: Zach Phillips, Ph.D.), and a brokenhearted mug of coffee (Photo: Zach Phillips, Ph.D.)

Ironwood 35

Denise Knapp, Ph.D. Director of Conservation and Research

Bee Fly (Order Diptera) specimen collected from California golden violet (Viola pedunculata)

Bee flies (Family Bombyliidae) are the reason I went back to graduate school. While working as a plant ecologist on Catalina Island, I would watch them and wonder what they were. There I was, trying to protect an array of very rare plants, and I didn’t know who their pollinators were. Bee flies are not only adorable and effective at pollinating while they stick their long mouthparts into a deep-throated flower, but they also have a cool edginess: their larvae are parasitoids of other insects, especially bees. This one (Bombylius major) was collected from California golden violet (Viola pedunculata).

Robber fly (Order Diptera) specimen collected on a rock

Everything about this robber fly (Family Asilidae) says “predator.” The piercing mouthparts, huge eyes, and copious strong bristles are most obvious. It takes more observation, though, to see these venomous, athletic flies catching and sedating their prey, and then sucking out the contents of their bodies, all while on the wing. They have a long mustache called a mystax that protects them from their flailing victims.

Cactus fly (Order Diptera) specimen collected on island false bindweed (Calystegia macrostegia)

One reason I love flies is that they do so many jobs that benefit ecosystems and people. They pollinate flowers, help control pest populations, and, among other things, act as saprophages that break down dead and decaying matter. The cactus fly pictured here (Odontoloxozus longicornis) is a saprophage, and commonly feeds and breeds in rotting cactus. Although there is only a single species of cactus fly recorded from the United States, regional populations exhibit distinct genetic variation, including those on the Channel Islands.

Fly books

The most important tool for me when identifying flies is a good dichotomous key, with descriptions and illustrations that help me decide if I got it right or not. “Flies: The Natural History and Diversity of Diptera” by Stephen A. Marshall has a wonderful, user-friendly key with drawings of important features, along with excellent natural history information and photographs. “The Manual of Nearctic Diptera” volumes, authored by numerous experts, have many illustrations of the different groups and important features like wing venation, bristle patterns, and facial features.

O

Cognato, A. I., & Smith, S. M. Taxonomic review of Carphobius Blackman, 1943 (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and a new species from San Clemente Island, California, U.S.A. The Coleopterists Bulletin. (In review) Phillips, Z. I., Flores, J. M., Etter, K. J., Lee, C., Calloway, S. M., Searcy, A. J., Sanderson, J., Warner, L., Zhang, D., Trujillo, S. H., Makler, L. C., Zendejas, S., Noroian, H. M., Martín, A. J., Cusser, S. J., & Knapp, D. A. (2023). San Clemente Island Terrestrial Invertebrate Survey: Guiding Biodiversity Inventory, Rare Plant Conservation, and Habitat Restoration. Report prepared for U.S. Navy by Santa Barbara Botanic Garden.

36 Ironwood

Clockwise from top left: Denise Knapp, Ph.D., enjoying her home native garden, two images of the bee fly (Photo: Alex Jimenez), two images of the cactus fly (Photo: Alex Jimenez), two images of the robber fly (Photo: Alex Jimenez), and Denise’s favorite tool (Photo: Denise Knapp, Ph.D.)

Ironwood 37

38 Ironwood

Why Our Living Collection Matters

By: Christina Varnava, Living Collection Curator

The towering bigcone Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga macrocarpa) in the Manzanita Section. The colorful irises (Iris spp.) surrounding the Meadow Section. The elusive California peony (Paeonia californica) on the Porter Trail. The appearance of these plants is very different, but they are all part of the Living Collection at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden. The Living Collection is one of the Garden’s three American Alliance of Museums accredited collections, along with the Blaksley Library and the Clifton Smith Herbarium. But what exactly is a living collection?

A Record of Every Plant

Living collections are distinguished from ordinary gardens by the practice of keeping and maintaining detailed records on their specimens. These accession records include information about where and when a plant was collected, which is also known as its provenance. Provenance data is critical, since without it, there is no way to trace the origins of a plant.

A great example of the value of provenance is the accession record for our great yellow pond-lily (Nuphar polysepala), which is located in the Arroyo Section. The great yellow pond-lily is not a rare species; it is found in wetlands throughout western North America and is quite common in Northern California. However, it no longer grows in Southern California. When our specimen in the Arroyo bloomed last year for the first time in years, I looked at the accession record for additional information that we could share with our visitors. What I found surprised me. Our specimen was collected in 1956 from Santa Barbara County from a place that was once a wetland but is now a golf course. Now that its habitat is gone, this plant is no longer found in the wild there — or in other places it historically existed in Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties. Our specimen, therefore, represents a part of the genetic diversity of this species that would have otherwise been lost. It may have a part to play in helping with restoration efforts someday in the future, but in the meantime, it will be cared for here at the Garden to ensure its continued existence (figure 1).

In addition to harboring genetic diversity, living collections are used in a variety of ways. Researchers

have used the plants in our Living Collection for projects on pollination biology, documenting hidden patterns of UV colors on flowers (figure 2), understanding gall ecology, measuring live fuel moisture to learn more about how fires spread, and more. Living collections are excellent tools for research, since they can house a broad array of species in a relatively small space. Plants in a collection also respond to stimuli from their environment in ways similar to how they would in the wild.

Conserving California’s Biodiversity