Almost a year ago I received a phone call out of the blue from Rob Griffiths, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Britain (CPB). I had worked with Rob as part of a team organising the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Cable Street back in 2011. “We need to start thinking and planning for the 80th,” he said.

I knew this 80th anniversary would be significant for a simple but sad reason: among the tens of thousands who took to the streets in 1936 to repel a fascist invasion of the overwhelmingly Jewish districts of the East End, were some incredibly brave teenagers. Even the youngest of those teenagers would now be in their 90s. At all the previous five- or ten-yearly commemorations, battle veterans shared their experiences with younger generations of activists. This might be the last one where we will hear those voices. I honestly don’t know whether we could organise future commemoration without the participants and witnesses of the actual event. I was determined that this one – the 80th – would be a large, vibrant and memorable event.

And it was. People I’ve never met before described it afterwards as “amazing’, “inspiring” and “beautiful”, but the fact that it happened at all was the result of winning a battle we didn’t know we would have to fight.

Resurrecting the Core

Rob and I couldn’t do it alone. We began contacting the group that had helped to organise the 75th anniversary commemoration. Some had moved away from London or were bogged down in other issues, but we quickly resurrected a core group: myself from the Jewish Socialists’ group; Rob and a few comrades from the CPB; representatives from local secular Bengali community organisations; Gerry Gable from the anti-fascist magazine, Searchlight; and the small band of comrades – the Cable Street Group – who had ensured the continuity of commemorations since 1986. An initial planning meeting for Cable Street 80 took place in the café at the idea Store (library) in Whitechapel in December 2015, which Rob and I co-chaired. A skeleton plan emerged – a march and rally, and a set of cultural events centred on an exhibition that the Cable Street Group had prepared for the 75th.

Last time round, the trade union movement, especially with the towering presence of RMT General Secretary, Bob Crow, and comrades at UNITE, supported us well. We set up a meeting at UNITE’s central London office, aiming to get unions on board again.

We created a pattern of alternating meetings. Our East End-based gatherings would develop the cultural programme. These mostly took place at what became our hub: the UNITE Community space, located in the basement of 236 Cable Street, the Old St George’s Town Hall whose outside wall is decorated with the phenomenal Cable Street Mural, a constant, stirring reminder of what we were commemorating and why. Our planning meetings focusing on the march and rally continued at UNITE’s central offices

Somewhere within these tentative first steps, Rob Griffiths suggested that we needed a convenor, and I was thrust into the role – not unwillingly, but privately daunted by the responsibility!

Announcing plans

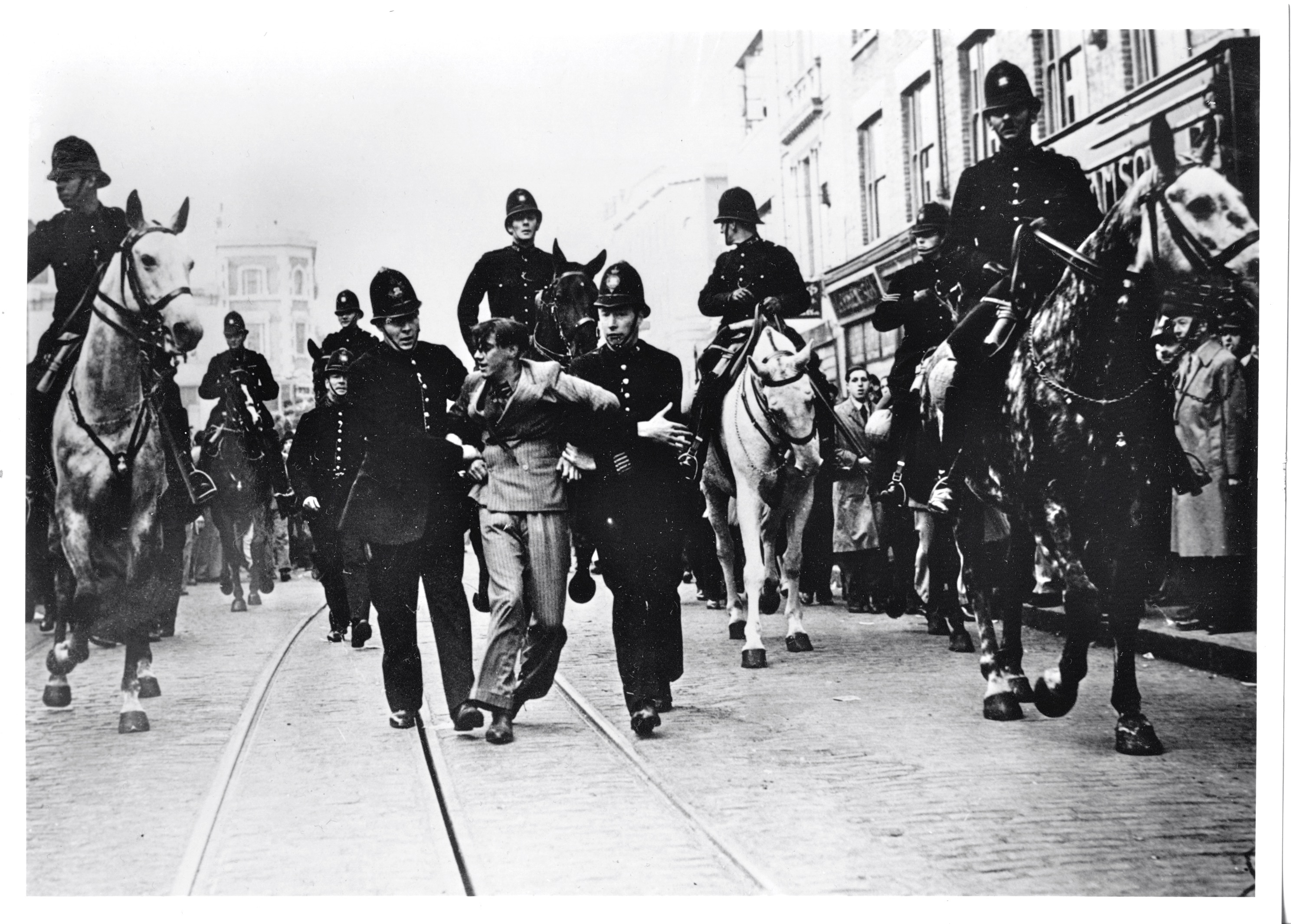

Back in 1936, when Sir Oswald Mosley, 6th Baron of Ancoats, wanted to march through the East End, he merely had to announce it, and a friendly Home Secretary, John Simon, promptly obliged. When nearly 100,000 local residents, petitioned Simon to bar this march on the grounds that it would further inflame local tensions in a period when East End Jews were already suffering fascist violence, Simon recalled important rights and freedoms from our unwritten constitution – the rights to intimidate, threaten, abuse and attack. OK, he dressed them up as “free speech” and “freedom of movement” but it was clear in this context what they meant. The right of East Enders to live free from fear didn’t enter into the Home Secretary’s reckoning. He sent 7,000 police to support Mosley’s venture, and we all know how that worked out.

We made our announcement in February 2016, choosing the nearest weekend date to October 4th that didn’t clash with a Jewish holiday or a time when many likely supporters would be out of London hurling insults at Tories starting their conference. We settled on 9th October. A generous offer of free design and printing of our initial leaflet came our way, and we leafleted the large anti-racist demo called in March so as to claim the date and announce our assembly point: 12 noon, Altab Ali Park, Whitechapel Road, to march to Cable Street.

We didn’t need permission from the Home Secretary, but we did need permissions and cooperation from the local council. You might expect that the London Borough of Tower Hamlets would welcome the enthusiasm of a group of people committing their spare time, experience and expertise to organising a huge event to mark such a proud moment in the borough’s local history. An initial meeting of three members of our ad hoc committee with two councillors and an officer from the council’s Community Events team seemed promising. From here on, we would be meeting with council officers, initially at a site meeting, and later at a multi-agency indoor meeting at the Events team’s premises at the Brady Arts & Community Centre – appropriately a former boys’ club in the heart of the old Jewish East End. They did warn us that this would be the first of several meetings. They weren’t kidding.

In 1936, the barriers that stopped Oswald Mosley were tens of thousands of East Enders physically blocking his path at Gardiner’s Corner and a set of elaborate barricades in and around Cable Street. The barriers we faced were bureaucracy gone mad, meetings where we were bombarded with unfamiliar sets of initials and unexplained jargon, being instructed to act on decisions at those meetings without the officers producing the promised minutes or explanatory notes. We were admonished for giving out leaflets advertising an assembly point and time, without getting permission first to use that space, and, until we had that permission, were effectively banned from doing more than the vaguest publicity for the event (9th October, somewhere in the East End…). So our leaflets were mothballed for the time being.

Despite the officers’ claims they were trying to support us through the correct procedures, it felt as if they were putting every possible obstacle in our way. For the Risk Assessment, we were asked to envisage and show how we would respond all kinds of unlikely hypothetical scenarios. One of our committee members, Joel, did many hours of amazing work on this largely irrelevant detail.

Kafka’s East End

Just as the police in 1936, having dislodged the first barricade in Cable Street were dejected when they found another (and another), so, every time we thought we had leapt the final hurdles, new obstacles appeared. The most bizarre moment, less than 24 hours before a crucial meeting where we thought we were near the end of this completely Kafkaesque process, an email arrived with a “few” other points to consider before the meeting. The list started: a), b), c)… and ended with this letter: y). At the very last minute, they had actually given us 25 further points to address.

All this time we knew we needed to build maximum support for such an important event but felt we had to do so blindfolded and with our hands tied behind our backs. How could we mobilise if we couldn’t even tell our public were the event would assemble?

We proposed a route early on that would use some main streets, as well as passing key points of political significance from 1936 and take us into the heart of the local community whose, support and engagement we were seeking. It was made clear that this would cost us thousands of pounds in enforcing road closures. The final route – a compromise we could live with – was only confirmed by council officers, TFL and the police a month before the march. This agreement owed more to one police inspector with a “can do” attitude than to the council officers whose job was to facilitate and support the event.

It involved crossing one major road. Council officers and the police tried to force us to employ professional “CSAS -trained” stewards for this, telling us they were the only ones who had the legal right to force vehicles to halt. We held firm in rejecting this. We were not going to employ expensive, private stewards but wanted the march to be stewarded by people committed to the event, recruited on a voluntary basis from the trade union movement and local community organisations. We won that battle.

Whose Parks?

In the face of these obstacles, there were voices advising us to simply ignore the bureaucracy and just do it. This might have worked if we had simply wanted to protest on the streets and risk a chaotic and fraught situation with the police. But we had a responsibility to all our participants – including very elderly people and families of those who had been there in 1936, and those less able to cope with uncertain street arrangements. Besides, we had chosen the starting and finishing points for their special significance to antifascists. And in any case, these are our parks.

We chose to assemble in Altab Ali Park because it is named in memory of a young Bengali clothing worker murdered by racists in 1978. At that time, the Bengali community was facing a rerun with the National Front of the battles Jews endured in the 1930s with Mosley’s Blackshirts. We chose St George’s Gardens because this is also the site of the Cable Street Mural – the most powerful memorial of the events of ’36. We would not compromise on our right to use those spaces.

At a meeting with council officers in late August we squeezed out of them permission to advertise the assembly and destination points on two crucial publicity tools we had now established: a Cable Street 80 website set up by Dave, a CPB member; and a Facebook event page set up by John, a UNITE member in Yorkshire, enthusiastic about the Cable Street commemorative event. Even then, we had to publish a proviso, adding “subject to confirmation by the London Borough of Tower Hamlets”.

The last three weeks before the event were particularly frantic. We were asked to attend more meetings, at which a tsunami of extra demands were made by the council officers – just 47 (yes 47!) new paperwork points to clarify nine days before the event! Meanwhile, we received a threat that a fascist organisation would disrupt the day, which our stewards had to prepare for. The paperwork continued to multiply in the run-up to a final planning meeting on Thursday 6th October. I was running on empty by now. I had contracted flu in mid-September which hung around in the form of a heavy cough and cold. I turned up for that final meeting late and exhausted, but with a secret weapon up my sleeve.

As we experienced more and more bureaucracy, and increasingly ridiculous petty demands, we appraised a couple of Tower Hamlets councillors of what we now concluded was obstructive behaviour by the officers. One of these councillors was Asma Begum, whom we met at that first meeting with the Council back in April. We were also keeping the Tower Hamlets Mayor’s office informed, so they knew that we were experiencing problems. Mayor Biggs was one of our invited speakers, alongside other significant local political figures – Rushanara Ali MP and Unmesh Desai the GLA representative for City and East London.

In that final meeting I was there alone with three council officers, one transport representative, and the Police Inspector who had helped to finalise our route. We had met every reasonable demand for paperwork and assurances, and, to my mind, many unreasonable and irrelevant ones, too. I felt physically drained. My head was at exploding point. In light of their behaviour towards us over the previous weeks, I was worried that the council officers would pull some final stunt to undermine the event, so, the night before, without informing the people who would be in the room, I had informed two councillors and the mayor’s office of this meeting and suggested they might wish to attend. Cllr Begum had another meeting at the same time but said she would try to get to ours afterwards.

A knock at the door

As far as I was concerned we had delivered everything asked of us. This meeting should have rubber-stamped our final plans; the officers might even have thanked our committee for the incredible amount of tough, unpaid work, at all kinds of unsocial hours, that we had put in to meet all their bureaucratic demands. But, no. They seemed to be more concerned with trying to find holes in our plans.

The meeting got increasingly tense. I didn’t hide my frustration. Then there was a knock at the door, and in came Cllr Begum. “Hi Asma,” I said, smiling. It was a beautiful moment watching the reaction on the faces around the room as it dawned on them that they were now the ones being scrutinised. The rest of the meeting was much more pleasant and relaxed for me as the officers tried to impress Cllr Begum with their diligence and support for this significant event! (In return I fixed up a selfie for Cllr Begum with Jeremy Corbyn on the platform on the Sunday.)

At last we had the upper hand. I still had to produce some final paperwork by 9am on the Friday, then attend a site meeting on Friday afternoon for both sides to sign the contract for use of the parks, and get a set of keys for the St George’s Park gate so that the staging, equipment and portaloos could be delivered. Cllr Begum asked me, in front of the officers, if I felt i could meet that 9am deadline. I said I wasn’t sure I could. With my cold I would be too tired to work in the evening, and would have to get up long before sunrise to do it. An extra hour was magically granted. I confirmed that I could do it by 10am.

On the Friday before the Sunday of the event, I got up at 5.45 (one of many such early starts over the previous few weeks) to complete the paperwork. At 9.52am I sent the final, final, final paperwork. At 11.54 I received an email: “Thank you for your updated plans which have taken on board the outcome of the meeting yesterday. We will issue your contract this afternoon at our site meeting.” At fucking last!

We fixed the time for the afternoon meeting. I breathed a sigh of relief, ran a bath and my mood improved. But there was a sting in the tail. Just before I got in the bath the phone rang and more emails arrived. There was a query about the staging arrangements in St George’s Gardens, even though the council officers had full details of this four days earlier. Apparently we suddenly needed a “Section 30 Building Control Order” for permission to erect the staging, at a cost of £180 which had to be paid immediately. We had sufficient backing from the trade unions to cover the fee – but I then had to spend 90 minutes of non-stop emails and phone calls trying to get a whole new piece of bureaucracy sorted out there and then. What was the anchorage for the stage? Fuck knows. What would happen in a freak storm? Fuck knows. (The weather forecast for Sunday was sunny and calm.) I did the best I could, then jumped in the bath, jumped out, ran to the meeting to sign the contracts, and between visiting the sites, I jumped the final bureaucratic hurdle and paid the £180 by phone that confirmed the arrangement. A lot of jumping.

The weekend was now upon us. On the Saturday afternoon, at Watney Street Idea Store, where the Cable Street exhibition was on display, there was a fantastic meeting with three women who were witnesses and participants in October 1936. I had tickets that night for the jewdas Cable Street party at Limehouse Town Hall, which I was really looking forward to, but I was too ill to get there. My priority was to be fit enough for the next day.

The Sunday was beautiful – there were upwards of 2,000 people, energised, united, diverse, with colourful banners, and a Yiddish marching band near the front. It was a powerful, meaningful demonstration remembering the battles of the past and committing to our multicultural future. Great speakers before the march at Altab Ali Park, which I chaired, and after the march at St George’s Park on the wonderful staging set up through the RMT, chaired by Megan Dobney of South East Region TUC. The 101-year-old Cable Street veteran Max Levitas spoke. Mike Rosen recited poignant poems. Julia Bard of the Jewish Socialists’ Group recalled the struggles not only against the fascists but also against the community establishment who, in 1936, told people to stay indoors. Jeremy Corbyn gave a powerful and very personal speech to great applause, which closed the rally. We had celebrated the great Battle of Cable Street – but not without a battle of our own.

present and for the future. Those who want to whitewash Mosley’s history of fascism and whitewash his antisemitism share the same circles as those, like David Irving, who wish to deny the Holocaust. They secretly dream of doing again what they deny ever happened.

present and for the future. Those who want to whitewash Mosley’s history of fascism and whitewash his antisemitism share the same circles as those, like David Irving, who wish to deny the Holocaust. They secretly dream of doing again what they deny ever happened. Last Sunday, slave trader Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol was daubed with paint, pulled to the ground, jumped on by joyful protesters, rolled along to the harbour and dumped in the River Avon. The events caused quite a splash. As Colston sunk ignominiously to the bottom, what rose to the surface was a long overdue national debate about statues that grace or rather disgrace our towns and cities, and reinforce a dominant history.

Last Sunday, slave trader Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol was daubed with paint, pulled to the ground, jumped on by joyful protesters, rolled along to the harbour and dumped in the River Avon. The events caused quite a splash. As Colston sunk ignominiously to the bottom, what rose to the surface was a long overdue national debate about statues that grace or rather disgrace our towns and cities, and reinforce a dominant history.

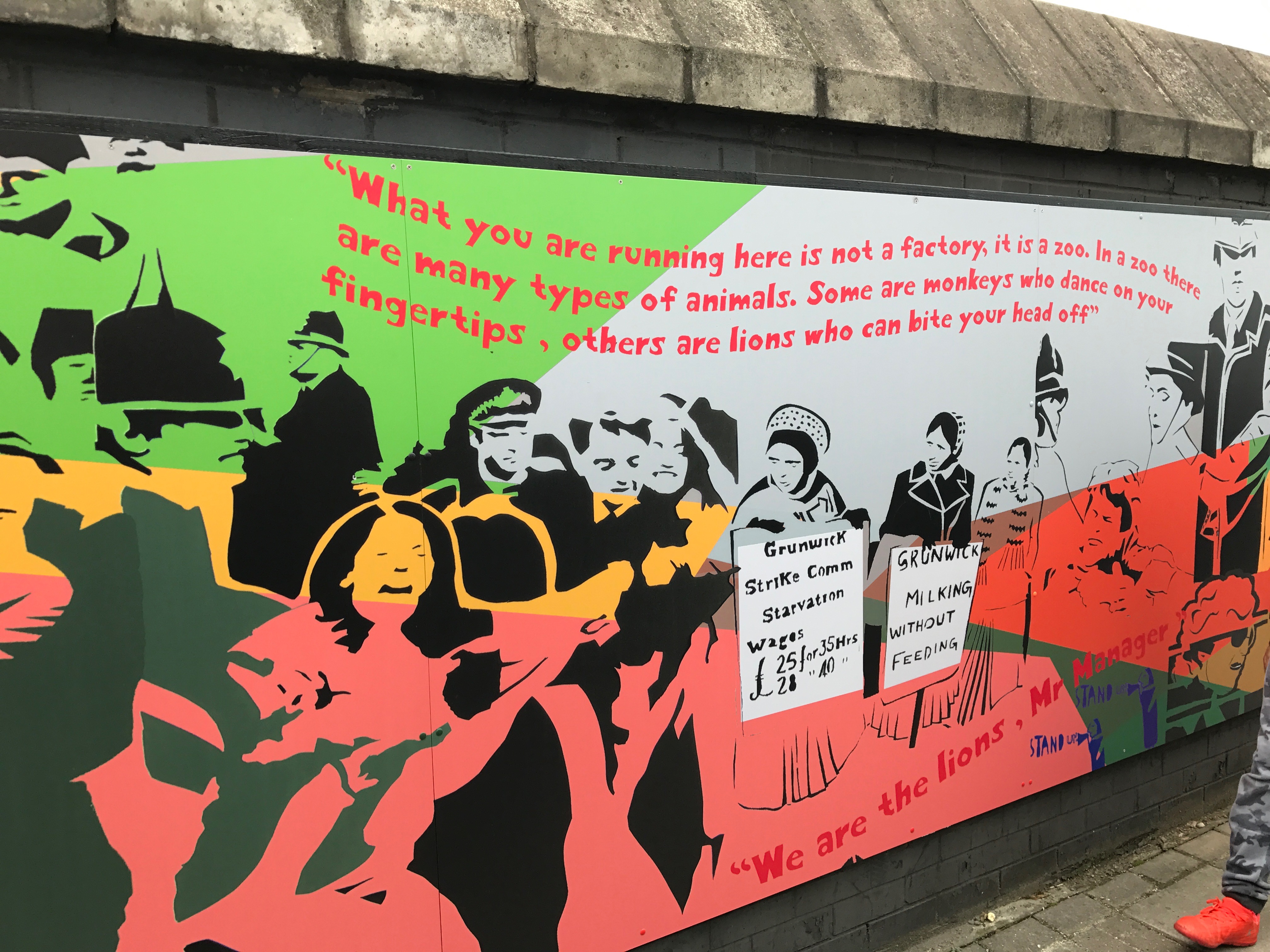

I actually prefer monuments to collective struggle such as the colourful and moving Cable Street mural, where you can almost hear the figures shouting and screaming, or the artistic monument to Spanish Civil War volunteers in Jubilee Gardens, both of which celebrate those who challenged fascism. Or the mural on the bridge on Dudden Hill Lane round the corner to the Grunwick Film processing factory in Willesden, where a strike committee headed by Jayaben Desai led a courageous battle by mainly female Asian workers in the late 1970s against super-exploitative and inhumane employers.

I actually prefer monuments to collective struggle such as the colourful and moving Cable Street mural, where you can almost hear the figures shouting and screaming, or the artistic monument to Spanish Civil War volunteers in Jubilee Gardens, both of which celebrate those who challenged fascism. Or the mural on the bridge on Dudden Hill Lane round the corner to the Grunwick Film processing factory in Willesden, where a strike committee headed by Jayaben Desai led a courageous battle by mainly female Asian workers in the late 1970s against super-exploitative and inhumane employers.

‘… five years of advance in the face of money power, press power, party power and Jewish power … during which the flame of the faith has grown within us until the blaze of our belief and of our determination lights the dark places of our land and summons our people as a beacon of hope and of rebirth.’

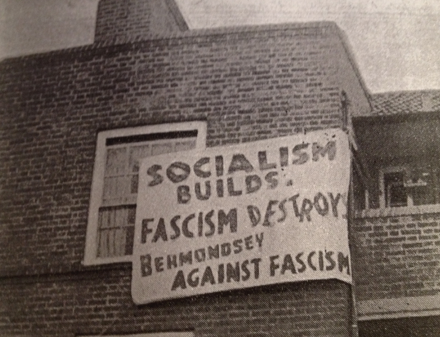

‘… five years of advance in the face of money power, press power, party power and Jewish power … during which the flame of the faith has grown within us until the blaze of our belief and of our determination lights the dark places of our land and summons our people as a beacon of hope and of rebirth.’ from their chosen route and led them instead around the rim of the borough. The Daily Worker reported that, when they finally returned to their planned path and reached Jamaica Road, they ‘met another barricade … of men, women and children from the great flats that Labour has built in Bermondsey’. Banners hanging from these blocks proclaimed: ‘Socialism builds. Fascism destroys. Bermondsey against fascism.’

from their chosen route and led them instead around the rim of the borough. The Daily Worker reported that, when they finally returned to their planned path and reached Jamaica Road, they ‘met another barricade … of men, women and children from the great flats that Labour has built in Bermondsey’. Banners hanging from these blocks proclaimed: ‘Socialism builds. Fascism destroys. Bermondsey against fascism.’