In 1882, Robert D. Fitzgerald, Irish-born Australian and dedicated amateur naturalist, published Volume I of Australian Orchids. In it, he described an orchid that could only be found in “the granite hills near Albury”. He named it Caladenia concolor*.

Towards the end of the twentieth century, sightings of this orchid had become extremely rare. Then, in 1995, a local naturalist (who prefers to remain anonymous) found some growing on the Nail Can Hill Range and recognised them as a unique, fragile and endangered species. He alerted Paul Scannell, the curator of the Albury Botanical Gardens.

From that point a dedicated group of professionals and volunteers have been working to save our Crimson Spider Orchid. This article is the story of that long, complex and difficult effort.

And please read to the section titled New Hope (or skip to it if you’re that kind of reader) because …

this story ends with a breakthrough.

But first, some facts.

Description

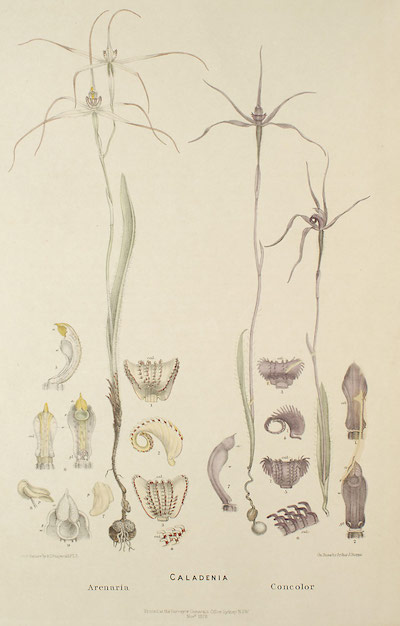

The flower has five spreading petals and sepals, purple-red in colour, around 4.5 cm long, and a broad down-curled purple labellum with curving marginal teeth. The stem is hairy and grows 15 to 30 cm tall and is also dark purplish red, bearing one or two flowers. The single leaf is narrow and thin, 5 to 15 mm across.

“It is very remarkable for the darkness and uniformity of colour of the flower and stem. The edges of the labellum are much more acutely divided than in C. arenaria, and the column much narrower and simpler in form. It flowers in October.” Fitzgerald, p177.

The flowers have a strong scent which has been said to be like the smell of a hot motor, although Dr Noushka Reiter, of the Australian Network for Plant Conservation, suggests they have a “distinctly mandarin flavoured smell”. (Media Release, ANPC, 2014) LINK

Caladenia concolor is deciduous. It produces a single leaf during autumn or winter, flowers in September or October, and survives the dry summer and early autumn as a dormant tuber. Flowering does not take place every year for reasons that are not fully understood (Crimson Spider Orchid Profile, no date, NSW OEH).

The crimson spider orchids of Nail Can have a longevity of around 16 years (Paul Scannell, private communication, 2017). Spider orchids in general reproduce from seed (Backhouse & Jeanes 1995). Fruits normally take five to eight weeks to reach maturity following pollination and each mature capsule may contain tens of thousands of microscopic seeds that are dispersed by the wind when the capsule dries out (Todd 2000). Seedlings will only germinate 25 mm away from the adult plant (Paul Scannell.)

Habitat

Orchids of this kind typically grow in grassland, heathland or open sclerophyll forest, on well-drained, gravelly sand and clay loams (Backhouse & Jeans 1995, NSW TSSC 2011, Coates et al., 2002; NSW NPWS 2003).

The Caladenia concolor exists in regrowth woodland on granite ridge country in the Nail Can Hill Crown Reserve outside of Albury and also in populations in the Chiltern Forest and at Mt Jack in Victoria. These populations have small variations in the appearance of petals, but are known as species affiliates (Paul Scannell in private communication).

Clearing took place in the Nail Can reserve in the early part of the century but despite a history of grazing and burning, the regenerating woodland has retained a high diversity of plant species, including other orchids.

Here are some of the species in the area.

The dominant trees are Blakely’s Red Gum (Eucalyptus blakelyi), Red Stringybark (E. macrorhyncha), Red Box (E. polyanthemos) and White Box (E. albens). The understorey is made up of a variety of shrubs, herbs and grasses including Silver Wattle (Acacia dealbata), Native Cherry (Exocarpos cupressiformis,) Hickory Wattle (A. implexa,) Mountain Grevillea (Grevillea alpine), Austral Indigo (Indigofera australis), Hop Bitter-pea (Daviesia latifolia), Showy Parrot-pea (Dillwynia sericea), Common Beard-heath (Leucopogon virgatus), Slender Rice-flower (Pimelea linifolia), Purple Coral-pea (Hardenbergia violacea), Spreading Flax-lily (Dianella revolute), Many-flowered Mat-rush (Lomandra multiflora), Kangaroo Grass (Themeda australis), Snow Grass (Poa sieberiana) and Wallaby Grasses (Austrodanthonia spp.).

Most terrestrial orchids have evolved under conditions that include summer fires, which occur when the plants are dormant. Some species flower vigorously following fires, possibly because of reduced competition from other plants (Backhouse & Jeanes 1995; Todd 2000). Variation in rainfall and temperature can influence flowering. Flowering is often aborted when periods of sustained hot, dry weather follow flower opening (Todd 2000).

Ecology

The orchid will only thrive in the presence of two other specific species.

Firstly, the usual pollinator for spider orchids is a male wasp, attracted by a scent that mimics a female pheromone (Backhouse & Jeanes 1995; NSW National Parks 2003, Todd 2000). Other orchids use food-deception to be pollinated. Dr Noushka Reiter notes that it emits a mandarin-scented smell and believes that it accesses pollination through food-deception (ABC TV Gardening Australia, Episode 25: 19/08/2017, Australian Network for Plant Conservation media release, 2014).

Secondly, most spider orchids grow in a complex relationship with mycorrhizal fungi which live on their root systems or rhizomes and help them to assimilate nutrients. The long term persistence of a suitable mycorrhiza is critical for growth and development of the orchid (Todd 2000, Warcup 1981).

Endangered

The Caladenia concolor has several known populations in Victoria with less than 1000 known remaining plants in total.

“It’s really at a point where, unless we do something within our lifetime we’re likely to lose this particular species,” Dr Noushka Reiter, Australian Network for Plant Conservation (Fogarty 2014).

Caladenia concolor is a fragile plant, subject to threats from environmental degradation. It was listed as Vulnerable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth EPBC Act) effective from the 16 July 2000.

With only a few tiny populations left in the wild, there are concerns that there is insufficient genetic diversity, which leaves populations more vulnerable to disease and environmental challenges.

In the last few years, climate change, with increasingly dry autumns, has meant that the stringybarks in the reserve have died off, and this has opened up the canopy. Increased sunlight has led to reductions in mosses and lichens in the orchids’ environment. Encroaching housing estates have led to an increase of the density of kangaroo populations, so that more of the understory is being eaten (Paul Scannell private communication).

“Threats include inappropriate fire regimes, clearing, mountain bike and trail bike trails, grazing by anything hungry and firewood and bush rock collection.” Paul Scannell, Curator Albury Botanic Gardens, Australian Network for Plant Conservation.

Invasive weeds compete with orchid species for resources (Duncan, Pritchard and Coates 2005, NSW NPWS 2003). In the Nail Can Reserve there are threats from noxious weeds such as blackberry and St Johns Wort, and from annual exotic grasses of the Briza genus, the quaking grasses (National Parks and Wildlife Service, 2003).

Fires that occur in autumn, winter and spring, after the orchid plants shoot, but before seed is set, may pose a threat. If the habitat was burnt while the species was flowering or in fruit, this would destroy the reproductive effort for that year and possibly weaken tubers by limiting photosynthesis. Too frequent fire may pose a threat by altering the habitat, removing organic surface materials and negatively impacting pollinators and fungal agents.

Protecting the crimson spider orchid

Since the Albury population was rediscovered in 1995, a number of actions were undertaken by concerned local residents in conjunction with the Albury Botanic Gardens and the NSW Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Natural Resources (DIPNR).

Fencing has been improved, with the provision of locked gates. This has restricted vehicle access, grazing, rubbish dumping and the removal of firewood. Attempts were begun to control noxious weeds and rabbits.

During 1999 fencing and weed control measures were funded by DIPNR and the NSW Biodiversity Strategy, and were undertaken by the Australian Trust for Conservation Volunteers. Volunteers worked on localised hand removal of Briza.

In 2001 NSW Parks and Wildlife Service established a Recovery Team and began developing a Recovery Plan (see NSW NPWS 2003).

The fire hazard is now managed through firebreaks, a system of mosaic burns and controlled grazing in restricted areas and at restricted times of the year. The area in which the Crimson Spider Orchid is found is being excluded from all planned fire.

Data Collection

Since its rediscovery, the population has been closely monitored. Data has been collected on leaf emergence, flowering and pod formation for individual plants. From an initial four plants observed in 1995 the numbers now under observation have increased to around 80.

In spring 2000, extensive surveys for further populations of the Crimson Spider Orchid were carried out. Areas searched included potential habitat in Nail Can Hill, Tabletop Mountain and Yambla Range, Holbrook and Tarcutta Hills. One additional individual was found in the vicinity of the Nail Can Hill population, however, no new populations were discovered. The permanent tagging of all individuals commenced in 2003.

Hand Pollination

There are concerns about the absence of a suitable pollinator and that extremely low numbers of plants might restrict natural pollination. Hand-pollination work commenced in 2000. This provided a small quantity of seed for ex-situ propagation. Material was also collected in order to isolate the fungal associate essential to successful ex situ propagation.

The work proved difficult.

New Hope

In 2014 the Australian Network for Plant Conservation (ANPC)** announced the successful germination of Crimson Spider Orchid. A team led by Dr Noushka Reiter from the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria (RBGV), with the ANCP, hand-pollinated plants in the field, and managed to get some seed and grow plants in the laboratory.

“Scientists have been trying to germinate these species for several years … Australian terrestrial orchids rely on a specific ‘type’ of mycorrhizal fungi to germinate and sustain their growth …We just needed to find the right fungus, and we finally did” (Dr Noushka Reiter, see ANCP media release, 2014).

At laboratories run by the RBGV, where a ‘happy team’ of volunteers, mostly retired professionals and scientists, are working on the conservation of the spider orchid .There is a 10 year program to restore and reintroduce this species.The major parties in this work are the Saving Our Species Fund, the Office of Environment and Heritage and Murray Local Landcare Services who have sponsored RBGV for propagation and pollinator research. (Dr Charles Young from RBGV, private communication, 2017).

The next step is to successfully reintroduce propagated plants into the wild. Being able to do this is vital to the species’ long term survival. Seedlings are being planted in secret suitable locations in the reserve. Populations need fungi to be in the soil year after year in order to survive.

“To further complicate things, each species is pollinated by a unique insect. We don’t yet know what pollinates the Crimson Spider-orchid.” Dr Reiter.

Similar orchids

The Crimson Spider Orchid (Arachnorchis concolour) is unique to the Albury, Dederang and Chiltern area. Around the time they were rediscovered on Nail Can, these plants were thought to be the same species as populations near Cootamundra. They are now known to be different species: the Bethungra Spider Orchid and the Burrinjuck Spider Orchid.

The Bethungra Spider Orchid occurs between Bethungra and Cootamundra. The Burrinjuck Spider Orchid is found in the Burrinjuck Waters State Park and Burrinjuck Nature Reserve.

*In 2001 the orchid was reclassified and renamed, Arachnorchis concolour, by Mark Clements and David Jones of the Australian National Botanical Gardens (see Clements and Jones, 2008) but Arachnorchis was not accepted as a genus by the heads of the botanic gardens or the Vic or NSW census, and it remains Caladenia (Dr Noushka Reiter and Dr Charles Young, in private communication).

The ANPC is a national non-profit, non-government organisation dedicated to the promotion and development of plant conservation in Australia. For further information on the Orchid Conservation Program, contact the ANPC on 0428 781277 or visit the ANPC website: http://www.anpc.asn.au/projects/orchids

References and further reading

ABC TV, Gardening Australia, Episode 25 (2017), http://www.abc.net.au/gardening/video/download.htm

Australian Network for Plant Conservation (2004), “Crimson Spider Orchid: Caladenia concolor”. https://www.flickr.com/photos/anpc/8743658096

Australian Network for Plant Conservation (2014), “Media Release: New Hope for Rare Orchids”. http://www.anbg.gov.au/anpc/projects/Media%20Release%20ANPC%20Orchids%20OEH%20March%202014.pdf

Australian Network for Plant Conservation (2017) “The ANPC Orchid Conservation Program”. http://www.anpc.asn.au/orchids

Backhouse, G. & Jeanes, J. (1995). The orchids of Victoria. Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, Victoria.

Carr, G.W. (1999). “Mellblom’s Spider-orchid”. Nature Australia, 26, 18-19

Clements, Mark and Jones, David (2008) Australian Orchid Name Index. Canberra ACT: Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research/Australian National Herbarium https://www.anbg.gov.au/cpbr/cd-keys/orchidkey/Aust-Orch-Name-Index-08-06-13.pdf

Coates, F., Jeanes, J. and Pritchard, A. (2002). “Recovery Plan for Twenty- five Threatened Orchids of Victoria, South Australia and New South Wales 2003 – 2007.” Department of Sustainability and Environment, Melbourne. http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/publications/recovery/25-orchids/index.html.

Duncan, M., Pritchard, A. & Coates, F. (2005). “Major Threats to Endangered Orchids of Victoria, Australia”. Selbyana, 26, 189-195. http://www.jstor.org.ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/stable/41760190

Fitzgerald, (1882). Australian Orchids. Sydney, Thomas Richards, Government Printer. http://bibdigital.rjb.csic.es/ing/Libro.php?Libro=5805

Fogarty, Nick 2014 “Breakthrough may save rare Riverina orchid”. http://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2014/04/04/3978657.htm

Gilbert, L.A. (1972) , ‘FitzGerald, Robert David (1830–1892)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fitzgerald-robert-david-3527/text5431, published first in hardcopy 1972, accessed online 9 September 2017.

Harden, G (Ed.). 1993. Flora of New South Wales. Vol 4. Kensington, NSW: University of NSW Press.

Jones, David (1988), Australian Native Orchids. French’s Forest, NSW: Reed Books.

Monument Hill Parklands Association Inc. and the Albury Wodonga Field Naturalists Club Inc. (2013), Along the Bush Tracks: Albury-Wodonga. http://www.alburyconservationco.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/BUSH-TRACKS.pdf

NSW Office of Environment and Heritage (1997) “Crimson Spider Orchid Profile”. Last updated Aug 2017. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/threatenedspeciesapp/profile.aspx?id=10122

NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (2003) Draft Recovery Plan for the Crimson Spider Orchid (Caladenia concolor) (Including populations at Bethungra and Burrinjuck to be described as two new species) Hurstville, NSW. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/nature/recoveryplanDraftCaladeniaConcolor.pdf

Threatened Species Scientific Committee, Australian Government Department of Environment and Energy (2016), “Conservation Advice: Caladenia concolor, crimson spider orchid”. http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/species/pubs/5505-conservation-advice-16122016.pdf

Todd, J.A. (2000). Recovery Plan for Twelve Threatened Spider-orchids Caladenia taxa of Victoria and South Australia 2000 – 2004. Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Melbourne, Victoria. http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/5673cd4d-1802-4927-85e5-4bdbf947ba58/files/12-orchid.pdf

Warcup, J.H. (1981). The mycorrhizal relationships of Australian orchids. New Phytology 87, 371-381. Referred to by Threatened Species Scientific Committee above.