Drawings by Piero della Francesca

What more is there to say about Piero della Francesca? I am not acquainted with all or even most of the literature devoted to him, but it is clear that every work of his has been exhaustively described, analysed, interpreted and contextualised by many experts over the years. Some works, like the Urbino Flagellation remain resistant to definitive explanation. It is possible that more may be discovered archivally to clarify chronology in the early and late parts of his career. However, there is one area of study that is strangely unvisited: no one seems interested in asking how this painter drew anything other than tiny diagrams for mathematical treatises.

The omission is strange to me because drawing is so obviously a necessary part of the process involved in making the works we admire: how could a narrative programme as complex as that of the Arezzo frescoes have been transferred from mind to wall without it? Is it not likely therefore that he made drawings off the wall? Of course, it is always possible with artists who worked so long ago that no drawings have survived; but it is certainly worth a search before coming to that conclusion. This I have undertaken with results that I believe to be positive and defensible, in the form, so far, of three unrelated sheets.

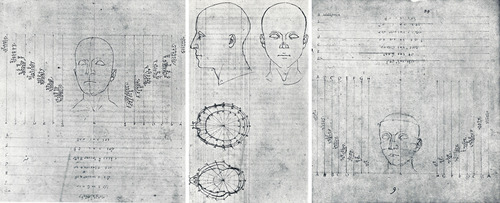

Firstly, one needs to ask what kind of drawing Piero would be likely to make, given the character of his painted work. A preliminary observation narrows the field immediately: surely someone as interested in geometry as Piero clearly was must have been habituated to drawing lines precisely, because geometrical relationships are most effectively represented on paper in linear form. If we start from what we have, the mathematical diagrams, that is what we see.

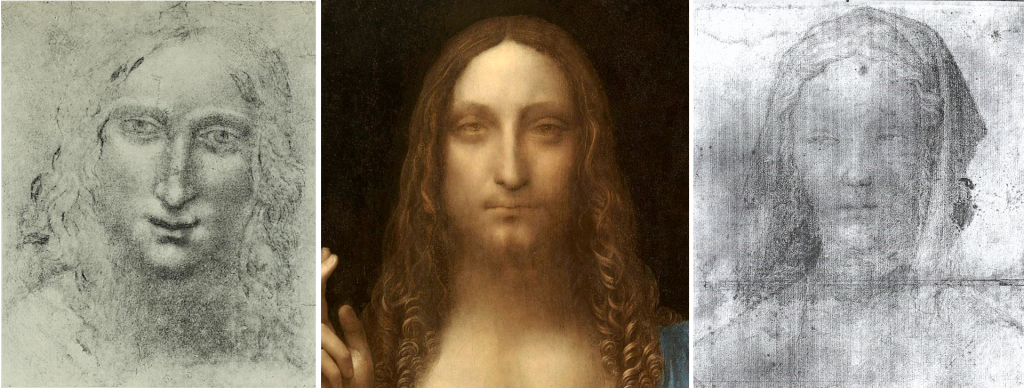

fig. 1:

The strong implication, however, is that there is geometry underlying all forms, therefore all forms may be described and explained through a series of connected lines. The implication amounts to a passionate credo. Leonardo was to have much the same attachment to drawing as the primary tool with which to simultaneously discover and explain the structures of the visible world, though he was to make far more use of shading by hatching to indicate changes of plane.

It is a possibility, but I think unlikely, that a man thus habituated to explaining volumetric forms to himself (and others) - how a human head relates to a neck, or a capital to a column - by the drawing of lines would adopt a different approach in his non-didactic, more creative work and start describing form with a lot of deep shading by cross~hatching, textural marks, scribbles and so forth. Much more likely would be the continuing expression of his belief that everything, an eye, a nose, even locks of hair can be described separately and together in a linear way, and that only the lightest shading by single hatching is needed to suggest modelling on curved surfaces.

The other feature I would look for in a Piero drawing, if it was a face or a figure, is something of the plumb-lined erectness and dignity of bearing that is so evident, and so impressive, in the frescoes and paintings.

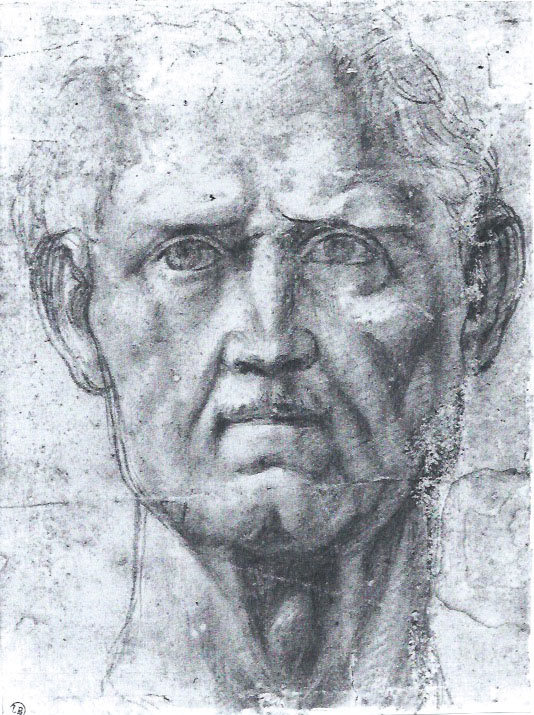

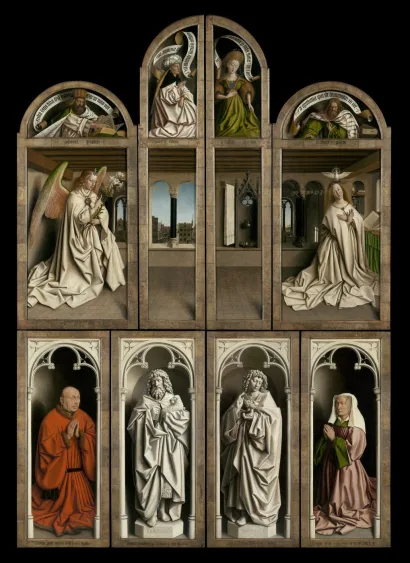

fig. 2: Bloch Drawing

Here, then, is my primary candidate, discovered among reproductions of works attributed to the ‘School of Padua’: a drawing roughly 14 by 9 inches, done in pen and ink over light chalk, of a young man wearing a cap, seen full-face. Once in the Victor Bloch collection, it was sold by Sotheby’s on 12 November 1964, Lot 9 - to whom I know not.

At this point one has to stop writing or talking and let one’s readers’ eyes pan slowly like a camera over assembled comparanda to judge if my proposal - that this is an authentic Piero drawing - is credible on the usual twin criteria of likeness and of quality. Is the Bloch drawing (let us call it that) sufficiently like heads from accepted works by Piero, and is it of sufficient quality? With a drawing like this there is no documentary proof either way, but on the negative side, I have never found Marco Zoppo or any Paduan artist drawing like this, nor, if I consider the very high quality of the drawing, can I think of any artist of the time, from whatever region, who drew at this level of control, sophistication and elegance who did not draw differently in his own known style.

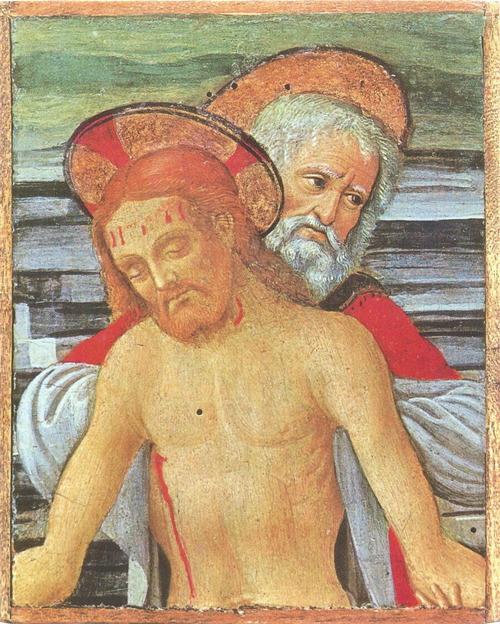

fig. 3: Zoppo Comparison

On the positive side we have a notably linear style of drawing of the kind to be expected; we have the sparing use of single-hatch shading to give a very light and delicate but totally convincing modelling; and we certainly have the erect bearing, the clear, open expression in the eyes, all of which is essential to Piero. At a more detailed level we can look comparatively at how the nose is modelled, the delineation of the eyes with their particular curves and linking of upper and lower lids, the shaping of the lips with emphasis on the median line as in Holbein, the overall elliptical form of the face, the ear-lobe, the treatment of hair curls, each of which resembles a grass-blade or curled leaf… and so on. The calm dignity of the young man is given animation by his being so close to us and by his looking to his left at us and slightly down, an intimacy reinforced, if accidentally, by the image of him being off-centre.

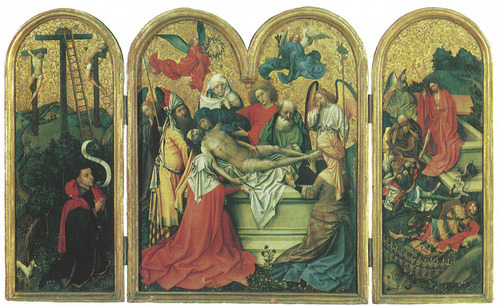

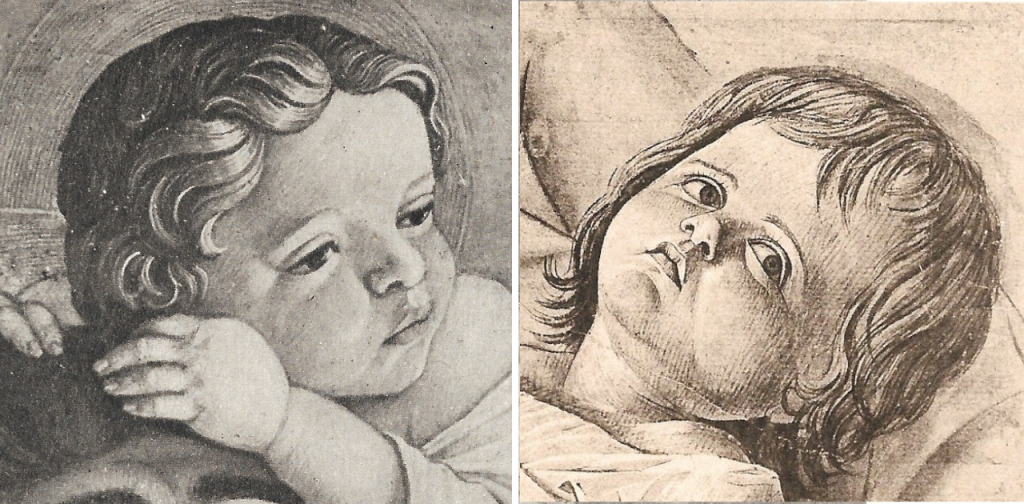

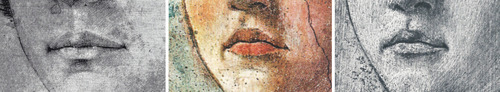

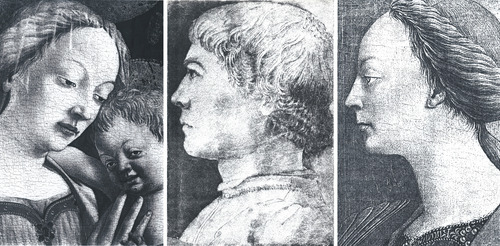

fig. 4: Faces

Since connoisseurship operates primarily through visual argument it will be helpful here to study some details of the Bloch drawing vis à vis comparable ones in the Arezzo frescoes and elsewhere amongst Piero’s paintings.

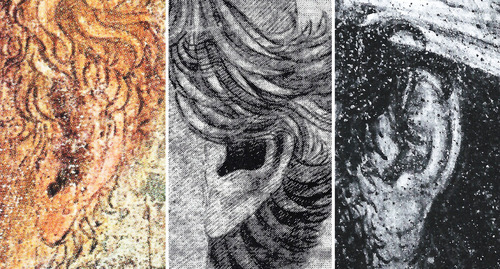

fig. 5: Hair

fig. 6: Eyes

fig. 7: Lips

fig. 8: Ears

My conviction, as now declared, is that this is a drawing by Piero, perhaps not from the period of the Arezzo frescoes but a little earlier, and that whoever now owns it - not a museum as far as I know - is the possessor of a wonderful thing, finer by a good way than anything Marco Zoppo could have drawn. I must leave the comparisons I offer (and others could add to) to work, or not, in favour of my attribution, only adding that if I am mistaken there is a problem to be dealt with: if this is not by Piero, then who is good enough, and who is likely enough, to be an alternative candidate?

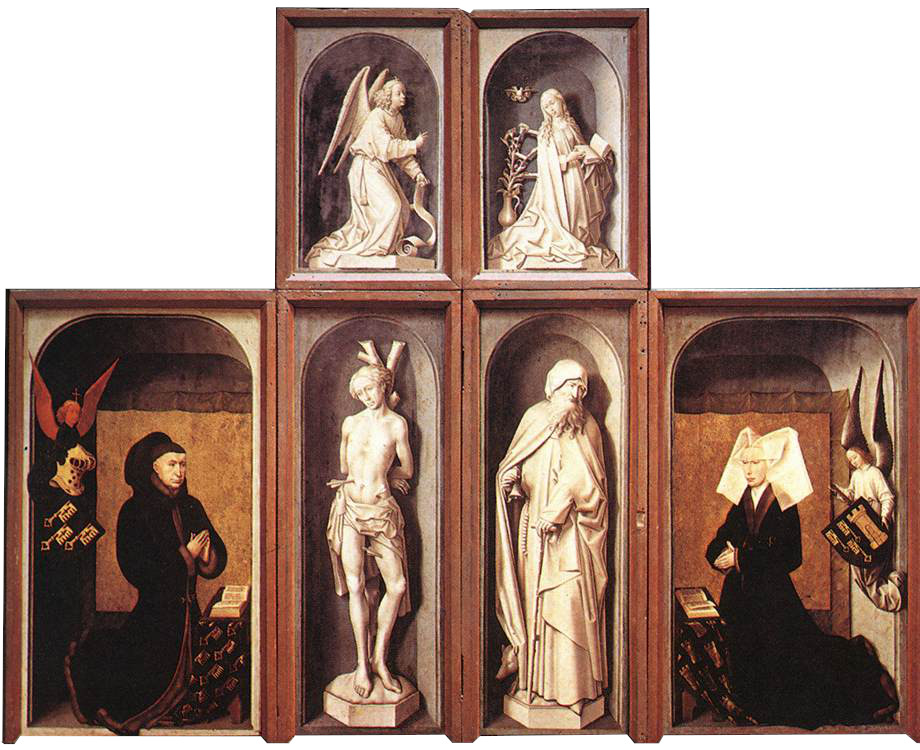

fig. 9:

If l am right about the Bloch drawing, then two further drawings can be proposed. The first, and better known, is another portrait of a young man, this time in profile, from the Gabinetto of the Palazzo Corsini in Rome; 10 by nearly 8 inches, it is drawn in pen and brown ink with a dark brown wash for background.

fig. 10:

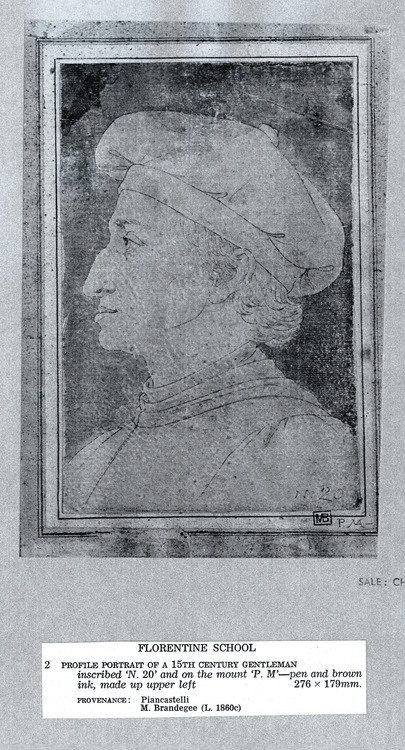

The second, very similar in technique, is a profile portrait, also head and shoulders and wearing a cap, but of a middle-aged man with an aquiline nose and a jutting lower lip, who just might be Cosimo de Medici. It was sold at Christie’s on 30 September 1975, Lot 2, but again I do not know to whom.

fig. 11:

fig. 12:

Both these drawings show signs of being more rapidly executed studies than the Bloch drawing: less trouble has been taken over the hair and there is no hatching. However, there is great fluency and refinement in the line, which is all-defining. There are many comparable profiles in the frescoes at Arezzo, which inclines me to date these drawings later than the Bloch one, to that period of intense activity when Piero was very likely drawing in more haste but at the top of his form as a linear draughtsman. I see no reason to attribute either of them to a Pollaiuolo or any other Florentine.

fig. 13:

Pure, or nearly pure line drawings such as these three that I ascribe to the hand of Piero require of the artist not only a masterly control but also an exceptionally clear understanding of form, because the line has to do so much to convey it and it has nowhere to hide. Some artists are still tempted by the example of Botticelli perhaps, Ingres, Picasso or Kitaj, to try their hand at pure line drawing but are handicapped by lack or such understanding and control. Yet when it succeeds, such drawing has a lyric grace, exemplified on the best Greek vases, which is hard to match.

As it happens there is an instructive and relevant illustration of these matters in the form of yet another profile portrait of a youth, in the British Museum. It has been ascribed, as was the Bloch drawing, to the ‘Paduan School‘ and likewise thought ‘close to Zoppo’ but I am convinced it is by Domenico Veneziano, so like is the profile to that of St Lucy in that painter’s Saint Lucy Altarpiece in the Uffizi.

fig. 14:

Domenico Veneziano was a good painter who has left us fine things: his predella panel of a street scene at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge is a small gem of the early Renaissance. However, the difference in quality between this BM drawing and the Bloch one is so apparent to me that I find it very disappointing, from a critical point of view, that the two have ever been linked as possibly by the same hand. In the BM drawing there is a lot or hatching but it does not describe the form nearly as convincingly as Piero manages with less or none. In the treatment of hair, Piero’s ‘grass blade’ locks may well derive from those of Domenico, with whom he had lived and worked in Florence in the early 1440s (a decade before the Arezzo cycle), but in the BM drawing we see a more complicated pattern resembling strands of seaweed flowing underwater. The lines in Domenico’s drawing nowhere exhibit the sureness, subtlety and grace that we see in Piero’s. The comparison is instructive of that superior draughtsmanship; it reveals the greater artist.

Why does it matter to have three non-mathematical drawings by Piero della Francesca? One answer might be the further question: why does it matter to have drawings by anyone? Many would say that drawings are, or can be, intrinsically beautiful, so worth having per se; and this, for me, is true of the Bloch drawing. Our curiosity cannot be denied, however, and believing it to be by the hand of an artist of Piero’s stature adds a great deal because, once again, a drawing proves to be a very personal confirmation of how a particular artist sees the world: if he drew like this, he would paint like that, because he saw and thought in this way. The drawing-as-confirmation has a role for us as critics, but it also has a guiding role when it reminds, as it should, anyone who elects to make a physical intervention in the frescoes or the paintings that these are the essential features to be conserved. Here they are: if you neglect the reminder and in any way obliterate them or lessen their impact, you are betraying the imagination of this artist. The drawing tells us where the emphasis lies and what the instinctive stylistic preferences are.

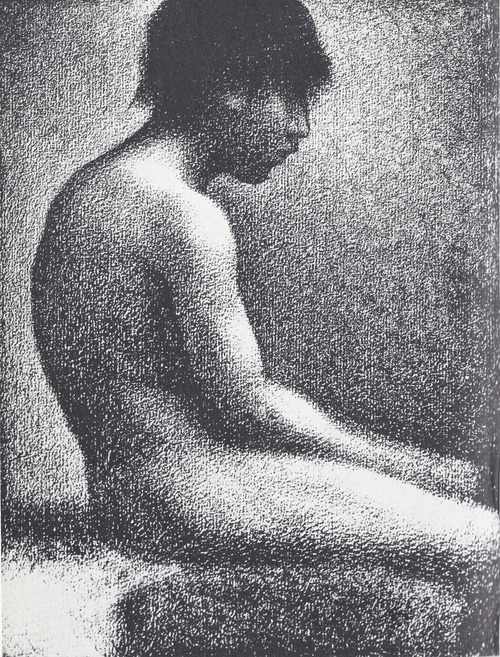

What has just been said applies to any drawing by any artist. In the case under discussion I hope we now know that Piero della Francesca’s belief that everything could be described by line was as beautifully expressed in drawings as it was in his paintings. How strange it is in one way (and not at all in another) to think of Seurat’s conté drawings, all tone like an early photo, and know that he copied, and greatly admired, the frescoes of the painter who drew the Youth in the Bloch Collection.

fig. 15:

What did the young Seurat admire in Piero della Francesca? The answer, I think, is to be found in Piero’s devotion to linear definition: everything is bound by a line and that edge has to be delineated with the utmost precision if it is to describe on a flat surface what is modelled in three dimensions. Only if the edge is exact enough can the form be read or inferred. A Seurat drawing has no boundary lines, but where the silhouette of something ends and the surrounding tone begins is a profile every bit as refined and expressive as the linear profiles in Piero that these drawings illustrate. If we find no others we have reason to be grateful that our understanding of Piero’s art has been enriched by them. As he drew, so he painted.

fig. 16:

Footnotes:

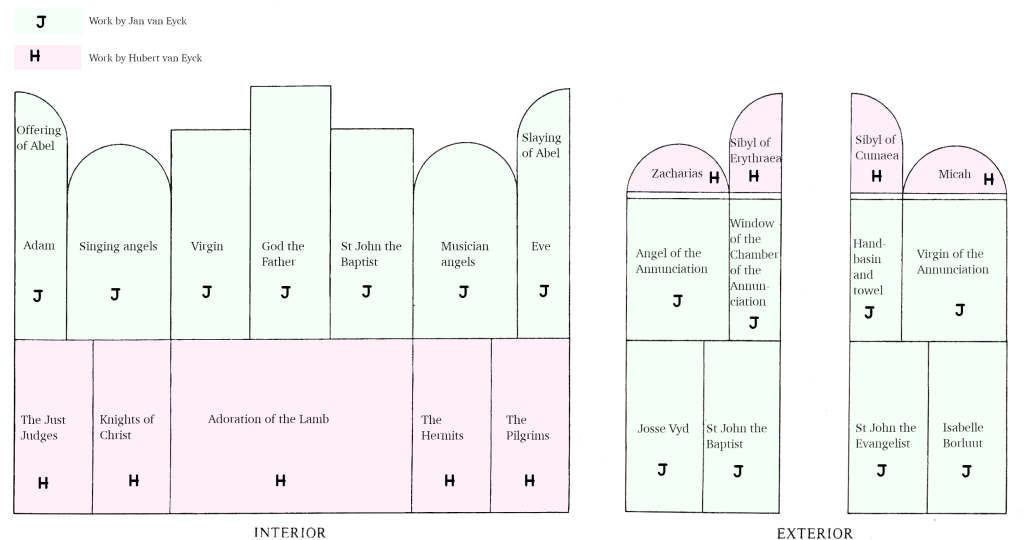

fig. 1: a) Diagramatic drawing illustrating Piero’s treatise ‘De Prospetiva Pingendi’. Ambrosiana, Milan. b) Diagramatic drawing illustrating Piero’s treatise ‘De Prospetiva Pingendi’. Biblioteca, Parma. c) Ditto fig. 2: Head of a Young Man wearing a cap. Drawing, pen and ink over black chalk (14 ¼ x 9 1/8 in) Victor Bloch Sale, Christie’s, London, 12 November 1964 (Lot. 9). Sold as ‘Paduan School, third quarter of the 15th century’ with suggested attribution to Marco Zoppo. Hereafter referred to as ‘Bloch drawing’. fig. 3: a) Marco Zoppo Sketchbook, British Museum, London Cat. Italian Drawings XIV-XV Cent. No.260 b) Bloch drawing c) Marco Zoppo Sketchbook, British Museum, London Cat. Italian Drawings XIV-XV Cent. No.260 fig. 4: a) Angel’s head from Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels, Brera Gallery, Milan. b) Bloch drawing. c) Head of Madonna del Parto, Museo Monterchi. d) Head of an Angel. San Francesco, Arezzo. e) Head of Lady attending Queen of Sheba adoring Holy Cross, San Francesco, Arezzo. f) Head from Children of Adam in Adam announcing his Death, San Francesco, Arezzo. fig. 5: a) Detail of old man in The Death of Adam, San Francesco, Arezzo. b) Bloch drawing. c) Angel’s head from Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels, Brera Gallery, Milan. fig. 6: a) Head of Lady in St Helena and her Ladies, San Francesco, Arezzo. b) Bloch drawing. c) Head from Heraclius restores the Cross to Jerusalem, San Francesco, Arezzo. fig. 7: a) Bloch drawing. b) Daughter of Adam from the Children of Adam, San Francesco, Arezzo. c) Detail, Madonna del Parto, Museo Monterchi. fig. 8 a) Daughter of Adam from the Children of Adam, San Francesco, Arezzo. b) Bloch drawing. c) Workman leaning on spade from Discovery of the Cross, San Francesco, Arezzo. fig. 9: Profile drawing of Young Man, pen and ink and brown wash, Gabinetto, Desegni e Stampe, Galleria Nazionale Palazzo Corsini, Rome. Hereafter: Corsini drawing. fig. 10: Profile portrait of man with aquiline nose, pen, brown ink and wash (276 x 179mm), Sale Christie’s, London, 30th September 1975 (Lot. 2) Sold as ‘Florentine school’. Hereafter: Drawing, Man with aquiline nose. fig. 11: a) Drawing, Man with aquiline nose. b) Portrait of Cosimo de’ Medici. Attributed to Bronzino, Museo Medici-Riccardo, Florence. fig. 12: a) Detail, The Proof of the Cross, San Francesco, Arezzo. b) Head from Heraclius restores the Cross to Jerusalem, San Francesco, Arezzo. c) Corsini drawing. d) Detail of St Helena in The Discovery of the Cross, San Francesco, Arezzo. e) Corsini drawing. f) Detail of the Burying of the Cross, San Francesco, Arezzo. fig. 13: a) Detail, Eve in old age in The Death of Adam, San Francesco, Arezzo. b) Drawing, Man with aquiline nose. c) Head of Federigo da Montefeltro. Diptych of Duke and Duchess of Urbino, Uffizi Gallery, Florence. d) Head from Victory of Heraclius over Chosroes, San Francesco, Arezzo. e) Head from the Burying of the Cross, San Francesco, Arezzo. f) Head from Victory of Heraclius over Chosroes, San Francesco, Arezzo. fig. 14: a) Detail, Virgin and Child by Domenico Veneziano, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. b) Drawing, ‘Paduan School, 15th Century’ pen, ink and wash, British Museum, London. c) Detail of St Lucy from St Lucy Altarpiece, Uffizi Gallery, Florence. fig. 15: a) Georges Seurat, Conté crayon drawing of figure for Baignade (National Gallery, London), Private Collection, London. fig. 16: a) St Julian, Fresco fragment, Pinacoteca, Borgo San Sepolcro. b) Bloch drawing. c) Saint, San Francesco, Arezzo.