Antonello Da Messina

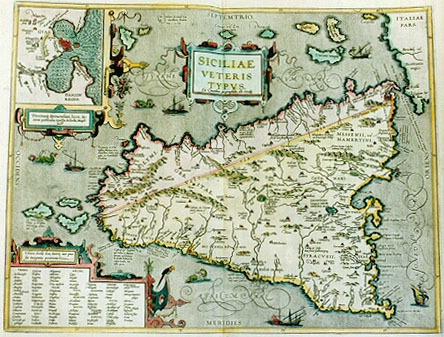

Terra tribus scopulis vastum procurrit in aequor

Trinacris a positu nomen adepta loci

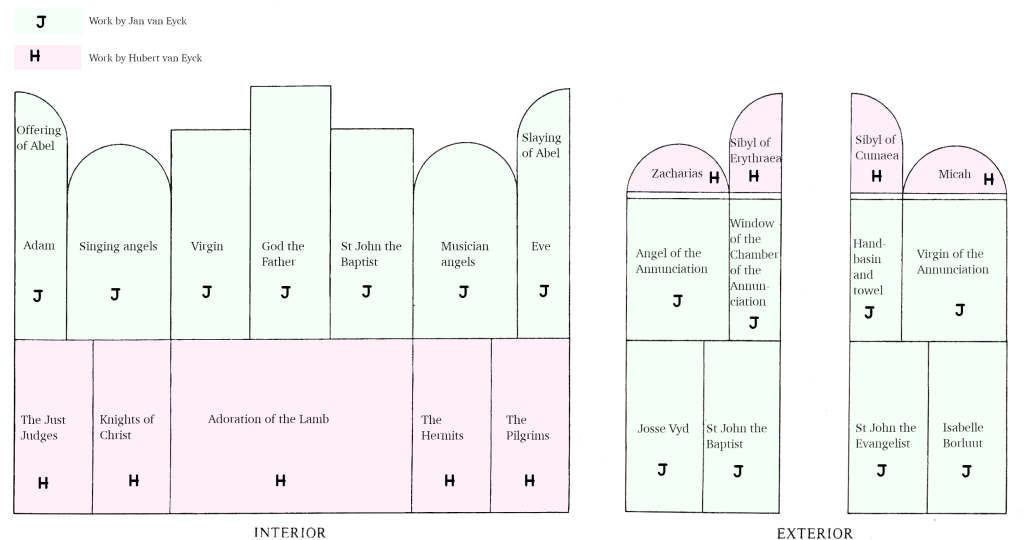

Ovid, I think; Sicily for sure, the three-pointed, three-caped island that in 1430 saw the birth of Antonello da Messina, arguably its greatest painter and definitely the finest celebrant of that magical coastal scenery which still draws many of us to it. He is the Van Eyck of the Mediterranean, using the new medium of oil painting to depict, with the same clarity and refinement that both men found in the human face, the face of the land he loved: not the wild mountains, not Etna (which only a Petrarch would have climbed), but the quiet coast and the fertile, settled countryside behind it, dotted with buildings, churches, castles, barns, and people walking and riding the intersecting paths.

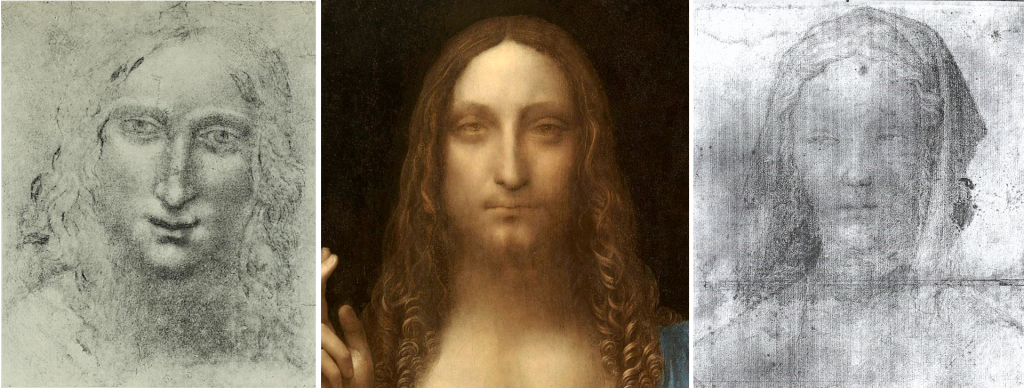

fig. 1

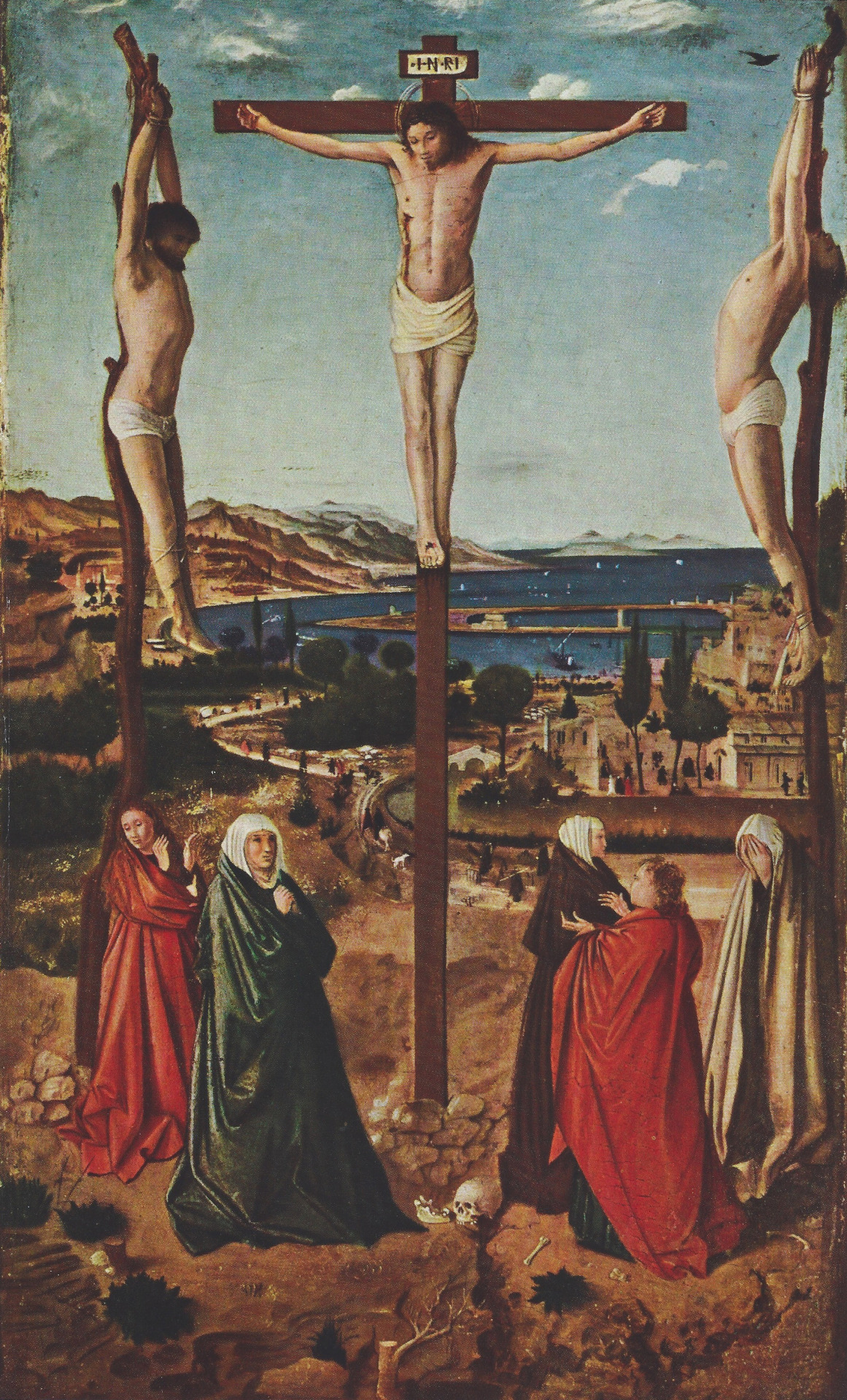

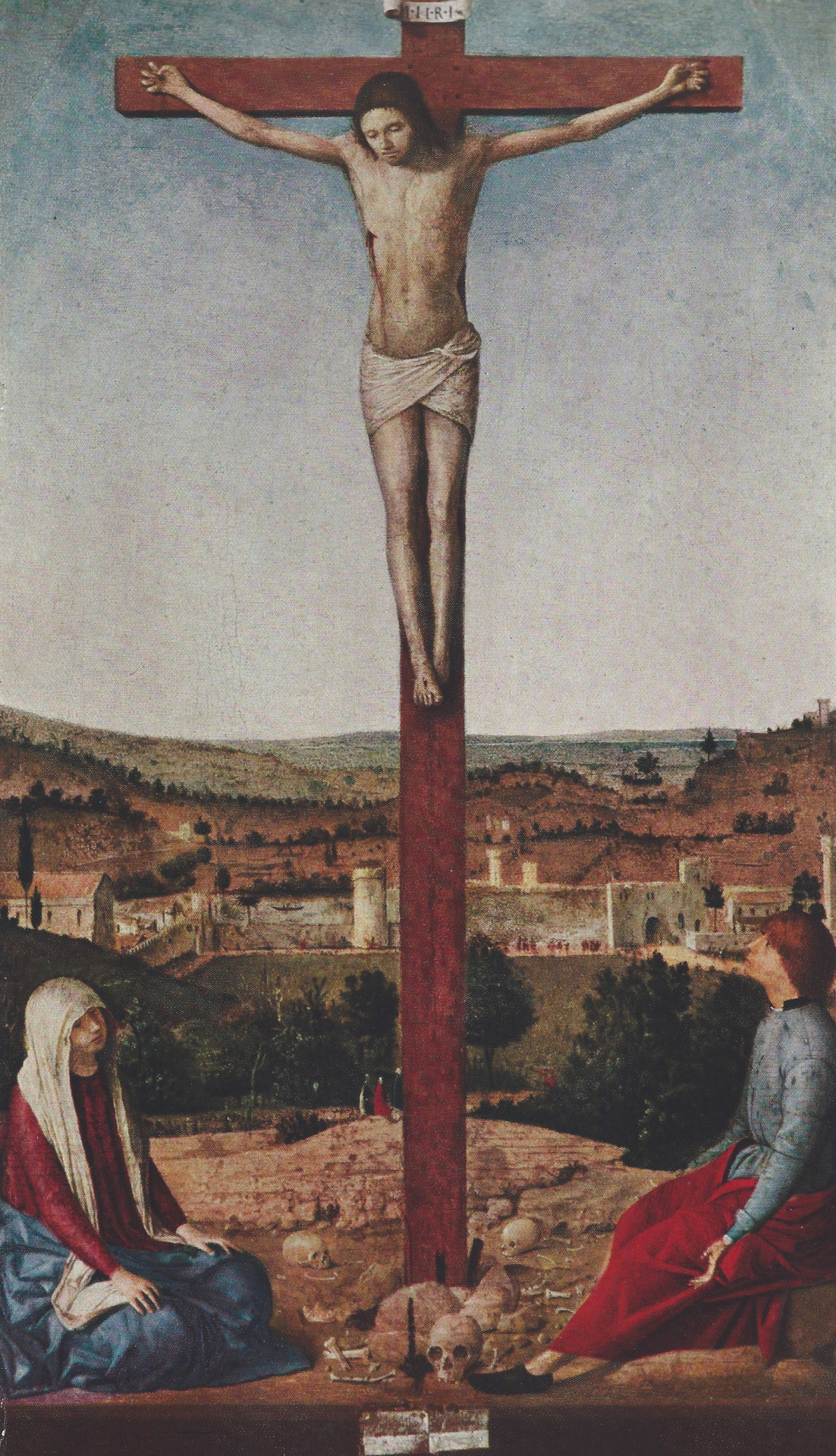

Antonello’s vision is not an historical one; we are not made aware of Greek Sicily, or Roman or Arab or Norman, but of the island in his own day. It is a vision seemingly placid to such an extent that as a backdrop to the violence of the Crucifixion it anchors that world-changing event in a far taller and more timeless world. In the little panel (fig. 2) at the London National Gallery, the composition actually has the form of an anchor, the Cross dropping from the top of the sky to embed itself in the contemplation of the two flanking witnesses. What has happened is absorbed into the immense quietness of the landscape: earth, sea, sky, air.

fig. 2

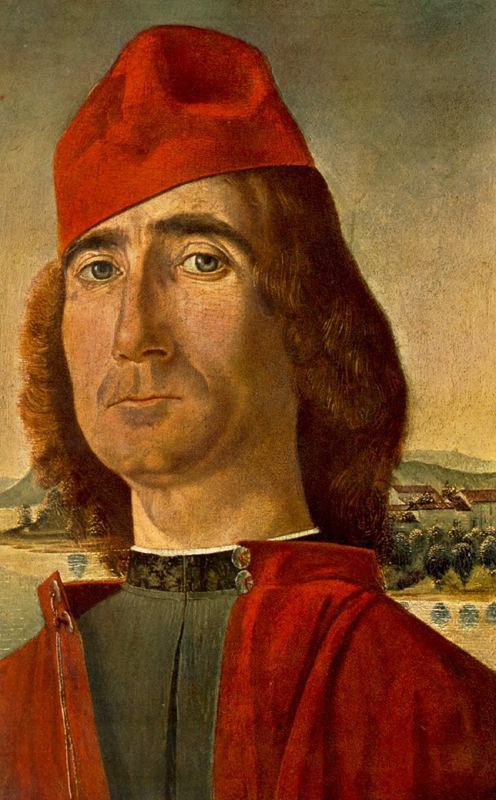

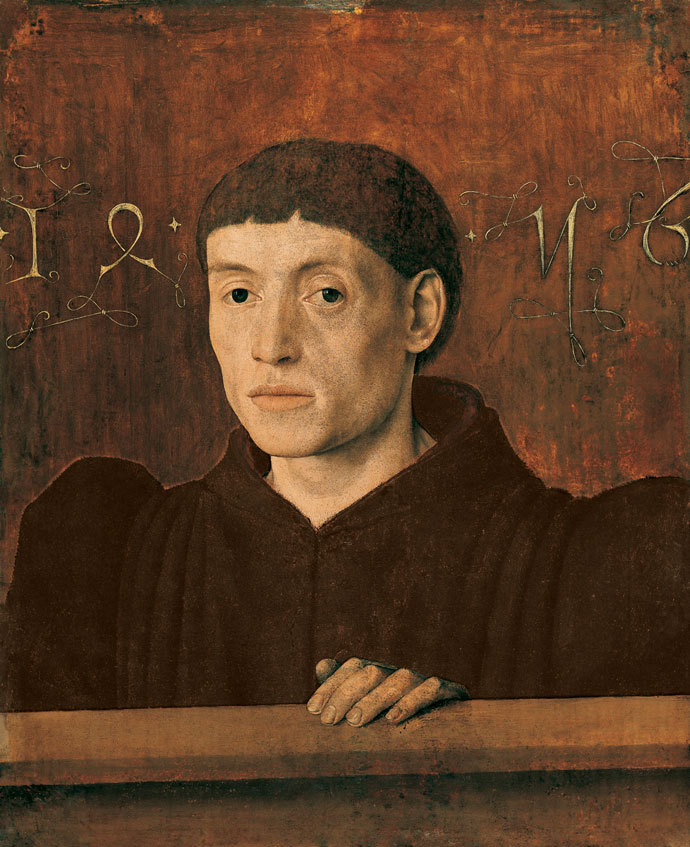

We see this in other pictures. The portraits inhabit the cool, enclosing dark of a hot country. Here are some of them.

fig. 3

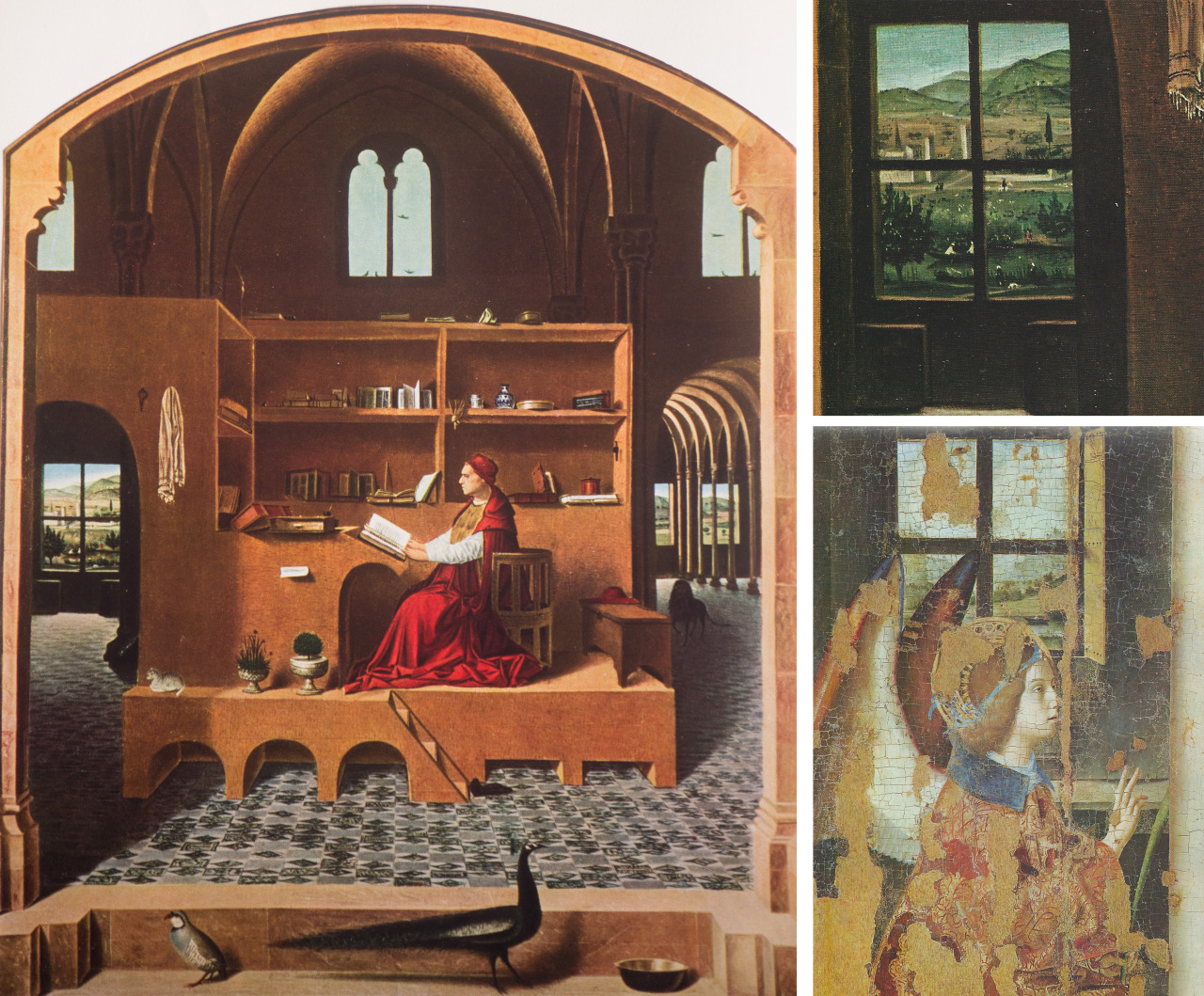

However, his religious scenes are set in the land or in interiors that are open to it, have windows onto it and are ventilated in their spaces by the same air that flows over hills and water. Such pervasive quiet will not disturb Jerome in his alcove, nor stir the wings of an angel, for all the momentous news.

fig. 4

To link Antonello with Van Eyck is to link two artists who are essentially miniaturists in their practice - they use their finest brushes to touch in each dot of stubble on a chin as they would, if they could, every leaf on a tree - but in both cases the clarity of record is at the service of a large, comprehensive and fundamentally spiritual vision. That combination saves the minutiae from being fussy or distracting; we can delight in each particular but it is the delight of discovery after, not before, we have succumbed to the serenity in which that detail is subsumed. Antonello’s miniaturist refinement has, thus, a calming effect.

If I start with this sketch of a critical appreciation, it is because I think it important for connoisseurs to be reminding themselves and others of what is most characteristic and essential in the artist on whom they are focusing. It must be clear by now that at a practical level connoisseurship is either adding or subtracting, either attributing something to an artist or removing from his work something better placed in another’s. I am hard put to say which is more satisfying. It is easy to feel the reward of adding some new and unrecognised work to the tally of what survives of this artist or that; but it is satisfying in another way to remove what is inappropriate, unlike and perhaps unworthy, and by so doing make what is left more coherent, more convincing. I love Antonello da Messina, and my affection makes me want him pure, not alloyed with metal even a little baser.

Urged by this desire I turn to a group of paintings all or some of which are regularly attributed to Antonello but should, I think, be redirected to a lesser contemporary. We can begin with a big, tall painting, a Madonna del Rosario, appropriately at Messina yet clearly not by Antonello da Messina and never attributed to him, only to a ‘pittore quattrocentesca’ (fig. 5).

fig. 5

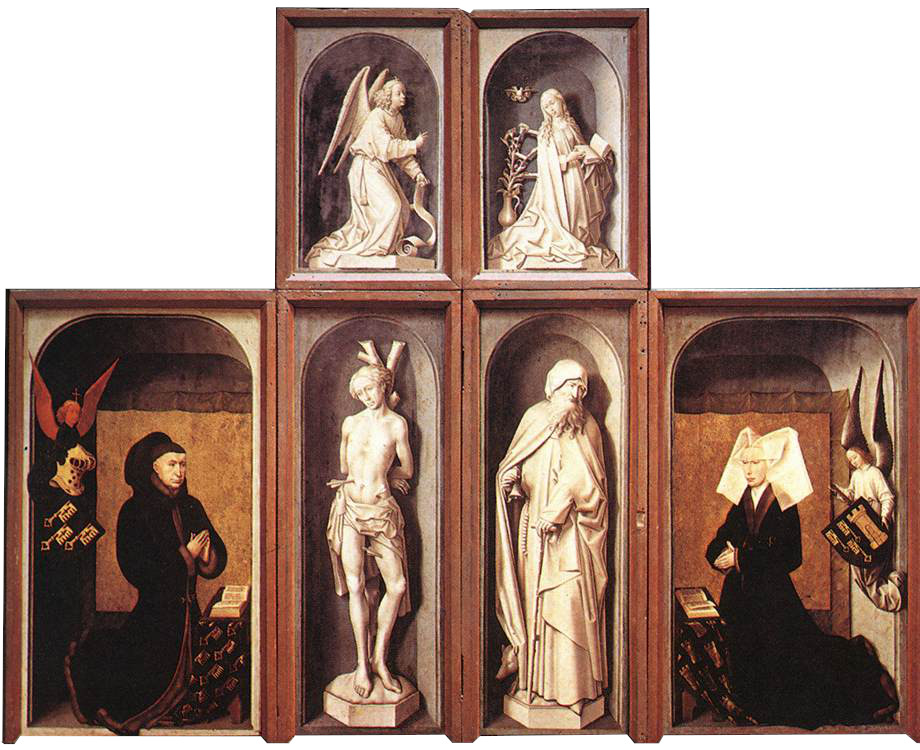

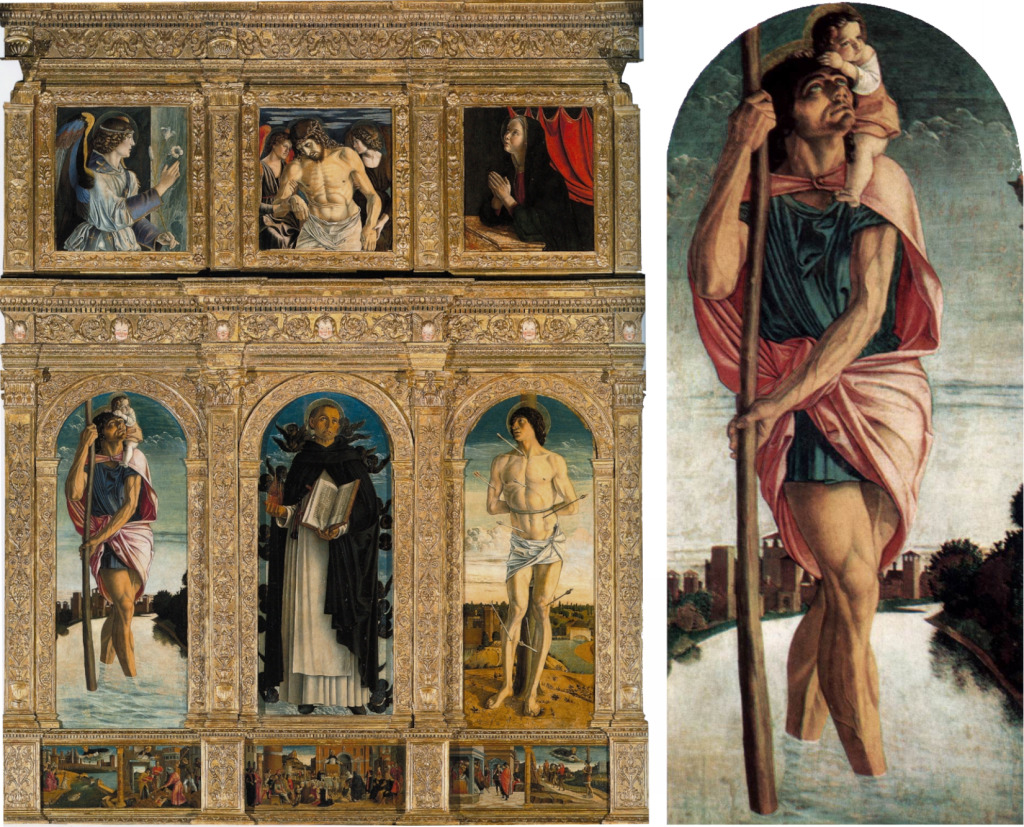

At the top and bottom of this picture are angels: crowning the Virgin and Child above, holding a ribboned inscription below. A certain coarseness in their faces and in the folds of their draperies, together with a particular shade of pink used in those draperies, are all features present in another work at the Messina Museo, the Polyptych of St Gregory which contains among its panels this Virgin and Child.

fig. 6

fig. 7

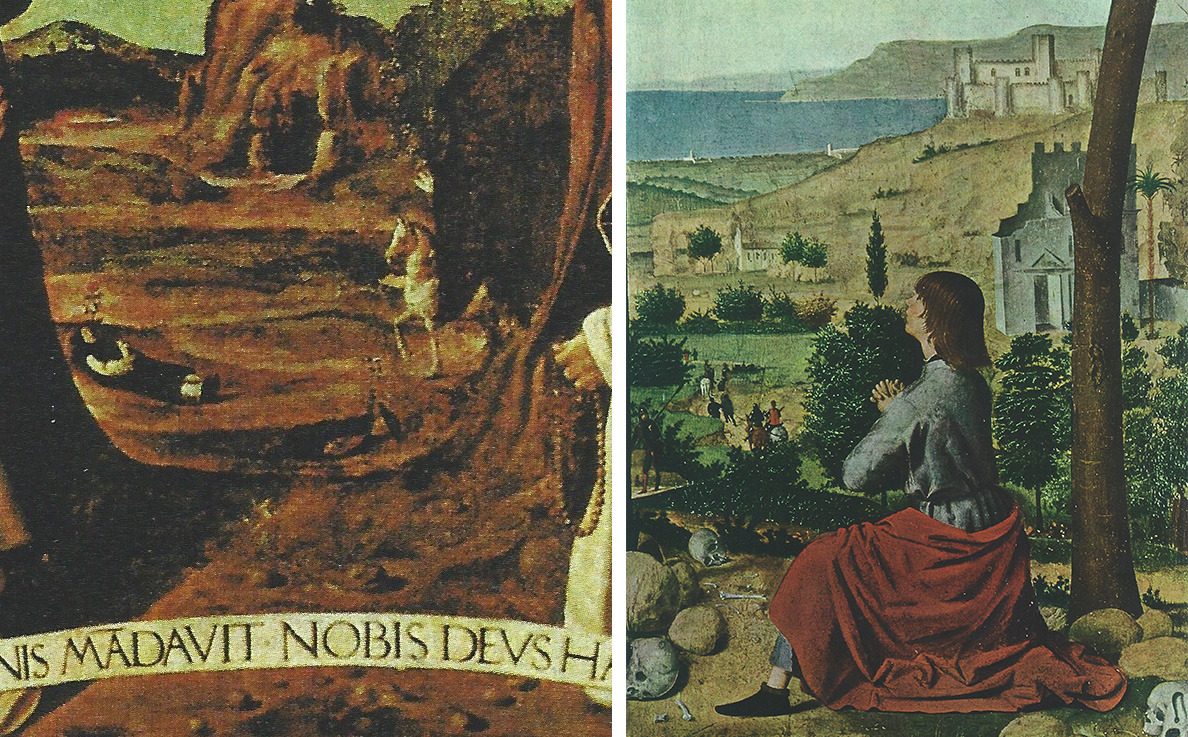

The Polyptych of St Gregory usually does get attributed to Antonello, but I would exclude all of it from his oeuvre and give it instead to this 'Rosario’ master whose facial types, drapery folds and palette are all different from, and noticeably cruder than, Antonello’s. If we turn back to the Madonna del Rosario, we see, beneath the cushion of cloud supporting the Madonna, a vista into a rocky landscape that is a medley of rich autumnal browns.

fig. 8

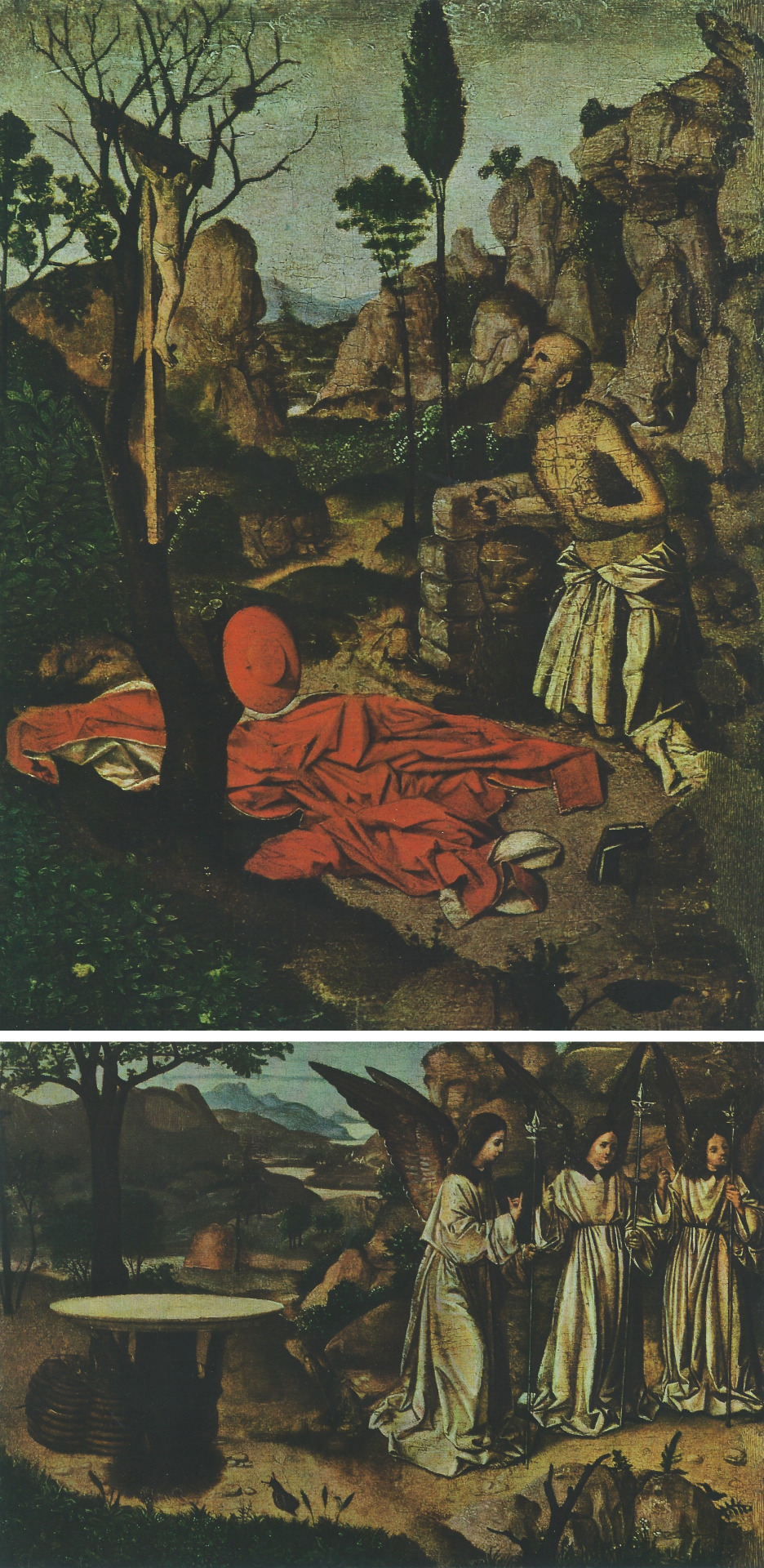

This heavy brown mantling of the landscape, spreading up and out into the figures, seems very far from the early-summer lightness in Antonello’s palette of sandy ochres, greens, yellows, blues. We can see it again, this heavy brown landscape combined with heavy brown folds of drapery, in two other works regularly thought of as 'Early Antonello’, a St Jerome in the Desert and a Three Angels.

fig. 9

I would exclude these also, along with the St Gregory, St Jerome, and St Augustine panels at the National Gallery in Palermo and a San Zosimo in the Cathedral treasury at Syracuse.

fig. 10

This is quite a radical clearance which some will question. It is true that Van Gogh in Belgium is very different from Van Gogh in Provence; but Antonello, though he left the island and worked in Naples and Venice, never, I think, left it in spirit but, like an Irish exile remembering Dublin or Connemara, was always visualising his native land, its scenery and its people. Is there any reason to postulate a radical revisioning and change of style of the kind implied if we continue to see all these 'Rosario’ pictures as Antonellos?

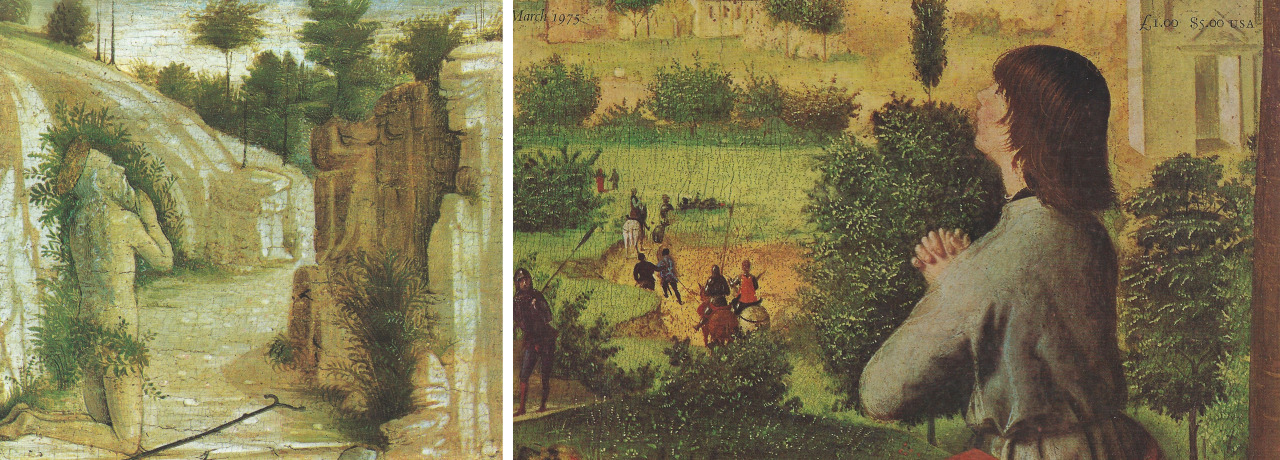

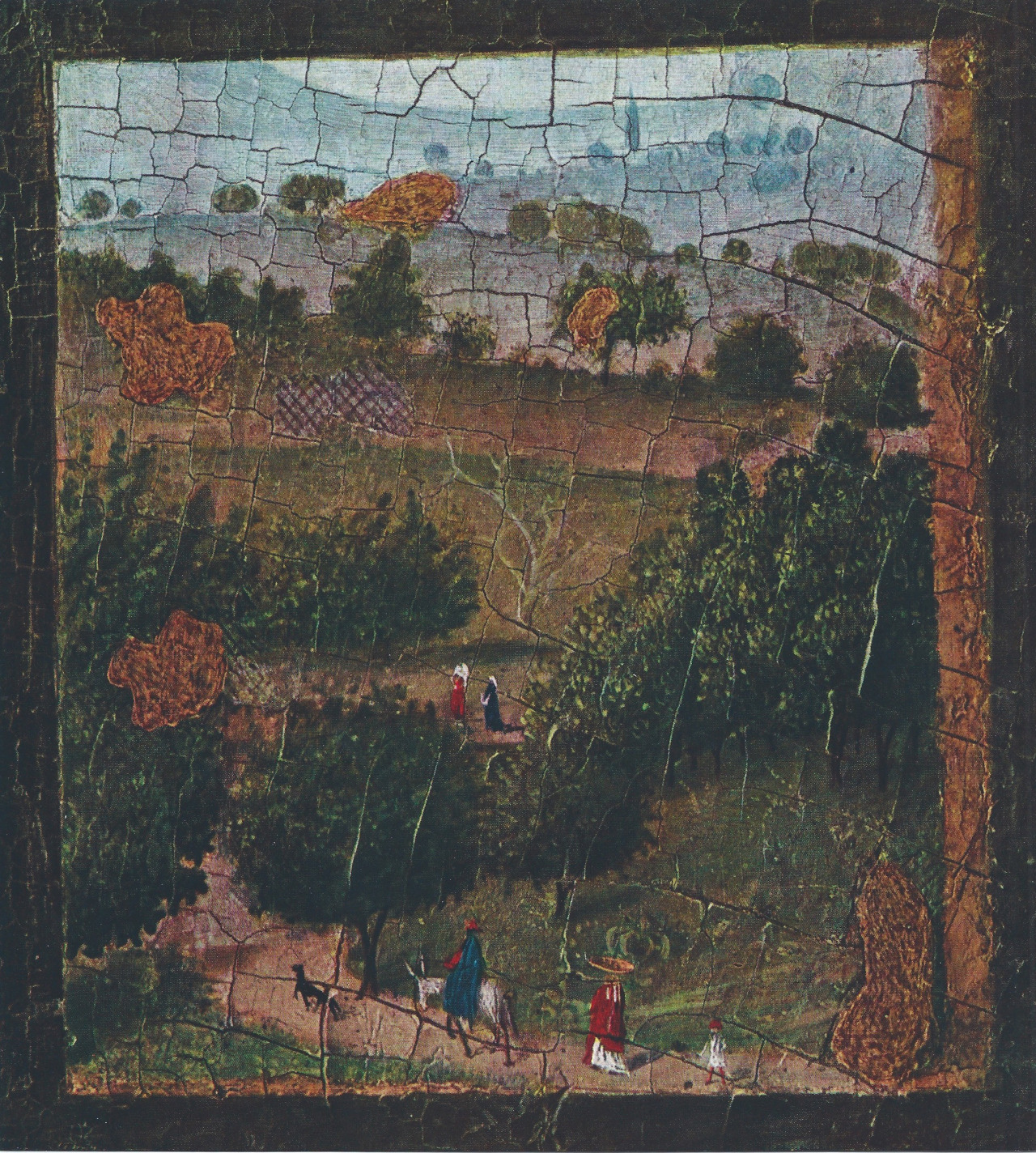

If we are looking to fill the gap left by the ‘Rosario’ paintings with something that might stand for Early Antonello, I would like to suggest a tiny panel (only seven inches square) that is probably in some private collection after passing through a London dealer’s hands in 1979.

fig. 11

Described then as a product of the 'School of Verona’, it shows an old bearded Saint, Onophrius, wearing only a ring of foliage about his loins, kneeling in prayer in a rocky defile scattered here and there with trees. This has the right sandy-green palette and miniaturist brush-tip touch, as we can see if we set it beside the obviously more mature Triple Crucifixion panel in Antwerp’s Musée des Beaux-Arts.

fig. 12

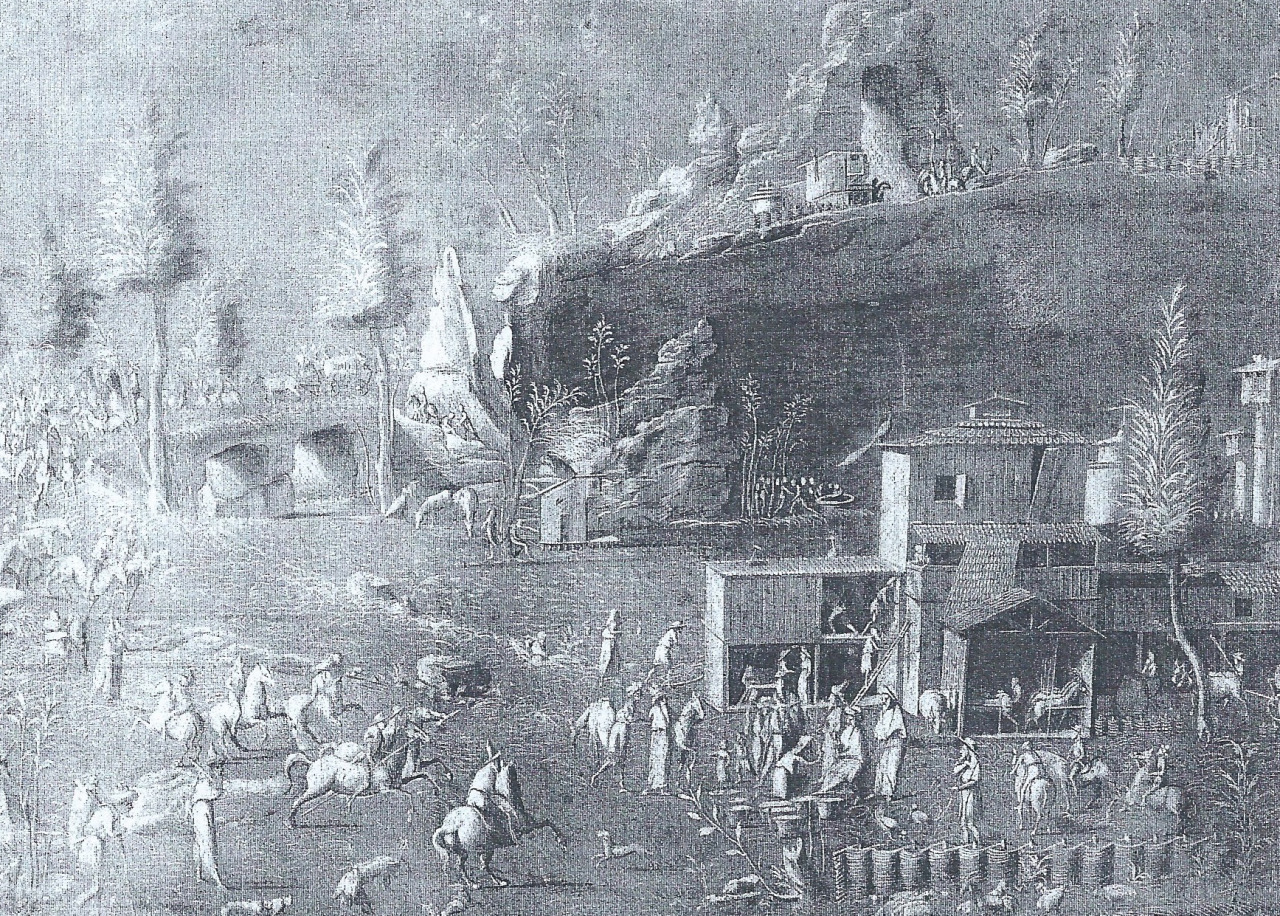

If I study more closely the landscape in that Antwerp picture - so beautifully and lovingly painted that it is the purest pleasure to wander in it - I am very tempted to ascribe to Antonello a remarkable sheet in the Print Room at Dresden (fig. 13).

fig. 13

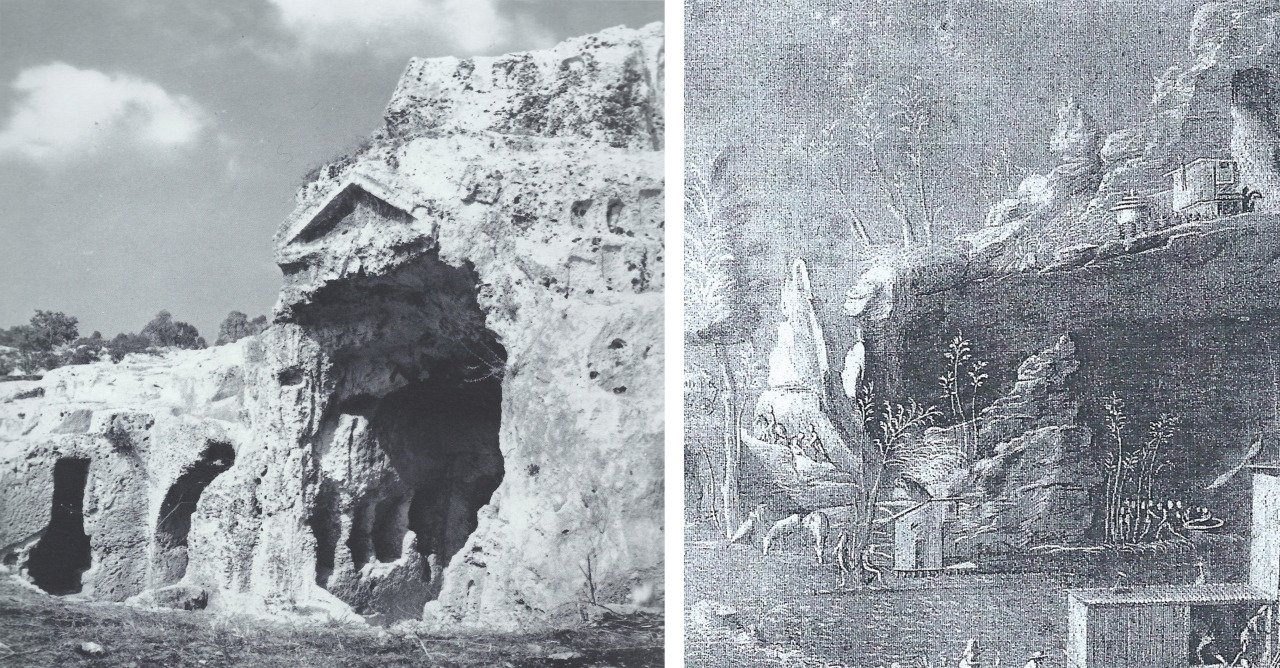

This has the look of a very old drawing made by a man with Antonello’s miniaturist tendency, yet it has a comprehensive grandeur too, combining trees, buildings, a bridge, a mountain and a cave (reminding one a little of the rocky surroundings of Groticelli necropolis or Grotto of the Cordwainers at Syracuse) with all manner of human activity.

fig. 14

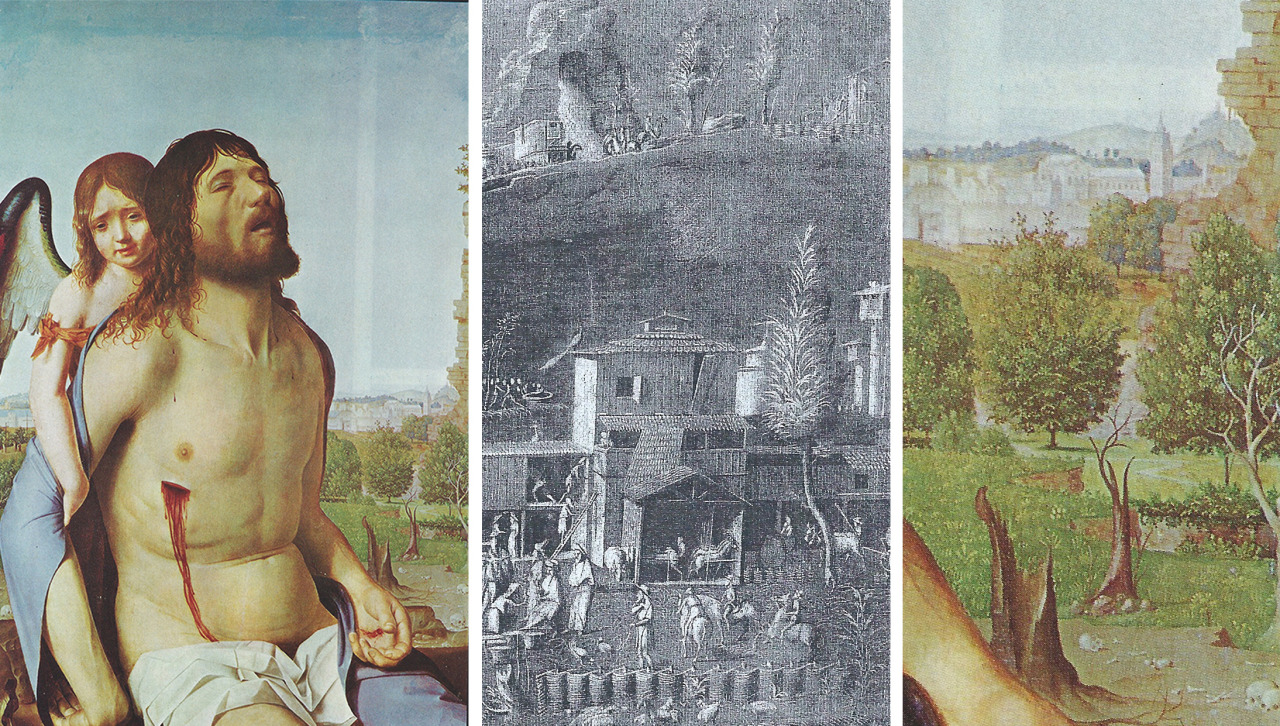

The treatment of the trees, with their feathered sprays of foliage and slender willowy boles, is sufficiently close to what we find in the landscapes of his paintings.

fig. 15

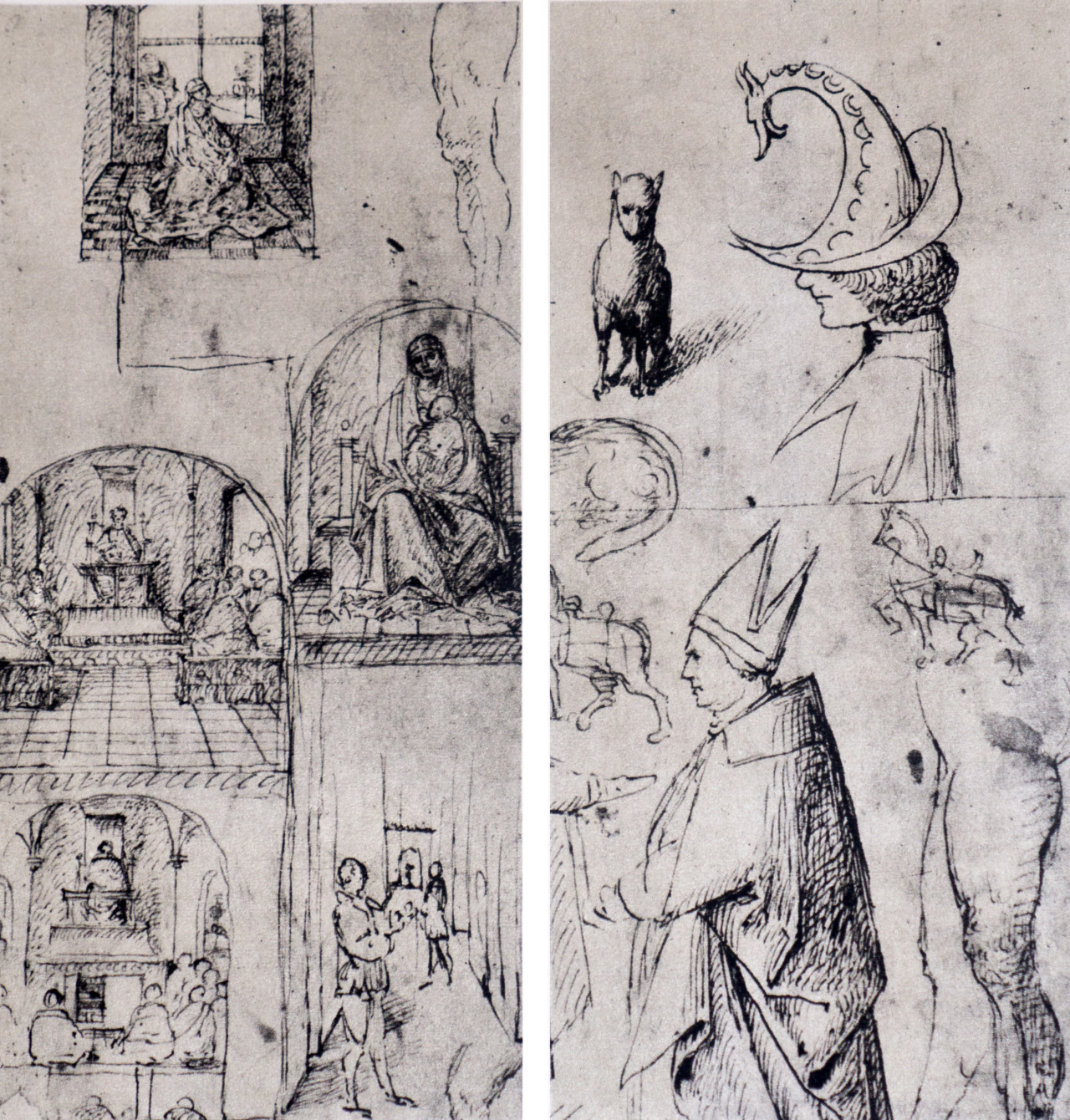

The British Museum drawings so often included in studies of Antonello can be dismissed, I hope, on the grounds of both insufficient likeness and poor quality (sketchy, ill-drawn - look at the legs - and lacking in volume) that these can be dismissed as Antonellos; drawings by someone of his stature and refinement have to be very much better than this.

fig.16

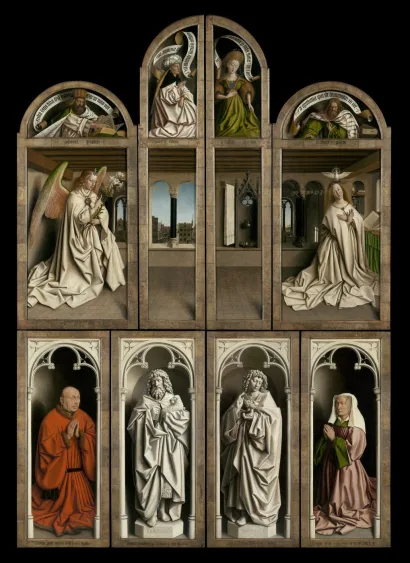

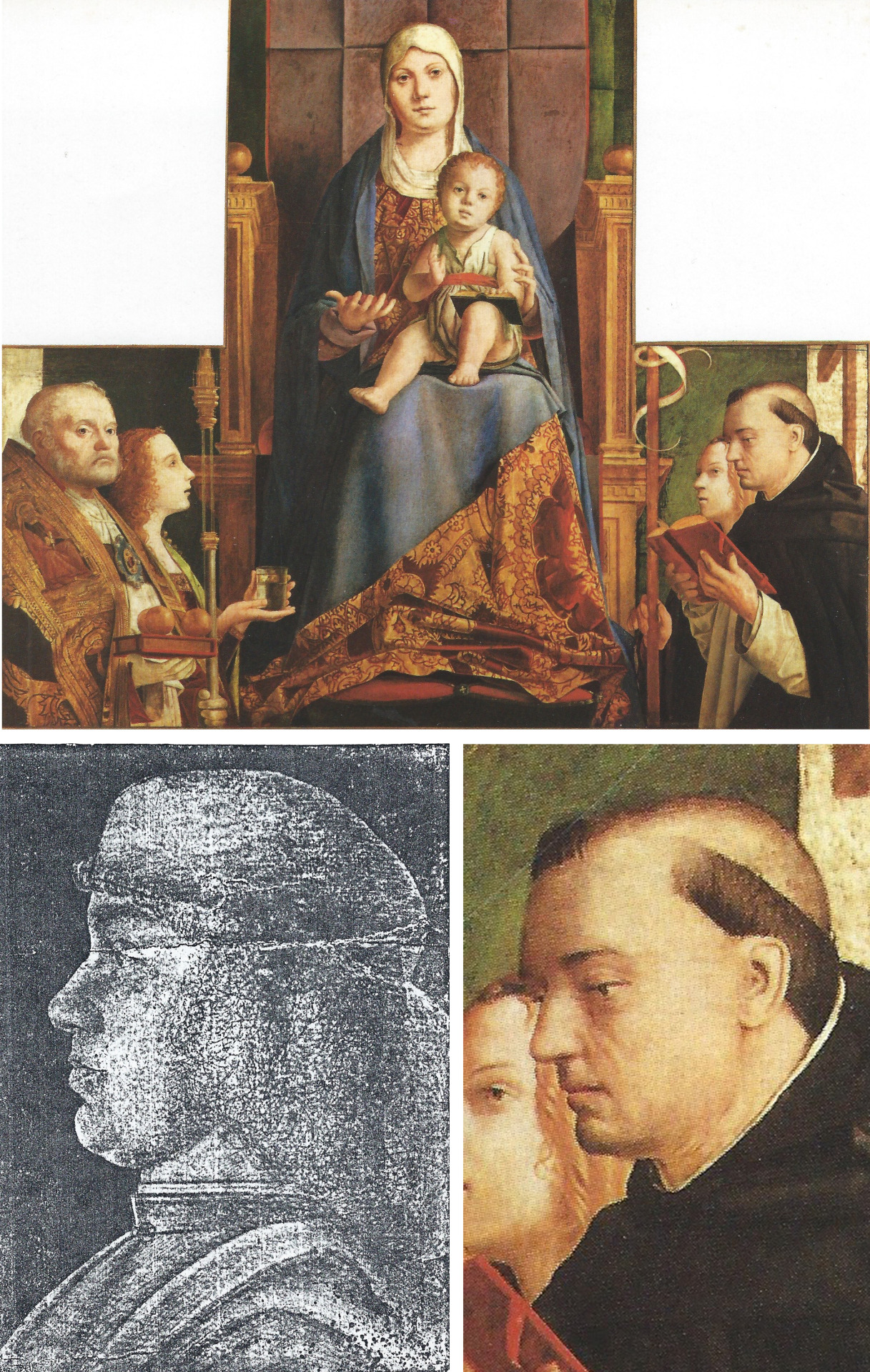

However, there are two candidates from elsewhere that are worthy of him and worth consideration, both of them of a male head. The Berlin drawing (fig. 17b) compares best with the profile of St Dominic in the Altarpiece of San Cassiano at Vienna.

fig. 17

The other, in the Israel Museum at Jerusalem, displays so much of that pure-line clarity in the delineation of eyes and brows and lips which is characteristic and beautiful in Antonello’s painted faces that I was long inclined to attribute it to him. I am not so sure now; the mouth seems too short. If it is by the Rosario Master, as I suspect, or some other, all one can say is that it could not have been drawn without Antonello’s example.

fig. 18

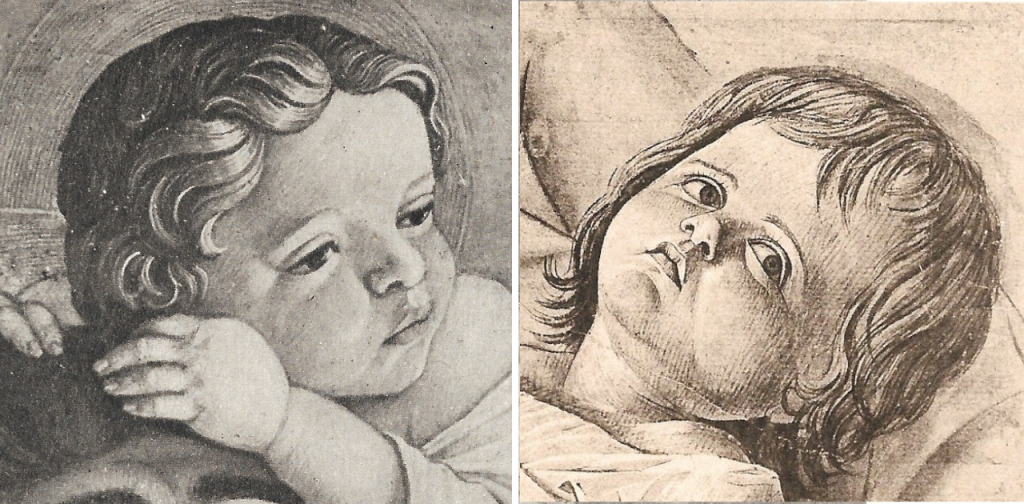

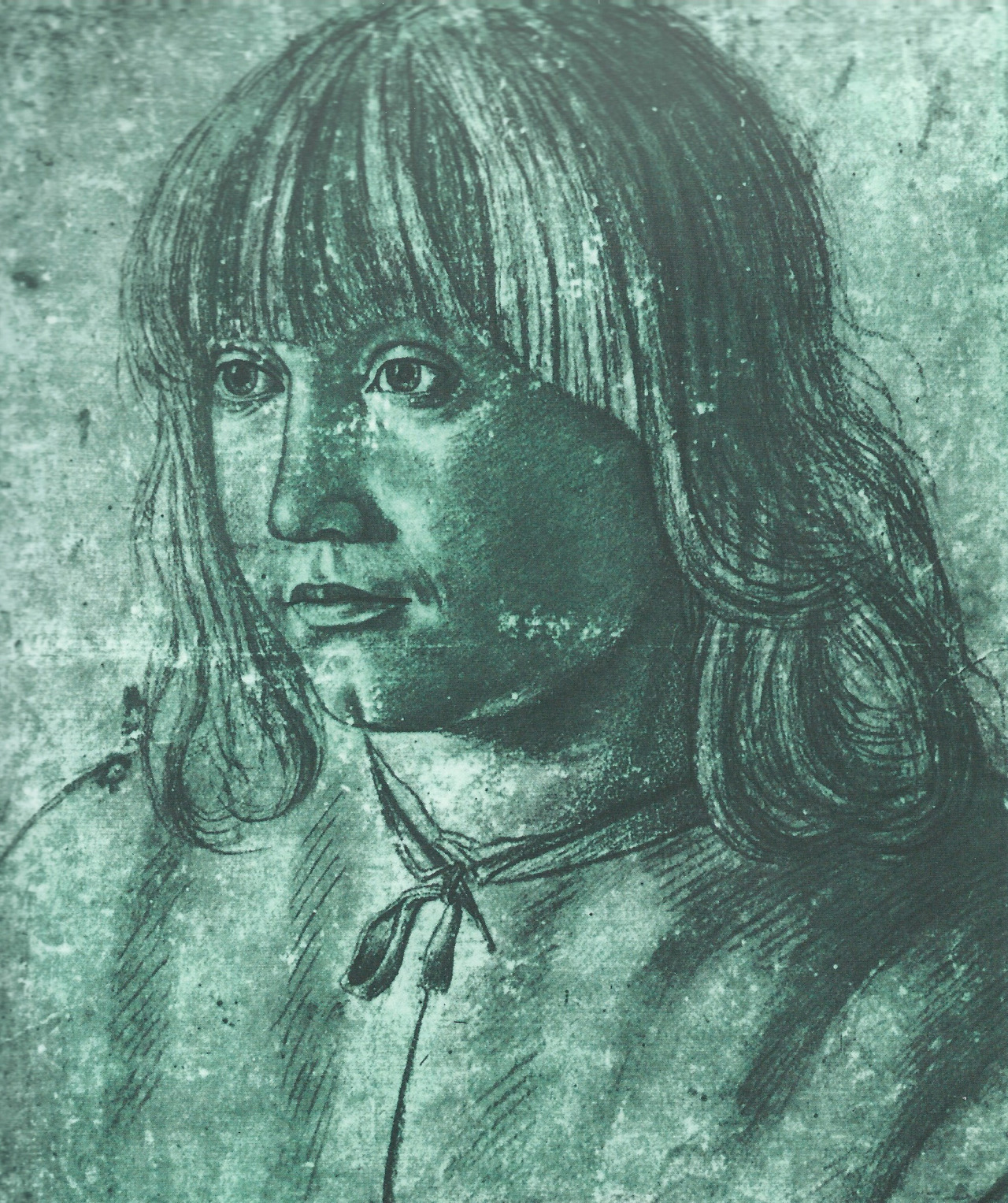

Many studies of the artist and many anthologies of drawings have included one of a young boy, done in charcoal on green paper (figure. 19), in the Albertina collection at Vienna.

fig. 19

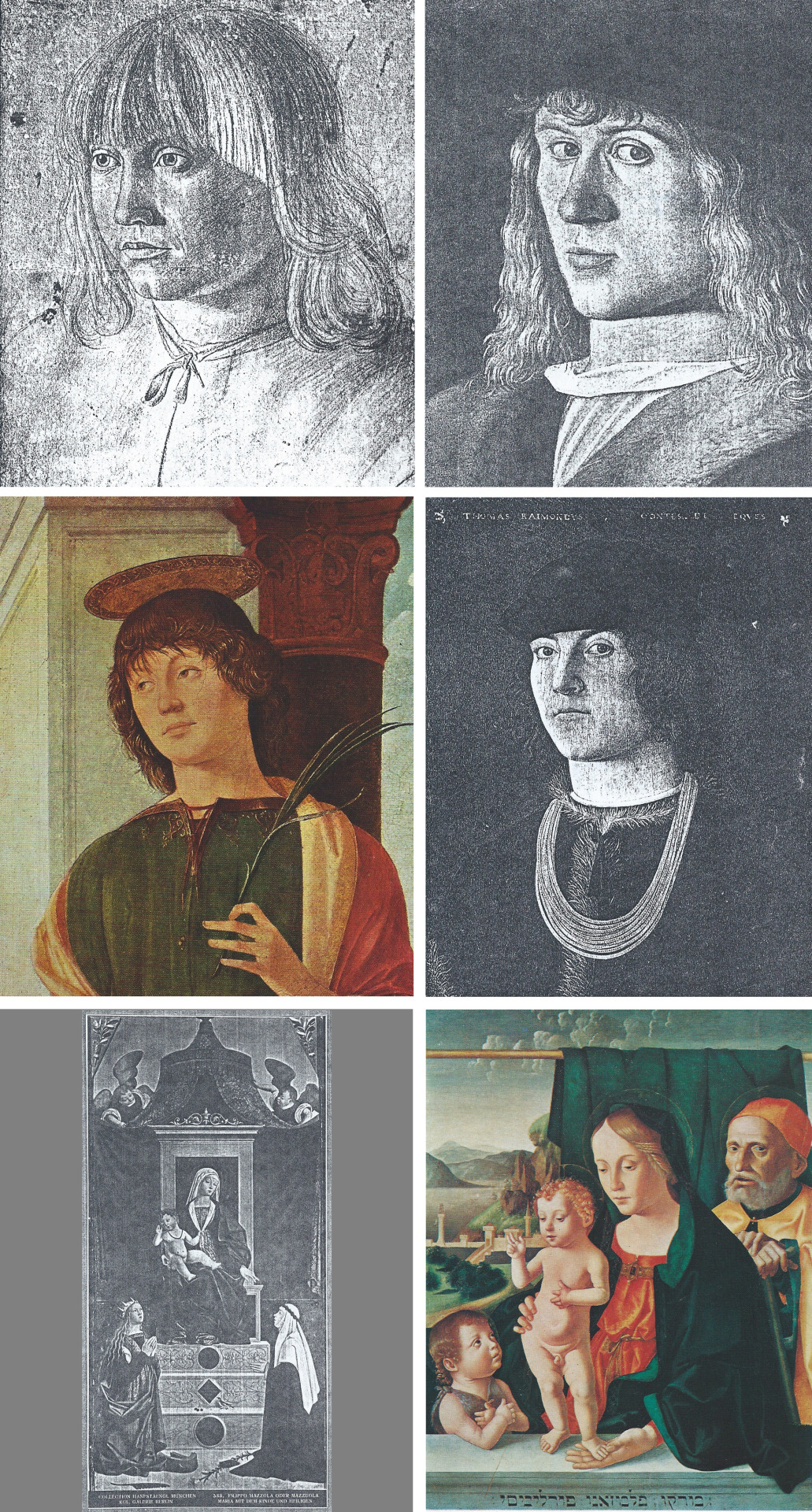

This is a very appealing drawing but it is far more likely to be by a North Italian painter as I can briefly illustrate in the comparisons below (fig. 20). The features to note are the shape of the eyes, especially towards the nose; the modelling of the nose and that vague but vital indicator, ‘expression’.

fig. 20

Here, for the time being, I will leave the connoisseurship trail, but not cease to hope that I or others can discover further connections with the work of an artist so refined in sensibility, so mysterious in perfection, and so patently beautiful. No painter since has ever captured as well as he did the quietness of the land and the continuity within it of ordinary life that has always been the backdrop to that island’s recurring violence. 'Sicilian Vespers’ sound so peaceful, like the whispering of wind, but they were not.

fig. 21

Footnotes:

fig. 1

Antonello Da Messina, Triple Crucifixion, Panel Brukenthalisches Museum, Sibiu, Romania.

fig. 2

Antonello Da Messina, The Crucifixion, dated 1475, Panel 41.9x25.4cm, National Gallery London (NG1166)

fig. 3

Antonello Portraits

a) Portrait of a Man (‘Il Condottiere’), Louvre Paris.

b) Portrait of a Man, dated 1476, Museo Civico, Turin.

c) Portrait of a Man, Museo Mandralisca, Cefalu, Sicily

d) Portrait of a Man, National Gallery, London (NG1141).

e) Portrait of a Man, Thyssen Bornemisza Museum, Madrid.

f) Portrait of a Man, Villa Borghese

fig. 4

a) Antonello Da Messina, St Jerome in his Study (45.7x36.2cm), National Gallery London, (NG1418).

b) Window detail of fig. 4a.

c) Window detail of Annunciation panel, Museo Nazionale, Syracuse, Sicily.

fig. 5

Madonna del Rosario, Anonymous 15th Century, Museo Nazionale Messina.

fig. 6

Triptych of San Gregorio, attributed to Antonello, here to Rosario master, Museo Nazionale Messina.

fig. 7

a) Detail of Angel in fig. 5.

b) Detail of Madonna and Child in fig. 6.

c) Detail of Angel in fig. 5

fig. 8

a) Detail of landscape in fig. 5

b) Detail of landscape in Antonello’s Triple Crucifixion, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Antwerp.

fig. 9

a) St Jerome in the desert, panel attributed to Antonello, Museo Nazionale, Reggio Calabria, Italy

b) Three Angels, Panel attributed to Antonello, Museo Nazionale, Reggio Calabria, Italy

fig. 10

Three panels attributed to Antonello. Museo Nazionale Palermo

a) St Gregory

b) St Augustine

c) St Jerome

d) San Zosimo, Tesoro della Cathedrale, Syracuse, Sicily.

fig. 11

St Onophrius in a Rocky Landscape, here suggested as early Antonello, panel 17.2x19cm, sold as School of Verona. Christopher Gibbs (London dealer) 1979 (Reproduced in Apollo, March 1979)

fig. 12

a) fig. 11

b) fig. 8b

fig. 13

Drawing, Figures in a landscape, here attributed to Antonello, Kupferstichkabinett, Dresden.

fig. 14

a) Photo of Groticelli necropolis (Grotto of the Cordwainers), Syracuse.

b) Detail of fig. 13.

fig. 15

a) Antonello, Christ supported by an Angel, Panel 74x51cm, Prado Madrid.

b) Detail of fig. 13

c) Detail of fig. 15a

fig. 16

a)&b) Drawings, sheet of sketches, recto and verso, often attributed to Antonello, Pen and brown ink, Popham and Pouncey Cat. 1950. No.333, Print room, British Museum, London.

fig. 17

a) Altarpiece of San Cassiano, incomplete. Madonna and Child with Saints (Nicolas of Bari and Anastasia, left; Ursula and Dominic, right), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

b) Drawing, Profile of a Man, Antonello da Messina?, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

c) Detail of fig. 17a

fig. 18

a) Drawing, head of a Man wearing Hat, ‘North-Italian School’, Watercolour on parchment, (31.2x27.1cm), Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

b) Detail of Head of St Gregory, panel, Galleria Nazionale Palermo.

c) Head of St Benedict, panel, Galleria Nazionale Messina.

d) Head of Virgin, from Polyptych of St Gregory, Museo Nazionale, Messina

fig. 19

Drawing, head of Young Man, Charcoal on green paper, often attributed to Antonello, here to a North Italian artist, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

fig. 20

a) Fig. 19

b) Detail of Portrait of a Man ‘Venetian School’, National Gallery of Art Washington (Widener Collection).

c) Detail of St John the Evangelist. Panel Accademia, Carrara, Bergamo.

d) Portrait of a Man (Thomas Raimondus), Panel 40x30cm, North Italian School, Sale Petit, Paris, 2/6/1913

e) Madonna and Child enthroned with Saints, dated 1502, Staatliche Galerie, Berlin.

f) Virgin and Child with Joseph and infant St John, Panel, Phoenix Art Museum, Arizona.

fig. 21

Landscape from Antonello da Messina’s Annunciation, Museo Regionale, Syracuse, Sicily.