Plessy v. Ferguson: An Excerpt from Firsthand Louisiana

Discover the history of the Pelican State through the eyes of the people who lived it and shaped its course. In Firsthand Louisiana: Primary Sources in the History of the State, historians Janet Allured, John Keeling, and Michael Martin have compiled dozens of important, interesting, devastating, and even entertaining firsthand accounts cover Louisiana’s history along with questions for further analysis and discussion. Below is an excerpt concerning the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision and its impact on Louisiana and the nation as a whole.

1896: Plessy v. Ferguson

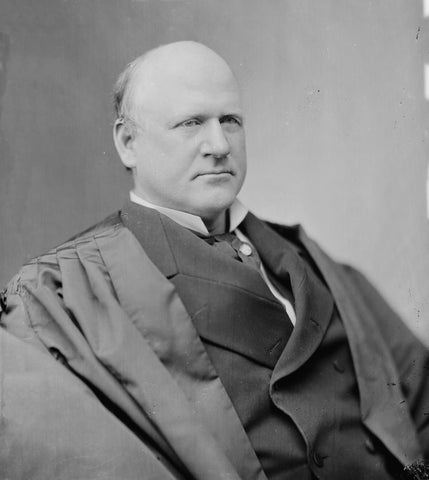

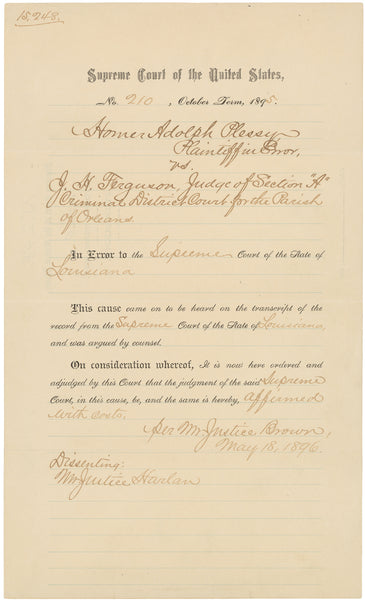

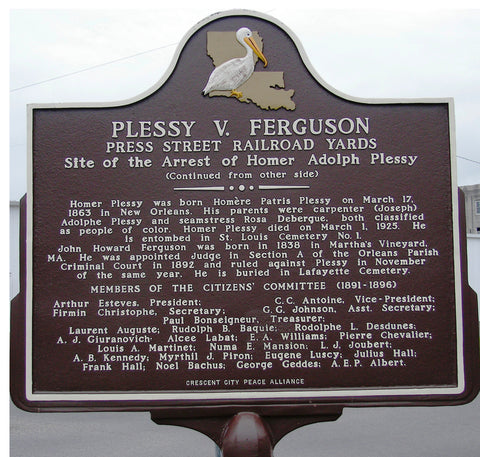

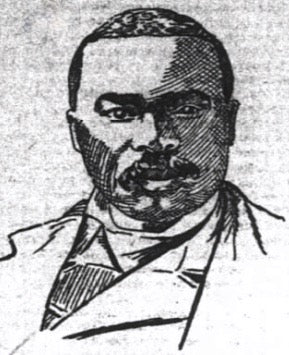

The most important United States Supreme Court case to originate in Louisiana is Plessy v. Ferguson, which in 1896 affirmed the constitutionality of southern segregation laws. In 1890 the Louisiana legislature passed the state’s first segregation bill, the Separate Car Act, which required that railroads provide separate cars for white and black passengers. As a state senator from St. John the Baptist Parish, Henry Demas was one of four remaining African American Republicans in that chamber. In response to the act, leading members of the Afro-Creole community in New Orleans formed the Comité des Citoyens (Citizens Committee) to challenge the legality of the act. On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy bought a first-class train ticket from New Orleans to Covington and boarded the white passenger car. A private detective hired by the committee ensured that the conductor had him arrested for violating the Separate Car Act, and the test case began. After losing both in a local court and the Louisiana Supreme Court, the case was appealed to the US Supreme Court. In a 7–1 decision, the Court upheld the constitutionality of the Separate Car Act, asserting, among other points, that it was a reasonable exercise of the state’s police power to maintain the health, safety, and morals of its citizens. Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan, however, saw through the reasoning behind the law and the majority opinion, and declared in the most famous dissenting opinion in the history of the Court that the decision established second-class citizenship for African Americans in the South. Through the “separate but equal” rule, that accommodations for each race had to be roughly the same in quality, Jim Crow laws came to dominate southern race relations until overturned fifty-eight years later by Brown v. Board of Education.

The most important United States Supreme Court case to originate in Louisiana is Plessy v. Ferguson, which in 1896 affirmed the constitutionality of southern segregation laws. In 1890 the Louisiana legislature passed the state’s first segregation bill, the Separate Car Act, which required that railroads provide separate cars for white and black passengers. As a state senator from St. John the Baptist Parish, Henry Demas was one of four remaining African American Republicans in that chamber. In response to the act, leading members of the Afro-Creole community in New Orleans formed the Comité des Citoyens (Citizens Committee) to challenge the legality of the act. On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy bought a first-class train ticket from New Orleans to Covington and boarded the white passenger car. A private detective hired by the committee ensured that the conductor had him arrested for violating the Separate Car Act, and the test case began. After losing both in a local court and the Louisiana Supreme Court, the case was appealed to the US Supreme Court. In a 7–1 decision, the Court upheld the constitutionality of the Separate Car Act, asserting, among other points, that it was a reasonable exercise of the state’s police power to maintain the health, safety, and morals of its citizens. Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan, however, saw through the reasoning behind the law and the majority opinion, and declared in the most famous dissenting opinion in the history of the Court that the decision established second-class citizenship for African Americans in the South. Through the “separate but equal” rule, that accommodations for each race had to be roughly the same in quality, Jim Crow laws came to dominate southern race relations until overturned fifty-eight years later by Brown v. Board of Education.

“The Separate Car Bill,” Daily Times-Democrat, July 8, 1890

The Southern whites, in no spirit of hostility to the Negroes, have insisted that the two races shall live separate and distinct from each other in all things, with separate schools, separate hotels and separate cars. They would rise to-morrow against the proposition to educate the white and black children together; and they resist any intercourse in theatre, hotel or elsewhere that will bring the race into anything like social intercourse. The quarter of a century that has passed since the war has not diminished in the slightest degree the determination of the whites to prevent any such dangerous doctrine as social equality, even in the mildest form. They give the Negroes schools; but these must be separate; and the cars also should be separate, in order to keep the races as far apart as ever. We cannot afford to surrender anything in this case.The law—private not public—which prohibits the Negroes from occupying the same place in a hotel, restaurant or theatre as the whites, should prevail as to cars also. As a matter of fact, one is thrown in much closer communication in the car with one’s traveling companions than in the theatre or restaurant with one’s neighbors. Whites and blacks may there be crowded together, squeezed close to each other in the same seats, using the same conveniences, and to all intents and purposes in social intercourse. A man that would be horrified at the idea of his wife or daughter seated by the side of a burly Negro in the parlor of a hotel or at a restaurant cannot see her occupying a crowded seat in a car next to a Negro without the same feeling of disgust.The Louisiana Senate ought to step in and prevent this indignity to white women of Louisiana, as the Legislatures of other Southern States have done.It is not proposed to refuse the Negroes any right to which they are entitled. They are to have the same kind of cars, but separate ones. The man who believes that the white race should be kept pure from African taint will vote against that commingling of the races inevitable in a “mixed car” and which must have bad results. . . .

Speech of Hon. Henry Demas, on the Separate Car Bill, Delivered in the Senate, at Baton Rouge, La., July 8, 1890

Mr. President, the bill which we now have under consideration is one that, in my opinion, has not been properly framed. This is obvious to all who will read it carefully over. It places the entire Negro race upon one common level and makes no distinction between the ignorant and the illiterate, and those who, by education, refinement and culture, have raised themselves above the standard of their race. This bill, also, Mr. President, panders to class legislation,—and, by two sharply drawing the line between the races, destroys that harmony which should exist at all times between them. It is an undeserved stigma upon the Negro. The prosperity of Louisiana depends in a great measure upon his industry and toil. . . .

Mr. President, this State is peopled by a far larger number of cultured and wealthy colored people than is conjectured, and, owing to the intermingling of the raises, it is not frequently a difficult matter to determine,—from a standpoint of color,—the white from the Negro. Would it not be unjust, I ask, to relegate this class to a coach occupied by those much inferior to them in life, and by thus doing humiliate a people accustomed to better surroundings. It would be forcing them to associate with the worst class of Negro element, and would be an unmerited rebuke upon the colored man of finer sensibilities. . . .

Mr. President, the occurrences of the past by which we should be guided, I believe, and which should prove a forecast for the future, show that the Negro is coming to the front rapidly. Twnety-five years ago when the yoke of slavery was removed from him, the Negro was an ignorant, illiterate and unenlightened man; with praiseworthy ambition, he resolutely set to work to ameliorate his condition and, if coming events cast their shadows before, the next decade will witness a remarkable change for the better in his moral and mental condition. He may be trampled upon by arbitrary laws, but his advancement to a higher plan of citizenship and civilization cannot be checked. Persecution cannot down him, and in his invincible march to a better and more elevated goal, his advancement has been steady and continuous.

Mr. President, who are the enemies of the colored people? Is it the educated and refined white? No, it is that class who have no social or moral standing in the community where they live, and therefore they with keen sensibility feel their inferiority, and to acquire cheap notoriety they are willing to resort to any measure, they care not how insignificant, perfidious, or oppressive it may be against the Negro, in order to carry out their unholy and hellish designs. . . .

Like the Jews we have been driven from our homes and firesides, from our churches and school-houses, [from] our civil and political liberties, and from the elevated avenues of livelihood, and now in order to reach the lowest depth of infamy, in order to surpass all other indignities heaped upon us, you are willing to forget you are men and vote for the passage of this bill.

Mr. President, when this bill shall have passed it is the last indignity left for you to [heap] upon us. You have exhausted every indignity, you have inflicted upon us every oppression known to your race, and we have born it with patience unknown to other races without a single word of resentment, because we desired the security of peace, prosperity and happiness for all. But the time will and must come in our case, as it has in the history of other races, when we will rise and strike, for our liberties, let the chips fly where they may or consequences be what they will.

Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan’s dissent, Plessy v. Ferguson

It was said in argument that the statute of Louisiana does not discriminate against either race but prescribes a rule applicable alike to white and colored citizens. But this argument does not meet the difficulty. Everyone knows that the statue in question had its origin in the purpose, not so much to exclude white persons from railroad cars occupied by blacks, as to exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white persons. Railroad corporations of Louisiana did not make discrimination among whites in the matter of accommodation for travelers. The thing to accomplish was, under the guise of giving equal accommodations for whites and blacks, to compel the latter to keep to themselves while traveling in railroad passenger coaches. No one would be so wanting in candor as to assert the contrary. The fundamental objection, therefore, to the statue is that it interferes with the personal freedom of citizens. . . . If a white man and a black man choose to occupy the same public conveyance on a public highway, it is their right to do so, and no government, proceeding alone on grounds of race, can prevent it without infringing the personal liberty of each. . . .

The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in the view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved. . . .

The arbitrary separation of citizens, on the basis of race, while they are on a public highway, is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution. It cannot be justified upon any legal grounds.

If evils will result from the commingling of the two races upon public highways established for the benefit of all, they will be infinitely less than those that will surely come from state legislation regulating the enjoyment of civil rights upon the basis of race. We boast of the freedom enjoyed by our people above all other peoples. But it is difficult to reconcile that boast with the state of the law which, practically, puts the brand of servitude and degradation upon a large class of our fellow citizens, our equals before the law. The thin disguise of “equal” accommodations for passengers in railroad coaches will not mislead anyone, nor atone for the wrong this day done.

“Equality, But Not Socialism,” Daily Picayune, May 19, 1896

The Louisiana law which requires that the railways operating trains within the limits of the State shall furnish separate but equal accommodations for white and Negro passengers was passed upon in the Supreme Court of the United States, and was yesterday declared to be constitutional.The decision holds that the statute in question does not abridge any of the constitutional privileges and immunities of the plaintiff, because it does not create any inequality between the citizens of the State and the citizens of the United States, or between citizens of different race or color. It provides equal privileges to all on all the railroads engaged in intrastate transit. It does not discriminate unfairly between citizens of the United States or between citizens of the State, of whatever color or race. It was legislation which it was competent for the State to enact as within the police power. The Supreme Court has held that the legislature determines the necessity for, and the courts the proper subject for, the exercise of the police power which extends to the protection of the lives, limbs, health, comfort, morals and quiet of society, private interests being subservient to the public.As there are similar laws in all the States which abut on Louisiana, and, indeed, in most of the Southern States, this regulation for the separation of the races will operate continuously on all lines of Southern railway. Equality of rights does not mean community of rights. The laws must recognize and uphold this distinction; otherwise, if all rights were common as well as equal, there would be practically no such thing as private property, private life, or social distinctions, but all would belong to everybody who might choose to use it.This would be absolute socialism, in which the individual would be extinguished in the vast mass of human being, a condition repugnant to every principle of enlightened democracy.

Text Sources:

- “The Separate Car Bill,” Daily Times-Democrat (New Orleans), July 8, 1890.

- The Crusader (New Orleans), July 19, 1890, Nils R. Douglas papers, 1893– 1967, Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.

- Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

- “Equality, But Not Socialism,” Daily Picayune (New Orleans), May 19, 1896. Library of Congress.

Document Image Source: National Archives, Public Domain