April 24, 2020French photographer and filmmaker Sarah Moon is known for dreamlike images that resemble moments of reverie frozen in time. “For me, photography is pure fiction, even if it comes from life,” Moon has said. “I start from nothing. I make up a story that remains untold, I imagine a situation that doesn’t really exist, I watch out for what I didn’t expect, I wait to see what I can’t remember, I undo what I had put together.”

The fluidity of Moon’s concept is captured in the title of her upcoming retrospective, “PastPresent,” which is slated to run from September 21 to July 4, 2021, at the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris. The exhibition will bring together her elegant and enigmatic fashion and personal photographs, videos and films from the past 50 years. The works are organized in an intuitive, nonchronological, nonlinear manner, mixing eras, techniques and genres. A gallery is also dedicated to the late Robert Delpire (1926–2017), Moon’s companion for some five decades and the visionary publisher and editor who championed such photographers as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Brassaï, William Klein and Robert Frank.

Born in France in 1941 to a Franco-American father and French mother, Moon was raised in England, where she moved at age 10. She began her professional life as a model, posing for such eminent fashion photographers as Guy Bourdin, and first picked up a camera in 1968. She began shooting pictures of her friends, models like herself, as a hobby but soon began a career on the other side of the lens.

Completely self-taught, she displayed a distinctly personal perspective, and her first fashion campaigns, starting in the late 1960s for Biba and then Cacharel, soon acquired cult status. Her images were soft-focus and enigmatic, inspired by the aesthetics of 1920s filmmakers like the Soviet Sergei Eisenstein and Germans G.W. Pabst, Carl Theodor Dreyer and F.W. Murnau.

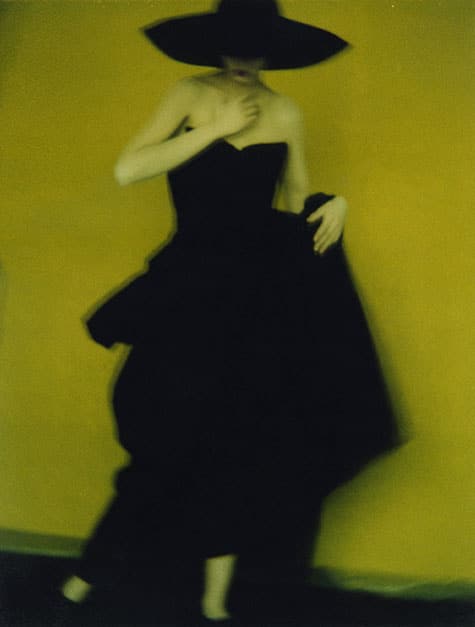

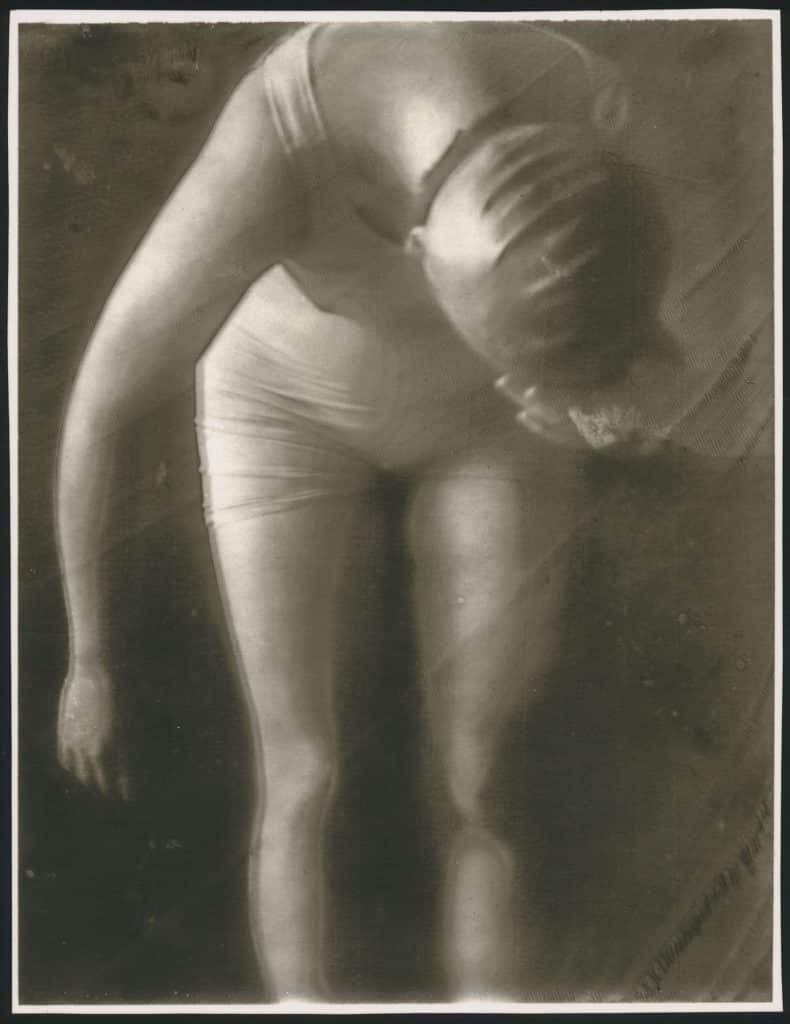

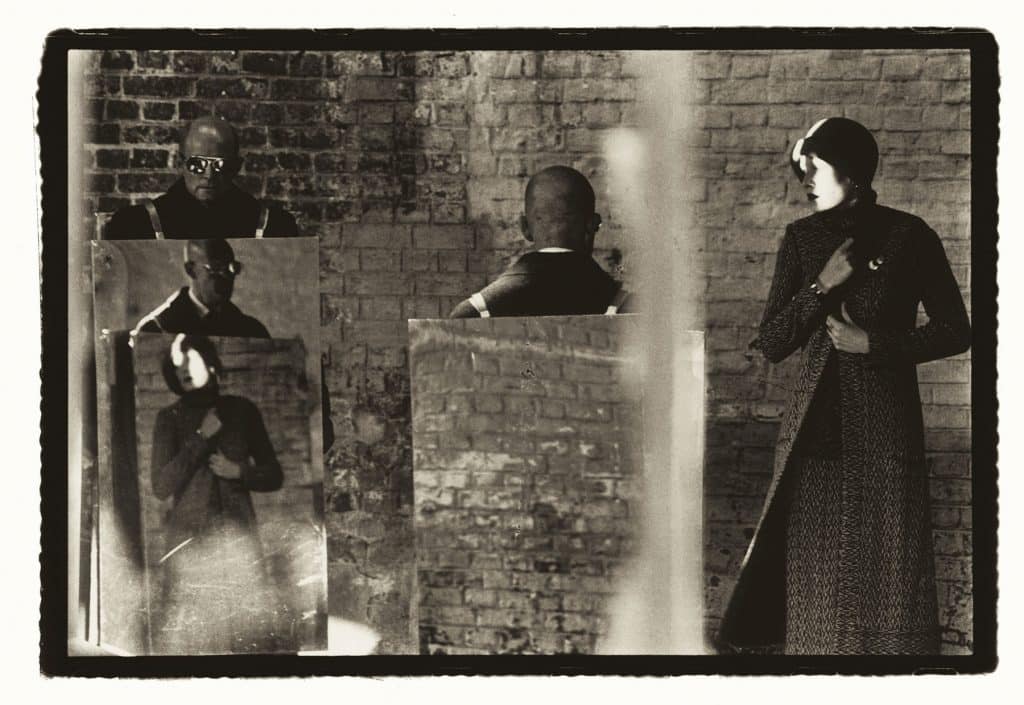

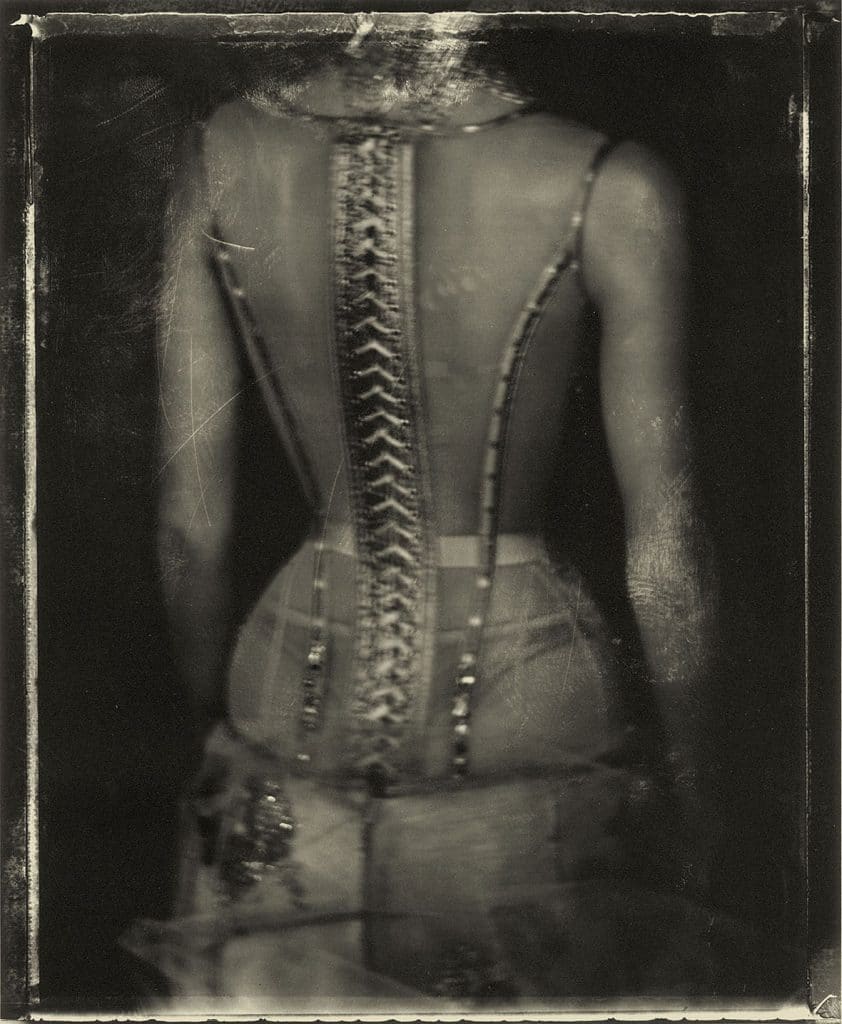

Moon seldom shows the entire figure in her fashion work. The face is often hidden or the head cropped out, accentuating the image’s mystery and ethereality; other times, she photographs her models from the back, as if they belonged to some transitory, transitional place or a fragment of a memory. The face has less importance than “the curve of a neck, the sway of a hip, the flicker of a hand,” Moon explains.

In these compositions, she wanted the women to convey both strength and fragility. She was aiming to create “something that could distance me from the coded language of glamour,” she once told her friend, the painter Ilona Suschitzky. “I was looking for something more intimate. It was the backstage that interested me — the in-between second before the gesture was complete.”

Timeless, sensual and elusive, Moon’s depictions of femininity strongly contrasted with the sharp, glossy, erotic fashion photography of the time, produced in an industry dominated by men. Her first campaigns were quickly followed by ads for Dior, Chanel, Comme des Garçons, Christian Lacroix, Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto, as well as by editorials in Vogue, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, Marie-Claire and Life. She also defied stereotypes in 1972 as the first woman to shoot the Pirelli calendar, which was conceived in the 1960s as sexy, high-gloss promotional material for the Italian tire company but soon became an art object, shot by some of the world’s most prominent fashion photographers.

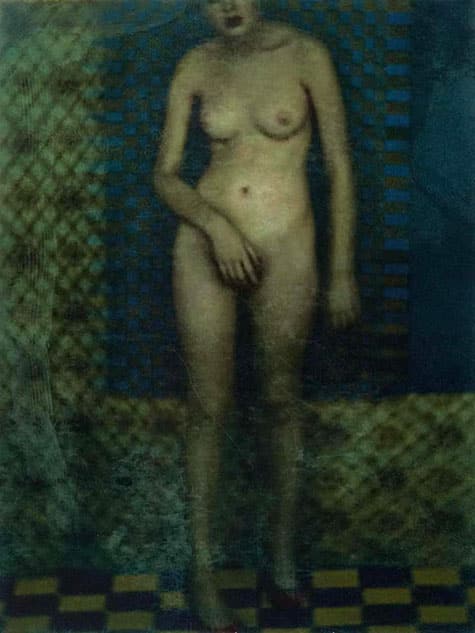

Although Moon continued to pursue this line of work, after the unexpected death of her assistant Mike Yavel, in 1985, she decided to focus on personal projects, producing images with the same grace, poetry and sense of transience as her fashion ones. Depicting still lifes, plants or animals (from peacocks to pachyderms), the mysterious photos were shot in both black and white and color. Blurring, unusual cropping, scratches and distortions give them an almost painterly aspect, especially those taken using Polaroid positive/negative film. The technique dovetails beautifully with Moon’s intuitive process, which embraces imperfections or, as she has put it, accidental traces that give “a fragility to the picture.”

In addition, she works with a rare color-printing technique known as direct-carbon printing, which produces saturated hues that add to the sense of unreality. These are also called Fresson prints, named for the French family that developed the technique, which has been handed down from one generation to the next since 1899 and some of whose elements remain secret. Moon explains that she always includes mysterious shadows, low-speed-exposure effects and double exposures, a process that evokes “the movement of the wind,” as she has put it.

Since the 1980s, Moon has been making haunting, often unsettling short films based on the fairy tales of Charles Perrault and Hans Christian Andersen — including “Bluebeard” (The Red Thread, 2006), “The Little Mermaid” (The Mermaid of Auderville, 2007), “Little Red Riding Hood” (Black Riding Hood, 2010) and “The Steadfast Tin Soldier” (The Screech Owl, 2005) — using her art to transpose the stories into contemporary contexts.

She has, as well, filmed documentaries about her close friend Cartier-Bresson, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Point d’interrogation? (Henri Cartier-Bresson, Question Mark?) (1995), and the legendary photographer and painter Lillian Bassman, There’s something . . . about Lillian (2001), revealing their strong connection by showing the way Bassman’s work transcended fashion photography to become fine art. Moon also directed the feature film Mississippi One (1991), especially beloved in Japan, about a depressive father who kidnaps his young daughter; its title evokes the common system for counting seconds — Mississippi one, Mississippi two, Mississippi three and so on — which is used in darkrooms when developing photos.

Her most recent project, “Time at Work” (2018– ), is a series of small-format images and a short film that embody the concept of transience. Moon created the new photographs from old Polaroid positives she came upon by chance that had never been fixed and had, therefore, changed over time. “Some were unexpected, others just spoiled, many erased little by little,” she explained for a 2018 exhibition of the images, adding that the show told “the story of time passing, of how time erases. The story I tell is not totally mine, but the story of these photographs before they disappear.”

Like all her work, the new series reflects Moon’s fascination with the passing of time. The soft-spoken photographer often quotes this line by T.S. Eliot: “Time past and time future, what might have been and what has been, point to one end, which is always present.” Eliot never saw her work, but he captures it exactly. As Moon herself has said, “I don’t believe I can say it any better.”