Maybe it's the fading light, or the rain streaking the windows that face New York harbor, but Michelle Williams hardly resembles the delicate waif evoked by directors, paparazzi, and my predecessors in profiling. Thirty-six years old, two decades into an ever-expanding career, eight years past a public family tragedy, and probably on the cusp of her fourth Oscar nomination, she still has those apple cheeks and that broad, tight smile. But her face is lean, her hair a jagged bleached bob, her laugh a little brassy. Her gaze is more direct than demure, except when she clamps her eyes shut to craft an answer more careful than the one she'd rather give (or ends up giving anyway).

We were supposed to do something fun out here in Red Hook, an arty, isolated knuckle of Brooklyn where she and her 11-year-old daughter, Matilda, have lived for four years. Instead, we're sheltering in the patio café of a bustling Brooklyn grocery store. Sparrows dart between us, triggering contagious chuckles. "Who let those birds in here?" she asks. "Very hygienic."

When Williams is filming in and around New York, she calls it "working from home," but in this case she really is. She lives directly upstairs, in a two-bedroom apartment carved out of a converted warehouse. That's her Volvo station wagon in the parking lot.

After two magnetic Broadway runs—playing Cabaret's Sally Bowles in 2014 and earning a Tony nomination for Blackbird last year—and work for Louis Vuitton that put her casually luminous style on bold display, Williams has returned to the screen this season in two powerful performances. She plays a faux-hipster Montana mother in Kelly Reichardt's Certain Women, and her devastating turn in Kenneth Lonergan's Manchester by the Sea was tipped for an Oscar a full year ago. Consider them two very different snapshots of an ongoing transformation: from celebrated indie ingenue to muscular, chameleonic movie star in the mold of Cate Blanchett.

"She's clearly interested in acting and not just in being a movie star," Lonergan says. "You can tell the difference pretty easily when you have an actor who embraces a variety of different parts and is not just interested in being pretty. There's just a certain depth." Louis Vuitton creative director Nicolas Ghesquière sees it in everything she does: "She has both the incredible curiosity and open-mindedness that an artist always wishes to keep from childhood," tempered with the "strength that only life, experience, and uncompromising integrity can teach you." Those are the ingredients of her soaring career: two decades' worth of roles chosen on unflagging instinct, which she can't help fleshing out with the hard-won lessons—and sometimes the scars—of a life fully lived.

After six years on Dawson's Creek, which ended in 2003, she fled teen TV for small films and smaller plays, then found unexpected fame—and real-life love—on the set of Ang Lee's hauntingly beautiful Oscar winner Brokeback Mountain in 2005. For a couple of halcyon years, she and Brokeback costar Heath Ledger (both of whom earned Oscar nominations for the film) and Matilda were a celebrity family of a very specific kind. They found pleasure in the open normalcy of Brooklyn's upscale bohemia. Their Boerum Hill town house may have had six bedrooms and a three-car garage, but they still pushed their Maclaren to a diner for breakfast, shopped at Trader Joe's, and took the G train to Williamsburg, having mastered the art of the playdate.

Then it all ended, famously, in a 2007 breakup and, five months later, Ledger's death from a prescription-drug overdose in January 2008, followed by a paparazzi barrage that nearly chased Williams out of Brooklyn for good. "We were trying to deal with grief, and that can't be dealt with publicly," she says. She thought about quitting acting, "but what I wanted to quit was attention." Ultimately, she dug herself out by playing, of all things, a tabloid-hounded celebrity, Marilyn Monroe, in 2011's well-received My Week With Marilyn, for which she was Oscar nominated and which also gave moviegoers their first real glimpse of Eddie Redmayne (as her lovesick paramour). "That lit a match," she says, "and put me on the road that I'm on now—exploring physicality and space rather than a character in this little box." In other words, inhabiting Monroe's alien body—for which she wore padding and strapped her knees together to get the wobble down—allowed her to escape her own head.

Cabaret on Broadway was her first foray into musicals. In the role, she polarized theater critics—their knives already out for Hollywood interlopers—by deliberately reinventing the sexpot Sally Bowles as a subtler creature. "I fell in love with singing and dancing," Williams says, "because you can't not be happy while you're doing it." She's come to our interview from a rehearsal for The Greatest Showman, a Fred-and-Ginger–style movie musical in which she plays Charity, the wife of legendary circus founder P. T. Barnum (Hugh Jackman). "Also, I just got a really good job," she says in a purr, smiling conspiratorially. "I hope I'm not jinxing it." It will be announced a week later. "I'm going to play Janis Joplin! There's singing and dancing!" She smacks the patio table. "I found it! It's like everything has been leading up to this."

Since 2008, she's been romantically linked to Spike Jonze, Jason Segel, and, most recently, the novelist Jonathan Safran Foer, but she diverts a question about the latter. "It's not naturally my inclination to be a boundary draw-er," she says, shutting her eyes and pinching the bridge of her nose. "I'm like, 'Open up all the doors and the windows and let everybody in.' That's the aim of my work, too." But this isn't acting. "It's been a really, really long time since I've been in an interview. But I have better boundaries now. I feel less susceptible to emotional wreck-diving to come up with explanations for everything."

And then, we head to "church." That's what Williams's neighbors call the supermarket underneath her apartment. At the cheese counter, one worker asks after "the little one." "We're very well known in cheese and bagels," says Williams, who buys me a chunk of Midnight Moon—Matilda's favorite. For the first time, I take in her full regalia: shiny cropped leather jacket, rough wool turtleneck, and burgundy boat shoes festooned with tassels. "This is what I've been wearing for the past three years," she says self-deprecatingly when I comment on her signature Brooklyn-glam style.

Williams is late for dinner, and soon those boat shoes will be skidding along slick cobblestones to the Good Fork, a folksy restaurant nearby. But as we're saying good-bye, Matilda appears. Leaning in for a hug, she begins to recap the trials of a fifth-grade day with ebullience and a touch of irony. Like much of the life that led Williams here, introducing Matilda to a reporter was not part of the plan.

"I stopped having a proper education at the age of 15," Williams says. "I think that's why I want so much for Matilda to have a normal life." Today we're at Fort Defiance, a much nicer Red Hook café on a much sunnier day. Williams doesn't always wear the same outfit after all; beneath her denim jacket is a short black dress printed with silver flowers. Shooting Certain Women—a trio of vignettes about women struggling to find their place in macho Montana (Kristen Stewart and Laura Dern also star)—reminded Williams of the last time her own childhood felt normal: "how happy and grounded I was."

Williams was born in Kalispell, Montana. Her father, a self-made commodities trader, ran unsuccessfully for Senate when Michelle was a toddler; her mother was a homemaker. Her parents moved Michelle and younger sister Paige to San Diego when Michelle was eight, and soon after she began carpooling to L.A. for auditions. At 15, she became legally emancipated from her parents—more to get around child labor laws than to escape friction at home, she's said—and lived alone in L.A. She's remarked on being "very, very lonely" there, feeling like "prey." She earned her high school diploma through a correspondence course "from the back of a magazine," she says.

Everyone will tell you that Williams approaches her roles with the focus of a PhD candidate. "I feel like a kid in school all the time," she says, "just studying and trying to do well on that test. I would be a little worried for myself if I weren't an actress—unless I met a really nice guy and had a bunch of kids or something. I really like being a mom." Motherhood became another topic of intense study. "I remember when she was pregnant with Matilda, visiting her and Heath in Australia," says the actress Busy Philipps, one of Williams's best friends. "All the research she was doing about parenting and birthing and tribal cultures, it was like she was taking an advanced course in child-rearing."

The two met on the set of Dawson's Creek, which was shot in the small town of Wilmington, North Carolina—allowing Williams to get out of L.A. When guys at local bars hit on the underage duo, Philipps says she handled the brush-offs. She felt protective of her more private friend, and still does: "I am one of those actors that share probably too much, but I appreciate Michelle's ability to contain herself. People point to 'Oh, well, she's had tragedy.' But she was like that always."

Dawson's Creek shone a spotlight on its young cast for six long, formative—and fame-making—years. "It's a lot of your life that doesn't feel like it's in your control—it sort of owns you," Williams says. "It feels a little bit—tight." Williams downplays her own agency with regard to her career: "I just see what moves me." But Philipps will have none of it. "She's not giving herself enough credit," she says. After Dawson's, "I know the things that she was turning down—big TV shows. She really held out. She didn't want to continue down the same path."

What ultimately moved her was Brokeback Mountain, Ang Lee's epic of forbidden love between two cowboys on the range, which was hardly a recipe for fame and fortune, until it was. Then came Ledger and Matilda, of course—and the tabloid onslaught."If you feel like people are watching you, it's impossible to have an authentic experience of being alive," Williams says. "There's a performative aspect and a guardedness, and that's just death. I don't know how to live like that, and I don't know how to give a life to my child like that." Tired of having to sneak her toddler out of her own home, Williams bought a small house in rural upstate New York after Ledger died. They lived there almost five years. When they returned, it was to Red Hook, where they could be "totally left alone."

Today, Matilda seems to be "in a sweet spot," Williams says. "I would never want to sell any idea of parenting that's not 'It's a long, hard road,' but we seem to be in a kind of magical clearing." For example, "We had a really nice summer. I didn't know how to do summers—how to optimize them. I would see other people making plans and going places, having a great time, and I was just like, 'I'm just trying to get to okay! What's all this fun people are having?!' I think it's the progression from doing okay to doing well."

Williams's second much-deserved Oscar nomination, for the heavily improvised Blue Valentine, was perhaps hardest won. "I couldn't really form sentences," she says. After taking a year off in the wake of Ledger's death, she faced the role, opposite Ryan Gosling, of a mother whose marriage was cracking apart. "I was scared," she says. "Everything that used to feel natural felt totally unnatural." It helped that her character was supposed to be numb. "In some way, her inactivity was the role—her repression, her silence." She likes to paraphrase a Flaubert quote: "Be regular and orderly in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work." That quickly became her new approach: steady for her daughter, increasingly brazen on the set and the stage.

Cabaret was a real risk, and so was her next Broadway show, Blackbird—a physical and emotional roller coaster: Her character, Una, confronts a middle-aged man over an affair they had when she was 12. "It requires gutting yourself for the entertainment of others," says Jeff Daniels, her costar. "Michelle wasn't afraid to do that. So many performers have this need to be liked, to go to the audience seeking their approval. We made it a backstage mantra, as if turning to the audience and saying, 'Keep up.'"

The newfound courage and confidence that Williams earned onstage translates beautifully onto the big screen in Manchester by the Sea. "Everybody talks about the silences in movies and how interesting they are," she says, "but it's a lot easier than connecting beat to beat, line to line, inside of a scene in real time in front of a thousand people. But when I went to make [Manchester], I felt a little bit more freedom, more access inside of myself."

Manchester follows Lee, a Boston janitor played by Casey Affleck, whose brother's death forces his return to the titular Massachusetts town, where he's something of a pariah. We learn why through the eyes of his ex-wife, Randi, in a pair of scenes that turn a slow, evocative film into a gut-punching tragedy. Lonergan first encountered Williams at a reading of one of his plays. When he offered her the part of Randi, "I got a little bit weepy," Williams says; working with him was "one of those dreams you keep under your hat for decades."

Randi appears in flashbacks as the alternately indulgent and exasperated young wife of the hard-drinking Lee. When they meet years later, she gives a showstopper of a speech: It's a requiem for a love beyond logic, a life preserver thrown out to the only person on the planet who shares her agony. And it's all spoken (in a working-class regional accent) without a glimmer of self-consciousness. "It's absolutely crucial to the plot," Lonergan says. "It's a microcosm of the whole movie: people in a lot of pain trying very, very hard to do right by each other."

Williams wasn't on set every day, as Affleck was, so she had to turn into Randi on a dime. "I'd gotten accustomed to showing up at work and feeling horrible," Affleck says. "Michelle had to do the impossible task of coming into each scene cold. She was trying to be a complete person. There's no performance element. It felt like she disappeared."

The work of disappearing started long before the shoot. At the café, Williams shows me a picture on her phone: a woman's loose black leather boots, photographed surreptitiously in a Manchester Rite Aid. "I stalked people," she says. She waited at schools around pickup time. When she heard from a bar patron about a mother of four with the perfect accent, she invited herself over to her house. "Part of me felt voyeuristic, but the other part felt in the service of something else."

Certain Women is Williams's third movie with indie director Reichardt. She first worked with her on 2008's Wendy and Lucy, playing Wendy, a young drifter with a dog. That character is a long way from Certain Women's Gina: a steely ad exec hell-bent on acquiring "authentic" historic sandstone for her family's mountain cabin. She's the film's least appealing character; her husband and daughter don't even like her. Williams worried to her costars that viewers would hate Gina, "but they were like, 'We're all Gina. We're all spread a little too thin, working too hard, underappreciated, trying to find something authentic, but meanwhile our lives are completely inauthentic.' I hope that registers."

Walking her home, it occurs to me that Red Hook abounds in exactly the kind of rugged faux-authenticity Gina craves: perfectly oiled beards and prefaded Rag & Bone shirts; artists with unaccountable incomes; purveyors of artisanal whiskey and Key lime pies. An obvious question comes to mind: Having found her privacy in a pocket of roughed-up privilege, does Williams—an actor so skilled at disappearing—ever wonder about her own authenticity? "No, I really don't," she says. "I'm trying to move toward something authentic at the core. It reminds me of when I was on Dawson's Creek. I didn't have a lot of respect from the professional community. I wanted self-respect, and I wanted it from a community that I could call home. Making these very personal choices was a move to be myself, and to have that self seen."

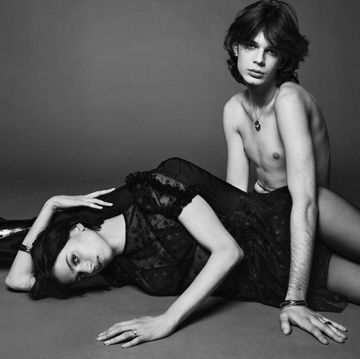

Styled by Samira Nasr. Hair by Kevin Ryan for Unite; makeup by Angela Levin at Tracey Mattingly for Chanel Makeup; manicure by Gina Edwards at Kate Ryan Inc. for Chanel Beauty; prop styling by Dorothee Baussan at Mary Howard Studio; fashion assistant: Yashua Simmons