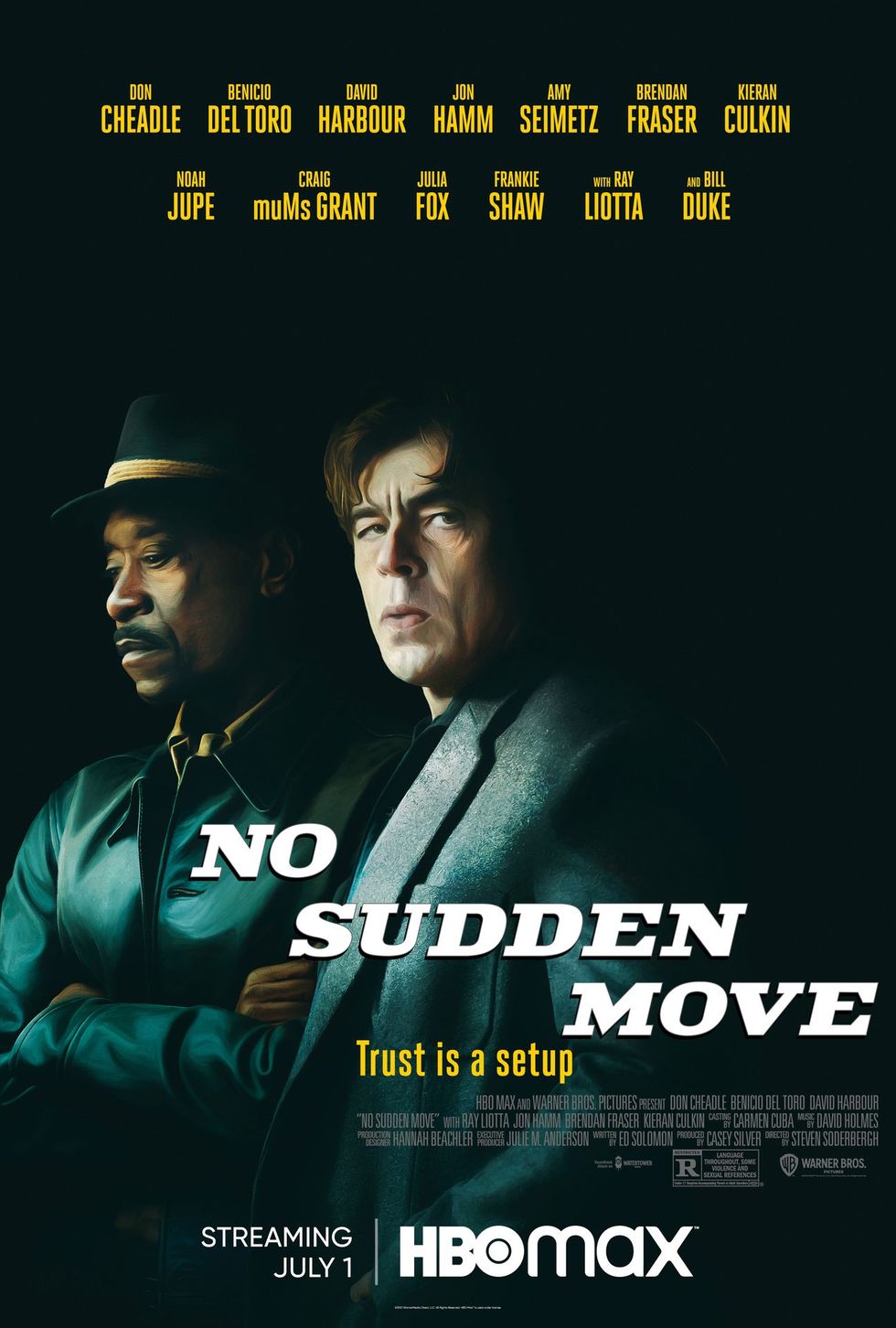

No one makes star-studded crime films like Steven Soderbergh, as once again evidenced by No Sudden Move, a witty, suspenseful and sneakily caustic film about two crooks in 1954 Detroit—Don Cheadle’s Curt and Benicio Del Toro’s Ronald—who are hired, alongside a third accomplice (Kieran Culkin), to babysit a family at gunpoint while the father (David Harbour) retrieves a document coveted by their unknown employer. That’s the set-up for a serpentine saga about greed, ambition and competitive capitalistic enterprise, the last concern coming to the fore once the movie finally reveals the motive behind this underworld plan. Come for the taut tension, stay for the stinging critique of the auto industry’s Big Four and, by extension, a corporate America that comes out on top even when it loses, and against which the little man has little chance. Playing like a grimmer companion piece to Out of Sight (Soderbergh’s prior Detroit-set gem), it’s the sort of adult thriller that gets better as it gains momentum, aided by arguably the year’s best cast, which includes Jon Hamm, Ray Liotta, Amy Seimetz, Brendan Fraser, Bill Duke, Julia Fox, and Matt Damon.

Following Out of Sight, the Ocean’s Eleven trilogy, and Logan Lucky, No Sudden Move reconfirms Soderbergh’s preternatural skill at staging electric capers in which ragtag individuals band together to pull off heists while protecting their necks from dangerous enemies—some of whom are often their supposed comrades. The tonal opposite of Soderbergh’s prior, stellar Let Them All Talk, it’s a stylish and poised triumph, delivering both the sizzling genre goods and shrewd commentary about the larger dynamics that govern this country, from the boardrooms where titans make deals that always pay off, to the backrooms where hoods scheme and backstab in an effort to get ahead. Premiering in theaters and on HBO Max on July 1 (following its premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival), No Sudden Move proves that few directors have Soderbergh’s range, dexterity, and gift for infusing crime films with humor and heft. Ahead of his latest’s debut, we sat down with the filmmaker for a wide-ranging chat about working with familiar faces, producing the Oscars, the ongoing Warner Bros-HBO Max release paradigm, his fondness for stories about thieves, and making studio movies whose prime targets are corporations themselves.

You’ve made a wide variety of movies, but I’d say No Sudden Move is right in the Steven Soderbergh wheelhouse. Would you agree – or is a “wheelhouse” exactly what you want to avoid?

Certainly No Sudden Move is the kind of movie I like to watch, and this seemed like a really good opportunity to use a genre piece as a delivery system for a series of ideas we wanted to have percolating underneath the main narrative. That, combined with the fact that I’ve been trying to find a project to do with Don for quite a while. This really originated from that desire. I had a very basic idea that I pitched to [screenwriter] Ed Solomon about a group of people who don’t know each other and are brought together to do a job, which is a fairly standard set-up. Then we talked about, using that skeleton, how do we pack this with interesting layers? It all came together very quickly. Ed wrote the script fairly quickly, and Warner Bros. said yes immediately. We were one of many productions that got postponed last year; we were supposed to start April 1, and we had to send everybody home. So I was very happy when, about a year ago, Warner called up again and said, do you think you can remount this safely? I said yeah, I think we can. They were very patient.

No Sudden Move is premiering in theaters and on HBO Max, and it’s part of your ongoing production deal with the studio. How has that worked out so far, and are you confident the film can live in both realms (i.e. at home and at the multiplex) simultaneously?

This movie seems to me a poster child for the positive aspects of streaming platforms. This is a mid-range-budgeted film made for grown-ups. This is not something that typically goes out and makes $100 million anymore. For someone like me, who likes making these kinds of films, a platform that wants to make good movies is a great home for me. So personally, it’s been great. I’m halfway through my three-year arrangement with Warner, and it’s working exactly the way it’s supposed to work. We just wrapped another film that we shot for them, and again, it fits into that same category of mid-range-budgeted movie for grown-ups. I just have to go where people see some value in what I like to do, and the way I like to do it.

For me, it’s been a great development, and I’m sure there are other filmmakers who would tell you the same thing – that over the past 5-7 years, there have been a lot of really good movies that have been made only because the streaming platforms want to be in the movie business. It turns out, if you talk to any of these platforms, movies continue to be a huge magnet for viewers. They’ll give you what they call “First Play” data, which is that as soon as somebody gets the app for the first time, they obviously know what the first thing is that they watch. And it tends to be a movie.

Does the HBO Max component put less pressure on the film’s theatrical performance?

In our case, domestically, the release is merely to qualify us in the event that somebody decides it’s Don Cheadle’s year. None of us are really looking at that as a metric for judging how the film is doing. It’s my feeling – I guess we’ll know in a couple of weeks – that this will all work as intended. I think the larger question that everyone has to grapple with, going forward, is that as we come out of COVID and people go back to the theaters, what’s going to work and what’s not going to work? Have their tastes been changed by the last year and a half of being at home? Or will they essentially maintain the kind of interest that they had before we went into the COVID phase, which is this dichotomy of fantasy spectacle on one side, and fairly intense art-house fare on the other side – awards magnets, that kind of stuff?

I think it’s been a frustration for a lot of people that the middle of the movie business has dropped out and decamped for the online platforms. I’m curious to see if we’re going to have more of the same, or if there’s going to be some secular change for moviegoing audiences when they return.

Did those notions factor into the creative process of making No Sudden Move? Or in that regard was it business as usual?

It’s just a movie, so I’m working back from what I want to see. For me, there’s never any sense of, oh, I should be doing something visually different because it’s probably not going to be seen on as big a screen as it might normally. I’m assuming that it’ll work on a big screen and that it’ll work on your iPad. I’m just doing it the way I would normally. I don’t know if other people view it that way, but to me, it’s the same.

You produced the Oscars this year, which were criticized for the way the final Best Actor prize was handled. Were you surprised by the backlash, and were you happy about how it all turned out in the end?

I was happy with everything that was within our control. But look [laughs], trashing the Oscars is kind of like playing basketball with a four-foot rim – it’s really easy. I’ve done it. And when you agree to be a part of that, you know that’s what’s going to happen. We tried to stay focused on creating something that felt distinctive and felt like there was intention behind all the choices. In that regard, we were really pleased, and we all had so much support – from the Academy, from the network. It was intense, and I wish I hadn’t been directing a movie while that was going on, because it’s very labor-intensive. But I came away very pleased with the things that were within our control.

I’ll also say, it was almost worth doing it, just to have the feeling of not having to do it the following week [laughs]. That felt so good, it was kind of worth the other stuff. Being free of it was incredibly liberating.

No Sudden Move is a really masculine film, which makes it the tonal opposite of Let Them All Talk. Was that a purposeful shift on your part?

It’s good luck for me that that turned out to be the sequencing. It’s more fun if you’re moving from one project to another when there’s contrast between the experience you just had, the problems you had to solve, and the one in front of you. I was very excited about the fact that this was, in my mind as it must have been in yours, 180 degrees from what I’d just made. Also, coming out of COVID, I had a lot of pent-up visual energy to burn, so this felt like a movie where it was appropriate to really push the visual side of the movie into a fairly theatrical and dramatic space. I was thinking about all of these ‘50s melodramas and crime films that had a really lush, contrast-y feel to them. I really wanted to recreate that, because I felt it was appropriate to this.

For me, and I think for everybody, I was so excited to be back on a film set, because when we got the call on March 16 to get on a plane and go home, nobody knew what that meant. And especially, the fact that we went back to Detroit. When we got back, all of the people that we’d been working with locally said that they were really scared that not only was the movie going to get shut down, but that somehow, somebody would decide, why are we going back to Detroit? Why can’t we shoot it somewhere else, that’s less expensive and that’s not as much of a hassle? It was important to us to go back, and to be able to shoot this movie in Detroit.

There was a huge financial downside to doing that, because they have no incentive program in Michigan, so things just cost what they cost. We went there because we felt it was important, given what the storyline was, for us to be there. And for me, I’m not sentimental by nature, but I’d had a really great experience in Detroit on Out of Sight. So karmically, I thought it was worth it. I had another great experience, and it’s another movie that I feel really happy with, and it’s an interesting companion piece to Out of Sight in a lot of ways – they’re different in some ways that are important, but they’re related.

In the two decades since Out of Sight, what’s changed about the city?

The face of the city has changed drastically. And in fact, it had gone through several different changes, and is continuing now to go through more changes. It’s such a fascinating city. It’s so emblematic of a certain kind of American city – one that can only exist in America. This time, especially during our hiatus, I spent a little time reading about the city, and one thing I noticed going back, just on a physical level – it’s so huge! The footprint is gigantic. It’s a big, sprawling city. I think you often have that tendency to think of a city only in terms of its downtown, but Detroit is massive.

You have these neighborhoods that have these completely distinct feels to them, and it was kind of wild. For instance, the Wertz house and neighborhood is part of a pretty sizable area in which the houses look remarkably similar to how they looked 60 years ago. We really didn’t have to do a lot on those blocks except to bring some cars in. People like that style of home, and they’ve maintained it, and there was block after block after block of that look and feel. So for us, it was great. And to be able to go back and shoot in the lobby of what used to be General Motors, and to be in that actual building – just the scale of it, and the craftsmanship, of these old, huge structures. For a filmmaker, it’s fantastic.

There’s an obvious narrative reason to set the film in 1954, but were there additional benefits to setting it in the past – for example, not having to account for complication-ruining technology like cell phones and GPS?

If you talk to Ed, who has a better memory than I do, he would say that we were working back from the MacGuffin. We needed a good narrative hook to build something on. If we have the premise of three guys who don’t know each other who are coming together to do this job, and there are real trust issues, what is the job? What is the MacGuffin that they have to get, or to execute? We would have conversations about corporate espionage, which I think is a really interesting subject, and some of my favorite films have used that as an entry point. My recollection is that Ed came back and said there’s this real thing that happened with the catalytic converter where the Big Four had this technology, suppressed it because it was a pain in the ass, and it took the Justice Department, fifteen years later, tapping them on the shoulder going, “What are you guys doing? This is collusion. You can’t do this.” I didn’t know that story, and I thought it was fascinating.

Once he had that on the table, things started to fall into place pretty quickly. Because as you said, back then, the lack of technology is just more cinematic. It was a real pleasure to not have to shoot screens. I went from No Sudden Move to KIMI, the movie we just wrapped, which is tons of screens – you’re talking about a data analyst, this is her day job, and all she does is sit in front of a screen. It was a nightmare.

I kept thinking, while watching No Sudden Move, that it would ruin everything if they could text each other during the crime.

No, it’s the worst. There are no obstacles anymore to finding something out. It can be a real problem. The best things that we’re seeing in the contemporary crime field are when people have come up with creative ways to mitigate this really uncinematic thing that is ubiquitous, and we’re surrounded by, which is smartphones. When people are able to move around that and come up with story points in which that is no longer an issue, it makes everything more fun.

You have a recurring fondness for crime films. Is it their clockwork mechanics, or the teamwork aspect – or something else entirely – that appeals to?

It’s so odd, because there’s nothing in my background that would suggest a connection to, or an affinity with, crime films – other than the fact that I love movies, I grew up loving movies, and crime films are great movie material for a couple of reasons. One is, all drama is about conflict, and when you have a crime film, the conflict is stark, and the stakes are high, because there’s the threat of physical violence and incarceration everywhere. Plus, betrayal, which is another cornerstone of conflict and drama, is really central to any crime story. There’s always this issue of who you can trust, and what people are willing to do, or what compromises they’re willing to make, to pull off that score, or to not go to jail.

Then the other component which I probably was responding to was, it’s a genre that really benefits from bringing a certain cinematic style to the table. It begs for that. For a filmmaker, it’s very enticing. There are just a lot more justifiable and organic visual choices you can make in a crime film as opposed to a family drama, or something like Let Them All Talk – which is not boring to look at, but I have to make sure that nothing I’m doing directorially is getting in the way of these performances. Whereas in a movie like No Sudden Move, you have license to raise your hand a little bit, because the audience feels like that is absolutely appropriate to this kind of film.

Were there crime films you were thinking about when designing No Sudden Move’s style?

I was thinking mostly about these two Nicholas Ray films, Rebel Without a Cause and Bigger Than Life, which are CinemaScope, really using the frame, really high contrast, strong colors, just beautiful and bold. I think if you overlaid them, you would see some very, very obvious similarities. But at the same time, I wanted to put myself in a space of recreating my memory of what those movies look like, as opposed to specifically trying to copy things. Because I find that, if you’re working off your impression or feeling of something, as opposed to having it right at hand, you get a more interesting, idiosyncratic result.

The best example I can give of this is the love scene in Out of Sight between Jennifer [Lopez] and George [Clooney]. In my mind, I was recreating exactly a sequence from Don’t Look Now that Nicolas Roeg had made, where he’s crosscutting between Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland making love and getting ready to go out in the evening. That was what I had in mind as we were shooting and cutting that sequence. A year later, I watched Don’t Look Now again, and I was like, that’s not anything like what I remember. Like, not even close! And thank god. I was working off some kind of degraded, refilled idea of it, and fortunately because I was, I pushed that sequence into a direction that I might not have if I’d had Don’t Look Now on set with me.

How did this reunion with Don and Benicio come about?

In the case of Don, it’s in line with the fact that there are a lot of people who I’ve worked with multiple times. Especially when you feel synchronized with somebody, not only creatively but in your worldview, then there’s another layer of connection. Don and I were friendly and had remained in regular communication, even after the last time we’d worked together, so he was someone in the back of my mind who I thought, we’ve got to do something else. This can’t be it.

Ed and I, coming out the other end of Mosaic, and wanting to work together again because we had a good experience – this was one of those situations in which a lot of repeat business was stacking up. I always pay attention to that, or at least, I let that flow when it starts to happen. And Benicio seemed like such a great contrast to Don, because in the structure of it, you could argue that the film is a bit of a two-hander – this relationship between the two of them is the core of the movie. Knowing them both, I liked the idea of them in a room together. Luckily, as I predicated, there’s a reason Don and Benicio are regarded as well as they are – it’s because they bring a lot to the table. I give my cast a lot of freedom and a lot of responsibility, and I really like sentences that start with the words “What if?” And both Don and Benicio bring a lot of those questions.

In particular, they’re thinking about the whole film. They’re not just coming to me with stuff about their character; they come in and talk about the piece as a whole. In fact, Benicio had a question about David Harbour’s character. He was just asking a question, but it was a question that triggered in my mind an avenue that could be explored. I went to Ed and said, Benicio is curious as to why Matt Wertz behaves the way he behaves when the invasion starts. Benicio is like, right at the beginning, he’s acting like he has some sort of pre-knowledge. I said to Ed, I think he’s right, so why don’t we lean into that and create a scene at the motel where we explicitly explain that this whole thing started a week ago, and it was started by the two of them!

That turned into one of our favorite scenes in the movie. It’s heartbreaking, it’s funny, and with him trying to slow her down so he can explain, it’s just painful, but fantastic [laughs]. That’s a situation where we’re in the middle of shooting when he asks me that question, and I go to Ed, Ed writes the scene, and then we jam it into the schedule; it’s the last thing we shot. That’s what people like Don and Benicio bring. It’s the rigor, and they want to make sure that we’ve chased down all the variations, and that we choose the version of the idea that’s the strongest, and the one that tracks.

A lot of times, you’re just going through it line by line, and you’re going, is this tracking? Because in a movie like this, it’s all about how information is released, and when. You want people chasing you, but you don’t want them frustrated. You need to make sure you’re dropping information in a way that’s imprinting. You may think, oh, but we mentioned it, he says so-and-so’s name, only to find out that just went right past people. You thought it landed, and it didn’t. So I think that’s the biggest challenge – the time-release of information.

The film eventually takes on an added dimension via its critique of the Big Four, and corporate America. How do you infuse the material with that larger import without letting it overwhelm the crime plot? And is it fun to get that sort of censure into a film produced by an entertainment conglomerate?

Yeah, absolutely. The good news was, once Ed found that story, all of the stuff starts to accrue immediately. There are tributaries to everywhere, and now it becomes a discussion about how many of them to explore, and to what extent, so that like you said, it’s supporting the plot without dominating it. You don’t want all this stuff around the periphery to pull people’s focus from the A-line narrative. But if you can create all this percolating supporting story, it makes the movie feel bigger, in my mind.

The other thing – and this is how crassly stories get built sometimes – one of the other things I said to Ed was, I want it to culminate with our version of the Ned Beatty scene in Network, where a character that we haven’t met just hijacks the movie for ten minutes with this giant monologue. I want it to lead to that. Ed’s like, okay, and he starts reverse-engineering the plot so we have our Ned Beatty scene from Network. There’s another scene that’s probably more similar, and that’s Absence of Malice, which concludes with this very long, fantastically entertaining scene in a conference room. It’s a spectacular scene; I just find it incredibly pleasurable. Ed and I talked about that too. It’s got to have that feeling too – it keeps morphing, and moving into new territory as it goes on. Every three minutes, there’s a new avenue which it’s pursing. Ed did a really remarkable job of synthesizing all this stuff that I was throwing at him that I wanted in the movie.

Have you ever felt pressure – or been propositioned – to do another Ocean’s film?

I don’t feel that. I’m just going based on what I’m excited by. Certainly Logan Lucky is very much a cousin to an Ocean’s film, more than No Sudden Move. My way of scratching that itch is finding that new universe in which to play. But look, as time goes on, and I make more films, the challenge of finding a fresh take increases, for sure. I don’t want to do exactly what I’ve done before. Going forward, if I’m going to make another crime piece, there has to be some aspect to it that’s completely new to me, and that represents a challenge.

The worst thing in the world is to feel like I got this. I have to go to work scared. There has to be something about the thing. It could be that we have eight days on a boat to do it, and we’re storm-chasing [like Let Them All Talk]. Or it could just be a creative aspect that I feel is complex, and if it’s two degrees off, then it might as well be 180 degrees off, so we’re trying to thread a very, very small needle. But there has to be something that scares me, because otherwise, you might as well be directing from the back of the limousine. Like, what are you doing?

There’s been talk about reviving The Knick, with Barry Jenkins possibly directing. Is there any chance that might happen?

I hope so. I read a fantastic pilot and bible for the future version, and I can only hope that they’re going to say yes and move forward with that. I made it clear to everybody, I’ll just be consigliere. I don’t want to be actively involved; I want you all to do what you want to do, and I’m here in case I’m needed. It’s really their project. I can only say that I loved what I read. I felt they did a beautiful job of continuing with the ideas that were set up in the first two seasons. So I hope it moves forward, and I hope it moves forward soon.

Any movement on the sex, lies and videotape sequel, which would reunite Andie MacDowell and Laura San Giacomo? And how does that fit into your feelings about not duplicating yourself?

I found a way in. There’s an important subject, in terms of an aspect of how we live our lives, that the two sisters…there’s a part of life that they could not have confronted yet because they were not parents. There are some things I want to get into about being a parent that following these two characters, thirty years later, allows me to explore in what I feel is an interesting way that seems intuitively correct. Because yeah, why go back unless you’ve really got something?

It was something I’d been wanting to do for a while – these questions about parents and children, and especially daughters and mothers – and I was sitting around during lockdown, looking for something to occupy myself, and thinking the only thing I can do now is write, since I can’t go out. I don’t like writing; it’s why I stopped writing. I like working with writers – it’s a lot more fun. But I had no choice – there was nothing else to do. So knowing that if someone was going to force me to write something, this is a subject that I really want to explore, I just mashed it up with the idea of following these two sisters thirty years later, and them grappling with characters that are the exact same age that they were when we made sex, lies.

I assume revisiting a career-making film like sex, lies is daunting?

It’s about intention. I know my intention is clear, and that there’s no other reason to do this other than me feeling there’s something to really explore and build on. At the end of the day, if that’s a tightrope walk, the rope is five inches off the ground. Like, nobody is going to get hurt [laughs]. So I don’t really worry about that.