Taming Titans

Giant Anthurium Species at Home and Abroad

by Jay Vannini

Anthurium sp. nov. “Cordillera Central”, growing as a hemiephyte in high elevation cloud forest, Risaralda Department, Colombia. Longest leaf blades shown ca. 4.5’/140 cm. This large, showy species is often confused with A. marmoratum and less frequently with A. warocqueanum. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Tropical aroids originating from rain- and cloud forests have had a dedicated following ever since their introduction to northern gardeners in the early 19th century. Among the species that found ready acceptance by wealthy tropical plant collectors in Europe beginning circa 1850 were the remarkable South American Anthurium species that sported large leaves with bold patterns and textures (Veitch, 1906).

Anthurium veitchii at the Palmengarten in Frankfurt, Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. Image out of copyright.

These trophies were considered among the premier floral Exotica of the 1800s.

During peak 21st century Rare Houseplant Mania (2018-2022), large Anthurium species with attractive foliage once again came into vogue and–despite the unsuitability of most of them as subjects for long-term captivity in modern interiors–considerable numbers of them were sold in the US, EU, and Asia from both wild and cultivated sources.

Unlike many easy to grow, sturdy tropical aroid genera that have proven themselves as mainstream live décor items, such as Philodendron, Monstera, Epipremnum, Dieffenbachia, and Aglaonema, most of the oversized Anthuriums have quite specific requirements that are often challenging to meet in our living spaces. Their imposing size even as young plants preclude anything more than the briefest of stays in most grow tents or custom built plant cases, so they are best suited to cultivation in conservatories, greenhouses, and sheltered tropical gardens.

The exceptions to this general rule are discussed in the individual species treatments below.

How big are they?

Debate continues among hobbyists and aroid specialists as to what Anthurium species attain the largest leaf sizes. Claims made by the tiresome armchair experts who populate social media sites regularly tout massive dimensions for plant species whose leaf blades rarely exceed 3.2’/100 cm in either nature or cultivation (i.e., most members of this genus).

For what it’s worth, the greatest leaf lengths I have heard bandied about by people who should know better for some giant species now in cultivation include: 10’/310 cm for the west Panamanian Anthurium pseudospectabile, >8’/245 cm for A. salviniae, >8’/245 cm for one or more undescribed species incorrectly labeled A. metallicum or A. marmoratum in the live plant trade, >6’/185 cm for A. veitchii, 6’/185 cm for A. regale, and >5’/155 cm for A. warocqueanum. I have also heard claims of a few other real whoppers that somehow “got away” sans photographic evidence or as herbarium specimens.

Based on my own experience both in the field and with long-term cultivated plants, together with examination of published data and notes on herbaria sheets, it seems quite clear that most of these claims are exaggerated by greater or lesser degrees. In practice, this translates into use of a “fisherman’s tape measure” that overshoots by a factor of ~15-25% above maximum documented sizes. Any showy aroid leaf blade much over 3’/92 cm in length and similar width is certainly a handful when collected and it is remarkably easy to overestimate actual dimensions even by experienced observers. Trick perspectives–especially foreshortened ones popular with commercial plant photographers of late–together with use of petite human models alongside the plants can produce the illusion in images that the leaves are much larger than they really are.

Likewise, in species with elongated pendent leaves, petioles of up to 24”/60cm in length can also create an impression of far greater leaf size than the ruler evidences. This is especially notable in the southern Central American Anthurium pseudospectabile, A. spectabile, and A. protensum in section Pachyneurium, together with A. wendlingeri in section Porphyrochitonium.

A trio of leaf blades removed from cultivated specimens in my collection in California. Upper, Anthurium pseudospectabile; middle, A. wendlingeri; and lower, A. prolatum. The lower two leaves are within 25% of maximum mature sizes - exceptional A. pseudospectabile can double these dimensions in nature. Measurements shown in feet/inches. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

The largest Anthurium leaf blades that I have measured in nature across tropical America by using my height (6’/186 cm) as a handy metric are : >7’/215 cm for Anthurium pendulifolium in lowland tropical rainforest at the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve in Loreto Department, Perú; ca. 7’/215 cm for A. pseudospectabile in cloud forest at the Fortuna Forest Reserve in Chiriquí Province, Panamá; ca. 7’/215 cm for A. salviniae (as a re-established windfall) in cloud forest on the south slope of Volcán Tajumulco in San Marcos Department, Guatemala, and ca. 5.5’/170 cm for a still undescribed Anthurium section Cardiolonchium in high elevation cloud forest located on the western slope of the Cordillera Central, Colombia.

Anthurium queremalense (ined.) growing as a clambering terrestrial in nature in Valle del Cauca Department, Colombia. Longest leaf shown ca. 4’/120 cm. Image: ©Fred Muller 2024.

Any plant other than a palm with honest-to-God four to six foot undivided leaves is a big critter in most jurisdictions and invariably prompts comment from even casually interested observers. Witness the initial amazed reactions by northern plant aficionados to their first views of jumbo-sized Neotropical Gunnera spp. (Gunneraceae) in nature or gardens. My own encounters with record book size Anthuriums in the wild over the past 25+ years has left me deeply impressed and with a lasting desire to grow something to these dimensions in my own collections.

Under ideal conditions it is likely that many of the largest Anthurium species continue to grow incrementally throughout their lives, but even taking this into account I still strongly suspect that something between 8’ and 9’/245-275 cm is the upward limit for leaf blade length for any naturally occurring plants in the genus. My conviction bet would be that some exceptional A. pendulifolium from sheltered sites in remote parts of the Upper Amazon have the longest leaves of any Anthurium species, likely followed by one of the Mesoamerican birds-nest types also placed in section Pachyneurium, together with still obscure and localized undescribed taxa in section Belolonchium from Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador, including one that has leaves known to reach at least 6.5’/200 cm in exceptional cases. I am also confident that one of the currently unnamed species of huge, contrast vein-type species (i.e. esqueletos) from the cool, rainy uplands of western Colombia will prove the largest of the velvet-leaf forms in section Cardiolonchium and, with exceptionally large leaf blades certainly measuring between 6’ and 7’/185-215 cm, at least a couple are worthy contenders for top billing overall.

To be fair, anyone with clear photographic evidence of Anthurium specimens with leaves longer than any of the sizes listed above are welcome to send it to me at the website email address and I will gladly correct the record and cite the source.

Among artificial hybrids, Anthurium ‘Bigbill’ (A. pendulifolium x A. plowmanii [sic? fide IAS aroid cultivar registry]) is widely acknowledged to be the largest form in cultivation, with leaves reportedly to 10’/310 cm in overall length. Photograph evidence posted online supports this claim. Better known by most growers as A. ‘Big Bill’, the very strong influence, including its great leaf size, of the seed parent is evident in this remarkable cross. Early anecdotal reports cite A. cubense as the pollen parent of this giant primary hybrid.

This article will deal with approximately two dozen Anthurium species from seven currently accepted sections. All are of interest to ornamental horticulture and are known to have maximum leaf blade sizes that approach or exceed 4’/120 cm in length. Herein this measurement refers to total leaf blade length from the upper margins of basal lobes to leaf tip exclusive of petioles. Most species dealt with will be at least somewhat familiar to aroid and other tropical plant collectors while others are obscure rarities, recently described, or novelties pending published descriptions.

For reasons of space, I have opted to omit detailed descriptions of a few large section Pachyneurium and many species of section Belolonchium from Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Perú known to have >4’/120 cm leaf blades, largely due to their overall similarity to close relatives that I do profile below. Notes on, and images of, many of these jumbo-sized plants will be provided from observations made in nature throughout Mesoamerica, Panamá, and the northwest Andean countries as well as in my personal live plant collections in Guatemala and northern California.

Mature Anthurium sp. cf. bogotense Schott in high elevation cloud forest, Cundinamarca Department, Colombia. Like many other terrestrial north Andean Anthurium species placed in section Belolonchium, the leaf blades on these plants commonly exceed 42”/110 cm in nature. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

The first order of business here is to sweep a few sticky cobwebs away.

One formerly obscure but now ubiquitous Anthurium name that first surfaced in the mid-19th century and that has been consistently abused by vendors since the 2010s by being (mis) applied to all manner of large leaf esqueletos they offer for sale. These include those propagated from seed off a famous cultivated giant specimen grown in Chiriquí Province, Panamá (though the Finca Dracula plant is almost certainly of Colombian origin) as well as wild-collected western Colombian and north Ecuadorean taxa. I am, of course, speaking of:

Anthurium metallicum Linden ex Schott

Originally described from horticulture in Heinrich Wilhelm Schott’s Icones Aroideae et Reliquiae (1860), and illustrated in drawings #643-645, this image caught the eye of botanist Jorge Jácome about 20 years ago. The similarity of this plant from an unknown country of origin to collections he had made in 2000 near the Tequendama Falls on the Bogotá Plateau in Cundinamarca Department, Colombia (Jácome #3147-3148) led him to critically compare the two. Reasonably concluding that he had rediscovered a remarkable, long-lost taxon, he wrote a detailed description of the new material, together with that of Anthurium gustavii Regel, for a short article and published his findings in a paper coauthored with Thomas Croat in Aroideana (Jácome & Croat, 2005).

Unfortunately, Jácome either ignored or failed to notice that Schott’s color illustration and accompanying description shows/states that Anthurium metallicum has green spathes (fide T. Croat). Jácome’s original collections (as well as subsequent wild accessions from the region that I have seen) have red spathes.

This mistake was compounded by his confused description of the inflorescence: “…spathe dark pink to red, 15-21 cm long, 2-7.5 cm wide, elliptic, coriaceous, recurved at anthesis; spadix stipitate (stipe 1.5 cm long, 9 mm diam.) darker green than the spathe, yellowish green, 12.5-19 cm long to 1.4 cm diam…” (emphasis mine).

The inconsistency in the description of spathe color between Jácome’s collections and those shown in the Schott illustration may have been attributed by him to major color change that occurred between early and late stage inflorescence development, and so of minor import. Or it may just be a case of a lapse in editorial oversight…these things do happen.

Large-growing, contrast-vein Anthuriums from Andean Forest relicts of the Bogotá Plateau and the western slope of the Cordillera Oriental have been artificially propagated in Colombia and are now grown in private collections there as well as being on display in the Bogotá Botanical Garden’s main greenhouse. I have examined several of them in Bogotá at large mature sizes, and it is clear the spathes are dark pink or red well prior to unfolding and remain red through until senescence.

Anthurium sp. “Cordillera Oriental” in the Jardín Botánico José Celestino Mutis in Bogotá, native and very likely endemic to the area. These large plants on display in the Tropicario are labeled A. metallicum, based on the description provided in Jácome & Croat. Note the vivid red spathe color evident even in the developing inflorescence, a feature shared with other regional Anthuriums that has led some to conclude that it is just a local form of A. sanguineum. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

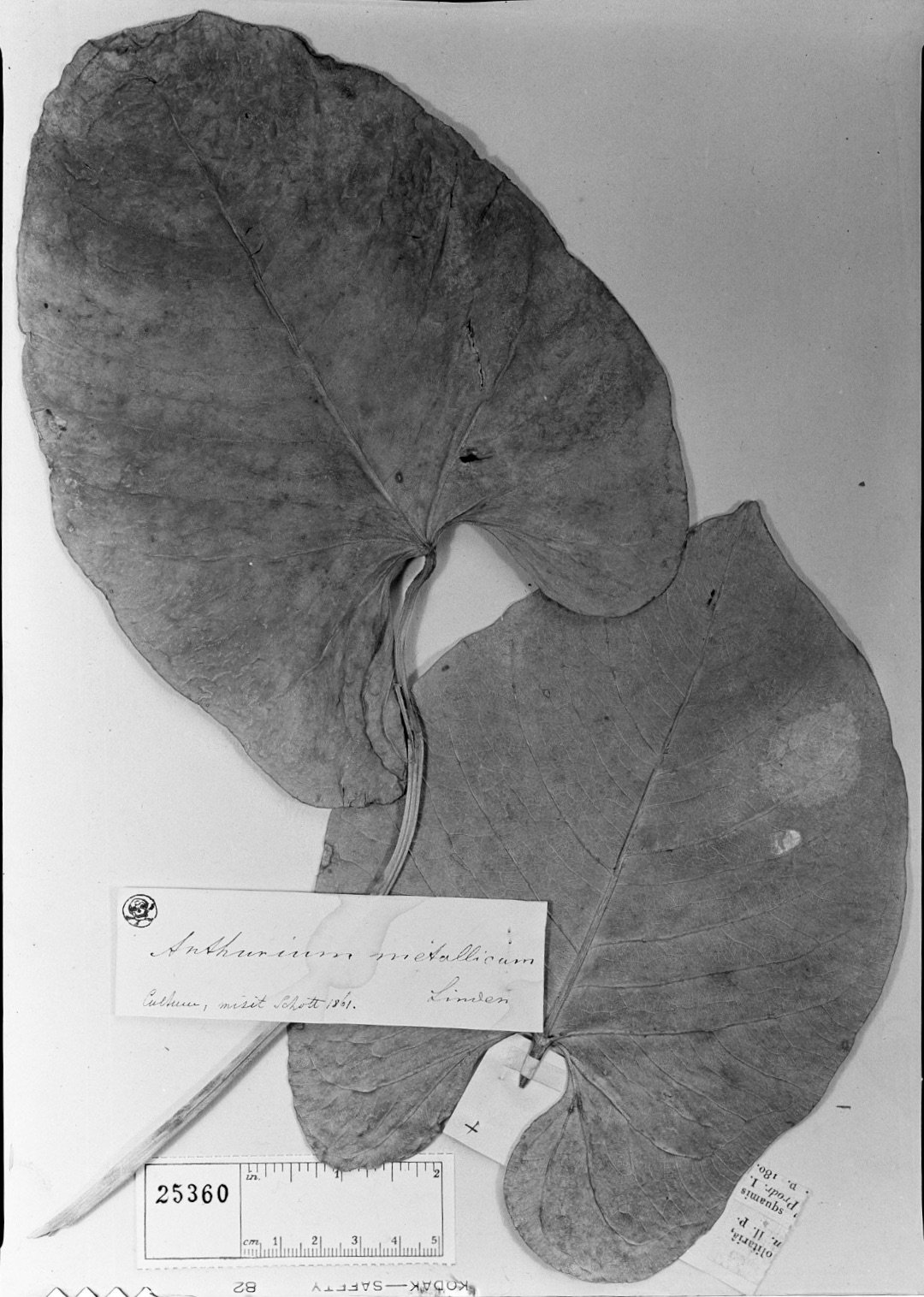

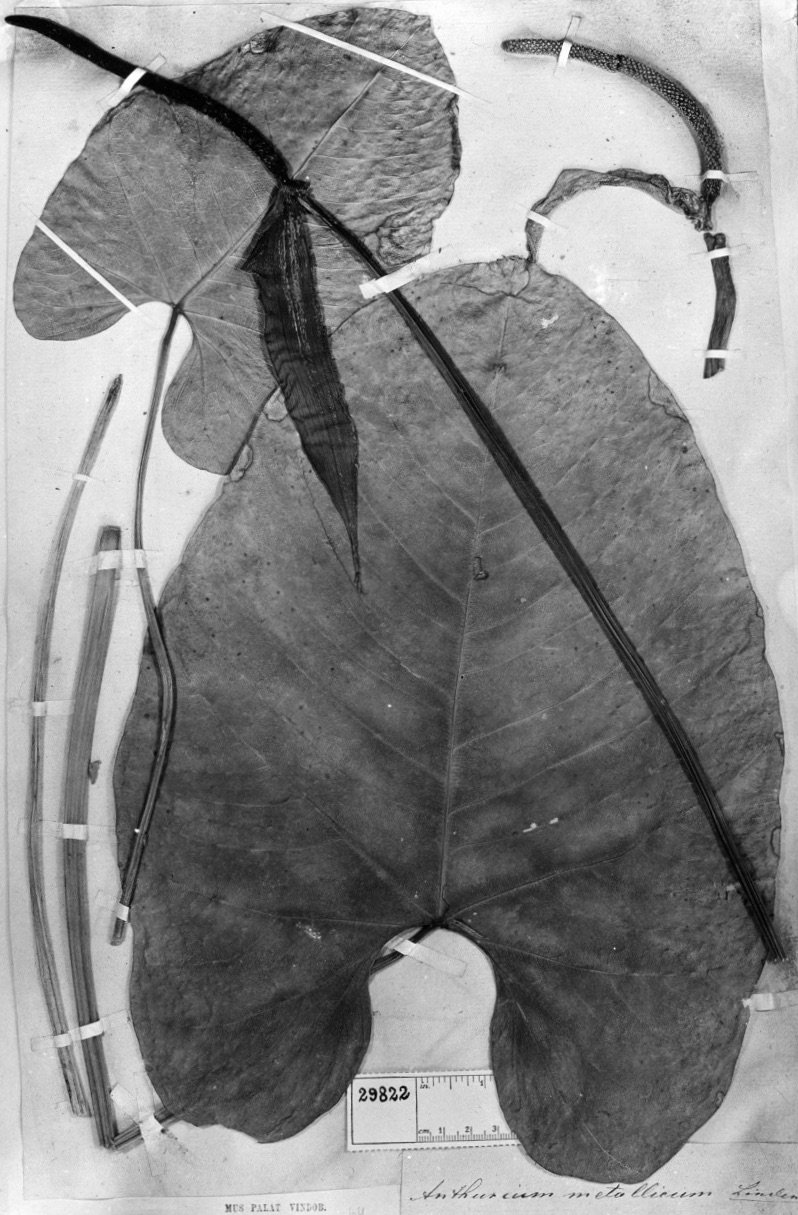

While searching for other 19th century paintings of this species, I recently came across two excellent images of preserved specimens labeled Anthurium metallicum sent by Schott to the Vienna and Geneva Botanical Gardens in 1861.

One of the sheets is annotated “cultives, misit Schott” = “cultivated/of agriculture, sent by Schott” + Linden so this provides clear evidence of its provenance. Since there are at least two duplicates from this series deposited in the herbaria of the botanical gardens mentioned, these sheets presumably represent what Schott actually visualized as Anthurium metallicum. A cursory inspection of these specimens with cordate-suborbicular leaves as well as elongated (winged?) petioles and peduncles shows that they bear little resemblance to either the plant illustrated by Schott (again, fide T. Croat), nor the specimens that were cited by Jácome & Croat to base the rediscovery claim on in their 2005 article (see image above). I conclude that it is likely that Schott mistakenly labeled an illustration of a plant with elongated leaves and contrast veins in his monograph “Anthurium metallicum”, and that the plant depicted in his color plate is an orphan.

Given the confusion apparent in the written description and the discrepancies between Jácome’s plants from Tequendama, the plant shown in Schott’s color illustration, and these images of Schott’s preserved material, at least until molecular analysis tools are brought to bear on this question, it seems unlikely that we will ever determine what Anthurium metallicum really is. Because of this I disagree with the commonly held view that the array of giant, hemiepiphytic Colombian section Cardiolonchium species with contrast leaf veins, short, upright, or pendent peduncles and green spathes and green or dark gray spadices should be called “Anthurium metallicum” simply because it is a convenient name.

*

The remainder of the article will provide notes on what I consider to be the most noteworthy giants in the genus Anthurium, with plant sections and the species within them listed in alphabetical order. Cultivation recommendations on how best to grow and maintain them follows species-specific commentary.

I offer a tossed warocq salad as an appetizer. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Selections

Section Andiphilum

Anthurium fredmulleri Vannini & Croat. Leaf blades to 4.9 ft/150 cm in length in the description. Terrestrial or lithophytic in the vicinity of shaded streams, which it may sometimes root into. Narrowly endemic to a small, undisclosed area in northern Central American foothill cloud forest. This is the largest known Anthurium species with cordate or sagittate leaves that occurs north of Colombia. A handsome and surprising recent find in an area long known by local researchers for concealing noteworthy, microendemic flora and fauna. Small numbers of A. fredmulleri are known to be in cultivation in the U.S., sourced almost entirely from collections made at the time of the original discovery about five years ago. Plants that I have grown from seed were fast and relatively straightforward to succeed with to about 18”/45 cm leaf size but have proven increasingly unforgiving of even trivial cultivation errors in my hands as they mature. Flowering plants require cool nights, shady spots, oversized and vented containers filled with mineral based substrates, copious watering, and plenty of food. Like other large members of section Andiphilum their berries take well over a year (likely almost two) to ripen fully. The relationship of A. fredmulleri with other members of section Andiphilum is still a bit unclear. Its short inflorescences and long, thick, almost woody scaffold-type roots are largely an exception among regional Anthuriums other than the dissimilar looking A. castillomontii Croat, Vannini & Hormell from eastern Guatemala.

On the left, Fred Muller with his namesake growing in nature, and a spotless and breathtaking fully mature leaf on the right. Note inward-turned basal lobes facing each other. Anthurium fredmulleri is superficially similar to, but only distantly related with, some of the giant esqueletos from western Colombia. In my admittedly biased opinion, when well grown it is the most attractive Anthurium species in Mesoamerica. Images: ©Fred Muller 2024.

A pair of young seed-grown Anthurium fredmulleri in my collection in California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

The scaffold roots on larger Anthurium fredmulleri are rigid and atypical for Mesomerican species. Escaped from the confines of their baskets in search of the nearest stream, they can attain impressive lengths (>7’/215 cm) in cultivation and even greater lengths in nature. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Fresh inflorescence on a cultivated Anthurium fredmulleri. The peduncles are mostly less than 6”/15 cm long and are sometimes almost nested in the center of the plants. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Anthurium titanium Standl. & Steyerm. Leaf blades to 3.9’/112 cm in length in the description; cultivated and wild plants observed by me very near the type locality to 4.5’/135 cm. Terrestrial or lithophytic in middle to upper elevation cloud forest. This is the second largest known Anthurium species with cordate or sagittate leaves occurring in Mesoamerica and Panamá. Native to the western Guatemalan Volcanic Cordillera and adjacent Chiapas State, México on the Pacific versant. A recently discovered disjunct population from Gulf slope cloud forests in western Guatemala is believed to be conspecific and is treated as such here. It is unlikely that anything other than tiny numbers of type locality material from San Marcos Department, Guatemala are in cultivation but there are quite a few plants from the new population being grown in California from seed. Some plants from southeastern Chiapas may also be grown by collectors in México. This species is an excellent candidate for trials in shady, wind sheltered beds in coastal areas with mild climates on the US west coast and should prove cold tolerant to near freezing. Despite being confused in the past with Anthurium faustomirandae Pérez-Farrera & Croat, they belong to different sections and inhabit very distinct ecosystems.

Anthurium titanium growing as a terrestrial in cloud forest, western Guatemala. Leaves shown ca. 3’/92 cm; exceptional examples of this species can be up to 50% larger further south. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Leaf detail on a cultivated Anthurium titanium from the type locality growing in my collection in Guatemala. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Developing infructescence on a wild Anthurium titanium. Fully mature, this structure will exceed 12”/30 cm in length. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

To continue reading the rest of this and other Premium Content articles, please subscribe to Esotérica Exclusiva.

Access to deeper dives and behind the scenes looks into advanced tropical horticultural practices as well as observations on fieldwork, plant collection management, and Neotropical wildlife.

Acknowledgements

Best friend, Bogotá resident, and fellow Esotérico Peter Rockstroh generously hauled my battered chassis around the rugged western slope of Colombia’s Central Cordillera in March 2024 to scout for interesting Anthurium populations inhabiting the megadiversity cloud forests there. That trip proved the catalyst to finally put this article together. Peter also clued me to the confusion surrounding the identity of Anthurium “metallicum” a few years back. Eco-tour guide and photographer Fred Muller provided valuable images of Anthurium queremalense, A. fredmulleri, and A. faustomirandae in nature. Ron Parsons shared a photograph of A. sanguineum at the type localitity, together with others showing wild hybrids between this species with some of its neighbors. Dr. Thomas Croat of the Missouri Botanical Garden has always provided an informed sounding board for me to bounce theories off and is a ready and matchless source of expert opinions on all things Anthurium. I generally defer to his unequaled expertise with the genus. Botanist Juan José Castillo of the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala has been a frequent field companion over the decades and has always brought his formidable knowledge of Mesoamerican flora and wry humor along for the rides. Chris Hall and Dr. Arden Dearden have been generous in sharing artificially propagated seed and their own experiences growing giant Anthurium species in their collection in northern Queensland, Australia. Arden was also an early prod for attempts to sort out the identity of the “Henckle Anthurium” discussed above, which have only shown recent progress this year. Panamanian aroid researcher and wildlands conservationist Ramón de la Peña very kindly shared his valuable observations on the impacts on drought stressed Anthurium species during the 2023-2024 El Niño event in that country. Ramon’s wide-ranging studies and resulting insights into the ecology of native Panamanian aroid communities are a welcome breath of fresh air and deserve duplication by resident scientists and naturalists elsewhere in the Neotropics.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2024, ©Jay Vannini 2024, ©Fred Muller 2024, ©Ron Parsons 2024, ©Peter Rockstroh 2024, ©Juan José Castillo Mont 2024, and non-copyrighted Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0 DEED 2024).

A pair of fully mature and unrelated Anthurium nervatum from the type locality displayed front and center in my collection in California. Image: ©Jay Vannini.