The Pebbled-leaf Anthuriums

by Jay Vannini

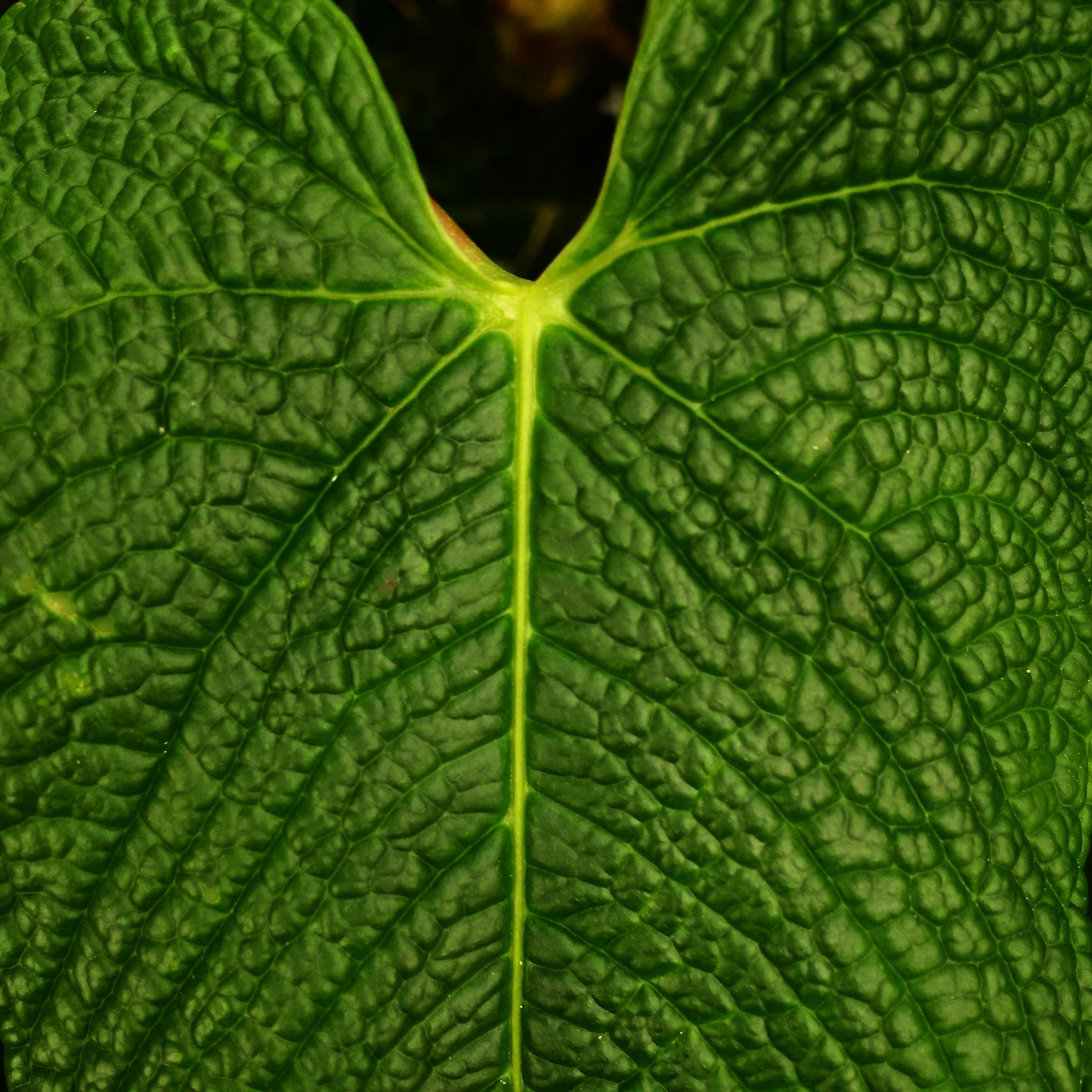

A very attractive dwarf terrestrial Ecuadorean Anthurium species aff. exstipulatum being grown in my collection in Guatemala. This species is somewhat easier to grow than the much larger true A. corrugatum (shown below in California) as well as the somewhat different A. exstipulatum. It stays compact with leaves to about 9”/23 cm long.

Bullate leaves occur in a very wide range of plant families, both in tropical ornamentals and familiar temperate species such as primulas, nettles and some asters. Bullate is generally defined as “blistered”, “bubbled” or having semi-globular swellings. Since we are discussing leaf structure specifically, I would add “pustulate” and “pebble-textured” to the list. This feature adds considerable visual appeal to foliage, and many popular plants in horticulture show it. The common explanation for this adaptation is that it, a). increases the ability of the leaf to capture light from all directions by increasing total surface area and, b). repels water/facilitates quick drying of a leaf surface via channeled drainage. Both enhancements are of obvious value to plants growing in the low light, almost perpetually wet environments of tropical rain and pluvial forest understories. Accepting this as a reasonable hypothesis, it seems logical that species originating from tropical pluvial forests should show this feature in extreme form. There is a lot of evidence suggesting that this is indeed the case.

In tropical aroids, bullate leaves are an attractive feature of many genera. Among those commonly-cultivated, it is found with some frequency in Anthurium, Philodendron, Alocasia, Rhaphidophora, Arisaema, Anubias, Amorphophallus, Dracontium, etc.

Newly emergent leaf on a mature Anthurium luxurians in the author’s California collection. This is a beautiful, if very slow growing species in cultivation. It is of great interest to anthurium breeders, and some of its hybrid offspring are very coveted by rare aroid collectors.

Anthurium debile in nature, lowland tropical pluvial forest in western Colombia. This is a challenging species for most growers and is very prone to decline in cultivation when conditions are not optimal. Image: F. Muller.

Many familiar anthurium species have bullate leaves, with quilting on the lamina evident to a greater or lesser degree. There are several quite well-known anthuriums in ornamental horticulture that have been cultivated since the late 1800s, including the justifiably famous Anthurium veitchii. Many recently discovered section Belolonchium species from the Andean countries also have markedly pleated leaf lamina. Others, like the odd-looking A. reflexinervium from section Pachyneurium, are relatively recent introductions to tropical plant collections. Beyond just having distinctly waved, rippled or bullate leaves, there is a subset of approximately 20 species and hybrids that are remarkable for the degree to which their leaves have also added distinctly micro-papillose upper surfaces in response to microenvironmental pressures in native habitats. None can be characterized as common in cultivation, although a few are usually available on an irregular basis by nurseries that specialize in rare aroids.

Anthurium cutucuense, 5'/1.60 m tall plant grown in Guatemala

These species include:

Anthurium luxurians, A. splendidum, A. giraldoi, A. kunayalense, A. debile, A. rotolanteanum, A. lapoanum (All Sect. Cardiolonchium); A. corrugatum, A. bernalii, A. aff. toisanense, A. rugulosum (All Sect. Polyneurium); A. cutucuense, A. arisaemoides (Both Sect. Dactylophyllium); A. clidemioides, A. flexile (Sect. Polyphyllium); A. radicans (Sect. Chamaerepium); A. unense (Sect. Urospadix); A. silvigaudens (Sect. Andiphilum).

Noteworthy hybrids:

Anthurium luxurians x dressleri (J. Vannini), A. luxurians x papillaminum (ex-FL; J. Banta? remade by anon. in Australia, remade J. Vannini), A. luxurians x crystallinum (A. Dearden), A. luxurians x forgetii = A. Majestic (anon., Australia), A. rugulosum x warocqueanum (K. Havlicek; poss. reverse cross), A. radicans x luxurians (Selby BG, formerly in mass market TC mistakenly as A. radicans x dressleri Selby BG as well as another quite different-looking hybrid that was also made there four decades ago and remade by me in 2004) and A. papillilaminum x bernalii (J. Vannini). There are several promising novel hybrids from within this species group that I have made recently that are still at seed or seedling stage scheduled for limited release in 2020. Please refer to the images of A. Canal Queen and Quechua Queen shown below as well as the article on velvet leaf anthuriums on this site for images of some of the new crosses.

Leaf detail on a new young section Cardiolonchium hybrid of the author’s, Anthurium Canal Queen™ ‘Drake’s Ghost’. This clone is an interesting blue gray color and very bullate even in youth. Color in the hybrid varies from acid green to an even darker blue gray. This leaf is 14”/35 cm long, but I expect this clone to develop leaf blades to 24-28” in length at maturity.

While the true locational origins of a couple of the species listed above remain uncertain (i.e., some A. radicans-complex plants and A rotolanteanum sp. ined.), all the others all originate from extremely wet forests. Most are middle elevation to montane cloud forest plants, two of which occur as high as 3,000 m (9,750’) in the NW Andes. The remaining species are lowlanders that require shady, very warm, wet conditions year-round to thrive. Almost all are terrestrial, with four species and two hybrids growing as hemiepiphytes or true epiphytes.

These plants make superb additions to any tropical plant collection that can provide them with the conditions they require. Since the species mentioned originate from a range of ecosystems that vary from perpetually hot to quite cool climates, there should be at least a pair of species perfectly suited for most settings. From my own experience and comments by the few other people who have grown it, I would rank Anthurium splendidum and A. giraldoi as being by far and away the most challenging species on the list to cultivate and obtain and A. radicans being the easiest to grow and source. Whenever possible, locality data should be looked out for and paid attention to, since some of these species occur at wide elevational ranges that have obvious implications for their cultivation.

Anthurium radicans x dressleri

Anthurium splendidum mature leaf detail in nature, Tropical Pluvial Forest, western Colombia. Image: F. Muller

Anthurium splendidum in cultivation. When happy, arguably one of the most beautiful of all foliage aroids, yet also the most difficult to succeed with in captivity. Author’s plant and image/.

Anthurium lapoanum, a very showy terrestrial species from middle elevations in southern Ecuador. This is a very good form being grown in my collection in California.

Growing media is a subject of considerable debate among tropical aroid growers. I have experimented with a number of products and blends over the decades and have settled on either pure long-fiber NZ sphagnum for compots, small seedling and for re-rooting imported stems and a mix of approximately two parts fine Orchiata bark (Pinus radiata source), two parts medium Orchiata bark, one part coarse pumice or perlite, one part medium hort charcoal and one part medium tree fern fiber for plants once they go into individual pots. To this mix I add encapsulated gypsum at recommended rates per volume being prepared, dolomitic limestone at same rate, and a balanced formula prilled, slow release fertilizer, preferably Nutricote 180 or 270 day formulations “to taste”. For a few very delicate terrestrial species, I have also used mineral substrates and pure osmunda fern fiber with some success.

Anthurium kunayalense, new leaf color of a highly localized Panamanian Caribbean rainforest species that is extremely rare in cultivation. Live type specimen shown.

Wild Anthurium kunayalense, leaf detail. Image: F. Muller.

I am not really a fan of sphagnum peat moss as a substrate. Some public gardens, especially in the EU, have a zero-peat policy in response to valid criticisms raised by the “bog people”. While many nurseries, particularly in the southeastern US, still use sphagnum peat and perlite as a standard mix to grow ornamental aroids, I have always found it challenging to work with. Nothing new or clever to say about it, really. When soaked it takes ages to dry, and when fully dry it takes ages to wet. Unlike sphagnum moss, which can be sustainably harvested (but probably isn’t in most places), peat extraction is open pit mining. Peat certainly has its uses in ornamental horticulture but should certainly be used in a more rational manner and in FAR lower volumes than it is today.

Two relatively unrelated bullate-leaf Anthurium species from Neotropical cloud forests are shown above. Left, A. silvigaudens, a central Guatemalan endemic (Image: F. Muller). Right, A. rugulosum from Ecuador and Colombian high elevation Andean forests.

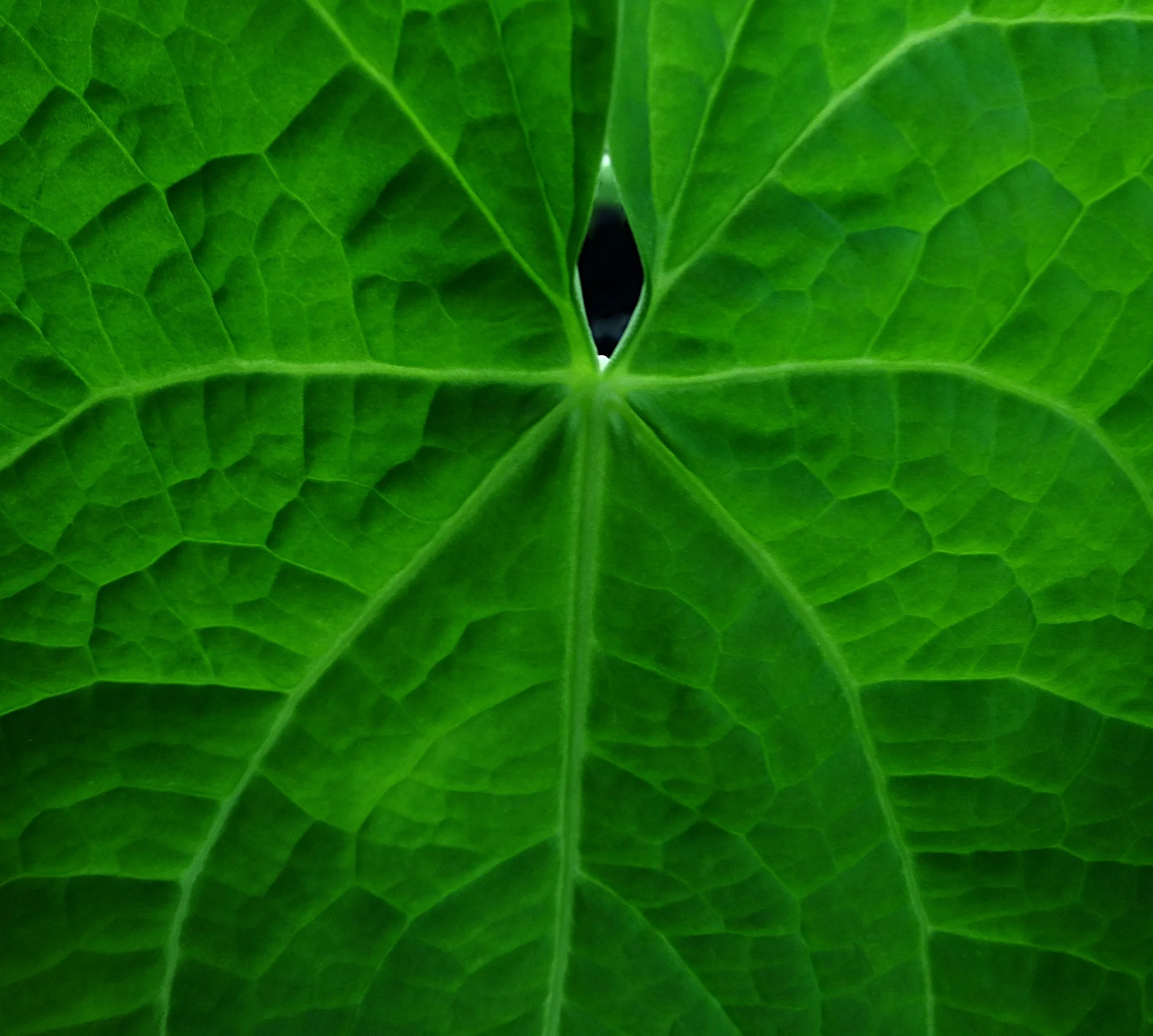

Two very showy upper elevation Ecuadoran Anthurium species from section Polyneurium in the author’s collection. Upper left, the tall, upright hemiepiphyte A. aff. toisanense and right, the terrestrial A. corrugatum. Both of these plants require cool night-time temperatures, excellent drainage and good water quality to develop and maintain perfect leaves like these in cultivation.

Anthurium rotolanteanum (sp. ined.) is a very showy, warm growing section Cardiolonchium that shares a number of leaf traits with its larger, distant relation from upper elevation cloud forests of the NW Andes, Anthurium rugulosum. Shown left is an image of a backlit large mature leaf of A. rotolanteanum in the author’s California collection to illustrate the complex vein patterns characteristic of many pebbled leaf anthuriums and right, a comparison of mature but unflowered inflorescences of A. rotolanteanum (L) and A. rugulosum (R) at approximately the same stage of development.

Leaf detail, author’s proprietary hybrid, Anthurium Quechua Queen™ (A. marmoratum ‘JW’ x A. rugulosum ‘Lago Agrio Road’. This unique hybrid combiness very pebbled, velutinous leaf surfaces with contrast primary veins and peacock blue or turquoise iridescence.

Anthurium radicans, large seedlings in a community tray in the author’s collection in Guatemala.

The epiphytes and hemiepiphytes on the list, especially A. clidemioides (above left) and A. cutucuense, should be provided with support of some kind. Options include narrow redwood or cypress studs, tree fern totems (now very costly but my preference still), virgin cork tubes, sphagnum moss-filled hardware wire tubes and coco fiber-wrapped poles.

Basic anthurium cultivation recommendations apply to all species. These plants do not respond well to root disturbance after seedling stage, they loathe anything stronger than a gentle breeze, and they prefer high humidity regimens no matter what their temperature preferences. In general, a shady environment is preferred. Higher light is tolerated by some species, but supplemental magnesium feeds should be added to offset the effects of higher light levels on the plants. Some species appear to be especially water quality sensitive, especially A. splendidum, A. debile and A. bernalii.

Above left, the southern Central American epiphyte, Anthurium clidemioides and A. silvigaudens from the central Guatemalan highlands (above right, image F. Muller).

Anthurium lapoanum leaf detail.

Two extremely beautiful bullate (sometimes bubbled when mature) leaf anthuriums are shown below in the author’s collection in California. On the left, the delicate and aptly-named, A. debile with blue-black leaves to >20"/50 cm from near sea level in the Colombian Chocó and Valle del Cauca Provinces, and my own hybrid on the right, the similar-size A. luxurians x dressleri (the ‘Black Magic’™ clone), that combines a very dark-colored pebble-leaf Colombian species with a very dark-colored velvet-leaf Panamanian one.

Anthurium cf. giraldoi, an upper elevation terrestrial species from cloud forests of the Colombian Chocó and Valle del Cauca Departments. This species began to show up in mixed commercial offerings of wild-source A. splendidum in 2019 and has also proven even more challenging in cultivation, despite greater tolerance to cool temperatures.

Anthurium sp. aff arisaemoides from the Cordillera del Condór, southern Ecuador. The leaves on this plant are substantially wider and more bullate than run-of-the-mill A. arisaemoides. Author’s plant and image.