The legendary fashion designer Mary Quant has passed away aged 93. The news was confirmed today by her family, who said that she died peacefully at her home in Surrey. Here, we revisit our feature celebrating the life and work of Quant, who was the subject of a fascinating exhibition at the V&A in 2019.

In an empty, darkened gallery in the depths of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, a succession of stylish women are taking turns to sit on a high stool, speaking to camera. A journalist, a model, a beauty expert and a customer, all from the epicentre of fashion’s 1960s revolution, are recording short films for the V&A’s sensational retrospective devoted to the designer Mary Quant. The quartet are united by their memories of the red-headed icon who popularised women’s trousers and tights, invented the skinny-rib sweater and the sack dress, and raised hemlines to audacious heights.

Listening to these fizzing, funny and often moving reminiscences feels like travelling in a Google Earth time machine, zooming in on the decade when Bazaar, Quant’s small shop in the heart of the bohemian King’s Road, formed the nexus of London’s ‘Swinging Chelsea’.

Here is the distinguished writer Brigid Keenan, an early champion of Quant’s designs. Here is Jill Kennington, one of the top models of her day, who, all legs and tousled hair, bounded onto a 1960s catwalk to a pop soundtrack in front of a cheering audience. Next up is Joy Debenham-Burton, once in charge of Quant’s pioneering cosmetics range, which came packaged in shiny PVC and imprinted with the designer’s trademark daisy logo, recalling a time when "the Beatles supplied the sound and Mary provided the look".

Finally here is Tereska Pepé, a committed early client who has donated two much-loved pieces to the exhibition, describing how she appeared in her favourite Quant outfits so often that they "fell apart on me even as I wore them".

Mary Quant graduated from Goldsmiths aged 19 in 1953, the year of the Queen’s Coronation, in a Britain still subject to wartime rationing. After a brief apprenticeship at the leading Mayfair milliner Erik of Brook Street, where she customised hats with her trainee-dentist brother’s curved incisor needle, Quant started to make her own practical, often waist-less, androgynous clothes in tweed, gingham, grey flannel and Liberty print, fabrics traditionally associated with men or with childhood. She fell in love with (and later married) her fellow Goldsmiths student Alexander Plunket Greene, a flamboyant, silk-pyjama-wearing charmer, and the couple quickly became the pivot around which the ‘Chelsea Set’, a cool nucleus of creative energy, revolved.

In 1955, together with their friend, the lawyer and photographer Archie McNair, the pair opened their club-like shop, which sold a bizarre and bazaar-like mix of Quant’s own (self-taught) designs and a varied collection of jewellery and accessories commissioned from their art-student friends. Drinks for customers enhanced the fun of browsing as duchesses jostled with typists and the thump of jazzs pilled out of Bazaar’s open door onto the pavement.

Passers-by stopped to stare at the eccentric window displays, where models adopted quirky poses, motorbikes serving as props. Suddenly, shop-ping had become as enfranchised as it was sexy. In the basement, a restaurant, Alexander’s, provided the meeting place for the in-crowd: for Princess Margaret and her photographer-husband Tony Snowdon; for movie directors, artists, writers, Rolling Stones, aristocracy, models, photographers; and, later, for Prince Rainier of Monaco and Grace Kelly.

The serendipitous synchronicity of a name shared by the shop and Harper’s Bazaar emerged just ahead of the opening of Quant’s Bazaar. In its September 1955 issue, this magazine became the first publication to feature a Quant editorial, printing a photograph of a sleeveless daytime tunic worn over culotte trousers, captioned "big penny spots on smart tan pyjamas, 4 guineas, from Bazaar, a new boutique". Although Quant described her spotty pyjamas as ‘mad’, Bazaar, with its uniquely agile finger on the social pulse, was alert to her potential.

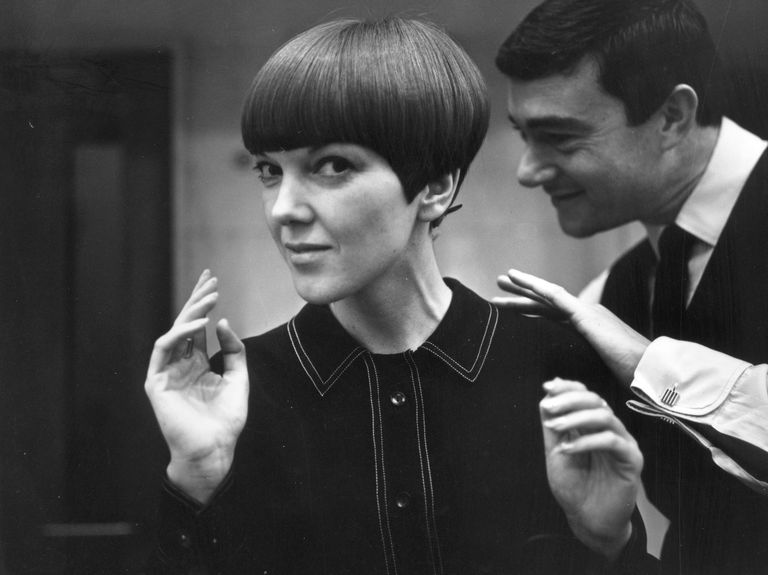

Barely an issue went by without her clothes being featured in the magazine and, in July 1957, Bazaar ran the first ever profile of the designer. She was photographed in "offbeat shades of violet and blue, with cream, black and string', shortly before she asked Vidal Sassoon to shape her shoulder length, conker coloured hair into his distinctive, swingy five point bob. Quant’s highly individual style, reflected in her unusual name with its associated ‘quaintness’,made her the figurehead of her own brand, even when, paradoxically, her nonconformist outlook was by its very nature ‘anti-brand’.

The story of how the Quant influence became global underpins the V&A exhibition, which spans two decades from 1955 to 1975 and includes over 120 original garments, alongside personal photographs and objects. Although the designer herself has said she was unaware "that what we were creating was pioneering", her achievement was to upend the staid conventions of postwar austerity, when the young dressed like the old, transforming them into a celebration of youth, fun, accessibility and infinite possibility. In Mary Quant (£30, V&A), the gloriously full colour book that accompanies the exhibition, the senior curator Jenny Lister describes the speed with which Quant was singled out as typical of the 1960s mood.

In 1957, her second shop opened in Knightsbridge; in 1962 she agreed a deal with the American chain store JC Penney; in 1963 she launched her cheaper wholesale line the Ginger Group; and in 1966, her divinely packaged makeup, jewellery and coloured tights hit the stores. But it was the arrival of her miniskirt in 1965 – ‘so short,’ she said, ‘that you could move, run, catch a bus, dance’ – that ensured Quant’s position as the most sought-after label for every fashionable female.

In that year, I was a 10-year-old living on the King’s Road. Bazaar was en route to the Peter Jones haberdashery department and, looking longingly at the ‘far out’ window displays, I would implore my mother to take me into the shop. But she felt neither young, rich, hip nor brave enough to go in, marching me on towards her own safety net of name tapes and respectability. Youth was setting the pace, and by the end of the decade thousands of young women all over the world had been Quantified.

Fashion was not the only indicator of the 1960s ‘youthquake’, as identified from across the Atlantic by the legendary Diana Vreeland. The bright focus of enterprise had suddenly swung away from theUnited States, from Elvis, Cadillacs and blue jeans, illuminating instead Liverpool, London and specifically Chelsea. In 1961 the contraceptive pill became available on the National Health (but only supplied to married women, hence the appearance of brass curtain rings on many left hands).

The same year saw the launch of Private Eye, just as a cult of satire swept

through clubs, television and the press, challenging old political, social and sexual certainties. In her 1966 autobiography, Quant emphasised that women’s clothes should be "a tool to compete in life outside the home", reminding her readers that this exhilarating whirlwind was undercut by a deeply serious, emancipated intent. "The young intellectual has got to learn that fashion is not frivolous; it is part of being alive today," she wrote.

The V&A holds a substantial number of iconic Quant designs in its own collection, including standout dresses donated by the sisters Carola Zogolovitch and Nicky Hessenberg. Zogolovitch’s still covetable grey tweed shift was a 21st birthday present from her father, the architect Hugh Casson– a man with his creative ear to the ground –while Hessenberg’s mother persuaded her reluctant daughter to attend stuffy debutante parties with the bribe of a drop-waisted cocktail dress in purple Thai silk.

"Only a dress from Bazaar could do the trick," Hessenberg remembers. Last year, in preparation for the Quant show, Jenny Lister and her co-curator Stephanie Wood put out a nation wide appeal to fill the missing gaps in their archive, inviting women who had worn the designer’s radical creations to check "attics, cupboards and family photo albums". They were inundated with offers of Quant clothes that had come to represent biographical milestones.

My own daisy patterned tights, black PVC mackintosh and, to use a BBC executive’s tuttutting 1958 term, ‘very abbreviated’ skirt – all 12th birthday presents – felt as transformative as the music on my tiny record player. While I belted out ‘Satisfaction’ into my hairbrush microphone and dabbed my eyelids with prune coloured eyeshadow from my Quant Paintbox, the combination of the Stones and Quant eased my transition into an adult world very different from my mother’s.

For me and countless others, the designer’s legacy remains a fundamental part of the 20th century story of women’s emancipation and the democratisation of fashion.

This article was originally published in the May 2019 issue of Harper's Bazaar UK.