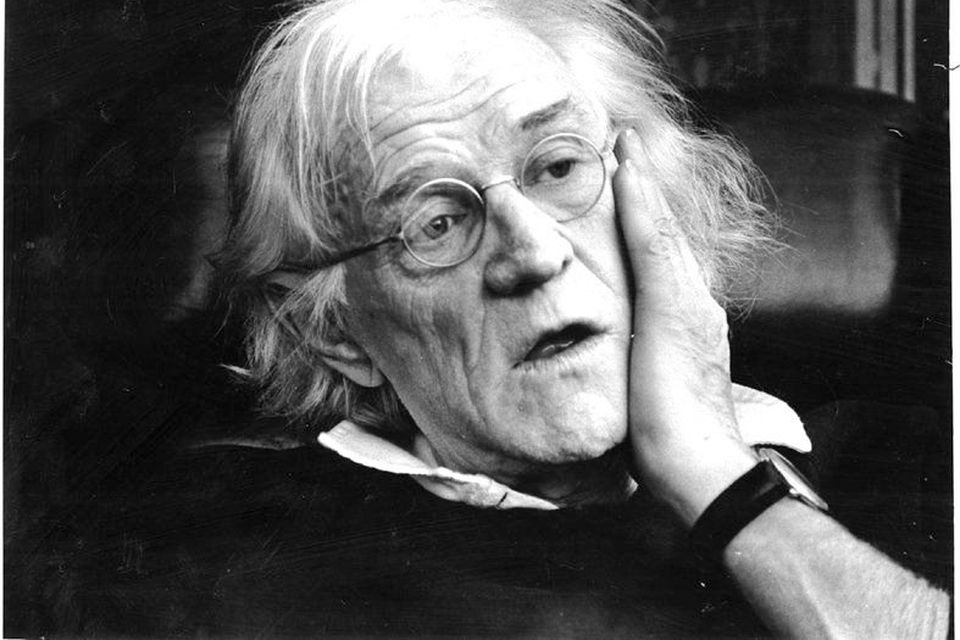

Remembering Richard Harris - Bull, bard and boozing silverscreen superstar

Richard Harris, who died 15 years ago this week, delivered as a gifted artist and hell-raiser

Richard Harris was 60 years old when Jim Sheridan asked him to play the role of the intimidating and short-tempered Bull McCabe in The Field. The film was shot in the beautiful but rugged Connemara; a suitable location for a star whose face was once described as "five miles of bad Irish country road".

"He was a big fella," recalls Padraic Coyne, owner of The Carraig Bar, Leenane. "Not very muscular now but a big tall man. Rough looking, and he acted like that in the film. Behind that, he was gentle enough. He was a down-to-earth fella and liked the funny side of everything."

Harris would be nominated for an Oscar for his portrayal and although he lost out to Jeremy Irons, it was the start of a career renaissance.

"It was really like he was waiting to play the role all his life," says co-star Joan Sheehy, who played one of the tinker women in the movie. "There were so many big scenes, the fair scene or the auction, so you had interaction with him every day and he was larger than life. I think with the white hair and the white beard and the huge coat it was hard to separate him from the Bull.

"We shot some scenes in some pretty inclement weather," continues Sheehy, "and my big memories of him are of when we might be up on the cliff and he'd be sitting on this single chair waiting for his scene. It was almost like God in the Catechism; this man on the side of a hill sitting there overseeing everything. He was from Limerick and so am I, so I was fascinated to hear those Limerick sounds in him, even after all those years away. As an actor, he was very purposeful, very anxious to get it right."

After The Field, Harris was offered roles in Unforgiven (1992), Gladiator (2000) and most bizarrely as Albus Dumbledore in Harry Potter, a role he initially turned down but then accepted because his 11-year-old granddaughter told him she would never speak to him again if he didn't.

There is a sweet irony in the thought of a man noted for his bloody-mindedness paying heed to an ultimatum delivered to him by an 11-year-old girl.

Harris loved acting but quite often did not get along with actors.

Not long before his death, 15 years ago on October 25 2002, he told a reporter from the Daily Mirror that he had "no friends in this business".

"I don't go to their clubs, don't go to their hangouts and don't mix at all," he added. "I am part of the business but I am apart from it."

When he reached what he saw as the unexpected milestone of 70, he took delight in being old enough that he could "be eccentric and get away with it". His residence at The Savoy Hotel in London, was costing him a fortune but, as he quite rightly pointed out, there were people paying mortgages who couldn't call someone at four in the morning for a sandwich. He could and he did.

Not that he let the apparently excellent service get in the way of a good joke.

"It was the food!" he bellowed as he was wheeled out of the hotel for the last time. It wasn't. It was in fact Hodgkin's Lymphoma.

Richard Harris had been getting away with it for a long time both on-stage and off. Even as a young actor he could be challenging to work with - not that it was always his fault.

Charlton Heston, with whom Harris co-starred in the 1965 western Major Dundee recalled that he was "very much the professional Irishman, and an occasional pain in the posterior". Harris thought Heston "square".

On day one of shooting for the 1965 classic The Heroes of Telemark, Kirk Douglas and Harris squared up to one another.

"Are you going to be as difficult as they say you are?" asked Douglas.

"Are you going to be as big a bastard as they say you are?" came the Irishman's response.

It didn't end there according to David Weston who had a bit part in the movie.

Seeing the arrival of a ship to be featured in the movie, Douglas, who had served for four years in the US Navy, gazed at it scornfully.

"What kind of ship do you call that?" he asked.

"A f***ing aircraft carrier," Harris replied. "In America they're twice that size... because they have to carry twice the amount of shite."

There were petty squabbles over who had bigger and better cars to courier them to the set and according to Weston at one point it came to blows. Eventually however Harris and Douglas would become firm friends. Douglas was instrumental in getting Harris the lead part in the 1967 musical Camelot opposite Vanessa Redgrave.

Harris did all he could to land the role. According to one story, he even hired a man to walk up and down The Strand in London carrying a sign which read: "Harris Better than [Richard] Burton, Only Harris for Camelot." At one point, he sent a note to producer Jack Warner, just to inform him that Vanessa Redgrave was 5'10", the same height as Burton while he, Harris, was a towering 6'2".

He got the part and went on to win a Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Musical or Comedy.

Harris was cheeky, irreverent, funny. According to him he had to be, to be noticed. He was born into a family of seven siblings in Limerick. From day one, he was battling for attention.

"I was lost in the middle of the Harris brigade," he told journalist Joe Jackson in 1987. "But this makes you fight for the affection of your parents, fight for their attention. You don't get it for free. You get it from the age of one day to two years; then have to fight for it. You had to put up a flag and say, 'Hey, I'm here, too, don't miss me', or you were passed over."

His family were well off. His father owned flour mills in the city where Harris would later work as a rat-catcher. In a 1973 interview, he informed Michael Parkinson that he didn't last that long because he organised a strike for the workers "against my own father".

By his own admission, he was never good at school but was always interested in sports, especially rugby, a game he had to quit in late adolescence when he contracted tuberculosis.

Consumption confined him to bed for three years, he claimed, but during this period he started to read. As people stopped coming to visit, he had to make up friends to keep him occupied and thus he started acting in his sick bed.

"I used to invent people out of light bulbs," he said. "I'd come up with hundreds of conversations with people in light bulbs, and these hundreds of people would come in and I'd be the king of England or the Pope and that's how it started."

After recovering from his illness, he went to London and entered the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, to study acting. It was, he said, a "period of starvation" during which he spent six weeks sleeping in a coal cellar. In 1956, then aged 26, he joined the Theatre Workshop run by Joan Littlewood.

"Everything I know or everything I'm supposed to know about acting," he later said, "I learnt from this marvellous lady."

Harris appeared in a production of Brendan Behan's The Quare Fellow at the Theatre Royal in Stratford. He was seen there by Lee Strasberg, then the director of the Actors' Studio, who found him impressive.

A small part in the 1961 war classic The Guns of Navarone, starring Gregory Peck, was followed by a strong supporting role as mutineer John Mills in Mutiny on the Bounty, which starred the superb but supremely difficult Marlon Brando. Harris was a fan but by the end of filming that had changed. In one scene Brando's character, Fletcher Christian, strikes Mills. On the first take, Brando's attempt was a damp squib. Harris responded with a mock curtsy but Brando didn't get the joke. After a similar effort on the second take, Harris thrust his chin forward and said, "Come on, big boy, why don't you f***ing kiss me and be done with it!" Harris kissed Brando on the cheek, hugged him, and asked him to dance. The lead man's ego had been dealt a blow and he stormed off the set.

A year later the Limerick man was nominated for an Academy Award and won the best actor award at the Cannes Film Festival for his gritty portrayal of rugby league professional Frank Machin in This Sporting Life.

By now, Harris had been married to Elizabeth Rees-Williams for six years. They had met as student actors and fallen in love. Nine days before accepting what turned out to be his greatest accolade at Cannes, the couple's third son, Jamie, had been born. He and his brothers, Jared and Damian, would go on to have successful careers in the movie industry themselves but Harris's career with all of its associated indulgences took its toll on the marriage and eventually the couple divorced in 1969.

"Elizabeth says in her book that I beat her, once or twice," Harris told Joe Jackson in 1987. "I probably did give her a smack across the face. I remember once I did. This was unjustified. It was horrendous. I once asked Elizabeth, 'What was I really like to be married to?' She said, 'It was absolute magic, a magic carpet ride, but then one day you'd get that look in your eyes, one drink too many, and in the end, I couldn't take it, the good moments weren't balancing out the bad'."

While Harris was away filming Camelot in Los Angeles, she filed for divorce.

Years later he married Ann Turkel but that too ended in divorce. He remained good friends with both women.

Tales of Harris's nights out are of course legendary. Along with his great friend Peter O'Toole, as well as Oliver Reed, Albert Finney and Richard Burton, he raised hell in the bars of London and the town he referred to as the glue pot, Dublin - "once you get in it you can never get out".

One night during a theatre run with Peter O'Toole in The Old Vic in Bristol, the pair were late for their cue due to an impromptu break taken in a bar across the road from the theatre. Having dodged traffic and made it back to the auditorium, the pair rushed to get on stage.

"[There was] a pause on stage," Harris later told Conan O'Brien. "I dashed on, tripped over a wire, slid right across the stage, right down on to the footlights and hung over on to the lap of two or three Bristolian old women. This woman looked at me in shock as my head was in her lap and she said out loud, 'Good God, Harris is drunk'. And I said to her 'Madam, if you think I'm drunk, wait until O'Toole makes his entrance'."

Years later and after quitting alcohol, Harris received a note while on tour in Yorkshire with the theatre production of Camelot. He had bought the rights to the musical and made a fortune from touring it. The note had been sent by a local family with whom Harris had spent several nights. Nights that he could not remember, he said. On reacquainting themselves with Harris they informed the actor that he had come to them via London.

"I had been kicked out of a pub," recalled the actor, "so I figured I'd get another drink on a train. So I got on a train and got off at a stop that was Leeds. It was very late and I saw a light in a window so I threw some pebbles up. And this woman came and said 'What you want?' I said, 'Can I have a drink?' She recognised me and I think I spent about four days there and I don't remember them at all."

On one occasion during a newspaper interview with a reporter in the US, he boasted that whenever he landed in New York he headed straight for a bar on Third Avenue where Vinny, the barman, would line up six double vodkas the moment he walked in. When challenged on the veracity of the story, Harris called a taxi to drive the pair to Third Avenue and the bar in question.

As soon as Harris walked in through the door he caught the barman's eye and seconds later, six double vodkas appeared on the bar.

There were long weekends and fights, and some nights were spent in cells.

In 1970, he appeared in the cult classic A Man Called Horse but the trajectory of his career took something of a nosedive, at least on the big screen. Gulliver's Travels (1977) and Tarzan, The Ape Man (1981) were particularly poor choices. By the late 1970s, Harris was taking cocaine. He claimed it helped him come off the booze. It didn't and one day he woke up in a Los Angeles hospital bed to find a priest looking up towards him holding rosary beads.

By 1981, he had had enough of what he called his "bacchanalian" lifestyle and he took the decision to quit.

"It's a very different life," he told Michael Aspel in 1987. "I find I live a lot to myself now. I used to be very gregarious before I suppose, not knowing who I was with…"

But to focus solely on Richard Harris as a hell-raiser would be to do him a disservice.

As well as his acting, Harris wrote poetry. His first wife, Elizabeth, remembers hearing it on their first date and recalled how he used to write poems on cigarette boxes and ask her to keep them. Harris was also a useful singer, more soulful than technical. In 1968, he released the album A Tramp Shining which included the song MacArthur Park, a top 10 hit in the UK and US.

But he will and should always be remembered as one the finest actors this country ever produced.

"He had that big acting style which was fabulous to watch," recalls Joan Sheehy. "It was one of those times when you meet a star and they don't disappoint."

RICHARD HARRIS: SEVEN OF THE BEST

* The Guns of Navarone (1961)

A British team is sent to cross occupied Greek territory and destroy the massive German gun emplacement. Harris's impact is short but sweet.

* Mutiny on the Bounty (1962)

Harris, as the less-than-cultured 'second' mutineer, is an excellent foil to Brando's worthy Fletcher Christian.

* This Sporting Life (1963)

Arguably his best performance as a lead, Harris weaves between different societal roles with great skill.

* Camelot (1967)

A role Harris was very proud of. Critic Roger Ebert wrote: "Harris is a convincing king. Better still, he's a human king."

* The Field (1990)

Harris's portrayal as the irascible farmer should have won him an Oscar.

* Unforgiven (1992)

When Clint Eastwood phoned him to play the role of English Bob, Harris was at home watching High Plains Drifter (starring Eastwood). Harris thought it was a prank. Just as well he didn't hang up.

* Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (2001), Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)

Though emotionally blackmailed into the role of Albus Dumbledore, he played a blinder and gained a whole new audience.

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news