Fred Radtke, who conducted a quarter-century-long fight against graffiti in New Orleans, died on Aug. 24 of natural causes, according to a death notice that appeared on NOLA.com on Tuesday, Feb. 15. He was 76 years old.

Radtke was born in Pennsylvania, played on his high school football team and was a member of the U.S. Marine Corps. In New Orleans, he made a living as a festival coordinator. In 1997, he founded a nonprofit organization called Operation Clean Sweep, which sought to eliminate illicit aerosol painting from the streets of New Orleans. To do so, he often covered it up with a concrete-toned paint that gave rise to his superhero-style nickname, the Gray Ghost.

To those who believed graffiti was a blight, a source of public obscenity, a symbol of gang territorialism, or even Satanism, the Gray Ghost was a tireless gladiator. But his zeal for eradicating street painting made him a villain among those who saw graffiti as an artistic avenue of personal and political expression.

Anytime, anywhere

With a few faithful assistants at his side, Radtke was known to blot out all evidence of unauthorized spray painting for blocks on end, leaving behind a trail of gray erasures like the exhaust of a freight train.

Radtke viewed tags — a term for stylized graffiti signatures — as a signal of decline.

“It’s intimidating,” he said in 2001. “It shows neglect of a neighborhood, and gangs pick up on that. If graffiti stays up, it means nobody is looking out for the area.”

Richard Eric paints over graffiti around the S Carrollton Avenue underpass in New Orleans, La., Tuesday January 31, 2016. Operation Clean Sweep, ran by Fred Radtke, is on a mission to eliminate and prevent graffiti in the city of New Orleans with a response team and graffiti hotline.

In a 1997 interview, Radtke explained that his blotches of gray paint accomplished more than obfuscation; they were an antidote that told graffiti writers “there’s a force out here working against them.”

The Gray Ghost claimed he and his crew would climb to any height or endure any danger to remove tags.

“If they go up 10 stories, we’ll go 50,” he told a Times-Picayune reporter 20 years ago. “We’re not afraid to go anywhere. Our motto is: “Anytime, anywhere.”

Eliminating 10,000 tags

In the same 2001 interview, Radtke explained that he got his first taste of anti-graffiti activism in 1986, when he became disgusted by taggers who vandalized the wall of New Orleans' Greenwood Cemetery. Radtke said that when he painted over their inscrutable signatures, the taggers immediately came back and added new hieroglyphics. But after Radtke made it clear that he planned to return as often as they did, the graffiti writers eventually gave up.

Inspired by his triumph, property owners and others appealed to him to eliminate graffiti at other sites. Roller in hand, Radtke obliged, eventually becoming the city’s go-to graffiti fighter for hire. He successfully campaigned for the courts to levy stiffer fines for aerosol vandalism and offered rewards for the identities of anonymous graffiti writers.

“We have a historic city and some of the most beautiful architecture in the world, but a lot of these buildings are being ruined by graffiti,” Radtke said in 2001. “One of my goals is to help New Orleans on a national level.”

By 2006, Radtke claimed that Operation Clean Sweep had eliminated 10,000 tags and reduced the city’s illicit painting by 65%. Graffiti writers saw him as a nemesis and a rival, invoking his name like a real-life boogeyman. All graffiti eradication was attributed to the seemingly ubiquitous Gray Ghost, whether Radtke was responsible or not.

In the final version of Banksy's 2008 Clio Street painting, the graffiti eradicator has obliterated the entire sunflower.

Banksy versus the Gray Ghost

Radtke had become famous or infamous, depending on one’s point of view. So much so that the most famous artist in the world took notice. When the superstar British graffiti artist Banksy bombed New Orleans with several of his iconic stencils in 2008, he singled out Radtke for scorn.

In two paintings, Banksy depicted Radtke as a faceless, destructive personage, vindictively blotting out a buoyant graffiti sunflower and a terrified stick figure.

“I came to New Orleans to do battle with the Gray Ghost, a notorious vigilante who’s been systematically painting over any graffiti he can find with the same gray paint since 1997,” wrote the anonymous Banksy on his website. “Consequently, he’s done more damage to the culture of the city than any section (category) five hurricane could ever hope to.”

Banksy’s accusation was pure hyperbole, of course, but it may have signaled a change in attitude. The celebrity artist’s suite of Hurricane Katrina-oriented paintings seemed to be a gift to the city and may have stirred sympathy toward street art in general. Graffiti had long been fashionable in pop culture, but it gained particular cachet in the recovery-era Crescent City.

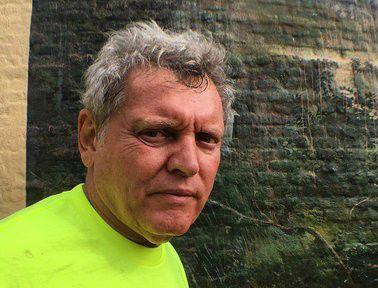

The Gray Ghost, Fred Radtke (Photo by Doug MacCash / NOLA.com The Times-Picayune)

But Radtke seemed to be an absolutist. He’d regularly proven that he did not distinguish between tagging and aerosol artistry. Nor did he always take the time to determine if a mural had been permitted by the property owner.

Once, he set out to paint over chalk drawings rendered by an artist who’d been commissioned to decorate the outside walls of the Contemporary Arts Center. Another time, he blotted out a graffiti-style mural on a Poydras Street warehouse that had been authorized by the owner. Radtke argued that the warehouse owner had not gone through the proper municipal channels to allow artists to paint his property.

The Gray Ghost’s combative impulses may have led to his ironic undoing.

Arrested for rolling

In October 2008, Radtke and Operation Clean Sweep volunteers began rolling gray paint over a large, elaborate, graffiti-style mural in Faubourg Marigny. Radtke was apparently unaware that the mural artists had been granted permission to paint by the owner of the wall. When the National Guard who patrolled the neighborhood during the post-Katrina recovery appeared, the Gray Ghost was arrested.

A judge sentenced Radtke to a 60-day suspended sentence for criminal damage to property. More importantly, the judge directed Radtke that, in the future, the anti-graffiti crusader was required to get property owners’ permission before painting over graffiti.

An Oct. 27, 2008 NOLA.com reported: “The Gray Ghost finally went too far. Fred Radtke, who has fought a zealous battle against graffiti in the Crescent City since 1997, was issued a summons for criminal damage to property Thursday night, according to New Orleans Police Department spokesman Bob Young, after Radtke and fellow activists painted over a mural that had been placed on a wall with the property owners' permission.” The upshot of the incident was that Radtke and other anti-graffiti activists were required to receive property owners’ permissions to blot out street painting. Radtke’s arrest reduced blanket graffiti erasure. So how did the Gray Ghost’s arrest save New Orleans? The combination of Banksy’s inspiration and the protection of permitted murals allowed for a new era of more refined, more expressive street art in New Orleans.

Radtke’s days as a graffiti remover for hire weren’t over, but his roving, no-holds-barred approach was certainly inhibited. Though he was still scorned and feared by street artists and their fans, the Gray Ghost was never quite the scourge that he’d once been.

But that doesn’t mean his actions did not prompt notoriety from time to time. In 2015, Radtke removed graffiti from a statue dedicated to Confederate Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, near the start of the city’s campaign to have such monuments removed. In 2017 he was hired to remove a huge tag from a 26-year-old farmers market mural in the CBD, a project that demonstrated that graffiti writers were as capable of defacing artwork as Radtke had ever been. In May, City Park commissioned Operation Clean Sweep to blot out all graffiti, leading to the ruin of remarkable works by street art stars Hugo Gyrl and Swoon.

Though Radtke might be seen as the opposite of a tagger, time and again, graffiti writers have pointed out that the Gray Ghost’s zealous actions were pretty similar to their own. Over the past 30 years, graffiti writers and the Gray Ghost were as mutually dependent as the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote.

Old Marines butting heads

Michael “Rex” Dingler, a street artist Radtke famously feuded with in 2008, has become philosophical about his old adversary. Dingler, who also served in the Marine Corps, said he and Radtke were "two crazy old Marines" having a "difference of opinion."

“Marines can get pretty stubborn,” he said. “When we feel a certain way about something, we stand our ground and rarely budge.”

Filmmaker Max Good, who included a depiction of Radtke in his 2011 film "Vigilante Vigilante: The Battle For Expression," affirmed that the Gray Ghost's "commitment mirrored the commitment of the graffiti writers and some of the guys recognized that."

In one of Good's video outtakes, Radtke explained that he was happy to have relieved city agencies, particularly NOPD, of the need to invest time and resources in graffiti removal.

"We've saved the police department 4,000 phone calls and took down 15,000 graffiti tags. That's what we've done. There's always going to be controversy, I can't help that. It's just the nature of the beast. We know what we've done and the majority of the people in the city know what we've done, and we're proud of that."

Radtke’s death took place in the days leading to Hurricane Ida and was not broadly known. Radtke is survived by his wife, Patricia; and his stepdaughter, Marlo.

Street art murals are like sandcastles at the beach. Nobody expects them to last forever. Still, the New Orleans artists who began painting a …

John Adam Hebert, an anti-violence advocate known for posting hundreds of plastic signs emblazoned with the word "LOVE" in public places aroun…

Artist Heather Mattingly was shocked when a man began blotting out her new mural on a utility box at Canal Street and Carrollton Avenue on Mon…