The coal was hot. The crew were ready. On July 3rd, 1938, the 4468 Mallard, an A4-class steam locomotive, was performing an alleged brake test for its London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) owners. What better way to test a new Westinghouse braking system than to run at speed—and then some?

With a veteran driver known for a steady hand at speed and a fireman known for his flying shovel, they set out on the U.K.’s East Coast Main Line, and the streamlined beast steamed away.

And away, and away yet, to the tune of 126mph, then a record for steam. And now (and perhaps forever) still a record for steam.

A Railway Magazine article of the time put it that “Mallard’s magnificent display fitly crowns the work which the LNER has done, both to demonstrate that coal is just as serviceable for high speed work as imported fuel in a diesel engine, and to rehabilitate the historic speed reputation of Great Britain.”

Steam was already facing extinction during its historic run, but the Mallard represented the perfection of the steam locomotive, the powerhouse that made the industrial revolution possible.

A Need for Speed

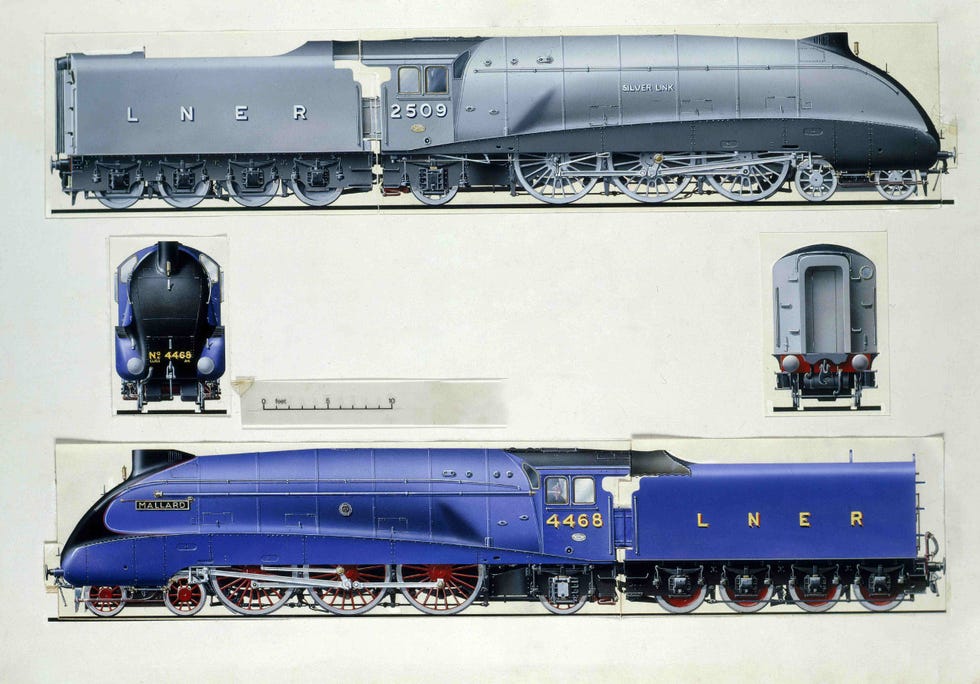

LNER’s Chief Mechanical Engineer Nigel Gresley had speed in mind when he designed the A4 “Pacific” locomotives.

Gresley had already designed some powerful steam locomotives earlier in the 20s and 30s, like the illustrious A3 Flying Scotsman—the A4s were the culmination of an impressive career in harnessing the power of steam.

The LNER had been in competition with its rival line, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS), for bragging rights on the competitive timings of their respective non-stop runs between London and Edinburgh. The need for speed was both motivation and inspiration in the design and building of the A4s.

“This was the era of speed records on land, sea, and in the air, and there was a general sense that life was speeding up, much helped by a new mass media—radio,” says Bob Gwynne, Associate Curator of the National Railway Museum in York, U.K., home of the 4468 Mallard.

The Mallard’s whooshing lines and dashing curves didn’t come out of thin air. It was the result of the 1930s Art Deco design movement crashing headlong into steam-locomotive technology. The Mallard’s streamlining owes a nod to the look—with those whipped curves—of some exquisite Ettore Bugatti racing vehicles of the period, such as the famed Type 43 and the 57C. The Bugatti-designed railway systems in France also influenced Gresley's locomotive shapes. Bugatti and Gresley were friends, and Gresley spent time in France surveying his work.

The Flight of the Mallard

The A4s were introduced in 1935 and all put in service for high-speed passenger lines. The A4s could take higher boiler pressures, had larger fireboxes, and more economical use of coal and water. With 35 built in total, the streamlined beasts were a big success—they were heralded for cutting the commuter time from London’s King’s Cross to Newcastle to four hours.

The first of the A4s, the Silver Jubilee, pulled by the Silver Link locomotive, “was a sensation when it was introduced,” says Gwynne. “The Silver Jubilee was a great commercial success, with a gross revenue up to six times its operating cost.”

But when the Mallard hit the rails three years later, it wouldn’t be your average, run-of-the-mill A4. No, the Mallard would come with a few engineering enhancements.

The first was its double chimney and Kylchap blast pipe, which “was a way of letting the locomotive breathe better, as it enabled the fire to be drawn through the tubes more effectively,” says Gwynne. “The other thing that Mallard had was streamlined steam passages, which caused less back pressure from steam once used.”

The locomotive also had something few classes of locomotives carried: “The A4s were all fitted with Flaman speed recorders,” says Gwynne. “The Flaman not only showed the crew how fast they were going but crucially, kept a paper record which recorded speed and location, and which could be examined back at the shed. Introducing high speed in a controlled way was clearly not left to chance by Gresley.”

A speedometer with readouts would come in handy if you were in the hunt for a speed record, and as mentioned at the beginning, Gresley was a hunter. Even though Gresley’s larger and long-term aspirations were for ever-more-efficient high-speed railway systems, Gresley was a keen competitor, well aware of the rival LMS line’s English steam record of 114mph in 1937 and of the 124.5mph of a German class 5 in 1936.

The amusing part of the historic run was that Gresley seemed more concerned with besting the times of his competitor’s West Coast LMS line, rather than hitting the record books. He was quoted as saying to his Senior Carriage Assistant, “Do you think we can beat LMS?” and when told yes, said, “Will you fix it for next Sunday?”

In the summer of 1938, Westinghouse had developed a more effective variant of the vacuum brake, called the Quick Service Application brake. What better way to test braking than by pulling out all the stops on a steaming train?

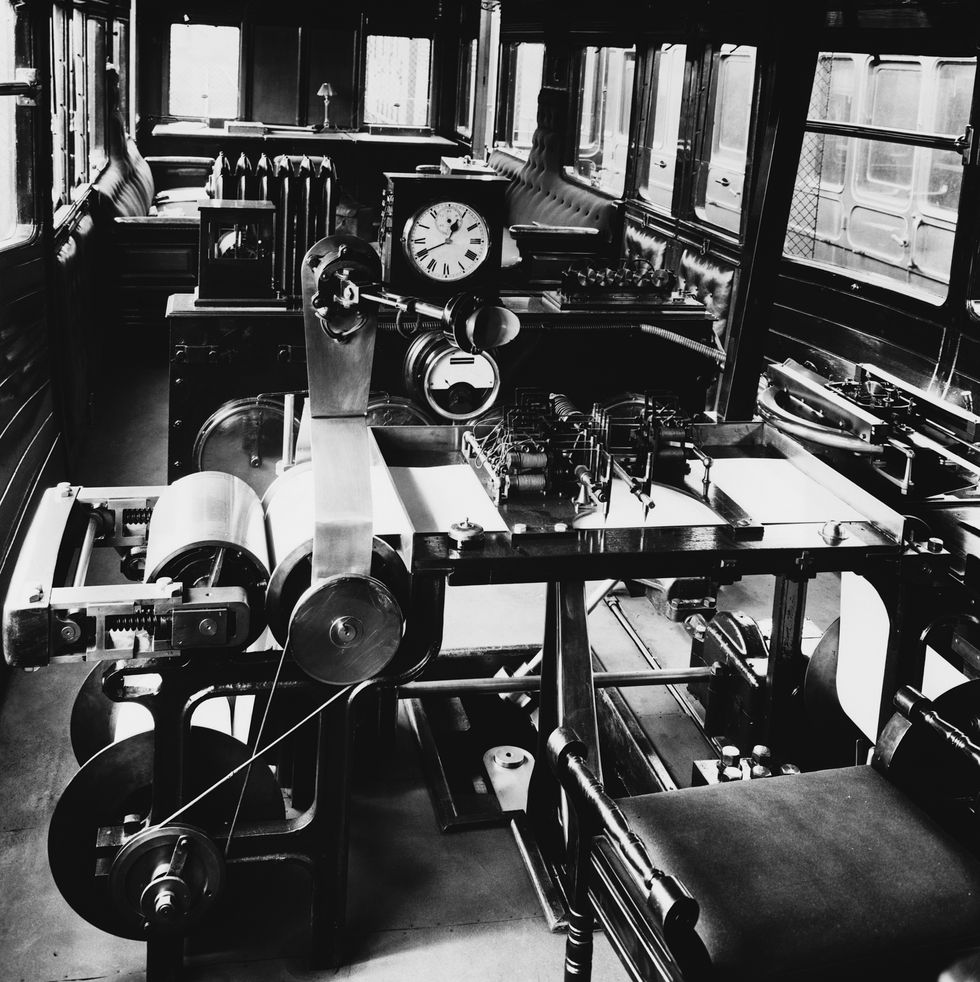

And to be doubly sure that the speed books weren’t cooked, Gresley ordered that a dynamometer car, with its large electric speedometer suspended from the ceiling, be added to the train, along with three twinset railcars.

A Steam Record for the Ages

All the elements were in place, except the human element.

Gresley turned to Joe Duddington, an engineer with 27 years on the footplate, paired with Fireman Tommy Bray. Duddington was known as a driver capable of piloting a steam train at sustained speed. Well-armed in that regard, the Mallard set off on that fateful July Sunday with additional crew (though not Gresley himself), various LNER staffers, a dynamometer car technical crew, and a team of Westinghouse employees. Because of their speed, the A4s were dubbed “streaks” by rail enthusiasts, and so the “Blue Streak” Mallard—with its provocative Bugatti-inspired Garter Blue paint job—was ready for its record-breaking run.

Late in the afternoon, at Stoke Bank on the main line between Grantham and Peterborough—with the firebox burning a ton of coal and the engine’s middle cylinder overheating—the Mallard reached a steady 125 mph and touched briefly on 126 mph, according to dynamometer verification later that day.

What Is a Dynamometer Car?

At first glance from the outside, the Mallard’s Dynamometer car looks like a standard passenger car of the era, with its polished wooden sides and its many windows. But inside is a different story. There is a large central desk, surrounded by many types of instrumentation housed in brass cases. The desk’s center holds a large paper roll which recorded the locomotive's moment-by-moment performance, information which was incoming from a specially outfitted axle on the car, which measured things like torque, dynamic horsepower, and rotational speed from the wheels.

The scrolling paper was time-indexed so the train’s performance could be recorded in repeated, short-increment regular intervals. The operating principle of the Dynamometer car is based on the basic equation for power being equal to force times distance over time. The Mallard had the power and the force, and its record has held for nearly a century.

But it wasn’t an easy trip, according to the National Railway Museum’s website:

“It was claimed the train rocked so violently that dining car crockery smashed, and red-hot, bullet-like cinders from the locomotive broke windows at Little Bytham...The force exerted by the brakes being applied caused Mallard’s big end bearing to run hot, and a slow run to Peterborough was needed to prevent Mallard from being written off.”

Beth Furness, the Rail Delivery Coordinator for the National Railway Museum, has been involved with steam engines as a volunteer—from Cleaner to Fireman to Driver—for 27 years, and knows what it’s like to be behind the controls of the powerful Mallard.

“The best thing to do with an engine built for such speed is to take your time with the controls,” she says. “The wide firebox can be very hot to work with if you are not used to them—it is one of the few engines I will wear gloves when firing. Once you set off, you can relax into the beat that the locomotive gets into.”

The Mallard Moves Through Time

The Mallard—in all of its 70 foot, 165-ton splendor—was a mere four months old when it made its historic run. All the 4-6-2 wheel-system A4s were designed for 100 mph+, and the A4 Pacifics racked up some serious passenger comfort mileage on Britain’s mainlines. The express trains from London to Edinburgh were particularly popular and productive.

The Mallard would cover more than 1.5 million miles before it was retired in 1963 along with many of the other A4s in the 1960s. The more efficient and less labor-intensive diesel-electrics were already getting some use in the rail world in the 30s, specifically on trains like the German Fliegende Hamburger and the American Burlington Zephyr. They gained broader use in the 40s and moved to prominence in the 50s and beyond. The last passenger steam train in the U.K. was decommissioned in 1968. The A4s would be some of the last steam engines in regular public service.

While some A4s would go on to languish in obscurity, this would not be the fate of the magnificent Mallard. In 1975, the locomotive became a member in high standing at the National Railway Museum in York, U.K. In the 1980s, the museum had a team of steamfitters restore the engine, and the locomotive hauled some special commemorative, short-run trains in the later 80s.

“Back then the loco was complete, so the work would have been to check all the moving parts,” says Gwynne. “The boiler would have had a partial retube and I believe the firebox gave concern. Regulations have changed, so any return to steam now would be much more complicated and would involve extensive boiler repairs, with the boiler out of the frames,” he says.

Since the 1980s, the locomotive has been out on the rails for a number of commemorative occasions since its retirement. On July 3, 2013, the 75th anniversary of the breaking of the speed record, all six of the surviving A4s were exhibited in the Great Hall of the National Railway Museum, including the 4496 Dwight. D. Eisenhower, brought over from the U.S. for the occasion, and the 4489 Dominion from Canada.

And before the big anniversary party, the Mallard needed to look the part, and received a totally restored paint job—complete with its iconic black-and-blue color palette.

Today, the Mallard enjoys a prominent perch at the museum. A simulator immerses visitors into the sights and sounds of the 1938 record run. The locomotive itself draws more than 800,000 visitors a year.

“It is clear that everyone loves Mallard; there are always people taking photographs of it, or taking selfies with themselves in front of Mallard,” says Gwynne. “It remains the case that Mallard’s claim as the ‘fastest steam locomotive in the world’ is a source of national pride.”

In July 2019, it appeared for the first time in 30 years at York station—along with the famed Flying Scotsman locomotive—to salute the inauguration of LNER’s new Azuma passenger train. Among its runs, the Azuma will cover the London to Edinburgh route, so well served by the steam locomotives of times past.

Modeled on the Japanese bullet trains, the Azuma is loaded with fuel- and noise-conservation benefits unknown in the steam era. And since the Mallard was acclaimed for speed, it should be mentioned that the Azuma will run at speeds up to 125mph, something the Mallard knows a thing or two about.

But despite being technology of another era, the Mallard still lights the fireboxes of our collective imagination.

“With a steam engine you have a very good sense what is going on with the steam,” Furness says. “You become part of the engine...there is nothing in the world that compares to working an engine at full cry. It is definitely something that stirs the soul.”

Tom Bentley is still trying to figure out what flavor of writer he is, but so far he’s a short story writer, novelist, essayist, travel writer, journalist, and business copywriter. He edits all that stuff too. His singing has been known to frighten the horses. See his lurid website confessions and blog at www.tombentley.com.