1895 LINOTYPE MODEL 1

By the mid-19th century, the printing industry had seen the advancement of technology in almost all aspects of the trade except that of typesetting; type was still tediously set and distributed by hand, the same as it was done since the days of Gutenberg. The race was on to invent the machine that would solve this problem. Many entered this race with little success, including well-known figures like Mark Twain, who invested his fortunes in the ill-fated Paige Compositor. The honors went to a young German immigrant, Ottmar Mergenthaler, who in 1886 gave the world the Linotype machine, one of the greatest inventions since Gutenberg’s perfection of moveable metal type.

The process of invention is rarely the result of pure inspiration, but rather a progression of ideas, innovations and experiments that eventually culminate in a new invention or an advancement of a technology. It took Mergenthaler ten years of experimentation with various ideas to finally arrive at the Linotype in 1886. As a young boy in Germany, he had “very successfully handled the rather rebellious vintage clock,” which led Mergenthaler to accept an apprenticeship as a watchmaker; he remained as such until his immigration to America at the age of 18 in 1872. The skills he had acquired working with clocks helped the young Mergenthaler to secure a position in the shop of an instrument maker in Washington, D.C., the city that was the center for all the great inventors and inventions of world at that time. It was in this environment that the inventive talents of Mergenthaler were nurtured and developed.

The shop Mergenthaler was associated with moved to Baltimore, and it was there, in August of 1876, that he was approached about the invention of a machine that would “produce by type-writing a print just like that produced from printer’s type.” The machine, finished in the summer of 1877, was a typewriter transfer machine for use in the lithography process. The machine itself functioned accurately and rapidly, but the problems occurred in attempting to transfer the image to the lithographic stone for printing. Apparently, more energy was spent in developing the machine rather than in researching the requirements for lithography, which were more exacting than anticipated. The machine had very limited success and was eventually abandoned in favor of another approach and another process besides lithography.

Mergenthaler’s next attempt was in the area of stereotyping, or “the construction of a writing machine which would impress its characters into papier-maché and produce type from these matrices by the stereotypic process.” The machine was completed by the latter part of 1878 but again, Mergenthaler encountered severe difficulties, this time in the process of stereotyping; the molten metal for casting would cool before filling the mould that contained the matrices. This problem compounded with others, resulting in Mergenthaler’s subsequent abandonment of this machine as well.

In 1884, Mergenthaler attacked the problem again, but this time from a different angle. The machine he invented was a type casting machine with brass bars bearing indented characters, known as the Band Machine. The machine was very satisfactory, but the matrix bands were not true enough and the operator was unable to see the result of his work until the process was completed, making corrections costly and time consuming. Mergenthaler concluded that only a machine that conformed closely to the methods of hand composition would succeed in overcoming the prejudices of the printing trade. He now devoted his time to developing a machine that would cast type from single matrices rather than using the bands, and one that allowed the operator greater control over the results. The machine he developed was the Blower Linotype of 1886, the direct predecessor of the Linotype that became the staple of the printing industry for the next eighty years.

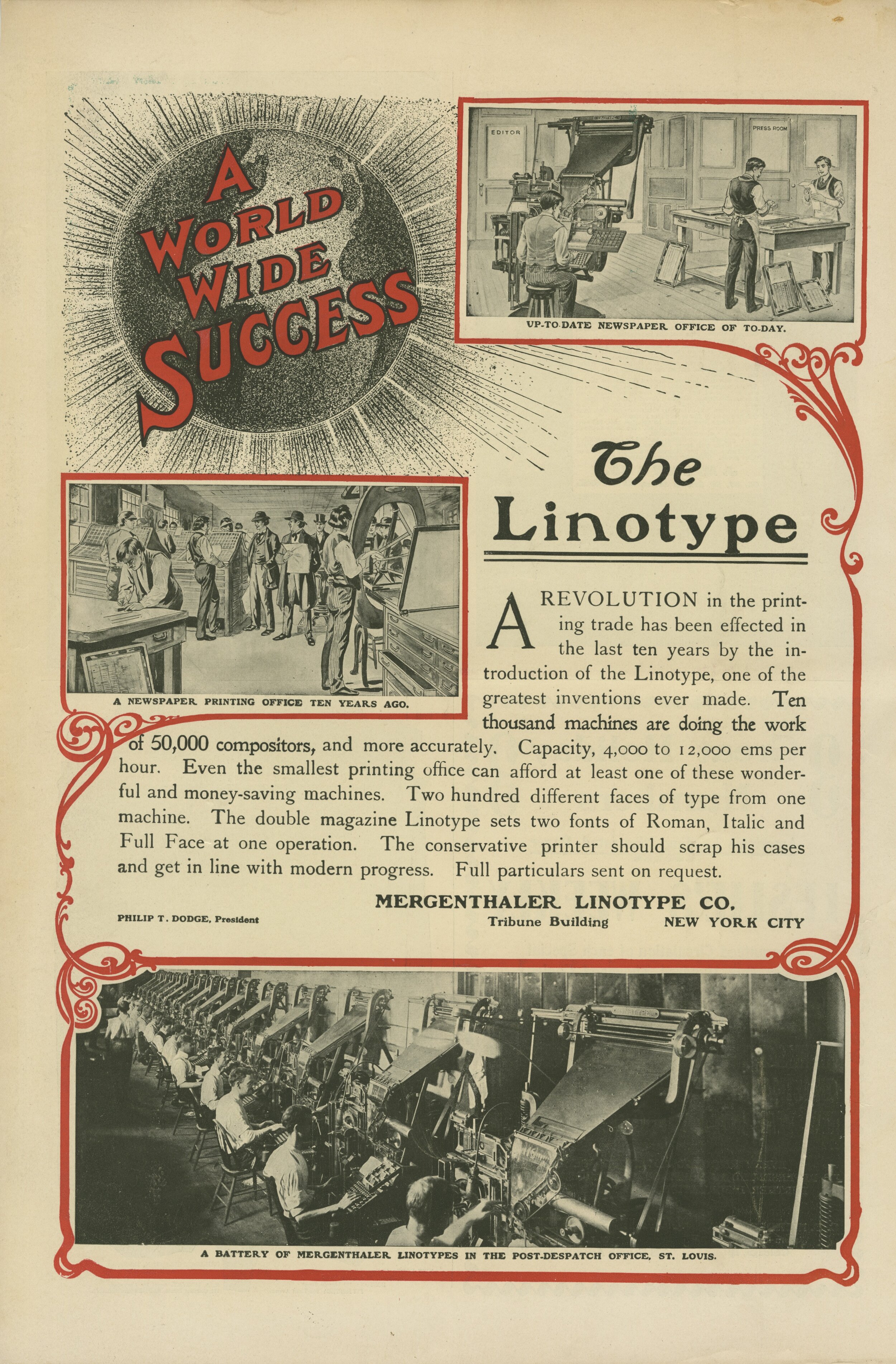

In July of 1886, the first of these machines was completed and placed in the composing room of the New York Tribune. It was used to help compose both the daily paper and the first book “printed without type, being the first product in book form of the Mergenthaler Machine which wholly supersedes the use of movable type” (from the colophon of book). The Book, The Tribune of Open-Air Sports, is now a much sought-after collector’s item. The use of the machine in production at the Tribune on these products exposed some of the weak points in the machine, leading Mergenthaler to introduce the improved Linotype Model 1 in 1890, which is the machine that revolutionized the world and became the standard for machine composition until the late 1960’s.

Mergenthaler was a man endlessly devoted to the perfection of his machines, as seen in the persistency he exercised in attempting to solve the typesetting dilemma. His invention was described by Thomas Edison as the “eighth wonder of the world.” The museum has several Linotypes in working order. Visitors can see them in operation every Saturday.