Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Flora of Seychelles

Uploaded by

Sanka78Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Flora of Seychelles

Uploaded by

Sanka78Copyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/237309806

Virtual gallery of the vegetation and flora of the

Seychelles

Article in Bulletin of the Geobotanical Institute ETH · January 2003

CITATIONS READS

11 473

5 authors, including:

Karl Fleischmann Christoph Kueffer

ETH Zurich Hochschule für Technik Rapperswil

11 PUBLICATIONS 252 CITATIONS 186 PUBLICATIONS 4,390 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Peter J. Edwards

ETH Zurich

312 PUBLICATIONS 13,560 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Agroforestry View project

Increased competitive abilities in introduced species View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Christoph Kueffer on 21 May 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

K. FLEISCHMANN ET AL .

RESEARCH NOTE

Virtual gallery of the vegetation and flora of the Seychellles

KARL FLEISCHMANN*, PAULINE HÉRITIER, CYRILL MEUWLY,

CHRISTOPH KÜFFER & PETER J. EDWARDS

Geobotanical Institute, ETH Zürich, Zürichbergstrase 38, CH-8044 Zürich, Switzerland;

* corresponding author: fleischmann@geobot.umnw.ethz.ch

Summary

1 The Seychelles archipelago has been identified as a biodiversity hotspot by interna-

tional conservation agencies. One of the major threats to the Seychelles native species

and forests is the rampant spread of a large number of invasive alien plant species. As a

basis and reference for conservation measures, the native flora and some vegetation

types of granite islands of the Seychelles are briefly described and illustrated with photo-

graphs.

2 The original flora of the granite islands was rather poor with approximately 250 spe-

cies of indigenous flowering plants of which about 34% (84 taxa) are supposed to be or

to have been endemic to the Seychelles. About 80 fern species grow on the islands,

several of which are considered endemic.

3 The main natural vegetation types are: coastal plateau, lowland and coastal forests,

mangrove forest, riverine forest, intermediate forest, mountain mist forest, glacis type

vegetation (inselbergs)

4 A collection of photographs of plant species and vegetation types from the Seychelles

(‘virtual gallery’ can be viewed or downloaded at www.geobot.umnw.ethz.ch/publica-

tions/periodicals/bulletin.html

Keywords: conservation, endemism, island flora, plant invasion, Seychelles, vegetation

types.

Nomenclature: Friedmann (1994).

Bulletin of the Geobotanical Institute ETH (2003), 69, 57–64

Introduction

The Seychelles archipelago consists of about fore had an extremely long time to develop

a hundred granite and coralline islands near independently from that of the rest of the

the equator in the Western Indian Ocean world, mainly through natural evolutionary

(Fleischmann et al. 1996). These islands prob- processes, leading to a high level of ende-

ably split from Gondwana some 65 million mism. The unique status of the granite islands

years ago and have been isolated from conti- of the Seychelles as oceanic islands of conti-

nents ever since. The Seychelles flora there- nental origin, and the phytogeographical im-

Bulletin of the Geobotanical Institute ETH, 69, 57–64 57

VIRTUAL GALLERY OF THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THE SEYCHELLLES

portance of the islands as combining African, • Propagules dispersed by animals. Animal-

Madagascan and Indo-Malaysian elements in dispersed seeds are typically fleshy berries,

their flora make it a region of great floristic relatively small in size, and variously colo-

interest. The fact that at the time of the first red. The dispersers of greatest importance

human settlement on Mahé in the 1770’s the in the Seychelles are fruit-eating birds and

flora had evolved continuously and without bats. Prominent amongst introduced spe-

human interaction for many millions of years, cies with bird-dispersed fruits are Cinnamo-

certainly adds to the outstanding status of the mum verum, Psidium cattleianum and Clide-

Seychelles’ island vegetation. In fact the Sey- mia hirta. Species using animals or wind as

chelles have been identified as a biodiversity dispersal mechanisms (i.e. Paraserianthes f.)

hotspot by Conservation International and as are capable of quickly invading native eco-

a centre of plant diversity by the WWF and systems in areas remote from where the

IUCN. adults themselves are planted. As for Cin-

One of the major threats to the native spe- namomum v. and Psidium c. an additional

cies and forests of the Seychelles is the ram- attribute making these plants even worse is

pant spread of a number of alien plant spe- that they can reproduce vegetatively as well

cies across the islands (Fleischmann 1997); as by seeds.

the most invasive ones are Cinnamomum • High fecundity. Species that produce many

verum, Psidium cattleianum, Clidemia hirta, seeds per plant each year can invade new

Merremia peltata and Paraserianthes falca- habitat patches more rapidly than can most

taria. These plants displace the distinctive native plants that produce relatively few

native flora of the Seychelles, resulting in the seeds (Peters 2001). For example, Cinna-

loss of diverse native forests. The situation in momum v. and Clidemia h. (the latter is now

the Seychelles is particularly serious because the subject of a control effort by state and

there are several rare, endemic species like private organizations) produce large num-

Medusagyne oppositifolia, Secamone schimpe- bers of seeds, so that their populations can

riana, Vateriopsis seychellarum etc. which are increase very rapidly, which partially ac-

fated to extinction following the invasion of a counts for the great threat they pose to the

great variety of introduced organisms. It is Seychelles’ forests.

generally accepted that invasive alien species • Fast growth: Fast-growing plants that

may have a competitive or reproductive ad- quickly reach maturity will be more inva-

vantage over native species (Parendes 2000). sive and harder to control than slower-

Besides this, the introduction of certain plant growing plants. An outstanding example

species may promote further change be- of the importance of this phenomenon is

cause they affect ecosystem processes. Inva- Clidemia h. which was first seen on Mahé

sive species can influence nitrogen availabil- island in 1993 (Gerlach 1993). Since then

ity by changing litter quantity and quality, single plants have been found all over the

rates of N2-fixation, or rates of nitrogen loss island. By competing with native species

(Evans et al. 2001; Anderegg & Wiederkehr in gaps, Clidemia h. invasion has the po-

2001). A variety of biological attributes of tential to alter forest regeneration (Peters

plants serve to make them invasive, but in 2001).

the Seychelles three are of primary impor- In order to prevent fundamental changes to

tance. the indigenous and endemic vegetation of the

58 Bulletin of the Geobotanical Institute ETH, 69, 57–64

K. FLEISCHMANN ET AL .

Seychelles an ongoing commitment to con- to carefully describe and document their

trolling invasive alien species is required. This present condition as a reference for future

commitment is based on scientific research conservation measures. The purpose of this

which provides a wider perspective on the article is (a) to give a brief account of the his-

problem of invasion by alien species, and a toric development of the Seychelles flora and

rational basis for habitat management (i.e. the (b) to describe its main vegetation types with

control of this invasion). It has become obvi- characteristic plant species. This description

ous that the protection of land in itself will not is illustrated by photographs available in elec-

be sufficient to save the habitats. Since most tronic form. A similar account was given by

areas of the Seychelles are heavily infested Francis Friedmann (1987) in his book “Flow-

with alien plants, the crucial question is: what ers and Trees of the Seychelles”. This book

can be done to save the remaining, intact na- comprises a selection of remarkable pictures

tive forests? To address this question, several of the Seychelles flora on the granite islands,

research projects in the field of conservation including typical habitats and beautiful sce-

and invasion biology have been conducted nes. Unfortunately, this work is now out of

through the Geobotanical Institute in Zürich print and cannot be re-printed in the original

over the last eleven years. form because many of the original pictures

Despite the wide scale destruction of the were destroyed by fire. Therefore, this contri-

original island vegetation, there are sites bution and the associated “virtual gallery”

where at least some of the original elements of with photographs of prominent plants and

the natural flora have been preserved. On typical vegetation types is intended to be a

Mahé and Silhouette there are still substantial small substitute of what is no longer available.

areas of humid high-altitude forests and

inselbergs containing a rich endemic flora.

Luckily, relatively few of the endemic plant The Seychelles flora and its history

species are so far known to have become ex- Thanks to a large number of contributors and

tinct on all islands (Carlstroem 1996). How- the rather restricted area of the land, the flora

ever, the fact that populations of many en- of the Seychelles is at present rather well

demic and threatened species are extremely known and we have a fairly good knowledge

small is a serious concern. For many of these of the conservation status of most species.

species, especially those of the ancient forests The original flora of the granite islands was

at intermediate altitude, the situation is critical rather poor with approximately 250 species

since their natural habitats no longer exist. of indigenous flowering plants of which about

These species (e.g. Medusagyne oppositifolia ) 34% (84 taxa) are supposed to have been en-

will never survive without human interfer- demic. There are also about 80 fern species

ence. It is most likely that the displacement of growing on the islands, several of which are

the native flora through competition with in- supposed to be endemic to the Seychelles

vasive exotic taxa will reduce biodiversity (Fleischmann 1997).

through the altering of the physical environ- While most oceanic islands have received

ment, increased erosion and perhaps the dis- their flora predominantly by long-distance

ruptive effects on nutrient recycling. (i.e. 1000 km) dispersal, the native flora of the

Given the critical status of the last remnants Seychelles probably derived predominantly

of native Seychelles vegetation, it is essential from ancestors which were already present

Bulletin of the Geobotanical Institute ETH, 69, 57–64 59

VIRTUAL GALLERY OF THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THE SEYCHELLLES

on the Seychelles microcontinent 65 million varieties), and in the Hypoxidiaceae (Hypoxi-

years ago when the archipelago was about to dia rhizophylla, Hypoxidia mahensis) (Carl-

split up from Gondwanaland. Few species in stroem 1996).

the Seychelles have seeds that are adapted to The present flora of the Seychelles is rela-

long-distance dispersal. Before the arrival of tively homogeneous (Carlstroem 1996). No

humans, only a minor part of the native flora, differences in morphological characters were

mainly in the coastal zone and in the wet- observed between populations on different is-

lands, had probably arrived by long-distance land (Fleischmann, personal observation).

dispersal. However, it is still possible that genetic differ-

As can be expected from the geological his- entiation exists among the different island

tory of the area, the native flora of the Sey- populations; this could be revealed by genetic

chelles includes elements of African, Mada- analyses.

gascan and Indo-Malaysian origin, with the

latter being the most prominent (Cox & Moor

1996). A considerable proportion of the en- Natural vegetation types on the granite

demic species are probably relict elements islands

from an ancient widespread Gondwana-flora Although a full documentation of the original

which became extinct on the mainlands but vegetation types of Seychelles is lacking,

survived in the Seychelles. Many primitive some conclusions can be drawn from the

characters have been preserved in relict spe- present vegetation, in combination with old

cies such as Medusagyne oppositifolia and written records. The following vegetation

Psathura seychellarum (Procter 1974). types have been identified on the granite is-

After the ice age a period of submergence lands.

followed when the Seychelles microcontinent

was reduced from a more or less continuous COASTAL PLATEAU

land mass of 43’000 km2 to scattered islands We only have very scarce reports on the com-

2

with a total area of about 245 km (Stoddart position of the shore vegetation from the ear-

1984). This dramatic reduction in land area lier records, which mainly noted the more

undoubtedly must have been accompanied important timber trees. The exploitation of

by massive extinctions in the flora. The spe- the trees of the beach crest as well as the con-

cies occurring in the lowlands would have struction of sea walls, land reclamation, con-

been especially affected. This theory is sup- struction of houses, coconut plantations, etc.

ported by the fact that the main part of the have all contributed to the alteration of the

endemic species are found at intermediate original coastal vegetation. Our knowledge

and high altitudes, whereas only two species about the original composition is therefore

are confined to the coastal zone. limited (Sauer 1967).

During the long period of isolation of the By the time the first settlers arrived on the

islands, evolution may have slowly given rise Seychelles the shores were fringed with coco-

to new plant species like Lodoicea maldivica nut palms which were believed to have grown

(Edwards et al. 2002). Groups of taxa which from nuts cast up by the sea. Other trees men-

have probably evolved after the isolation of tioned from the shores in the earlier reports

the Seychelles microcontinent exist within were Casuarina equisetifolia, Terminalia catap-

genera like Gastonia (three species and three pa, Calophyllum inophyllum, Cordia subcor-

60 Bulletin of the Geobotanical Institute ETH, 69, 57–64

K. FLEISCHMANN ET AL .

data. It has been much discussed whether was described as being the same but smaller.

Terminalia catappa, Casuarina equisetifolia and The islands of Cousin, Cousine and Aride

Cocos nucifera were brought to the Seychelles were apparently never well wooded and were

by the first people visiting the islands or described as covered by scrubland even in the

whether they were present before the first ar- first records from Malavoise 1786–87 (Carl-

rival of humans. Certainly they were already stroem 1996).

widely spread by this time, and they now The primary lowland flora was apparently

form an integral part of the coastal vegetation. composed partly of endemic species as well

The dominant shrub on the beach crests as indigenous species more widely spread on

today is Scaevola sericea. Other common most islands in the Indian Ocean; however, it

shore-line trees are Cocos nucifera, Calo- is obvious that the endemic species played a

phyllum inophyllum, Hernandia nymphaeifo- less important role in the lowland vegetation

lia, Hibiscus tiliaceus, Barringtonia asiatica, than at the higher elevations.

Guettarda speciosa and Cordia subcordata, in

the past frequently mixed with Tournefortia M ANGROVE FOREST

argentea, Suriana maritima and Sophora to- Near the sea level were also the mangrove

mentosa. Scramblers and creeping plants are swamps dominated by the same six species of

common in the shore vegetation. Most spe- mangrove trees that occur today, with Avi-

cies growing along the coast are species com- cennia marina and Rhizophora mucronata be-

mon to the shores of most tropical islands and ing the most prominent at present. The ex-

the endemic flora has never played an impor- posed open sea coasts have never been colo-

tant role on the littoral. nised by mangroves. Hence the mangrove

have always been found only on the more

LOWLAND AND COASTAL FORESTS tranquil lagoon shores. The earliest settlers

The lowland forests originally covered the reported extensive areas covered with almost

mountain sides up to about 200–300 m. The impenetrable mangroves, especially along the

coastal plains were originally described as be- East coast of Mahé. All species known from

ing covered by magnificent trees reaching up the mangrove swamps have a wide distribu-

to 20–25 m, with a circumference of 4–5 m tion and no endemic species are known to

and with very straight trunks. The trees were occur in this vegetation type.

spaced at 2.5–3.5 m from each other with

hardly any branches for the first 15–20 m. RIVERINE FOREST

Species like Terminalia catappa, Casuarina equi- The vegetation along most rivers in the Sey-

setifolia, Intsia bijuga, Calophyllum inophyllum, chelles was much affected by human activities

Heritiera littoralis, Mimusops seychellarum, and there is little information on riverine for-

Vateriopsis seychellarum, Syzygium wrightii and ests to be found in the literature. Most of the

Cordia subcordata were described as common remaining river forests are composed of palm

in this zone in the first records. Palm trees, trees, especially Phoenicophorium borsigianum,

especially Phoenicophorium borsigianum, Ne- Verschaffeltia splendida, frequently associated

phrosperma vanhoutteana and Deckenia nobilis with Barringtonia racemosa and Pandanus bal-

were also mentioned from the original low- fouri at the lower altitudes. Possibly Vateriopsis

land forests, especially on dry ridges. The spe- seychellarum also formed part of this commu-

cies composition of the woods of Silhouette nity. There also seems to be a constant asso-

Bulletin of the Geobotanical Institute ETH, 69, 57–64 61

VIRTUAL GALLERY OF THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THE SEYCHELLLES

ciation of Pandanus hornei and Verschaffeltia tonia crassa (Bwa Bannann). Palms were of

splendida. only minor importance in the forests of the

more humid type. There were also large

I NTERMEDIATE FOREST stands of screwpines (Pandanaceae). Tree

From 200 to 500 m there was an intermediate ferns (Cyathea seychellarum ) have been de-

forest zone. These forests were rich in species scribed as a common feature in the humid in-

and had a high canopy at least occasionally termediate forests and along the river ravines.

reaching up to 30–40 m. The big trees were Much of the dry ridges with a shallow soil

spaced at approximately 9–10-m intervals, have been described as having a Mimusops /

and the trunks were very straight. The forest Excoecaria dominated forest type. This kind

at intermediate altitudes was the one richest of vegetation is now only to be found as scat-

in endemic species; endemics made up the tered remnants on rocky outcrops. The cree-

main part of the vegetation. These forests per Merremia peltata and the only recently es-

have now been almost entirely cut down and tablished Clidemia hirta have started to heav-

most of the remaining areas have been heavily ily invade the lowland- and intermediate for-

invaded by exotic species or have been ests on Mahé.

planted with exotic forest trees. Areas with

intermediate forests with at least remnants of M OUNTAIN MIST FOREST

the high canopy are now very rare in the Sey- High altitude forest originally covered most

chelles. Most of the remaining forests have land above 400–500 m in the Seychelles. On

been combed through for timber and most mainland tropical mountains, mist forest is

suitable tall trees have been cut down. It is typically found at altitudes of between 2000

therefore difficult to judge what the species and 3500 m, but on steep small islands like

composition in these forests was like and evi- the Seychelles mist forests develop at much

dence of its former appearance can only be lower altitudes. The transition into the mist

gained from much modified scattered forest zone is gradual and depends greatly on

patches. Our best knowledge of the vegeta- local conditions. In many places the transition

tion from the intermediate altitudes comes between the intermediate and high altitude

from the exposed rocky areas and some river forests have been obscured by the dominance

ravines which have served as sanctuaries for of exotic vegetation, which grows from sea

much of the flora. level to the highest elevations, making the

At drier sites the intermediate forests have transition less obvious. The conditions at the

probably been dominated by the endemic high altitudes are more humid and a moun-

palm trees associated with Campnosperma tain mist forest develops where the annual

seychellarum, Diospyros seychellarum, Meme- rainfall is well over 3000 cm yr-1. These areas

cylon eleagni, Excoecaria benthamiana, Para- are often enshrouded in low clouds.

genipa wrightii, Erythroxylon seychellarum, Even these high altitude areas have suffered

Syzygium wrightii, Canthium bibracteatum, from heavy cutting of selected trees, so there

Soulamea terminalioides, etc., whereas forests are only a few relict stands of primeval forest

at more humid sites were dominated by left. The remaining areas, however, give us an

Northea hornei, Dillenia ferruginea, Vateriopsis idea of its former appearance. The remnants

seychellarum, Grisollea thomassetii, Pouteria of high altitude forest are still dominated by

obovata, Campnosperma seychellarum, and Gas- native species, giving an idea of the original

62 Bulletin of the Geobotanical Institute ETH, 69, 57–64

K. FLEISCHMANN ET AL .

structure of this forest type. The mountain seashore to the mountain tops. Extreme

mist forest is rich in mosses, lichens, filmy edaphic and climatic conditions (high degree

ferns and epiphytic orchids. Tree ferns (Cya- of insolation combined with high evaporation

thea seychellarum) are a common feature of rates) exert an strong selective pressure re-

this forest type. Climbers like Schefflera sulting in a vegetation that is very different

procumbens were described as a characteristic from the surroundings. Soil which accumu-

feature in the past but are now much less lates in pockets and fissures of the rock con-

common. The trees in the mist forest exhibit a sists largely of coarse quartz sand with vari-

reduced tree stature and increased stem den- able amounts of peaty organic matter. If the

sity compared to forests of lower lying areas. peat cover is destroyed by clearing of the veg-

As a result of the cutting of the best timber etation or fire the underlying bare rock is ex-

trees in the canopy, the second-story trees of- posed. These factors have given rise to a veg-

ten form a new lower canopy today which is etation type which is characterised by an out-

lower than the original. However, big trees standing degree of endemism, locally as high

can still be found at undisturbed sites at as 96 %. Taxa typically growing on inselbergs

higher altitudes indicating that the canopy are Pandanus multispicatus, Memecylon elea-

was previously up to about 15 m tall with a gni, Mimusops seychellarum, Excoecaria ben-

circumference of more than 2 m. Northea hor- thamiana, Soulamea terminalioides and on

nei was, and still is, the dominant species of just a few locations the very rare Medusagyne

the canopy of this zone. It commonly occurs oppositifolia.

with Pandanus seychellarum and with a sec-

ond-story vegetation of Roscheria melano-

chaetes, Gastonia crassa, Psychiotria pervillei, Virtual gallery

etc. In the original forest at the higher alti- A collection of photographs of typical vegeta-

tudes endemic species dominated the vegeta- tion types and their characteristic plant spe-

tion. The total number of endemic species in cies is given under http://www.geobot.umnw.

the mist forest is, however, lower than at the ethz.ch/publications/periodicals/bulletin.html

intermediate altitudes. (on this web page, select “Electronic Appen-

dices”, and there “App. 2003-7”).

GLACIS TYPE VEGETATION (INSELBERGS) This Appendix consists of a text part, which

On the granite islands of the Seychelles there provides a concise compendium of the most

is a vegetation element which cannot be re- important vegetation types, and a total of 74

lated to altitude. This vegetation type, com- photographs, which can be accessed from the

prising vegetation growing on solitary, often text through hyperlinks. Most plant species

monolithic rocks or parts of mountain sys- mentioned in the two preceding sections of

tems which rise abruptly from their surround- this article are represented in the virtual gal-

ings, is locally called “glacis-type” vegetation. lery. The photographs can be viewed on the

The term “glacis” is French and means screen and downloaded as jpg files. They

“steep, rocky slope”. Glacis are freely ex- have been produced by Karl Fleischmann,

posed precambrian rock outcrops, which in Pauline Héritier and Cyrill Meuwly during

geomorphological terms are known as insel- field work in 2001–2002. They can be used

bergs. On the Seychelles they occur through- freely for teaching and scientific purposes,

out the above-mentioned habitats from the provided that the full source is indicated.

Bulletin of the Geobotanical Institute ETH, 69, 57–64 63

VIRTUAL GALLERY OF THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THE SEYCHELLLES

It is the authors’ hope that a wider apprecia- Peters, H.A. (2001) Clidemia hirta invasion at the

tion of the beauty and uniqueness of the Sey- Pasoh Forest Reserve: An unexpected plant in-

vasion in an undisturbed tropical forest. Bio-

chelles flora, as reflected by the photographs

tropica, 33, 60–68.

in the virtual gallery, will stimulate further Parendes, L.A. & Jones, J.A. (2000) Role of light

research aimed at protecting these plants availability and dispersal in exotic plant invasion

against increasing human disturbance and al- along roads and streams in the H. J. Andrews

ien plant invasions. Experimental Forest, Oregon. Conservation Biol-

ogy, 14, 64–75.

Procter, J. (1974) The endemic flowering plants of

the Seychelles: an annotated list. Candollea, 29,

Acknowledgements 345–387.

Robertson, S.A. (1989) Flowering plants of Sey-

Karsten Rohweder and Hans-Heini Vogel

chelles. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

skilfully supported us in constructing the vir- Sauer, J.D. (1967) Plants and man on the Seychelles

tual gallery. We also thank Sabine Güsewell coast. A study in historical biogeography. The Uni-

and an anonymous referee for helpful com- versity of Wisconsin Press, Madison, London.

ments on the manuscript. Stoddart, D.R. (1984) Biogeography and Ecology of

the Seychelles Islands. Monographiae Biologicae,

Boston & Lancaster.

Whittaker, R.J. (1998) Island Biogeography. Oxford

References University Press, Oxford.

Anderegg, M. & Wiederkehr, F. (2001) Problems

with Paraserianthes falcataria on Mahé, Sey- Received 11 April 2003

chelles. Master’s Thesis, Geobotanical Institute Revised version accepted 1 July 2003

ETH, Zürich.

Carlstroem, A. (1996) Endemic and threatened plant

species on the granite Seychelles. Report to the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Division of Environ-

ment, Seychelles.

Cox, C.B. & Moor, P.D. (1996) Biogegography, an

ecological and evolutionary approach. Blackwell

Science, Oxford.

Edward, P.J., Kollmann, J. & Fleischmann, K.

(2002) Life history evolution in Lodoicea maldi-

vica. Nordic Journal of Botany, 22, 227–237.

Evans, R.D., Rimer, R. & Sperry, L. (2001) Exotic

plant invasions. Ecological Applications, 11, 1301–

1310. Electronic Appendix

Fleischmann, K., Porembski, S., Biedinger, N. &

Barthlott, W. (1996) Inselbergs in the sea: Vegeta- Appendix 1. Typical vegetation types of the

tion of granite outcrops on the islands of Mahé,

Praslin and Silhouette (Seychelles). Bulletin of the Seychelles (classified according to altitude)

Geobotanical Institute ETH, 62, 61–74. and their characteristic plant species, with

Fleischmann, K. (1997) Invasion of alien woody hyperlinks to colour photographs.

plants on the islands of Mahé and Silhouette,

Seychelles. Journal of Vegetation Science, 8, 5–12. The Appendix can be downloaded at

Friedmann, F. (1987) Flowers and trees of Seychelles.

ORSTOM, Paris.

http://www.geobot.umnw.ethz.ch/publica-

Gerlach, J. (1993) Invasive Melastomataceae in tions/periodicals/bulletin.html

Seychelles. Phelsuma, 1, 18–38. (select ‘Electronic Appendices’, App. 2003–7).

64 Bulletin of the Geobotanical Institute ETH, 69, 57–64

View publication stats

You might also like

- Thesis Doctor of Philosophy Komoot Abphirada 2021 Part 2Document316 pagesThesis Doctor of Philosophy Komoot Abphirada 2021 Part 2Ignat PulyaNo ratings yet

- The New Flora of The Volcanic Island of KrakatauDocument103 pagesThe New Flora of The Volcanic Island of KrakataumolineauNo ratings yet

- Objectifying The Occult Studying An Islamic Talismanic Shirt As An Embodied ObjectDocument22 pagesObjectifying The Occult Studying An Islamic Talismanic Shirt As An Embodied ObjectPriya SeshadriNo ratings yet

- 2017 Wassce Gka - Paper 2 SolutionDocument5 pages2017 Wassce Gka - Paper 2 SolutionKwabena AgyepongNo ratings yet

- From Commerce To Conquest The Dynamics of British Mercantile Imperialismin Eighteenth Century Bengal and The Foundation of The British Indian EmpireDocument20 pagesFrom Commerce To Conquest The Dynamics of British Mercantile Imperialismin Eighteenth Century Bengal and The Foundation of The British Indian Empiresnigdha mehraNo ratings yet

- Abou-El-Haj, R. A. (1974) - The Narcissism of Mustafa II (1695-1703) - A Psychohistorical StudyDocument18 pagesAbou-El-Haj, R. A. (1974) - The Narcissism of Mustafa II (1695-1703) - A Psychohistorical StudyAyşenurNo ratings yet

- I Finkelstein The Wilderness Narrative ADocument17 pagesI Finkelstein The Wilderness Narrative ARomano FaraonNo ratings yet

- Ka Avesta Dot OrgDocument254 pagesKa Avesta Dot OrgJakub ReichertNo ratings yet

- The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton TextilesDocument503 pagesThe Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton TextilesJaque PadovanNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Revolution v2Document19 pagesIntellectual Revolution v2Jesza Mei GanironNo ratings yet

- Voyages and Travels,: William Blackwood, Edinburgh: and T. Cadell, London. 1816Document296 pagesVoyages and Travels,: William Blackwood, Edinburgh: and T. Cadell, London. 1816Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Valley of The Kings and QueensDocument2 pagesValley of The Kings and QueensRocketeer LoveNo ratings yet

- The Genus ZantedeschiaDocument38 pagesThe Genus ZantedeschiaRosana MaisinchoNo ratings yet

- VivianbullwinkelbiographyDocument3 pagesVivianbullwinkelbiographyapi-294944528No ratings yet

- The Management of Museums in SharjahDocument15 pagesThe Management of Museums in SharjahNoha GhareebNo ratings yet

- Balanced Growth Theory With Respect To IndiaDocument18 pagesBalanced Growth Theory With Respect To Indiafae salNo ratings yet

- African Traditional Dance: Yohan & LawrenceDocument11 pagesAfrican Traditional Dance: Yohan & LawrenceYogie MandapatNo ratings yet

- The Factors That Led To ColumbusDocument5 pagesThe Factors That Led To ColumbusMikayla Sutherland100% (1)

- 1A Age of Crusades OverviewDocument81 pages1A Age of Crusades OverviewGleb petukhovNo ratings yet

- Feudal Monarchy in The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1100-1291 - John L. La MonteDocument309 pagesFeudal Monarchy in The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1100-1291 - John L. La MonteManuel PérezNo ratings yet

- The Story of The U.a.EDocument2 pagesThe Story of The U.a.Eiqbal2525No ratings yet

- 1 The British Maritime Trade and A National IdentityDocument13 pages1 The British Maritime Trade and A National Identityzahin ahmedNo ratings yet

- Slaveasteurorev2 95 3 0401Document29 pagesSlaveasteurorev2 95 3 0401Okan Murat ÖztürkNo ratings yet

- Flora and FaunaDocument39 pagesFlora and FaunaSesha GiriNo ratings yet

- Bilal History ArtsDocument28 pagesBilal History ArtsShariq AliNo ratings yet

- Jimphe 2019 - Journal of Multidisciplinary Perspectives in Higher EducationDocument145 pagesJimphe 2019 - Journal of Multidisciplinary Perspectives in Higher EducationSTAR ScholarsNo ratings yet

- Unit ThreeDocument15 pagesUnit ThreeFalmeta EliyasNo ratings yet

- Shari'a Law in Trinidad and Tobago?Document29 pagesShari'a Law in Trinidad and Tobago?caribbeanlawyearbookNo ratings yet

- Business Law - 2Document17 pagesBusiness Law - 2BARRACK OWUORNo ratings yet

- Trading Digital Financial AssetsDocument31 pagesTrading Digital Financial AssetsArmiel DwarkasingNo ratings yet

- Environment MicrobiologyDocument16 pagesEnvironment Microbiologymohamed ishaqNo ratings yet

- SOL History (Old)Document71 pagesSOL History (Old)Valorant SmurfNo ratings yet

- American Artifacts of Personal Adornment, 1680-1820 A Guide To Identification and Interpretation by Carolyn L. WhiteDocument339 pagesAmerican Artifacts of Personal Adornment, 1680-1820 A Guide To Identification and Interpretation by Carolyn L. WhiteJéssica IglésiasNo ratings yet

- Kitab I Nauras 1956 TextDocument178 pagesKitab I Nauras 1956 TextgnaaNo ratings yet

- "Anomaly": The andDocument17 pages"Anomaly": The andGudeta KebedeNo ratings yet

- Principality of Geza 970-998Document8 pagesPrincipality of Geza 970-998Jozsef MokulaNo ratings yet

- 2 Writing and CitylifeDocument17 pages2 Writing and CitylifeWARRIOR FFNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledLund MeraNo ratings yet

- The El Dorado of AgisymbaDocument16 pagesThe El Dorado of AgisymbaDAVIDNSBENNETTNo ratings yet

- Shuter's Hill Brewery, Alexandria VADocument7 pagesShuter's Hill Brewery, Alexandria VAMarkNo ratings yet

- Atossa Re EntersDocument24 pagesAtossa Re EntersMatheus Moraes MalufNo ratings yet

- 48 PDFDocument210 pages48 PDFEden TeklayNo ratings yet

- Ortaköy ŞapinuwaDocument16 pagesOrtaköy ŞapinuwaahmetakkayaNo ratings yet

- The Holy Storm' - Clerical Fascism' Through The Lens of ModernismDocument16 pagesThe Holy Storm' - Clerical Fascism' Through The Lens of ModernismSouthern FuturistNo ratings yet

- IRANUN123Document28 pagesIRANUN123Joseph Zaphenath-paneah ArcillaNo ratings yet

- PFAS Complaint 2022-09-29Document43 pagesPFAS Complaint 2022-09-29WXMINo ratings yet

- Sahel StrategyDocument9 pagesSahel StrategyvnfloreaNo ratings yet

- Soal Semster Bahasa Inggris IX TKJDocument4 pagesSoal Semster Bahasa Inggris IX TKJi made kariarthaNo ratings yet

- Module I Introduction To Travel and TourismDocument32 pagesModule I Introduction To Travel and TourismLavenderogre 24No ratings yet

- Burn - Lyric Age of Greece (1978, Hodder & Stoughton Educational)Document448 pagesBurn - Lyric Age of Greece (1978, Hodder & Stoughton Educational)Lucas Díaz LópezNo ratings yet

- ,tom,. 8720312Document15 pages,tom,. 8720312DikshitNo ratings yet

- America's Race Problem (1901)Document198 pagesAmerica's Race Problem (1901)ElectrixNo ratings yet

- A 12-Pack Tour of Brewing in OshkoshDocument5 pagesA 12-Pack Tour of Brewing in OshkoshOshkosh BeerNo ratings yet

- Leichoudes Pronoia of The ManganaDocument17 pagesLeichoudes Pronoia of The ManganaRoman DiogenNo ratings yet

- History G11 Note Unit 7 - 9Document25 pagesHistory G11 Note Unit 7 - 9Ebsa Ademe100% (1)

- Shodhganga Temple DesignDocument51 pagesShodhganga Temple DesignUday DokrasNo ratings yet

- Ston Easton Park Lon180028Document28 pagesSton Easton Park Lon180028Kwok Kei WongNo ratings yet

- A Splendid ExchangeDocument96 pagesA Splendid ExchangeTranNo ratings yet

- African Resistance To Imperialism DBQDocument3 pagesAfrican Resistance To Imperialism DBQMolly WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Non-Woody Life-Form Contribution To Vascular Plant Species Richness in A Tropical American ForestDocument14 pagesNon-Woody Life-Form Contribution To Vascular Plant Species Richness in A Tropical American ForestAndres Felipe Herrera MottaNo ratings yet

- 031) (Day 3) Sankalp Current Affairs Envs Lec 3pdfDocument12 pages031) (Day 3) Sankalp Current Affairs Envs Lec 3pdfsrimanikanta418No ratings yet

- ABSTRACTS OF ORAL/POSTER PRESENTATIONS - 100th Indian Science CongressDocument235 pagesABSTRACTS OF ORAL/POSTER PRESENTATIONS - 100th Indian Science CongressDr. Ranjan BeraNo ratings yet

- Amphibians and Reptiles of Mexico: Diversity and ConservationDocument24 pagesAmphibians and Reptiles of Mexico: Diversity and ConservationAZUCENA QUINTANANo ratings yet

- Ecosystem Services: Dr. G. Kumaravelu, Full Time Member, State Planning Commission, Government of Tamil NaduDocument157 pagesEcosystem Services: Dr. G. Kumaravelu, Full Time Member, State Planning Commission, Government of Tamil NaduKumaravelu GNo ratings yet

- Grade 5 SLM Q2 Module 6 Interactions Among Living Things and Non Living EditedDocument21 pagesGrade 5 SLM Q2 Module 6 Interactions Among Living Things and Non Living EditedRenabelle Caga100% (2)

- ျမစ္ဆံုစီမံကိန္း EIA အစီရင္ခံစာ...Document945 pagesျမစ္ဆံုစီမံကိန္း EIA အစီရင္ခံစာ...ဒီမိုေဝယံ100% (1)

- Science Worksheet Gr7Document26 pagesScience Worksheet Gr7Abdelrhman AhmedNo ratings yet

- E e EssayDocument1 pageE e EssayGabriela LinaresNo ratings yet

- Media Archaeology Out of Nature - An Interview With Jussi ParikkaDocument14 pagesMedia Archaeology Out of Nature - An Interview With Jussi ParikkacanguropediaNo ratings yet

- Care and Feeding of Azaleas: TsutsusiDocument3 pagesCare and Feeding of Azaleas: TsutsusijoeNo ratings yet

- Impact of Bohol Irrigation System Project Phase 2 (BIS II) On Rice FarmingDocument1 pageImpact of Bohol Irrigation System Project Phase 2 (BIS II) On Rice FarmingIRRI_SSDNo ratings yet

- CO Learning Plan Science 7Document3 pagesCO Learning Plan Science 7Mefrel BaNo ratings yet

- Convention On Biological DiversityDocument9 pagesConvention On Biological DiversitykaiaceegeesNo ratings yet

- Species Extinction and AdaptationDocument14 pagesSpecies Extinction and AdaptationJhaymie NapolesNo ratings yet

- Plant Growth-Promoting MicrobesDocument41 pagesPlant Growth-Promoting Microbesjitey16372No ratings yet

- Ensc 201 ReportDocument72 pagesEnsc 201 ReportSansen Handag Jr.No ratings yet

- Dhyeya IAS UPSC IAS CSE Prelims Test Series 2020 Detailed ScheduleDocument32 pagesDhyeya IAS UPSC IAS CSE Prelims Test Series 2020 Detailed ScheduleDivyansh RaiNo ratings yet

- ENTREPRENUERSHIPDocument39 pagesENTREPRENUERSHIPMariejoy TagayNo ratings yet

- Approach Human: Ecosystem Health Glues Forget, Jean LebelDocument40 pagesApproach Human: Ecosystem Health Glues Forget, Jean LebelBruno ImbroisiNo ratings yet

- EcologyDocument12 pagesEcologyAhmed RashidNo ratings yet

- BROERSMA, M. PETERS, C. Introduction PDFDocument18 pagesBROERSMA, M. PETERS, C. Introduction PDFRafaela CordeiroNo ratings yet

- Draft Policy Esa 2021 EnglishDocument14 pagesDraft Policy Esa 2021 EnglishdewminiNo ratings yet

- HabibaDocument94 pagesHabibaMohammad ShoebNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of A CommunityDocument15 pagesCharacteristics of A CommunityAlirazaNo ratings yet

- Eutrophication (: MeiotrophicationDocument4 pagesEutrophication (: MeiotrophicationGrace Bing-ilNo ratings yet

- Macro Environmental FactorsDocument3 pagesMacro Environmental FactorsMargie Opay100% (1)

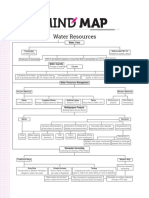

- Water Resources Mind MapDocument1 pageWater Resources Mind Mapanubhav deshwal100% (9)

- Unit 2 Ecosystem.Document41 pagesUnit 2 Ecosystem.Manav JainNo ratings yet

- Some Wild Animal Trade at The Environs of Shwesettaw Wildlife Sanctuary During Pagoda FestivalDocument4 pagesSome Wild Animal Trade at The Environs of Shwesettaw Wildlife Sanctuary During Pagoda FestivalInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Environmental Science CAPE SyllabusDocument61 pagesEnvironmental Science CAPE Syllabustevin_prawl75% (16)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ (Revised Edition)From EverandGut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ (Revised Edition)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (378)

- Tales from Both Sides of the Brain: A Life in NeuroscienceFrom EverandTales from Both Sides of the Brain: A Life in NeuroscienceRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (18)

- Periodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to ZincFrom EverandPeriodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to ZincRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (137)

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseFrom EverandDark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (69)

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionFrom EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (811)

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsFrom EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- A Series of Fortunate Events: Chance and the Making of the Planet, Life, and YouFrom EverandA Series of Fortunate Events: Chance and the Making of the Planet, Life, and YouRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (62)

- Water to the Angels: William Mulholland, His Monumental Aqueduct, and the Rise of Los AngelesFrom EverandWater to the Angels: William Mulholland, His Monumental Aqueduct, and the Rise of Los AngelesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (21)

- Smokejumper: A Memoir by One of America's Most Select Airborne FirefightersFrom EverandSmokejumper: A Memoir by One of America's Most Select Airborne FirefightersNo ratings yet

- 10% Human: How Your Body's Microbes Hold the Key to Health and HappinessFrom Everand10% Human: How Your Body's Microbes Hold the Key to Health and HappinessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (33)

- The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity--and Will Determine the Fate of the Human RaceFrom EverandThe Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity--and Will Determine the Fate of the Human RaceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (516)

- All That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving CrimesFrom EverandAll That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving CrimesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (397)

- The Other Side of Normal: How Biology Is Providing the Clues to Unlock the Secrets of Normal and Abnormal BehaviorFrom EverandThe Other Side of Normal: How Biology Is Providing the Clues to Unlock the Secrets of Normal and Abnormal BehaviorNo ratings yet

- The Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural DisasterFrom EverandThe Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural DisasterNo ratings yet

- Who's in Charge?: Free Will and the Science of the BrainFrom EverandWho's in Charge?: Free Will and the Science of the BrainRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (65)

- Undeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is DesignedFrom EverandUndeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is DesignedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- Crypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondFrom EverandCrypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Fast Asleep: Improve Brain Function, Lose Weight, Boost Your Mood, Reduce Stress, and Become a Better SleeperFrom EverandFast Asleep: Improve Brain Function, Lose Weight, Boost Your Mood, Reduce Stress, and Become a Better SleeperRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemFrom EverandMoral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (115)