Some Memories of Charles Dickens

The Atlantic's second editor, James T. Fields, pays fond tribute to his late friend

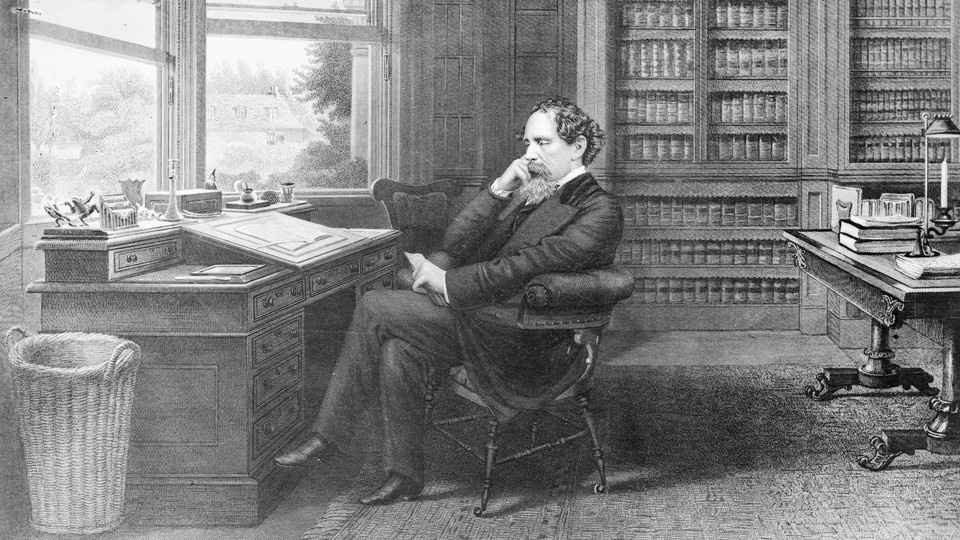

On a sunny morning in October last the writer of these recollections heard from the author's lips the first chapters of a new story, the concluding lines of which initial pages were then scarcely dry from the pen. The story is unfinished, and he who read that autumn morning with such vigor of voice and dramatic power is in his grave. This private reading took place in the little room where the great novelist for many years has been accustomed to write, and in the house where on a pleasant evening in June he died. The spot is one of the loveliest in Kent, and must always be remembered as the last residence of Charles Dickens. He used to declare his firm belief that Shakespeare was specially fond of Kent, and that the poet chose Gad's Hill and Rochester for the scenery of his plays from intimate personal knowledge of their localities. He said he had no manner of doubt but that one of Shakespeare's haunts was the old inn at Rochester, and that this conviction came forcibly upon him one night as he was walking that way, and discovered Charles's Wain over the chimney just as Shakespeare has described it, in words put into the mouth of the carrier in King Henry the Fourth. There is no prettier place than Gad's Hill in all England for the earliest and latest flowers, and Dickens chose it, when he had arrived at the fulness of his fame and prosperity, as the home in which he most wished to spend the remainder of his days. When a boy, he would often pass the house with his father, and frequently said to him, "If ever I have a dwelling of my own, Gad's Hill Place is the house I mean to buy." In that beautiful retreat he has for many years been accustomed to welcome his friends, and find relaxation from the crowded life of London. On the lawn playing at bowls, in the Swiss summer-house charmingly shaded by green leaves, he always seemed the best part of summer, beautiful as the season is in the delightful region where he lived. In a letter written not long ago to a friend in America he thus described his home:—

"Divers birds sing here all day, and the nightingales all night. The place is lovely, and in perfect order. I have put five mirrors in the Swiss chalet (where I write), and they reflect and refract, in all kinds of ways, the leaves that are quivering at the windows, and the great fields of waving corn, and the sail-dotted river. My room is up among the branches of the trees; and the birds and the butterflies fly in and out, and the green branches shoot in at the open windows, and the lights and shadows of the clouds come and go with the rest of the company. The scent of the flowers, and indeed of everything that is growing for miles and miles, is most delicious."

There he could be most thoroughly enjoyed, for he never seemed so cheerfully at home anywhere else. At his own table, surrounded by his family, and a few guests, old acquaintances from town,—among them sometimes Forster, Carlyle, Reade, Collins, Layard, Maclise, Stone, Macready, Talfourd,—he was always the choicest and liveliest companion. He was not what is called in society a professed talker, but he was something far better and rarer.

In his own inimitable manner he would frequently relate to a friend, if prompted, stories of his youthful days, when he was toiling on the London Morning Chronicle, passing sleepless hours as a reporter on the road in a post-chaise, driving day and night from point to point to take down the speeches of Shiel or O'Connell. He liked to describe the post-boys, who were accustomed to hurry him over the road that he might reach London in advance of his rival reporters, while, by the aid of a lantern, he was writing out for the press, as he flew over the ground, the words he had taken down in short-hand. Those were his days of severe training, when in rain and sleet and cold he dashed along, scarcely able to keep the blinding mud out of his tired eyes; and he imputed much of his ability for steady hard work to his practice as a reporter, kept at his grinding business, and determined if possible to earn seven guineas a week. A large sheet was started at this period of his life, in which all the important speeches of Parliament were to be reported verbatim for future reference. Dickens was engaged on this gigantic journal. Mr. Stanley had spoken at great length on the condition of Ireland. It was a very long and eloquent speech, occupying many hours in the delivery. Eight reporters were sent in to do the work. Each one was required to report three quarters of an hour, then to retire, write out his portion, and to be succeeded by the next. Young Dickens was detailed to lead off with the first part. It also fell to his lot, when the time came round, to report the closing portions of the speech. On Saturday the whole was given to the press, and Dickens ran down to the country for a Sunday's rest. Sunday morning had scarcely dawned, when his father, who was a man of immerse energy, made his appearance in his son's sleeping-room. Mr. Stanley was so dissatisfied with what he found in print, except the beginning and ending of his speech (just what Dickens had reported) that he sent immediately to the office and obtained the sheets of these parts of the report. He there found the name of the reporter, which, according to custom, was written on the margin. Then he requested that the young man bearing the name of Dickens should be immediately sent for. Dickens's father, all aglow with the prospect of probable promotion in the office, went immediately to his son's stopping-place in the country and brought him back to London. In telling the story, Dickens said: "I remember perfectly to this day the aspect of the room I was shown into, and the two gentlemen in it, Mr. Stanley and his father. Both gentlemen were extremely courteous to me, but I noted their evident surprise at the appearance of so young a man. While we spoke together, I had taken a seat extended to me in the middle of the room. Mr. Stanley told me he wished to go over the whole speech and have it written out by me, and if I were ready he would begin now. Where would I like to sit? I told him I was very well where I was, and we could begin immediately. He tried to induce me to sit at a desk, but at that time in the House of Commons there was nothing but one's knees to write upon, and I had formed the habit of doing my work in that way. Without further pause he began and went rapidly on, hour after hour, to the end, often becoming very much excited and frequently bringing down his hand with great violence upon the desk near which he stood."

No writer ever lived whose method was more exact, whose industry was more constant, and whose punctuality was more marked, than those of Charles Dickens. He never shirked labor, mental or bodily. He rarely declined, if the object were a good one, taking the chair at a public meeting, or accepting a charitable trust. Many widows and orphans of deceased literary men have for years been benefited by his wise trusteeship or counsel, and he spent a great portion of his time personally looking after the property of the poor whose interests were under his control. He was, as has been intimated, one of the most industrious of men, and marvellous stories are told (not by himself) of what he has accomplished in a given time in literary and social matters. His studies were all from nature and life, and his habits of observation were untiring. If he contemplated writing Hard Times, he arranged with the master of Astley's circus to spend many hours behind the scenes with the riders and among the horses; and if the composition of the Tale of Two Cities were occupying his thoughts, he could banish himself to France for two years to prepare for that great work. Hogarth pencilled on his thumb-nail a striking face in a crowd that he wished to preserve; Dickens with his transcendent memory chronicled in his mind whatever of interest met his eye or reached his ear, any time or anywhere. Speaking of memory one day, he said the memory of children was prodigious; it was a mistake to fancy children ever forgot anything. When he was delineating the character of Mrs. Pipchin, he had in his mind an old lodging-house keeper in an English watering-place where he was living with his father and mother when he was but two years old. After the book was written he sent it to his sister, who wrote back at once: "Good heavens! what does this mean? you have painted our lodging-house keeper, and you were but two years old at that time!" Characters and incidents crowded the chambers of his brain, all ready for use when occasion required. No subject of human interest was ever indifferent to him, and never a day went by that did not afford him some suggestion to be utilized in the future.

His favorite mode of exercise was walking; and when in America, two years ago, scarcely a day passed, no matter what the weather, that he did not accomplish his eight or ten miles. It was on these expeditions that he liked to recount to the companion of his rambles stories and incidents of his early life; and when he was in the mood, his fun and humor knew no bounds. He would then frequently discuss the numerous characters in his delightful books, and would act out, on the road, dramatic situations, where Nickleby or Copperfield or Swivelier would play distinguished parts. It is remembered that he said, on one of these occasions, that during the composition of his first stories he could never entirely dismiss the characters about whom he happened to be writing; that while the Old Curiosity Shop was in process of composition Little Nell followed him about everywhere; that while he was writing Oliver Twist Fagin the Jew would never let him rest, even in his most retired moments; that at midnight and in the morning, on the sea and on the land, Tiny Tim and Little Bob Cratchit were ever tugging at his coat-sleeve, as if impatient for him to get back to his desk and continue the story of their lives. But he said after he had published several books, and saw what serious demands his characters were accustomed to make for the constant attention of his already overtasked brain, he resolved that the phantom individuals should no longer intrude on his hours of recreation and rest, but that when he closed the door of his study he would shut them all in, and only meet them again when he came back to resume his task. That force of will with which he was so pre-eminently endowed enabled him to ignore these manifold existences till he chose to renew their acquaintance. He said, also, that when the children of his brain had once been launched, free and clear of him, into the world, they would sometimes turn up in the most unexpected manner to look their father in the face.

Sometimes he would pull the arm of his companion and whisper, "Let us avoid Mr. Pumblechook, who is crossing the street to meet us"; or, "Mr. Micawber is coming; let us turn down this alley to get out of his way." He always seemed to enjoy the fun of his comic people, and had unceasing mirth over Mr. Pickwick's misadventures. In answer one day to a question, prompted by psychological curiosity, if he ever dreamed of any of his characters, his reply was, "Never; and I am convinced that no writer (judging from my own experience, which cannot be altogether singular, but must be a type of the experience of others) has ever dreamed of the creatures of his own imagination. It would," he went on to say, "be like a man's dreaming of meeting himself, which is clearly an impossibility. Things exterior to one's self must always be the basis of dreams." The growing up of characters in his mind never lost for him a sense of the marvellous. "What an unfathomable mystery there is in it all!" he said one day. Taking up a wineglass, he continued: "Suppose I choose to call this a character, fancy it a man, endue it with certain qualities; and soon the fine filmy webs of thought, almost impalpable, coming from every direction, we know not whence, spin and weave about it, until it assumes form and beauty, and becomes instinct with life."

In society Dickens rarely referred to the traits and characteristics of people he had known; but during a long walk in the country he delighted to recall and describe the peculiarities, eccentric and otherwise, of dead and gone as well as living friends. Then Sydney Smith and Jeffrey and Christopher North and Talfourd and Hood and Rogers seemed to live over again in his vivid reproductions, made so impressive by his marvellous memory and imagination. As he walked rapidly along the road, he appeared to enjoy the keen zest of his companion in the numerous impersonations with which he was indulging him.

He always had much to say of animals as well as of men, and there were certain dogs and horses he had met and known intimately which it was specially interesting to him to remember and picture. There was a particular dog in Washington which he was never tired of delineating. The first night Dickens read in the Capital this dog attracted his attention. "He came into the hall by himself," said he, "got a good place before the reading began, and paid strict attention throughout. He came the second night, and was ignominiously shown out by one of the check-takers. On the third night he appeared again with another dog, which he had evidently promised to pass in free; but you see," continued Dickens, "upon the imposition being unmasked, the other dog apologized by a howl and withdrew. His intentions, no doubt, were of the best, but he afterwards rose to explain outside, with such inconvenient eloquence to the reader and his audience, that they were obliged to put him down stairs."

In a letter written during his reading tour in America, in 1868, and dated from Albany, he says: "We had all sorts of adventures by the way, among which two of the most notable were: 1. Picking up two trains out of the water, in which the passengers had been composedly sitting all night, until relief should arrive. 2. Unpacking and releasing into the open country a great train of cattle and sheep that had been in the water I don't know how long, and that had begun in their imprisonment to eat each other. I never could have realized the strong and dismal expressions of which the faces of sheep are capable, had I not seen the haggard countenances of this unfortunate flock, as they were tumbled out of their dens and picked themselves up, and made off, leaping wildly (many with broken legs) over a great mound of frozen snow, and over the worried body of a deceased companion. Their misery was so very human, that I was sorry to recognize several intimate acquaintances conducting themselves in this forlornly gymnastic manner." He was such a firm believer in the mental faculties of animals, that it would have gone hard with a companion with whom he was talking, if a doubt were thrown, however inadvertently, on the mental intelligence of any four-footed friend that chanced to be at the time the subject of conversation. All animals which he took under his especial patronage seemed to have a marked affection for him. Quite a colony of dogs has always been a feature at Gad's Hill. When Dickens returned home from his last visit to America, these dogs were frequently spoken of in his letters. In May, 1868, he writes: "As you ask me about the dogs, I begin with them. The two Newfoundland dogs coming to meet me, with the usual carriage and the usual driver, and beholding me coming in my usual dress out at the usual door, it struck me that their recollection of my having been absent for any unusual time was at once cancelled. They behaved (they are both young dogs) exactly in their usual manner; coming behind the basket phaeton as we trotted along, and lifting their heads to have their ears pulled,—a special attention which they receive from no one else. But when I drove into the stable-yard, Linda (the St. Bernard) was greatly excited, weeping profusely, and throwing herself on her back that she might caress my foot with her great fore-paws. M.'s little dog, too, Mrs. Bouncer, barked in the greatest agitation, on being called down and asked, 'Who is this?' tearing round and round me like the dog in the Faust outlines."

In many walks and talks with Dickens, his conversation, now, alas! so imperfectly recalled, frequently ran on the habits of birds, the raven, of course, interesting him particularly. He always liked to have a raven hopping about his grounds, and whoever has read the new Preface to Barnaby Rudge, must remember several of his old friends in that line. He had quite a fund of canary-bird anecdotes, and the pert ways of birds that picked up worms for a living afforded him infinite amusement. He would give a capital imitation of the way a robin-redbreast cocks his head on one side preliminary to a dash forward in the direction of a wriggling victim. There is a small grave at Gad's Hill to which Dickens would occasionally take a friend, and it was quite a privilege to stand with him beside the burial-place of little Dick, the family's favorite canary.

There were certain books of which Dickens liked to talk during his walks. Among his especial favorites were the writings of Cobbett, DeQuincey, the Lectures on Moral Philosophy by Sydney Smith, and Carlyle's French Revolution. Of this latter Dickens said it was the book of all others which he read perpetually and of which he never tired,— the book which always appeared more imaginative in proportion to the fresh imagination he brought to it, a book for inexhaustibleness to be placed before every other book. When writing the Tale of Two Cities he asked Carlyle if he might see one of the books to which he referred in his history; whereupon Carlyle packed up and sent down to Gad's Hill all his reference volumes, and Dickens read them faithfully. But the more he read the more he was astonished to find how the facts had passed through the alembic of Carlyle's brain and had come out and fitted themselves, each as a part of one great whole, making a compact result, indestructible and unrivalled; and he always found himself turning away from the books of reference, and re-reading with increased wonder this marvellous new growth. There were certain books particularly hateful to him, and of which he never spoke except in terms of most ludicrous raillery. Mr. Barlow, in Sandford and Merton, he said was the favorite enemy of his boyhood and his first experience of a bore. He had an almost supernatural hatred for Barlow, "because he was so very instructive, and always hinting doubts with regard to the veracity of "Sindbad the Sailor," and had no belief whatever in 'The Wonderful Lamp' or 'The Enchanted Horse.'" Dickens rattling his mental cane over the head of Mr. Barlow was as much better than any play as can be well imagined. He gloried in many of Hood's poems, especially in that biting Ode to Rae Wilson, and he would gesticulate with a fine fervor the lines,

"... the hypocrites who ope Heaven's door

Obsequious to the sinful man of riches,—

But put the wicked, naked, bare-legged poor

In parish stocks instead of breeches."

One of his favorite books was Pepys's Diary, the curious discovery of the key to which, and the odd characteristics of its writer, were a never-failing source of interest and amusement to him. The vision of Pepys hanging round the door of the theatre, hoping for an invitation to go in, not being able to keep away in spite of a promise he had made to himself that he would spend no more money foolishly, delighted him. Speaking one day of Gray, the author of the Elegy, he said: "No poet ever came walking down to posterity with so small a book under his arm." He preferred Smollett to Fielding, putting Peregrine Pickle above Tom Jones. Of the best novels by his contemporaries he always spoke with warm commendation, and Griffith Gaunt he thought a production of very high merit. He was "hospitable to the thought" of all writers who were really in earnest, but at the first exhibition of floundering or inexactness he became an unbeliever. People with dislocated understandings he had no tolerance for.

He was passionately fond of the theatre, loved the lights and music and flowers, and the happy faces of the audience; he was accustomed to say that his love of the theatre never failed, and, no matter how dull the play, he was always careful while he sat in the box to make no sound which could hurt the feelings of the actors, or show any lack of attention. His genuine enthusiasm for Mr. Fechter's acting was most interesting. He loved to describe seeing him first, quite by accident, in Paris, having strolled into a little theatre there one night. "He was making love to a woman," Dickens said, "and he so elevated her as well as himself by the sentiment in which he enveloped her, that they trod in a purer ether,and in another sphere, quite lifted out of the present. 'By heavens!' I said to myself, 'a man who can do this can do anything.' I never saw two people more purely and instantly elevated by the power of love. The manner, also," he continued, "in which he presses the hem of the dress of Lucy in the Bride of Lammermoor is something wonderful. The man has genius in him which is unmistakable."

Life behind the scenes was always a fascinating study to Dickens. "One of the oddest sights a green-room can present," he said one day, "is when they are collecting children for a pantomime. For this purpose the prompter calls together all the women in the ballet, and begins giving out their names in order, while they press about him eager for the chance of increasing their poor pay by the extra pittance their children will receive. 'Mrs. Johnson, how many?' 'Two, sir.' 'What ages?' 'Seven and ten.' 'Mrs. B., how many?' and so on, until the required number is made up. The people who go upon the stage, however poor their pay or hard their lot, love it too well ever to adopt another vocation of their free-will. A mother will frequently be in the wardrobe, children in the pantomime, elder sisters in the ballet, etc."

Dickens's habits as a speaker differed from those of most orators. He gave no thought to the composition of the speech he was to make till the day before he was to deliver it. No matter whether the effort was to be a long or a short one, he never wrote down a word of what he was going to say; but when the proper time arrived for him to consider his subject, he took a walk into the country and the thing was done. When he returned he was all ready for his task.

He liked to talk about the audiences that came to hear him read, and he gave the palm to his Parisian one, saying it was the quickest to catch his meaning. Although he said there were many always present in his room in Paris who did not fully understand English, yet the French eye is so quick to detect expression that it never failed instantly to understand what he meant by a look or an act. "Thus, for instance," he said, "when I was impersonating Steerforth in David Copperfield, and gave that peculiar grip of the hand to Emily's lover, the French audience burst into cheers and rounds of applause." He said with reference to the preparation of his readings, that it was three months' hard labor to get up one of his own stories for public recitation, and he thought he had greatly improved his presentation of the Christmas Carol while in this country. He considered the storm scene in David Copperfield one of the most effective of his readings. The character of Jack Hopkins in Bob Sawyer's Party he took great delight in representing.

It gave him a natural pleasure when he heard quotations from his own books introduced without effort into conversation. He did not always remember, when his own words were quoted, that he was himself the author of them, and appeared astounded at the memory of others in this regard. He said Mr. Secretary Stanton had a most extraordinary knowledge of his books and a power of taking the text up at any point, which he supposed to belong to only one person, and that person not himself.

It was said of Garrick that he was the cheerfullest man of his age. This can be as truly said of Charles Dickens. In his presence there was perpetual sunshine, and gloom was banished as having no sort of relationship with him. No man suffered more keenly or sympathized more fully than he did with want and misery; but his motto was, "Don't stand and cry; press forward and help remove the difficulty." The speed with which he was accustomed to make the deed follow his yet speedier sympathy was seen pleasantly on the day of his visit to the School-ship in Boston Harbor. He said, previously to going on board that ship, nothing would tempt him to make a speech, for he should always be obliged to do it on similar occasions, if he broke through his rule so early in his reading tour. But Judge Russell had no sooner finished his simple talk, to which the boys listened, as they always do, with eager faces, than Dickens rose as if he could not help it, and with a few words so magnetized them that they wore their hearts in their eyes as if they meant to keep the words forever. An enthusiastic critic once said of John Ruskin, "that he could discover the Apocalypse in a daisy." As noble a discovery may be claimed for Dickens. He found all the fair humanities blooming in the lowliest hovel. He never put on the good Samaritan: that character was native to him. Once while in this country, on a bitter, freezing afternoon,—night coming down in a drifting snow-storm,—he was returning from a long walk in the country with a single companion. The wind and baffling sleet were so furious that the street in which they happened to be fighting their way was quite deserted; it was almost impossible to see across it, the air was so thick with the tempest; all conversation between the friends had ceased, for it was only possible to breast the storm by devoting their whole energies to keeping on their feet; they seemed to be walking in a different atmosphere from any they had ever before encountered. All at once Dickens was missed from his companion's side. What had become of him? Had he gone down in the drift, utterly exhausted, and was the snow burying him out of sight? Very soon the sound of his cheery voice was heard on the other side of the way. With great difficulty, over the piled-up snow, his companion struggled across the street, and there found him lifting up, almost by main force, a blind old man who had got bewildered by the storm, and had fallen down unnoticed, quite unable to proceed. Dickens, a long distance away from him, with that tender, sensitive, and penetrating vision, ever on the alert for suffering in any form, had rushed at once to the rescue, comprehending at a glance the situation of the sightless man. To help him to his feet and aid him homeward in the most natural and simple way afforded Dickens such a pleasure as only the benevolent by intuition can understand.

Throughout his life Dickens was continually receiving tributes from those he had benefited, either by his books or by his friendship. There is an odd and very pretty story (vouched for here as true) connected with the influence he so widely exerted. Last winter, soon after he came up to London to reside for a few months, he received a letter from a man telling him that he had begun life in the most humble way possible, and that he considered he owed his subsequent great success and such education as he had given himself entirely to the encouragement and cheering influence he had derived from Dickens's books, of which he had been a constant reader from his childhood. He had been made a partner in his master's business, and when the head of the house died, the other day, it was found he had left the whole of his large property to this man. As soon as he came into possession of this fortune, his mind turned to Dickens, whom he looked upon as his benefactor and teacher, and his first desire was to tender him some testimonial of gratitude and veneration. He then begged Dickens to accept a large sum of money. Dickens declined to receive the money, but his unknown friend sent him instead two silver table ornaments of great intrinsic value bearing this inscription: "To Charles Dickens, from one who has been cheered and stimulated by his writings, and held the author amongst his first Remembrances when he became prosperous." One of these silver ornaments was supported by three figures, representing three seasons. In the original design there were, of course, four, but the donor was so averse to associating the idea of Winter in any sense with Dickens that he caused the workman to alter the design and leave only the cheerful seasons. No event in the great author's career was ever more gratifying and pleasant to him.

His friendly letters were exquisitely turned, and are among his most charming compositions. They abound in felicities only like himself. In 1860 he writes to an American traveller sojourning in Italy: "I should like to have a walk through Rome with you this bright morning (for it really is bright in London), and convey you over some favorite ground of mine. I used to go up the street of Tombs, past the tomb of Cecilia Metella, away out upon the wild campagna, and by the old Appian Road (easily tracked out among the ruins and primroses), to Albano. There, at a very dirty inn, I used to have a very dirty lunch, generally with the family's dirty linen lying in a corner, and inveigle some very dirty Vetturino in sheep-skin to take me back to Rome."

Writing from a Western city in 1868, he says: "The hotel here is a dreary institution, but I have an impression we must be in the wrong one, and buoy myself up with a devout belief in the other over the way. The awakening to consciousness this morning on a lop-sided bedstead facing nowhere, in a room holding nothing but sour dust, was more terrible than the being afraid to go to bed last night. To keep ourselves up, we played whist (double dummy) until neither of us could bear to speak to the other any more. We had previously supped on a tough old nightmare, named Buffalo. What do you think of a 'fowl de poulet'? or a 'Paettie de Shay'? or 'celary'? or 'murange with cream'? Because all these delicacies are in the printed bill of fare! We asked the Irish waiter what 'Paettie de Shay' was, and he said it was 'the Frinch name the steward giv' to oyster pattie.'"

In a letter written during his last course of readings in various parts of England he wrote: "B—— (setting aside remembrances of Roderick Random and Humphrey Clinker) looked, I fancied, just as if a cemetery full of old people had somehow made a successful rise against Death, carried the place by assault, and built a city with the gravestones; in which they were trying to look alive, but with very indifferent success."

In a little note to a friend who had been consulting him the day before about the purchase of some old furniture in London he wrote: "There is a chair (without a bottom) at a shop near the office, which I think would suit you. It cannot stand of itself, but will almost seat somebody, if you put it in a corner, and prop one leg up with two wedges and cut another leg off. The proprietor asks £20, but says he admires literature and would take £18. He is of republican principles and I think would take £17 19 s. 6 d., from a cousin; shall I secure this prize? It is very ugly and wormy, and it is related, but without proof, that on one occasion Washington declined to sit down in it."

After his return home from America he was constantly boasting in his letters of his renewed health. In one of them he says: "I am brown now beyond belief, and cause the greatest disappointment in all quarters by looking so well. It is really wonderful what those fine days at sea did for me. My doctor was quite broken down in spirits when he saw me for the first time since my return last Saturday. 'Good heavens,' he said, recoiling, 'seven years younger!'"

Bright colors were a constant delight to him; and the gay hues of flowers were those most welcome to his eye. When the rhododendrons were in bloom in Cobham Park, the seat of his friend and neighbor, Lord Darnley, he always counted on taking his guests there to enjoy the magnificent show. In a letter dated in April, 1869, he says to a friend who anticipated making him a visit from America: "Please look sharp in the matter of landing on this used-up, worn-out, and rotten old parient. I rather think that when the 12th of June shall have shaken off these shackles" (he was then reading in London) "there will be borage on the lawn at Gad's. Your heart's desires in that matter and in the minor particulars of Cobbam Park, Rochester Castle, and Canterbury shall be fulfilled, please God! The red jackets shall turn out again on the turnpike road, and picnics among the cherry orchards and hop gardens shall be heard of in Kent." (He delighted to turn out for the delectation of his Transatlantic cousins a couple of postilions in the old red jackets of the old red royal Dover road, making the ride as much as possible like a holiday drive in England fifty years ago.)

When in the mood for humorous characterization, Dickens's hilarity was most amazing. To hear him tell a ghost story with a very florid imitation of a very pallid ghost, or hear him sing an old-time stage song, such as he used to enjoy in his youth at a cheap London theatre, to see him imitate a lion in a menagerie-cage, or the clown in a pantomime when he flops and folds himself up like a jack-knife, or to join with him in some mirthful game of his own composing, was to become acquainted with one of the most delightful and original companions in the world.

On one occasion, during a walk, he chose to run into the wildest of vagaries about conversation. The ludicrous vein he indulged in during that two hours' stretch can never be forgotten. Among other things, he said he had often thought how restricted one's conversation must become when one was visiting a man who was to be hanged in half an hour. He went on in a most surprising manner to imagine all sorts of difficulties in the way of becoming interesting to the poor fellow. "Suppose," said he, "it should be a rainy morning while you are making the call, you could not possibly indulge in the remark, 'We shall have fine weather to-morrow, sir,' for what would that be to him? For my part, I think," said he, "I should confine my observations to the days of Julius Caesar or King Alfred."

At another time when speaking of what was constantly said about him in certain newspapers, he observed: "I notice that about once in every seven years I become the victim of a paragraph disease. It breaks out in England, travels to India by the overland route, gets to America per Cunard line, strikes the base of the Rocky Mountains, and rebounding back to Europe, mostly perishes on the steppes of Russia from inanition and extreme cold." When he felt he was not under observation, and that tomfoolery would not be frowned upon or gazed at with astonishment, he gave himself up without reserve to healthy amusement and strengthening mirth. It was his mission to make people happy. Words of good cheer were native to his lips, and he was always doing what he could to lighten the lot of all who came into his beautiful presence. His talk was simple, natural, and direct, never dropping into circumlocution nor elocution. Now that he is gone, whoever has known him intimately for any considerable period of time will linger over his tender regard for, and his engaging manner with, children; his cheery "Good Day" to poor people he happened to be passing in the road; his trustful and earnest "Please God," when he was promising himself any special pleasure, like rejoining an old friend or returning again to scenes he loved. At such times his voice had an irresistible pathos in it, and his smile diffused a sensation like music. When he came into the presence of squalid or degraded persons, such as one sometimes encounters in almshouses or prisons, he had such soothing words to scatter here and there, that those who had been "most hurt by the archers" listened gladly, and loved him without knowing who it was that found it in his heart to speak so kindly to them.

Oftentimes during long walks in the streets and by-ways of London, or through the pleasant Kentish lanes, or among the localities he has rendered forever famous in his books, his companion has recalled the sweet words in which Shakespeare has embalmed one of the characters in Love's Labor Lost:—

"A merrier man,

Within the limit of becoming mirth,

I never spent an hour's talk withal:

His eye begets occasion for his wit;

For every object that the one doth catch

The other turns to a mirth-moving jest,

Which his fair tongue, conceit's expositor,

Delivers in such apt and gracious words

That aged ears play truant at his tales,

And younger hearings are quite ravishéd;

So sweet and voluble is his discourse."

Twenty years ago Daniel Webster said that Dickens had already done more to ameliorate the condition of the English poor than all the statesmen Great Britain had sent into Parliament. During the unceasing demands upon his time and thought, he found opportunities of visiting personally those haunts of suffering in London which needed the keen eye and sympathetic heart to bring them before the public for relief. Whoever has accompanied him on his midnight walks into the cheap lodging-houses provided for London's lowest poor cannot have failed to learn lessons never to be forgotten. Newgate and Smithfield were lifted out of their abominations by his eloquent pen, and many a hospital is to-day all the better charity for having been visited and watched by Charles Dickens. To use his own words, through his whole life he did what he could "to lighten the lot of those rejected ones whom the world has too long forgotten and too often misused."

These inadequate, and, of necessity, hastily written, records must suffice for the present and stand for what they are worth as personal recollections of the great author who has made so many millions happy by his inestimable genius and sympathy. His life will no doubt be written out in full by some competent hand in England; but however numerous the volumes of his biography, the half can hardly be told of the good deeds he has accomplished for his fellow-men.

And who could ever tell, if those volumes were written, of the subtle qualities of insight and sympathy which rendered him capable of friendship above most men,—which enabled him to reinstate its ideal, and made his presence a perpetual joy, and separation from him an ineffaceable sorrow?