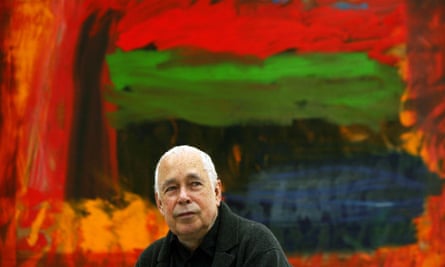

Sir Howard Hodgkin, who has died aged 84, was literally a broad-brush artist, the width of whose lush, pigment-loaded strokes was accentuated in all but the later paintings by the smallness of the surface. Their impact was intensified by his habit of incorporating the frame, actual or suggested, as part of the picture.

Like Francis Bacon, though, it pleased Hodgkin to refer to himself as a figurative painter; and, as with Bacon’s suggestion that his own smeared agonies were realist, Hodgkin’s use of the term figurative seemed to most viewers of these sumptuously coloured abstractions nothing more than a tease. If so, it was a tease that they enjoyed, because his prime Hodgkin became one of the most popular artists in Britain, with many successful shows abroad as well, particularly in the US, Germany, and Italy, where in 1984 he represented his country in an acclaimed show at the Venice Biennale.

A few, very few, critics raised their voices in dissent against the background of loud popular and critical acclaim. It may be that Hodgkin’s finest legacy will turn out to have been the mural he created for the British Council building in New Delhi by the Indian architect Charles Correa. Within an open loggia to the front of the building, behind a large cut-out keyhole shape, Hodgkin painted a bold, flat monochrome pattern that might represent a great banyan tree; the shadowed informality of the painting makes something lyrical of Correa’s manifestly modernist austerity.

With his singular approach to painting Hodgkin was certainly out of step when he was studying at Camberwell School of Art in London, where Euston Road impressionism was the order of the day. He claimed ever after to have remained an outsider, despite his appointment as CBE (1976), a knighthood (1992) and being made a Companion of Honour (2003), with trusteeships, successively, of the Tate and the National Gallery, appearances on TV’s The South Bank Show, with Melvyn Bragg, and Arena, with Alan Yentob, and sundry honorary fellowships and doctorates.

In a similar vein, he always said he had come from humble circumstances, despite the evidence of his background: his mother, Katharine, was the daughter of a lord chief justice, Gordon Hewart (Viscount Hewart); his father, Eliot Hodgkin, it is true, seems to have disliked his day job with ICI, but he was a keen plant collector and picked up a Victoria gold medal from the Royal Horticultural Society. The extended Hodgkin family included Thomas Hodgkin, the physician after whom the lymph node cancers Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin were named and the artist and critic Roger Fry. The conductor John Eliot Gardiner was a cousin.

Hodgkin’s incidental connection to the Bloomsbury set, reinforced by his own studio’s Bloomsbury address, would later bring him grief at the hands of some critics, who wanted to see in his paintings an equivalent to the domestic designs produced for Fry’s Omega Workshops.

If the spoon in Hodgkin’s mouth at birth was merely silver-plated, it was nevertheless a privileged childhood. In 1940 his mother took Howard and his sister, Ann, away from the threatened bombing of London, their birthplace, to the US and a life on Long Island in the house, he later said, where Scott Fitzgerald set The Great Gatsby. He had already, at the age of five, decided that he would be an artist. When he was taken to New York to visit the Museum of Modern Art and saw Matisse’s painting Piano Lesson, his decision became irrevocable, despite his mother’s apparently irrational desire for him to become a diplomat. “I would have started a war,” he said, and he was indeed quick to anger.

When he returned to Britain he was sent to Eton, where the drawing master was Wilfrid Blunt. He introduced his pupil to Indian art and, starting young, Hodgkin amassed a famous collection of Mughal-derived Pahari painting from the Himalayas. The interest extended to India itself, which he visited regularly over the years. His education proper began in 1949 at Camberwell, followed by the Bath Academy of Art at Corsham (1950-54), where his teachers included William Scott, and where he too later taught for a while. In 1955 he married a fellow Corsham student, Julia Lane.

Hodgkin’s early spiky style of figures in interiors is still regarded by a few quirky admirers as his best work. Possibly the earliest of these is Memoirs, painted in 1949 when he was only 16. It shows, awkwardly and unappealingly, the young Hodgkin, with an old head on his shoulders, in a chair and listening to his hostess, who reclines on a sofa in the Gatsby house, confessing her (apparently fictitious) life of sexual affairs. Hodgkin said that the experience of painting it was when he realised that his subject would always be memory.

Despite appearances, he was for many years a slow worker, constantly reformulating and repainting and producing no more than nine or 10 pictures a year. He was 30 before he had his first solo show. When he did, it was with Arthur Tooth, at that time just about the most distinguished commercial gallery in London. By 1976, when Nicholas Serota, then director of the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, gave him his first museum show, Hodgkin had made his breakthrough to the mature style for which he became known. While he initially scorned the tradition of easel painting, Hodgkin came round to the view that his own works were artefacts, objects of contemplation. Having started by painting the frames, he discarded canvas and used wood as the painting’s surface – old table tops, breadboards, and in one case, The Moon (1978-80), the wooden back of an old clock. This, paradoxically, was one of his more snail-like productions, but one of the best.

Hodgkin’s friend, the writer Bruce Chatwin, related the burgeoning of Hodgkin’s mature style at this period to the occasion when, having had a homoerotic experience, he felt emotionally liberated. In 1978 Hodgkin separated from Lane, leaving her with two sons, Louis and Sam, (this severance from her seems to have shadowed with sorrow the rest of his life) and in 1983 he settled into a lifetime partnership with the music critic Antony Peattie. Yet Hodgkin himself denied a direct connection between coming out as a gay man and the development of his painting. Nonetheless, many of his works became clearly erotic and some, like None But the Brave Deserves the Fair, and Waking Up in Naples, refer to sexual encounters.

The structural underpinning lay in Hodgkin’s reverence for the work of Edouard Vuillard, the French intimiste painter who, like Pierre Bonnard, set paintings in domestic interiors. Hodgkin acknowledged that the bands and blotches of colour in his paintings could be taken as enlargements of Vuillard’s touch, but the influence stretched to the closeted intensity of the surfaces of Vuillard’s painting, accentuated in Hodgkin by the sense of depth imparted by his integral framing.

By 1984 Hodgkin had accumulated enough work to fill the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. That year, too, he was the favourite to win the first Turner prize, but instead it went to the US-based British painter Malcolm Morley; Hodgkin won the following year.

For someone in whom so many influences have been detected, from Turner to Seurat, Vuillard to Matisse, and, in their great splashes and swaths of colour, Ivon Hitchens and Peter Lanyon, Hodgkin’s paintings are instantly recognisable as his alone. The titles are usually meaningless to anybody but the artist, though some, such as Bombay Sunset (1972-73), are obvious. Many refer to meetings with friends, and occasionally have disconcerting figurative elements, such as the sketched bespectacled head dimly discerned in the painting DH in Hollywood, 1979-85. DH being his old friend David Hockney.

To Hodgkin, the title was always the clue to the picture: each refers to the experience that triggered the painting. “Mostly painting is like putting a message into a bottle and flinging it into the sea,” he told the Observer in 2001, but his paintings do very much recall the experience of living a well-to-do life of travel and dining out at friends’ houses or in plush restaurants – tropical skies, palm trees, lavish sunsets – in exotic locations such as Bombay, Kerala, Venice, Morocco and New York.

Like so many painters, Hodgkin felt liberated by the 1959 Tate show The New American Painting and by the impact of the scale and confidence of the abstract expressionists Barnett Newman and Jackson Pollock, though until the 1990s he continued to paint within a pre-abstract expressionist intimacy of format, and gained power from that containment. He added a rider: hang too many paintings together and they tend to kill each other. That certainly seemed a major lesson both of the big Hodgkin retrospective at the Hayward Gallery in 1997 and the Tate Britain show in 2006.

As Susan Sontag observed in the catalogue of another big show in Fort Worth, Texas: “Each picture is, ideally, a maximum seduction ... the viewer may be tempted to solve the problem, abandoning the proper distance at which all the picture’s charms may be appreciated to zero in for immersion in sheer colour bliss – what Hodgkin’s pictures can always be counted on to provide.”

Not quite always: there are bad paintings, ruined by a jarring note, an unassimilated white, say, or large dabbed and stabbed dots which go nowhere and do nothing but pile up into a constipated occlusion. Later in life he rid himself of his constant itch to paint and repaint and produced much freer and often bigger paintings that really were a sight for sore eyes. Hodgkin was not only a survivor, but a developer. In 1962 the ICA set up a show of the work of Allen Jones and Hodgkin. Jones looked much the better: better colourist, wittier, more succinct. Yet, successful as Jones became, he never achieved Hodgkin’s superstar status.

He was fortunate in his fan club, which included not only critics such as Robert Hughes, who acclaimed him in his Time magazine review of the Venice Biennale, but also, in a book called Writers on Howard Hodgkin (2006), a clutch of authors including Julian Barnes, William Boyd, James Fenton, Alan Hollinghurst and Colm Tóibín, whose prose was, as the Financial Times noted in what may not have been intended as a double-edged remark, as lush as Hodgkin’s paintings. At the time of his death the Gagosian was showing his work in Hong Kong, and a major show of his portraits opens at the National Portrait Gallery in London on 23 March.

He is survived by Antony and his children.