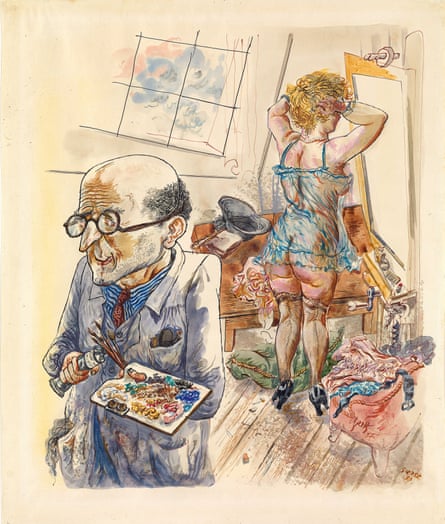

In a self-portrait that he sketched in the 1930s, George Grosz is getting ready to paint a model in his studio. As she does her hair, standing with her back to him and us, naked except for a translucent green slip that half covers her buttocks, seamed stockings and shoes, he grins lasciviously, squeezing a phallic paint tube. A rag hangs from his pocket like a masturbatory spurt. What a degenerate.

I mean that precisely. In 1937, Grosz, like many of the artists in Tate Modern’s often astonishing display of early 20th-century German art, had his works held up for mockery and revilement by the Nazis in their Munich exhibition Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art).

Magic Realism, a free display that has the depth of an exhibition, complete with scholarly catalogue, uncovers what scared the Nazis about modern German art. The Degenerate Art exhibition is remembered today simply as an attack on modernism. However, that is a bloodless misunderstanding. The reason the Nazis called modern art degenerate is that avant garde works in Germany after the first world war really did revel in the perverse, the decadent, the depraved. This art was not abstract but fiercely carnal and it is still shocking today.

Otto Dix’s 1922 watercolour Lustmord (Lust Murder) depicts a slavering Jack the Ripper figure with his tongue hanging out as he poses demonically by the woman he has killed. The artist relishes the contours of her corpse. Dix is the true murderer, for he has created this scene, his brush lingering over bloodstained flesh.

This is not the only “lust murder” on show. An etching by Dix shows a crazed murderer surrounded by dismembered body parts. An eerie 1924 drawing by Rudolf Schlichter portrays the artist sitting and contemplating two dead women who hang from his ceiling.

What sickened the imaginations of these artists? A touching early work by Dix reminds us of the horror they had endured. He was a machine gunner on the western front when he painted a portrait of his commanding officer, Bruno Alexander Roscher, in 1915. The story goes that it won him some welcome leave. Roscher’s face is like a piece of pink meat bulging out of his medal-bedecked uniform.

Dix returned from the war with a terrible sense of the fragile flesh we are. He was to record what he saw in grisly prints featuring worm-infested skulls and bodies on barbed wire. His images of sexual violence could be understood as post-traumatic nightmares.

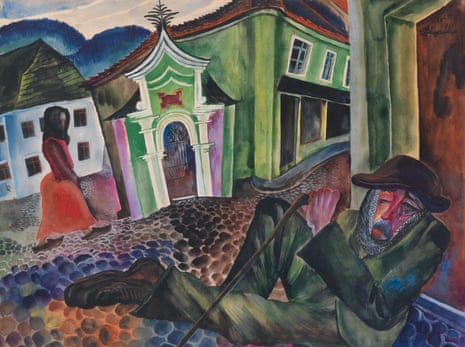

Grosz makes the same confusion of war and civilian life, sex and death, explicit in his 1916 painting Suicide. A prostitute holds up a flower at a window as a young man lies dead in the street. The city night is lit up in the red of sex and blood. The jagged cubistic composition sends everything spinning off in fragments. Reality has been blown apart and death has poisoned desire.

That mixing of Eros and Thanatos, sex and death, has shaped the image of decadence in art and literature, at least since Charles Baudelaire published his Les Fleurs du Mal poetry collection in 1857. The Weimar Republic – a fledgling German democracy established in 1919, only to be undermined by economic disaster and overrun by Hitler – has long been portrayed as decadent. Magic Realism does nothing to overturn the cabaret image – it even has a section called Cabaret. Yet the sensual, provocative art of Weimar’s jazz-filled nights is full of freedom and possibility as well as perversity and darkness.

The biggest discovery here is Jeanne Mammen. Her images of Weimar women are liberated and hedonistic. Two, with sleek short hair, lounge while smoking and daydreaming in her 1929 watercolour Boring Dolls; prostitutes are portrayed as defiant working women in her 1930 piece Free Room.

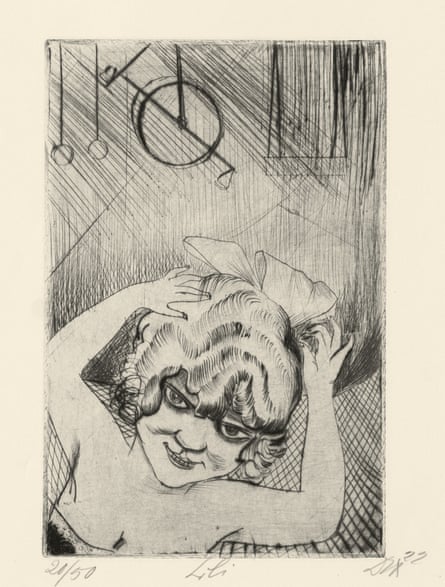

The curators see her imagery as a riposte to the male artists in the show but, to me, she has much in common with Dix. In Circus, his series of etchings, gender fluidity abounds in a fantastic playground of sexual experiment. The lion-tamer is part man, part woman and part beast. She holds up a whip that seems aimed at the viewer of the image as much as any circus animal. Sailors and sex workers, acrobats and musicians populate this fascinating, fleshy art.

“Magic realism” was coined by a Weimar critic to describe these rich and strange fusions of the real and fantastic. It is a good term to revive because for too long art history has tended to crush this raw genre with cold, technical language.

This is the kind of display Tate Modern’s collections need – a truly revelatory voyage through art and history. It is a past that feels like our present, and the art here holds up a mad mirror to a mad world. It is degenerate with a vengeance.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion