There are many strange things in the strange world of the early-20th-century Irish artist Harry Clarke, but the strangest is that his work is hardly known in Britain. Perhaps we just don’t trust it. Clarke’s highly stylised iconography, much of it created for Catholic churches, depicts an eerie, if not erotic, panoply of pale saints who look as though they have wandered out of an Aubrey Beardsley print and into a Hammer horror. This binding of the bizarre and the faithful is almost too much to take – until you cross the Irish Sea.

Only when I made my first visit to Ireland recently were my eyes opened to Clarke’s work. Visiting Cork, I met Ann Wilson, an art historian, Clarke aficionado and a contributor to the lavish new book Harry Clarke and Artistic Visions of the New Irish State. She took me to the Honan Chapel, designed in 1916 and part of University College Cork. I was shocked. It was less a place of worship than a spaceship pulsating with an alien vision. It hummed with an eerie power – even the floor was a zodiac mosaic. It didn’t seem very holy to me. Rather, it felt like the product of an aesthetic that dragged the decadence of Wilde and Beardsley, via Gustav Klimt’s enamelled strangeness, into the stridency of art deco, only to end up somewhere else entirely, far into a faithless future or deep in the pagan past.

As Wilson notes in her essay on the chapel in the new book, Clarke was drawing on Celtic and pre-Christian images. From a distance, the windows seem like standard Victorian stained glass; up close, you see how outlandish they are. Gobnait – patron saint of bees – is depicted with a “pointed, impassive profile”, as Wilson writes, her “unnaturally long slim hands and geometrically stylised body” giving her “an otherworldly, non-human appearance”. She is more construction than saint. Elsewhere, Judas is seen chained to an island for his sins, a fearful, claw-footed, semi-rotten thing.

Little of this has anything to do with the typically consoling imagery of modern Christianity. That’s why I liked it. As a Catholic of Irish ancestry, I was already prey to such perfervid mysticism. But then I discovered I’d actually known Clarke’s work since I was a boy: the stained-glass panels in our parish church – giant floating images of the Sacred Heart and the Virgin Mary – were made by his studio. These luminescent icons, which I saw through closed fingers and the blue smoke of incense, trembling from my grey-short-clad knees, hypnotised by their big eyes and oddly folded robes, as if made from origami, were burned on my memory. This was a sensate influence – and they suddenly became clear in Ireland, where faith was not remote or rational but tangible and mystical, where blessed virgins stand on street corners venerated by battery-powered candles and holy wells pour out of ancient pagan sites overlooked by graffittied statues.

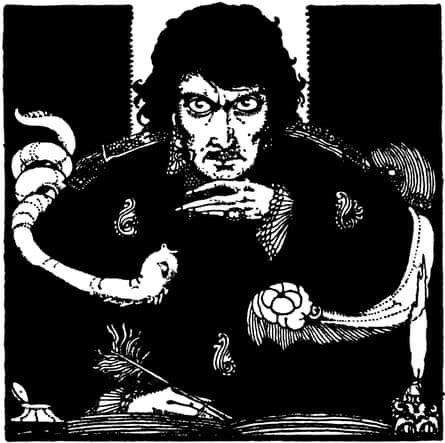

In Cork’s Crawford Art Gallery, Wilson surprised me again by introducing me to Clarke’s decidedly secular watercolours. They were astonishing: spinning wildly from their subject matter – Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination and the fairytales of Hans Christian Andersen (two writer-fantasists who create their own queer worlds) – into science fiction. Impossibly attenuated queens in lapidary baroque gowns entwine themselves in writhing tentacular phalluses that end in staring eyeballs. Dead souls, robed in red, rise through amniotic seas like seaweedy embryos. More HR Giger’s Alien than Arthur Rackham, these fantasies swirl in an inky profound full of shapeshifters: humans slip into selkies or mutate into chimeras, spouting fins, spikes and wings.

Little wonder that the Irish writer George Russell (“AE”), declared Clarke to be “one of the strangest geniuses of his time” who “might have incarnated here from the dark side of the moon”. Or that WB Yeats called him “Ireland’s greatest artist in stained glass”. They sought to co-opt Clarke into their seductive Celtic Twilight culture revival, but his work defied categorisation. Like David Jones, another artist of Clarke’s time who drew on Celtic myth (Welsh in Jones’s case), Clarke melded the brutality of the 20th century with extreme, if not obsessive, fantasy.

Jones, a Catholic convert, was a first world war veteran who suffered from chronic shellshock. Clarke’s body would be compromised by tuberculosis and the toxic chemicals he used in his art. Both men were drawn to the crucifixion and the notion of sacrifice. Jones portrayed himself as a semi-naked soldier, the stigmata blending on his body with his trench scars; Clarke posed similarly stripped for his own crucifixion images in astonishing photographs that evoke the terrible vacuum of a Francis Bacon canvas. It’s as if his body were echoing the psychic trauma of famine, revolution and war – as well as auguring the wasting disease that would kill him.

Clarke was born in Dublin on St Patrick’s Day, 1889, and was educated at the same Jesuit school as James Joyce. His family worried that this influence led to Clarke’s “fascination with the terrors of damnation”. Having trained as an artist in Dublin and London, he returned to Ireland to work for the family firm, designing stained glass, illustrating books and advertisements. But his overreaching imagination soon disdained any sense of restraint.

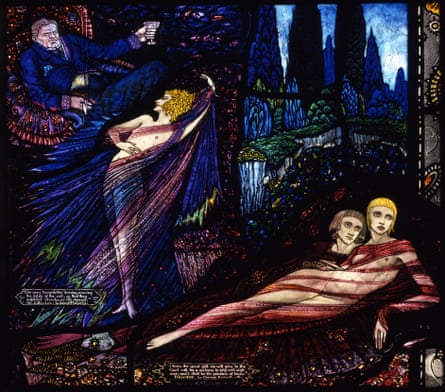

His images remain startling, even now; how much more so given the repressive culture in which they were born. One window design, The Others, part of a series commissioned by the Irish government in 1927 as a gift to the League of Nations in Geneva, shows why it would never be installed. A fey-looking woman in an astral-spattered purple gown holds her hand, quite nonchalantly, over the genitals of an androgynous figure who is naked from chest to thigh – a he-she reminiscent of a fetishistic Weimar cabaret artist, complete with stockings, slathered hair and grave-pale face. In another image, a languid female with a blond helmet bob stretches out her pallid body, veiled in diaphanous crimson. Her dead-eyed look would easily find a place in a contemporary avant-garde fashion spread. “It would give grave offence to our people,” declared the first president of the Irish Free State, William T Cosgrave. The project was aborted.

Clarke resembled his own pictures, with his slick heavy fringe and his huge dark eyes that looked as though he’d dropped deadly nightshade in them. He had an innocently narcotic look, more animal than human. He spent six summers, often with his friend, the artist Austin Molloy, on Inisheer, a remote island off the west coast of Ireland, where he dressed in a white felt báinín suit made from the wool of local sheep and wore peculiar red raw-hide shoes called pampooties. He might have been a faun in a design for Diaghilev by Léon Bakst.

Held out into the Atlantic, the sea came to obsess Clarke. Its creatures slid into his work. In Dingle, on the Irish west coast, I visited the convent chapel in whose windows Christ lays down his languid head on a coral reef encrusted with symbolist flowers. What the resident nuns made of such scenes goes unrecorded. For another commission, based on Keats’s The Eve of St Agnes, Clarke created half-circle fan lights entwined with tentacles, barnacles and seaweed. His medium was itself aquatic: his stained and etched glass was made from sand and kelp; an almost alchemical, fugitive process, given that glass is only a frozen liquid anyway. When researching Clarke’s work for my book, RisingTideFallingStar, I discovered that he’d drawn his marine images from intricate 19th-century glass models made by Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, which he’d seen in Dublin’s Natural History Museum. These accurate confections of jellyfish already looked like Tiffany lampshades; Clarke turned them into spectral brides drifting in gelatinous crinolines.

The new book reclaims Clarke as a modern artist. It sets him at the heart of the nascent Irish Free State, negotiating the secular and the sacred at a time when the twin powers of state and church collided and colluded. The authors observe that it was “a degrading and dark era in Irish history” whose abuses are still emerging. Yet within that darkness, Clarke’s work glows. “Ethereal and beautiful and, in its wit and contemporaneity, strangely compassionate”, his art reflects an Irish society “much more cosmopolitan, sophisticated and aesthetically aware than has normally been acknowledged”.

For me, there’s one thing missing in this beautifully produced volume; the wide-reaching essays – which show how Clarke’s stained glass even ended up in remote African villages – do not extend to the issues of gender raised by his work. Clarke married Margaret Crilley, a fellow artist, in 1914, and they had three children. Yet the queerness in his work seems startlingly explicit, hiding in plain sight: in convents and chapels, in popular publications and in his dandified performance. Given the fate meted out to Oscar Wilde, his fellow countryman, Clarke might have hesitated to transgress too far. But it could hardly be possible to make a more public statement than he did. His gloriously strange vision still bursts triumphantly through those leaded windows.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion