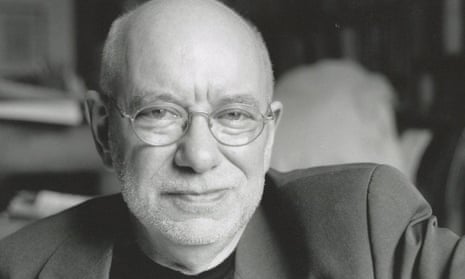

When asked what he wrote about, my father, the author Clive Sinclair, who has died aged 70 after suffering from cancer, always had the same reply: “Sex, death and Jews.”

His novels include Blood Libels (1985), Cosmetic Effects (1989) and Meet the Wife (2002), but the short story was his true home. The tales in his first collection, Hearts of Gold (1979), for which he won the Somerset Maugham award, as well as later collections, Bed Bugs (1982), The Lady With the Laptop and Other Stories (1996) and Death and Texas (2014), traverse the globe, from north London to Cuzco, Cairo, Stockholm, Mexico City and beyond. But the two abiding imaginative frontiers to which he always returned were the US, in particular the wild west – and Israel, to him the wild Middle East.

He was born in London. His education began with daily trips to the Mill Hill library with his mother, Betty (nee Jacobovitch), a housewife turned artist. Equally formative were his weekly trips to the Hendon Odeon with his father, David Sinclair (a partner at Simbros Furniture factory in the East End), and little brother, Stewart, with both boys dressed in their stetsons and six-guns. Thus began his lifelong search for his “inner cowboy”, which took him – with the help of a British Council fellowship – to the University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1979, and came to fruition in Clive Sinclair’s True Tales of the Wild West (2008), a blend of fact, fantasy and fiction that he called “dodgy realism”.

The sardonic humour that categorised much of his work was forged at Orange Hill County grammar school for boys, then the University of East Anglia, where he took a degree in English and American studies, and which he left (in his own words) “fit for nothing but writing”. At 21 he wrote a novel, Bibliosexuality, published in 1973, but it was with Hearts of Gold that his career took off. The collection received glowing comparisons to Kafka, Borges, Nabokov and Singer, and in 1983 Clive was chosen as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists alongside Kazuo Ishiguro, Ian McEwan and Graham Swift.

Life became stranger than fiction in the mid-90s, a time that he chronicled in his book of essays A Soap Opera from Hell (1998), with the loss of his parents, the failure of his kidneys, and the death, aged 46, of his wife, Fran (nee Redhouse), a special needs teacher, whom he had met at UEA and married in 1979.

While he often likened himself to the “Bulgarian optimist” – when prompted that “things can’t get any worse”, he would reply, “oh yes, they can!” – the truth is that he was lucky in love, twice. He spent the last 20 years of his life with Haidee Becker, an artist.

He will be remembered by his friends, family and readers as Hendon’s answer to John Wayne. His final collection of stories, Shylock Must Die, will be published in July by Halban.

He is survived by Haidee, me, and his stepchildren, Jacob and Rachel.