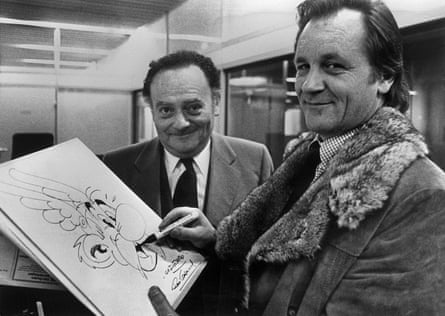

On the balcony of a flat in Bobigny, near Paris, one afternoon in 1959, two men – the writer René Goscinny and the artist Albert Uderzo – were desperately seeking an idea for a comic strip. It had to be original, it had to be inspired by French culture and it had to be finished within three months, to go into the launch issue of a new magazine. Browsing through the history of France they settled on an idea that seemed full of possibilities: the history of the Gauls.

From their school days they recalled the name Vercingetorix and decided their chief characters’ names should also end in “ix”. Roman names would end in “us” and town names in “um”. That Eureka moment gave birth to Asterix the Gaul and a series of 38 books that have sold 377m copies in 111 languages, and have inspired 10 animated and four live-action films, a theme park and more than 100 licensed products.

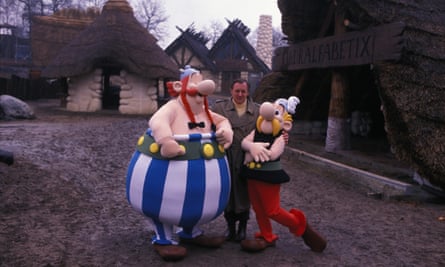

Bringing the little Gaul to life was the task of Uderzo, who has died aged 92 from a heart attack. With his most famous creations, he reversed the usual comic-strip pairing of a large, handsome hero and his small comical sidekick. The diminutive Asterix, with his bulbous nose, formidable moustache and winged hat, lived in a small village in Armorica (Brittany), the last holdout against the Roman invaders who surround the area. Asterix and his inseparable pal, the oversized Obelix, empowered by a magic potion brewed by the druid Getafix, endlessly trounce patrolling soldiers, hunt wild boar without weapons and travel to distant lands.

Uderzo instilled great energy in his characters, whether it was an exaggerated haymaker launched by Asterix lifting a legionary into the air, or the impossibly blurred legs of someone running, onlookers flung aside like bowling pins as they race past.

The books entertained children and adults alike. Goscinny’s scripts used multilayered jokes and running gags throughout, poking fun at every cliche conceivable, while Uderzo’s detailed frames referenced literature from Don Quixote to Zorro and movies from Fellini’s Satyricon to James Bond. A panel might contain a caricatured cameo of Jacques Chirac, Laurel and Hardy, or the Beatles, or hint at a famous piece of art – Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson, perhaps, or Rodin’s The Thinker – in the poses of his characters.

Sales of albums reprinting the weekly Asterix stories began slowly: Astérix le Gaulois (Asterix the Gaul, 1961) had an initial print run of 6,000; the second, La Serpe D’Or (Asterix and the Golden Sickle, 1962), 20,000; the third, Astérix et les Goths (Asterix and the Goths, 1963), 40,000. By the 10th book, Astérix Légionnaire (Asterix the Legionary, 1967), the first print run was a million copies. This was doubled for La Rose et le Glaive (Asterix and the Secret Weapon, 1991).

Uderzo was the fourth child of Iria (nee Crestini) and Silvio Uderzo, Italians who had moved in 1923 from La Spezia, Liguria, to France, seeking work for Silvio, a carpenter. Albert was born in Fismes in north-eastern France, and was registered as Alberto – his father accidentally pronouncing Albert in its Italian form to the registrar. He grew up in Clichy-sous-Bois, a suburb of Paris, and the family became French citizens in 1934.

Albert followed the adventures of Mickey Mouse in the pages of Le Petit Parisien newspaper and, from 1934, in Le Journal de Mickey. He struggled at school, showing promise only in art. Encouraged by his mother and his older brother, Bruno, he sketched in pencil and, around the age of 12, began painting – which revealed for the first time that he was colour-blind.

When the second world war began, Bruno joined an army regiment at Clermont-Ferrand, but the lightning advance of German occupying forces meant his unit was disbanded and he was placed in a youth camp by the Vichy government. Albert and his family were often hungry under occupation, but he graduated from school and hoped to become a car mechanic.

Bruno, released in 1941, returned home. Slowly recovering, he noticed his brother’s continued efforts at drawing comics, and submitted some of Albert’s drawings to Société Parisienne d’Édition (SPÉ), which published popular children’s magazines and comics. Albert was offered a summer job. Encouraged and advised by editors, designers, and the artist Edmond-François Calvo, he produced illustrations, debuting in Boum, the supplement of the magazine Junior, with a parody of Jean de la Fontaine’s fable The Crow and the Fox.

Bruno, working as a mechanic in Brittany, suggested Albert should join him. He got a job on a farm and learned to love the wild coasts and cuisine of what he called a “magical region”. When, later, Goscinny left the decision of where to set the Asterix series to Uderzo, he chose Brittany.

After the Liberation, Uderzo joined the small Paris animation studio of Renan de Vela as an inbetweener, drawing frames that produced smooth movement, on the 11-minute black-and-white animated film Carbur et Clic-Clac (1946). Through the studio he created his first comic book, featuring the medieval swordsman Flamberge Gentilhomme Gascon (1945). After a few months, Uderzo spotted a competition advertised in France Soir, and submitted sketches of a character named Clopinard, a Napoleonic soldier with a spring-loaded wooden leg. He won, and Éditions du Chêne commissioned a story, published as Les Aventures de Clopinard (1946).

For the newly launched magazine OK, he created Arys Buck (1946-47), a tall, blond prince with a magic sword, who was accompanied by Cascagnasse, a small, moustached sidekick in a winged helmet. The theme of a strong leader and a small, clumsy sidekick was further developed in Prince Rollin (1947) and Belloy l’Invulnérable (1948-49).

Uderzo’s career was briefly interrupted by military service, after which he began working for France Dimanche, illustrating news stories, advertising, and brief true-crime and true-romance strips, where his talents for realistic drawing developed. In this style, he drew Superatomic “Z” (1950) for 34 Aventures magazine and Capitaine Marvel Jr (1950) for the Belgian comic Bravo! (Le Soir).

Visiting Brussels, Uderzo took on work for Yvan Chéron’s International Press agency, which shared an office with another agency, World’s Press. He was introduced to Goscinny there in 1951. Uderzo began illustrating two columns written by Goscinny – Qui a Raison? (Who’s Right?) and Sa Majesté Mon Mari (His Majesty My Husband) – for the women’s magazine Les Bonnes Soirées.

They continued their collaboration through the pages of La Libre Belgique, creating the sailing adventure Jehan Pistolet (1952-56), the light-hearted Luc Junior (1954-57), about a Tintin-esque investigative reporter and his dog, Alphonse, and Bill Blanchart (1954-55), about a big-game hunter.

Uderzo and Goscinny produced the gag cartoon Monsieur et Madame Plume (1958) for Paris Flirt, but their most significant work appeared in Tintin magazine, where they created Poussin et Poussif (1957-58), about a young boy and his dog, and Oumpah-Pah (1958-62), the comic adventures of a Native American and his friend, a French military officer named Hubert. Then, in 1959, the new magazine Pilote featured their Astérix le Gaulois in its debut issue.

After Goscinny’s death in 1977, Uderzo completed the work his partner had started on Astérix Chez Les Belges (Asterix in Belgium, 1979), then continued the series as both writer and artist, starting with Le Grand Fossé (Asterix and the Great Divide, 1980). Uderzo’s subsequent albums – nine in all – were of variable narrative quality, lacking the complexity and subtlety of the earlier books. The last, Le Ciel Lui Tombe Sur la Tête (Asterix and the Falling Sky, 2005), introduced a science-fiction element and was widely panned.

Uderzo had split from Dargaud, the publishers of Asterix, wresting rights to the books from them following a 1998 court case, and established Les Éditions Albert-René to publish his new Asterix stories. He sold a 60% stake in Albert-René to Hachette in 2009, and decided to retire two years later. The first Asterix album from a new creative team of Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad, Asterix and the Picts, was published in 2013.

Uderzo came out of retirement briefly following the terrorist attack at the office of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015. His two illustrations – Asterix punching a terrorist out of his sandals and a more sombre image of Asterix and Obelix with their heads bowed – were published in Le Figaro.

He is survived by his wife, Ada (nee Milani), whom he married in 1953, and their daughter, Sylvie.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion