Ugliness is not always repulsive. A casual survey of the history of art shows that what’s thought repulsive in one generation is often accommodated into a concept of the beautiful in the next. In the middle ages, the Alps were an ugly prospect of horror. Now they are a holiday resort where people gasp at their natural beauty.

Nor is ugliness any impediment to personal success. Beauty is boring – but ugliness, no matter how difficult to define, always fascinates. Put it this way: if everything were beautiful, nothing would be. Our word ugly derives from the Old Norse ugga, which means aggressive. We need a measure of visual aggression to make beauty comprehensible, even tolerable.

Sometimes people aspire to ugliness, as the hilarious results of Zimbabwe’s Mr Ugly showed: the delighted winner, grinning from ear to ear, was this week criticised for not being ugly enough. Similarly, California’s immensely popular Ugly Dog Competition often declares winners who are immensely cute.

When the designers were working on the jacket of my book Ugly: the Aesthetics of Everything, someone suggested adding a question mark and giving the whole cover a mirror finish. Curious browsers would be immediately confronted with their own image and a deadly question: how beautiful are you?

The coordinates of attraction and repulsion are always shifting. We all enjoy beauty. Or say we do. But an appreciation of ugliness is necessary to it. The beautiful and the ugly are not opposites, but aspects of the same thing. Concerned what people think about your house? Wish your partner were better-looking? In dieting, getting a tan or going to the gym, choosing a Weimaraner over a rescue mutt, visiting an exhibition or shopping at Westfield, we are trying to acquire beauty to give us a personal competitive advantage. But don’t worry if you feel ugly: perceptions change.

In 1969, a group of London advertising folk, fatigued with the conventions of their trade, started The Ugly Modelling Agency. They wanted faces with character, not bland perfection. Look at the photographs from the time and you wonder what the fuss was about. The agency survives as Ugly Models, and has Diesel and Calvin Klein as clients.

Meanwhile, ever since the Francophile Nancy Mitford popularised the expression, we have had the idea of jolie-laide, a woman who can be attractive and ugly at the same time. Mitford was herself an example. So too is Jeanne Moreau. “Beauty” is not necessarily attractive. Nature is not a reliable source of beauty and can be rather nasty. Not all plants conform to beautiful conventions: the Amorphophallus titanum is a hideous, swollen phallic thing stinking of death: it is known as the corpse flower.

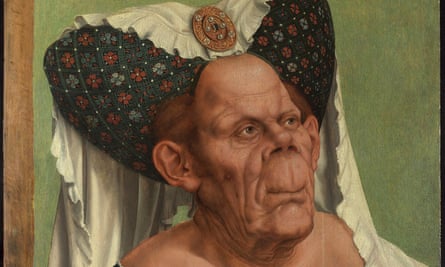

But ugliness is not always repulsive. One of the most popular pictures in the National Gallery is Quentin Matsys’s The Ugly Duchess (which inspired John Tenniel, the illustrator of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland). Besides, tastes change. The tides of taste go back and forth, erasing aesthetic certainties. This is a truth so disturbing that most of our assumptions about art are immediately and ruinously undermined.

For instance, two years before it was finished, the great Paris “intellos” of the day lined up in opposition to the Eiffel Tower, writing letters to the papers denouncing it as an ugly and hateful column of bolted tin. Of course, it is now one of the world’s most beloved monuments.

John Ruskin, the Victorian booster of nature’s beauty, campaigned manically against the ugly intrusion of the steam railway into the unspoilt and tranquil Lake District. And he despised the introduction of the noisy vaporetto into the dignified Venice he regarded as his private intellectual playpen. Now we see each machine as quaint and lovely, possibly even beautiful. Back in Ruskin’s London, the Albert Memorial, now a national architectural treasure as fondly regarded as hot buttered toast and the shipping forecast, was once described as verminous and crawling.

Darwin explained our need for “beauty” in saying that breeding attractive children is a survival characteristic: I may feel the need to fuse my premium genetic material with yours so that humanity continues in the same fine style. But there may be a mathematical, as well as biological, basis to the conventional ideas of the beautiful. The Greeks believed beauty can be described by numbers. Classical sculpture was based on strict ratios and classical architecture is pleasing because its proportions are based on the eye’s field of vision.

Besides measurement, another factor that changes our perceptions is time. “Familiarity is a magician that is cruel to beauty, but kind to ugliness,” according to the excitable Victorian novelist Marie Louise Ramé. This might not be as mad as it first sounds. It’s beauty that is evanescent and fragile. When something becomes familiar we tolerate it, and tolerance can grow into affection. And, as that grizzled old gargoyle Serge Gainsbourg remarked: “Ugliness is superior to beauty because it lasts longer.” Maybe a thing of ugliness is a joy forever.