As promised, the Green Man stands adjacent to Edgware Road tube station. He gazes out over one of London’s more architecturally challenged districts, an oasis of anonymity and calm amidst the homeward-bound bustle. Yet we do not accept his offer of hospitality. It is the wrong Green Man.

A quarter of a mile from the pub is the photographer’s studio. Inside, a different Green Man offers to make us coffee. This one’s a little more familiar, though he wears his hair longer these days. Even with the benefit of a pair of medium-heeled loafers he is as petite as legend maintains. It’s OK, we’ll make our own coffee. None for him – but thanks for asking.

Could this be the one? The emerald eyes seal the issue.

“There’s water too,” he points out in lugubrious Mancunian. “Still or fizzeh!”

We have coffee. He goes without. Caffeine-free, non-carbonated, swaddled in autumnal beiges and browns and generally looking more lovely and more temperate than both summer’s lease and the average bush baby combined, he is the Green Man. The right Green Man. For today’s purposes, our Green Man.

“This is a bit of a turn-up, eh? The NME!”

Indeed.

“I heard you wanted to do us in Take That.”

Very much so.

“I think we were always a little bit nervous. Like, ‘Oh aye…!’ When I was younger I always saw it as an indie magazine. You know, you had to be in a band with guitars to get in there.”

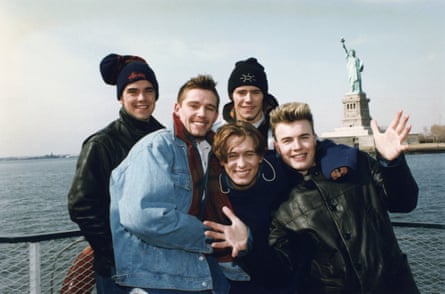

Mark Owen – for it is he – jiggles his facial muscles and smiles the smile of a man in a band with guitars in NME. Coincidentally, it is also the smile with which he became officially the most popular member of Take That and, therefore, the epicentre of a great many young women’s thoughts, waking and otherwise. These days, however, Mark Owen is no longer obliged to brandish that smile like his meal ticket to the world. As he says, it is a bit of a turn-up.

“When I looked in the mirror I didn’t just see a cute guy. I always thought of myself as being quite creative, just a person who was trying to learn a little about life.”

Mark Owen is unique among his former colleagues in the premier-selling pop act of the 90s, for only he has been able to leave behind that which made him a member of Take That. Robbie Williams did the decent thing and quit but, contrary to the lyrical thrust of his solitary solo hit, could not find freedom from his bad-boy persona. Gary Barlow’s mission to become the authentic hellspawn of Elton John and George Michael has continued with terrifyingly clinical precision, hence the protracted non-appearance of his debut album. Howard and Jason, meanwhile, remain missing, presumed inactive.

But Mark – “the cute one”, recipient of two-thirds of Take That fan mail, reputedly quite certifiably “nice” – has gone and made an indie rock album. Well, a sort of indie rock album, the sort of indie rock album that will delight occasional devotees of Crowded House and those who think Radiohead sound heavy metal. It’s called Green Man, he did it with proper producers (John Leckie and Craig Leon) and proper musicians (Blondie’s Clem Burke, XTC’s Dave Gregory), and, most incredibly, wrote it all himself. Within four months of the split, the man whose creative input to Take That amounted to fragments of a couple of B-sides had penned 31 songs about life as Mark Owen – eco-friendly spirit and real person, and was recording at Abbey Road with the men responsible for all the technical gubbins behind the debuts of The Stone Roses and The Ramones.

Excuse me, you are the Mark Owen who came out of Take That, aren’t you? Our little Green Man gives it that smile.

“The easiest option for Mark Owen who came out of Take That was to get some other people to write some nice catchy pop tunes, and maybe I could have done that for a couple of years. Then I probably would have been hated by everybody and fell by the wayside. But there wouldn’t have been an album unless I’d written it and it had come from me and I felt like it was my album. That’s all I was interested in.”

Once his record company had agreed to give Mark’s crazy idea a go, he set about severing the ties with his past. He moved out of his flat in Rochdale and bought a big ramshackle house in Cumbria. He relinquished the services of Nigel Martin-Smith, the manager who had assembled Take That and oversaw their irresistible ascent to prefab infamy. And he decided that his album should sound like it had been made by a band, as opposed to a computer.

Had Mark gone about matters differently it’s safe to assume that his album would have sold considerably better than it has. Popping up on one of the many kiddie TV shows who faithfully welcomed the new Mark Owen back to the fold, he claimed, to goggle-eyed disbelief, that he didn’t care whether it went to No 1 in the charts or No 101. Disappointingly, it did neither: Green Man vaulted like a gammy-legged former teen idol to No 33, then limped apologetically away (though it has, the record company press release helpfully points out, been doing very well in Spain).

Raise this matter and Mark betrays the DIY zen thought processes of a young man who was enlightened to the joys of meditation by Lulu.

“You can’t really dictate to people, you can’t put money in their hands and say, ‘Do this’. So I made the album for me. Sales-wise now, it’s different from Take That, obviously. I… I admit I was surprised at that. It’s been slow and I’ve had to make an adjustment, ’cos I was so used to being in a band where every song they put out went to No 1 and sold a million copies. I might have been thinking it’ll start from where Take That left off, but it hasn’t worked out that way. I’m pleased about that now. I want to sell records because they’re good enough. I feel that’s a very comfortable position to be in.”

Not that anyone expects anything from the man whose musical role in Take That was, as he cheerfully confesses, “virtually zero”. Of course the same logically applies to the other ex-three-fifths of Take That not called Gary Barlow. The most remarkable aspect of the Robbie Williams saga was how merely by occupying the same immediate airspace as Oasis he was suddenly taken seriously by the music business. His gambit of covering a George Michael song was acceptable only on the grounds that it was potentially a dig at Barlow, but once Rob joined his old mate on the pie-plan diet the joke rapidly wore, erm, thin.

Owen, however, has long been the recipient of that wearisome brand of condescension heaped upon the pretty, predicated by the assumption that they must be vacant. Mark, so we heard, was a bit dim, the patsy with the angel face, a willing agent of the puppet-master’s strings. To the latter charge, at least, he pleads guilty.

“I do feel I had the wool pulled over my eyes, but I did it to myself. I just sat inside Take That with my four mates and I was very happy and I didn’t give a damn about what was going on outside. I would never have left Take That. I would have stayed in Take That as long as Take That was going. I might not have had the nerve to do what Robbie did, but I never had the reason to leave. And even if I’d had the reason, I might not have had the nerve to say, ‘I’m leaving’. It felt like I was doing a job, and in my life everything that I’ve done, I’ve always tried to do to the best of my ability. I wasn’t the main spokesperson. Gary led the pack. If things bothered me, I would put my opinions across, but I’d put them across nervously. I was this whisper in the background.”

How comfortable were you with your role in the band, being perceived purely in terms of how you look?

“Do you know?” he says, eyebrows raised. “Maybe it should have bothered me. But it never did, because I knew there was a bit more, and if that’s how people wanted to see me I was happy with that.”

People also wanted to see you as gay.

“It didn’t bother me. Because, well, we weren’t. None of us cared anyway, we started off in the gay clubs, we’ve got no problem there. We thought the mystery was good, that’s what got us in the papers. The press helped us at the start, it helped build a fan base. But when you’re in the papers all the time, if you do fall down that’s documented as well. And that’s something that’s very hard to deal with.”

Mark Owen believes Brian Harvey’s enthusiastic espousal of the educational possibilities of MDMA was “very sad and very stupid”. He states that he’s never had to take drugs in order to enjoy himself. He suggests that, in this respect, maybe he’s “lucky”.

And Brian Harvey, presumably, one of the unlucky ones.

“Maybe at the time he’d said it, he’d just taken the 12 Es the night before.”

Mark Owen laughs. In over an hour’s conversation, it’s the closest he offers to a comment at someone else’s expense. Assuming we do not consider “damn” an expletive, he swears a paltry three times – one fuck, two shits – and half-whispers when so doing. Despite admitting to feelings of disappointment that Take That bowed out with a cover version, he baulks at the suggestion that Gary Barlow may have been holding back his own songs for that long-predicted solo career. “Gary didn’t ever want to hurt anybody else,” he says, forehead creased with sincerity. “We were very close.”

Mock him if you choose. And if you do, isn’t part of the reason the fact that Mark Owen, the boy who’s always tried to do everything to the best of his ability and who therefore stuck out Take That as one would a challenging new position at work, is just that little bit too much of a decent human being to succeed as a credible pop icon?

In a recent Sunday supplement article about famous people’s neighbours, the couple next door to Gary Barlow implied that the songwriter formerly with Take That was a bit of a knob. Big house, big fence, big ego – and don’t even think about asking for a cup of sugar. You suspect that whoever lives down the Lake District lane from Mark Owen has it a little less exciting, but a lot… well, nicer.

Although there would be no point asking him for sugar, either. The Green Man takes it without.

© Keith Cameron, 1997

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion