The first inhabited place on Earth to ring in the year 2000 was probably the Pacific island nation of Kiribati. As dancers on the beaches welcomed the dawn of the millennium, on the other side of the planet, in Greenwich, final preparations were underway for the opening ceremony of the Millennium Dome. This was the night when the first 10,000 specially invited people would finally see what was inside the big white tent in south-east London that had been the subject of intense speculation and scrutiny for the previous four years. It had to be perfect.

By 7pm in Greenwich, it was apparent that there was a problem. In the weeks before the event, because of a logistical cock-up, hundreds of guests had not received their tickets through the post. Ticketless guests had been instructed to pick them up on New Year’s Eve at Stratford station, before hopping on the newly completed Jubilee line to the Dome for the festivities. But on the night, body scanners installed by police at Stratford weren’t working, and before long, several hundred people were stuck in the station. When the prime minister, Tony Blair, arrived two hours later – while fireworks illuminated more than 1 million people gathered in Moscow’s Red Square – angry invitees, including many of the UK’s newspaper editors, were still no closer to boarding a train to Greenwich.

There was more trouble to come. At 10pm GMT, as Nelson Mandela marked the new year by lighting a single candle in his old prison cell on Robben Island, Jennie Page, the chief executive of the Dome company, had just received some further unwelcome news. Rushing to witness the Queen receiving the Millennium medal, a specially commissioned honour to mark the occasion, Page was stopped and, in her words, “told about the bomb”. The police had received a call to inform them that there was an explosive device in the Blackwall tunnel, which ran beneath the Dome. Blair and the Queen were also informed.

About 15 minutes later, Peter Higgins, designer of one of the Dome’s 14 “zones”, was giving a tour to Blair, his wife Cherie and their children. “I just thought: this guy’s not listening,” recalled Higgins. “He was ashen-faced, and holding his family.” During the tour, Blair, as well as the police and Page, had to decide whether or not to cancel the country’s millennium celebration, the culmination of many years’ work and £750m of investment. “It was a decision one would have preferred not to have to take,” Page said, gravely.

They carried on. The call turned out to be a hoax, there was no explosion, and the stranded guests at Stratford did eventually make it to the Dome for the countdown, despite having missed the festivities beforehand. After four years of politicians and press forecasting the project’s failure, by the time midnight reached Greenwich, just as 39 tonnes of fireworks were forming a “river of fire” down a four-mile stretch of the Thames in central London, it seemed as if the people behind the Dome had pulled it off.

The next morning, the headlines told a different story. “The Black Hole of Stratford East” read one. “The £758m disaster zone” read another. Michael Heseltine, who sat on the Millennium Commission, which had brought the Dome to life, blames the standstill at Stratford. “It was a PR disaster,” he told me recently. “A lot of the people who didn’t get there on time were the very people who were going to report the event.”

But for the thousands of people involved in putting on the Millennium Experience, from government ministers to service staff, the worst was yet to come. For the duration of the year that the Dome was open, it was perceived as a catastrophe. Richard Rogers, one of the architects behind the building, said in 2015 that it “couldn’t have had a worse reception if you’d worked hard to deliberately upset everybody”. Twenty years later, it is still a byword for New Labour hubris, squandered resources and hideously bungled planning.

In fact, it was a byword for all of these things before it even opened. The urge to think of the Dome as something pitiable was apparent long before anybody actually saw what was inside. In the final paragraph of Elizabeth Wilhide’s official book on the Millennium Dome, published in 1999, she writes that “its legacy, the Dome’s true meaning, will only be known long after the moment has passed, when the children who are its visitors today grow up and look back”. Now, doing just that, it is clear that the prevailing narrative that the Dome was a total failure is not – or at least not quite – the full story.

When we met recently, in a country pub near her home, Jennie Page spoke of her time on the Dome with the same dignified forbearance you sometimes see in military veterans. “There are a lot of things I will not talk about,” she told me. In 1995, she became head of the Millennium Commission, which had been established to distribute funds generated by the National Lottery. She now carried the daunting responsibility of deciding on a once-in-a-lifetime exhibition to mark the new millennium.

In February 1996, Greenwich was selected as the site for the Millennium Exhibition, not least because of the connection to Greenwich mean time, but it would be years before real progress was made in deciding what form the exhibition itself would take. At that point, the commission’s most urgent task was coming up with the structure, or structures, to house the exhibition. Mike Davies, who went on to become the lead architect on the Dome in April 1996, knew that once the site was chosen, construction would need to start as soon as possible. Four years is not very long for big projects. John McElgunn, a partner at Davies’s old firm Rogers Stirk Harbour, said: “It’s like asking somebody to hurry through their pregnancy in four months.”

The building would also need to solve the problem of the site’s exposure to the elements. “In March, we were on the site, and it was minus four,” Davies told me. Whatever else they did, the site was definitely going to need shelter. Standing there in the bitter wind on the peninsula, he had his eureka moment: “Let’s do a mega cover.”

Davies, who always dresses head to toe in red, is still clearly infatuated with the design of the Dome. For more than two hours, he spoke animatedly about it, showing me early drawings like a proud parent with an ultrasound picture. He was particularly enthused about the way the Dome embodied the concept of time. “Twelve months of the year, so 12 masts, 365 metres in diameter, and with 24 scallops, like 24 hours in a day,” he explained. The concept fit the bill perfectly, and was phenomenally cheap at £42m. When plans for the building were released in June 1996, though, not everybody was impressed. Wonderbra ran an ad campaign with the slogan “Not all domes lack public support”.

Over Christmas 1996, Page and her team settled on a budget for the whole Millennium Experience: £750m, pieced together from corporate sponsorship, National Lottery money and ticket revenue from 12 million visitors. But there was a potential iceberg on the horizon. Although there had been a Labour minister on the Millennium Commission, this was a Conservative government project, and Labour looked likely to win the general election in May 1997. If the new prime minister wasn’t on board, the whole project would be axed. But if the building was going to be finished in time for 1 January 2000, they had to keep going regardless. “That was a terrible period,” Page said briskly.

On 1 May, Labour won the election by a landslide, ending almost 20 years of Conservative rule. The mood of triumphant invulnerability in the Labour camp was one the Dome company could capitalise on. As media scrutiny of the project intensified, with the Sun running headlines like “Dump that Dome”, Page’s team put their plan to the government – a plan that emphasised New Labour-friendly aims. The Dome would, among other things, “raise the self-esteem of the individual” and “enhance the world’s view of the nation”.

Despite misgivings about the cost, the scale, and the London location for an event that was supposedly for the whole country, on 19 June 1997, Blair announced that Labour was on board. Here, perhaps, was a chance to make a physical monument to everything that New Labour Britain would be about: youthful exuberance, unashamed pleasure, looking with optimism to the future rather than clinging to tradition; a single amazing experience that could bring the country together. “New Labour really did think it was going to be some sort of quasi-political, sociological experience that would underpin everything that they were about,” the exhibition designer Peter Higgins told me incredulously.

Speaking to his party about possible celebrations for the millennium at the 1995 Labour conference, Blair had announced that there were now “a thousand days to prepare for a thousand years”. By mid-1997, time was already running out to get what was the largest construction project in Europe finished before the deadline to end all deadlines.

Now that the Dome had Labour’s stamp of approval, the organisers were faced with a pressing question: what was the Dome actually going to be? There were nine ideas for “zones” – body, mind, spirit, work, rest, play, local, national, global – but beyond that, not much. Only now, two years into the project, was serious thought devoted to the contents of this exhibition, already being billed by the government as “the biggest, most thrilling, most entertaining, most thought-provoking experience anywhere on the planet”.

Under the supervision of Peter Mandelson, the New Millennium Experience Company (NMEC), as the Dome company had been renamed, gave designers a brief that consisted mostly of open-ended questions. For the body zone, they included “Are we what we eat?” and “What about designer people?” Higgins, whose company, Land Design, ended up creating the Dome’s play zone, told me “the brief was very thin, and we weren’t given a budget at all”. For Blair’s part, he was on the lookout for content that had what he called “the Euan factor” – content cool enough that his 13-year-old son would want to see it.

In addition to the zones, a spectacular performance would take place in the Dome’s central space. An initial proposal from the theatre impresario Cameron Mackintosh, involving an enormous stage and a huge cast including children, was rejected by Page. “It involved 42 horses,” she told me, shaking her head. Instead, the rock show designer Mark Fisher took over. With singer-songwriter Peter Gabriel, he came up with a story inspired by Romeo and Juliet, which would be performed by more than 100 aerial gymnasts, who would be gathered from all over the country and trained for two years beforehand.

There were now 14 zones, each designed by a different company. In an attempt to try to give the visitor experience some kind of coherence, Stephen Bayley, a design consultant and critic who had worked with Terence Conran, was drafted in. Six months later, in December 1997, he parted ways with the Dome, after his proposals were deemed too highbrow. When we spoke last year, in his studios in Chelsea, Bayley lamented the “sub-Disney” plans for the zones. Higgins agreed that the project had needed a “master puppeteer”, but smiled wryly when Bayley came up in our conversation. “He was so the wrong person. He sat in one of our meetings just reading Proust in French on a sofa.”

Eventually, Page and her team came up with something they called the Litmus Group to oversee the content of the Dome, composed of cultural luminaries such as Alan Yentob and Michael Grade. Their suggestions were of varied quality, according to the zone designers. “God, the input was totally worthless,” said Higgins.

Meanwhile, Peter Mandelson visited Disneyworld Florida in search of inspiration. According to Adam Nicolson’s richly informative book on the Dome, Regeneration, Mandelson spent this trip breaking into a run to avoid being photographed in the same frame as Mickey Mouse. It was leapt on by the press, which ran headlines such as “Mandelson in a Disney about his Dome”. “It was so predictable,” Mandelson told me, “the press thought they were entitled to know everything, and anything that was held back, they’d punish you for it.”

By February 1998, the Dome’s contents were secure enough that prototypes of six of the zones – body, mind, spirit, rest, work and living island – were ready to be unveiled. The launch ceremony took place at the Royal Festival Hall on London’s South Bank, once the site of the Festival of Britain, the much-revered 1951 exhibition that served as inspiration to many of the Dome’s creators. “This is a chance to demonstrate that Britain will be a breeding ground for the most successful businesses of the 21st century,” Blair told the audience. Mandelson spoke, too, telling the room that “if the Millennium Dome is a success, it will never be forgotten. If it is a failure, we will never be forgiven.”

The launch did not go down well. Everybody found their own problem with it: it was too political, insufficiently historical, too populist, not populist enough. “The moment you have a big project in this country, the forces of darkness gather,” Heseltine grumbled to me. Davies remembers how strongly people felt: “I would go home in a taxi, and this vituperation would pour out about what a scandalous waste of money the Dome was.”

Since it was a government project, the government kept tight controls on what those involved could and could not say. Gez Sagar, an ex-Labour party press officer who was now doing press for the Dome, briefed everybody on what he called the line to take (LTT). It consisted of four central messages: “It’s the people’s show. It’s the most exciting experience of the millennium. It’s good for Britain. It’s going well.”

In June 1998, the final piece of the 10 hectares of fabric went up on the Dome’s roof, and the people involved in the project stood awe-struck beneath its complete canopy for the first time. The Dome is huge; weather systems would form inside it if it wasn’t for its Teflon roof, and the air it contains weighs more than the structure itself. “It just had this gorgeous sense of space when you walked into it,” Chris Smith, then the culture secretary, told me. Charles Falconer, who later took over from Mandelson as Labour’s Dome minister, recalled this feeling with evident pleasure: “I loved being inside it, I loved the whole physicality of the Dome. I absolutely loved it.”

Beneath the roof, however, all was not well. Political advisers, who referred to themselves as “content editors”, clashed with the zone designers, as they attempted to ensure it was New Labour-appropriate. If this was to be a flagship for Blair’s vision of Britain, it needed to send the right messages: the content had to be popular, pro-business, future-oriented and, above all, optimistic. “Keeping the politicians’ hands off it was a big struggle,” Page told me.

With more than 30,000 visitors expected every day in 2000, one thing the Dome would need was extensive catering. There were to be two enormous branches of McDonald’s, as well as a YO! Sushi and a cafe called Simply Internet. Twenty years on, Bayley still rues the catering. He proposed a farmer’s market; he got fast food. “You could have had sourdough bread and goat’s cheese,” he told me. “Instead the public had to eat filth from McDonald’s.”

Pleasing the sponsors, of which McDonald’s was one, was of paramount importance. Without sponsorship money of £12m per zone, the project was financially unviable. But what the zone designers wanted, what the politicians wanted and what the sponsors wanted were often incompatible. Higgins’ play zone was initially paired with Sky. “It was hopeless,” he told me. “They said to us, in a very aggressive way, the future of play is about digital television, because that’s what they were launching at the time.” Zaha Hadid’s mind zone was sponsored by the arms manufacturers Marconi and BAE systems.

One of the designer Tim Pyne’s four zones was work, previously titled Licensed to Skill, which was sponsored by the recruitment giant Manpower. He told me that his zone ended up reflecting the sponsor’s very particular idea of what an exhibit about the future of work should be: “No job security, zero-hours contracts and moving from job to job as an agency worker.” Pyne’s initial plans for the zone had involved visitors “getting sacked” at the beginning, but Labour party advisers instructed him to scrap the idea because it was thought a recession might be coming.

No zone saw more interference than the faith zone. The triangular, non-denominational design for the space, by Eva Jiřičná, was met with outcry from religious leaders all over the country, who were also worried that the commercialised environment of the Dome would make a mockery of religion itself. “Is Rupert Murdoch’s name going to appear on the manger at Bethlehem?” asked the Bishop of Woolwich. The government felt that the structure Jiřičná designed looked too much like a pyramid, which would evoke new-age spirituality rather than religion. Jiřičná’s solution was simple: “I put a plastic blob hat on it,” she told me. The hat did not pass muster, and the final design that the UK’s religious leaders agreed to was all but disavowed by Jiřičná by the end.

In October 1998, on the building site inside the Dome itself, the BBC held a televised debate about whether the Dome was going to be good or bad. All the participants wore hi-vis jackets and hard hats. While the children in the audience looked on nonplussed, the art critic Brian Sewell jabbed his finger at the Dome’s director of operations, Ken Robinson, and demanded repeatedly: “Tell us what is in it.” Robinson declined, and the rumour mill continued to turn. I remember that in the years before the opening, when I was about seven years old, my school playground in London was abuzz with talk of what might be inside. More than one person I know remembers hearing that there was going to be an anti-gravity chamber.

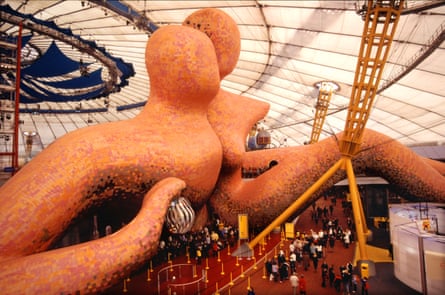

Six months before the grand opening, details of all 14 zones were finally made public. The money zone featured a tunnel made of £50 banknotes behind glass amounting to £1m, and an invitation to guests to “go on a million-pound spending spree” with virtual cash. At the “our town story” zone, schools from around the country were invited to put on performances about their local area. These were strictly limited to 20 minutes each. (Nicolson quotes Robert Warner, the head of the Dome’s live events, as saying at the time that they didn’t want “a three-hour opera about Grimsby”.) The body zone would allow visitors to walk through the inside of a human body, complete with moving organs and animatronic pubic lice.

During the final months of preparations, the Dome attracted yet more sceptical comment. JG Ballard wrote in the New Statesman that the building resembled “a sinister abattoir disguised as a circus tent”. According to Page, those months were “a frightful rush, and it was made much worse by the government changing the policy about ticketing, 10 months before we opened”. She whispered “10 months” again and shook her hands at the ceiling in disbelief. Falconer had decided to give away 1 million free tickets to schoolchildren, an idea that was not in the business model. “But the Dome was the property of the nation,” Falconer told me. “We wanted as many school children as possible to come.”

As the Dome finally began to take shape, the conceptual weakness of the experience was becoming increasingly clear. It was, after all, pretty difficult to deliver an “experience” for “the nation” – a grand day out that could, in some way or other, delight every single person in Britain, while staying within budget, keeping the sponsors happy, pleasing the press and embodying the government’s preferred vision for the future of the country. The Dome needed to be educational, but fun. Accessible yet challenging. Entertaining for children, stimulating for adults. It had to be “the greatest show on earth”, but also serve as an advertisement for sponsors like Boots the chemist.

As with any big project, the final weeks were chaotic. With just a few weeks to go until opening night, Tim Pyne was working on the world’s largest billboard – about as tall as a four storey house and as wide as a Boeing 747 – which would form the outside of the learn zone. It was a photograph of Richmond Park, which was being printed in a special facility in Iceland because of its enormous size. The printers called Pyne to ask whether the naked man in the woods, visible in the photograph at its full size, was a deliberate inclusion. Pyne had to make clear that the flasher was an unintentional feature, and that the whole billboard would need to be reprinted. Elsewhere, glass pillars for the faith zone languished in Paris, incomplete, and the dark brown paint on the pubic hairs for the body zone had been chipped off in transit.

I asked Ray Winkler, who worked on the Dome’s central show, what the mood was like in those last few weeks. “Oh you know,” he replied. “Mild panic? Sheer panic?”

“I think I probably had a breakdown,” said Pyne.

On 1 January 2000, when the Dome finally threw open its doors to the public, what did the people involved think of what they saw? Some remember enjoying the exhibition, but Michael Heseltine paused before choosing his words: “I think that … we could have done a better job.” Chris Smith told me that the content was “worthy”. Simon Jenkins, who was on the Millennium Commission, said it was “dull”. Bayley noted that the Dome was, in a sense, quite impressive. He added: “You could spend £750m on a pile of horseshit and it would be impressive, but would it be worth the money?”

Soon reports were emerging that turnout was low. In certain parts of the Dome, though, the problem was too many visitors at once. Queues for the body zone spiralled up to two hours long. “In one sense, we’d overhyped it,” Page admitted of that exhibit. In early February, it was announced that in the previous month, the Dome had welcomed less than half the number of visitors required to break even. Page was asked to resign, something that few people I spoke to think was fair. “I’ve never seen anybody so dedicated in my life,” Mike Davies told me, “and I’m prepared to say in public that I think she was the scapegoat.”

By aiming for 12 million visitors, the company behind the Dome created the impossible criteria by which its success would be judged. The combined number of tickets sold for Alton Towers, Madame Tussauds and the London Eye in 2000 was 8m. As the actual number of visitors began to look more like half their projection, the Dome team were forced back to the Millennium Commission to ask for emergency funding three separate times over the course of the year.

After Page’s resignation, the man hired to rescue the Dome was PY Gerbeau, an infectiously optimistic ex-Eurodisney executive who wore suits slightly too big for him and rode around the Dome on a micro-scooter. Newspapers nicknamed him “the Gerbil”. “I do not think,” Falconer began to laugh, “and this is our fault, not his, that he quite had an understanding of the scale of the problem.” Gerbeau seemed to have grasped it by the time he left in 2001, at least, when he told the New Yorker magazine that the 12 million visitors estimation “was one of the two or three stupidest things I have ever heard”.

Gerbeau’s main job was damage limitation. He reduced ticket prices, and brought in a funfair around the edge of the Dome in the summer, and a skating rink in the winter. In the face of adversity, the marketing team for the Dome gamely attempted to turn the ever-worsening reputation to its advantage. Adverts ran of disappointed children asking their parents why they never went to the Dome, with a voiceover saying “The Millennium Experience at the Dome is closing for ever. Maybe you’ll love it – maybe you won’t. Why not come and decide for yourself, while you still can?”

One set of visitors the Dome company could have done without was a gang of would-be thieves who drove a JCB digger into the side of the Dome one day in November, in a failed attempt to steal the Millennium Star, a large gemstone that the diamond company De Beers had contributed to the money zone. Adam Liversage, a press officer at the Dome, was asked about it by a journalist a few weeks later. “In any other press office, something like that would be the story of a lifetime,” he replied. “But here it was just a question of, OK, I’ll go and take a look.” Shortly afterwards, JCB ran an advert featuring a picture of one of their diggers with the tag line “the only thing that worked to plan”.

The Dome closed, with relatively little fanfare, at 6pm on 31 December 2000. Blair had appeared on BBC One’s Breakfast with Frost a few months earlier, and admitted: “If I had known then what I know now about governments trying to run a visitor attraction – it was too ambitious.” At the end of Nicolson’s book, he describes the organisers, under constant attack and fighting an uphill battle to deliver the project, as “throwing a dance on Omaha beach”. “It’s an expression I’ve never forgotten,” Page said.

In February 2001, a public auction for the Dome’s contents was held at the site. One of the most eye-catching lots, a six-foot plastic hamster, went for £3,700 to a man named Brent Pollard, to furnish a visitor attraction he ran in Kent. These days, Millie – short for millennium, as the local Kent schoolchildren named her – resides in a warehouse near the town of Sandwich, along with a large collection of military vehicles owned by Rex Cadman, a friend of Pollard’s who accompanied him to the auction.

“She’s just lovely,” Cadman said proudly, as we stood in front of the slightly chipped fibre-glass figure a few weeks ago. The warehouse also contains a number of other Dome items that Cadman picked up at the auction, including a large oil painting of Blackadder, who featured in a specially commissioned film shown at the Dome. Having spent several months researching how these objects came into existence, I felt strangely humbled by seeing them preserved there, as if I was in the presence of artefacts from some once mighty civilisation. An alien, presented with only these objects as evidence, would have to assume that the civilisation that produced them was naively optimistic, concerned primarily with jolly novelties and with no coherent sense of style whatsoever.

Perhaps the most recognisable element of the Millennium Experience, the outer shell of the body zone, was too big to be sold in its entirety, although tiles from its surface were used as the bidding paddles at the auction. In the end, the body was eventually dumped in a hole near the Dome as landfill. Higgins told me that the feeling was “just get it done, and then line up the skips”.

The Dome lay empty, a ruin before its time, for 18 months while the government struggled to find it a future. Proposals for the building’s afterlife included a super casino, a business park and a stadium for Charlton Athletic. In May 2001, on the morning of Labour’s manifesto launch, the leader of the Conservative party, William Hague, stood outside the Dome to deliver a short speech. This “Teflon tent,” he said, “is the ultimate monument to Labour, and today they both stand empty.”

It wasn’t until a year later, in May 2002, that the US entertainment company AEG stepped in to purchase the building. The deal was that AEG would invest hundreds of millions of pounds into redeveloping the site as a music venue, later to be named the O2 Arena, and give the government 15% of its profits. The site itself was sold for £1.

“I guess they didn’t really have any other alternative,” Alex Hill, the present head of AEG Europe told me as he showed me around the O2 late last year, “but I think the vast majority of people did not believe that something would be created of this level of success.” The O2 Arena opened its doors in 2007, and has been the most popular music venue in the world every year since.

Mike Davies’s versatile building adapted well to its new purposes. Apart from the 20,000-seat live music and sports venue, the Dome now houses an outlet shopping centre, an indoor trampoline park and a bowling alley. There is also a pop-up football experience where you can play against a virtual goalie, just as you could in Higgins’ play zone 20 years earlier.

The success of the O2 is the most obvious vestige of the Millennium Experience, and the one that people involved in the Dome are most keen to emphasise. It’s “a brilliant success”, Mandelson told me a number of times during our conversation. “I’m not going to look you in the eye and say that this is what we always intended,” said Heseltine, “but we’ve taken a lot of stick and, well, I’m going to take a bit of credit.”

It was undoubtedly an expensive way of doing it, but the Dome did give some badly needed new life to the Greenwich peninsula. By 1998, Greenwich had one of the highest levels of unemployment in the country. Regeneration was one of the Millennium Commission’s key considerations when choosing the site. When I mentioned this to Heseltine, he suddenly lit up. “I was absolutely clear that we needed to use this as a regenerative process,” he said. “I have no apologies for that.”

On the December afternoon when I visited, as part of an Up at the O2 tour, I climbed on to the roof of Dome, just as the sun was setting. From the apex of the Dome’s curve, the entire peninsula is visible, a landscape that has transformed during the past two decades. When the construction workers building the Dome looked out from this point in the late 90s, they would have had an uninterrupted view of the Thames looping around them. Today, that great sweeping view is partially obscured by an Intercontinental hotel, several new blocks of flats and Ravensbourne University, which relocated to Greenwich peninsula in 2010.

Before the Dome was built, the peninsula was empty of buildings and covered with toxic soil from the gasworks that had closed back in 1976. Today, the land has been detoxified and the Dome continues to create jobs for local people. But the “regeneration” is still far from perfect. Unemployment rates remain relatively high, and although more affordable housing was built in Greenwich between 2012 and 2016 than in any other London borough, the figure was still only 40%, even as new developers throw up luxury apartment blocks. A Chinese company called Knight Dragon has secured planning permission for 15,000 more homes on the peninsula, and a “design district” of artists’ studios and shops.

There have been other, less visible legacies. Matt Costain, who played the lead role of Sky Boy in the Dome’s central show, told me that the performers’ training programme created an entire industry of circus and acrobatics in the UK. “I meet ‘domies’ all the time,” he told me. “Some of those people are now Cirque du Soleil’s top troubleshooting clowns.” Many of the performers who trained at the Dome went on to perform in that much more successful act of nation branding, the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony.

Like the Olympics, the Dome has left a firm imprint in the national imagination. It is remembered as a white elephant, a cautionary tale. But the truth is that this doesn’t match up with the visitor response at the time. Independent visitor approval polls carried out by Mori showed as many as 90% of the 6 million people who visited the Dome enjoyed themselves. “The thing wasn’t built for architects, it was built for the public,” said Mandelson. “It was for families.”

Children in particular loved the Dome, as the people who were in charge are quick to affirm. Lord Falconer told me he went a staggering 57 times with his family, a fact I confirmed with his daughter Rose, who was nine-turning-10 in 2000. “It’s funny,” she told me, “because we did go about 50 times, and we loved it, but when I think about the Dome even I think of it as a complete disaster.”

For this piece, I spoke to people from all over the country who remember going as children. Some didn’t enjoy themselves, of course. Many remember being frightened of the body zone’s beating heart. But most remembered visiting the Dome as a vivid, strange and invigorating occasion. They told me about the thrill of going to London, of seeing a digital camera for the first time, of feeling part of something bigger than themselves, of excitement about the future they were stepping into, and of dreaming about the Dome even now. One person who visited from south Wales aged 12 told me that she remembers not understanding at the time why the papers were calling it a failure. “I was blissfully unaware of the politics behind it,” she said. “I had a great time.”

The Dome’s less than glorious reputation is a source of regret for some. “One of the things that makes me crossest, when I admit to being cross,” Page confessed, “is that so many people who worked on the Dome, who were so good, have not been allowed to feel good about themselves.” Falconer feels the same. “It was the failure of the politician,” he said, pointing to himself, “not the failure of the people working in the Dome.” It is, however, difficult to know how it could have gone differently. Page told me that, in her view, much of the negative press was to do with the influence of politics on the Dome. “But on the other hand,” she said, “Without the politics, it would never have happened.”

The creators of the Dome set out to provide an experience that would unite the country. In a way, they succeeded. There is something unifying, and typically British, in our collective enthusiasm for enshrining the memory of the Dome as being a bit shit, be that memory accurate or not. It may well be that this same sort of national unity in disdain will repeat itself in the near future. In 2018, Theresa May announced plans for a £120m “Festival of Brexit Britain”, now renamed Festival 2022, showcasing “the best of the UK’s talent in business, technology, arts and sport”. Planning is going ahead, and the festival’s head, Martin Green, expects to announce a programme by the end of 2021. “Oh for God’s sake,” said Heseltine, rolling his eyes when I mentioned the festival. “Put it in Dover and everyone can go before they leave.”