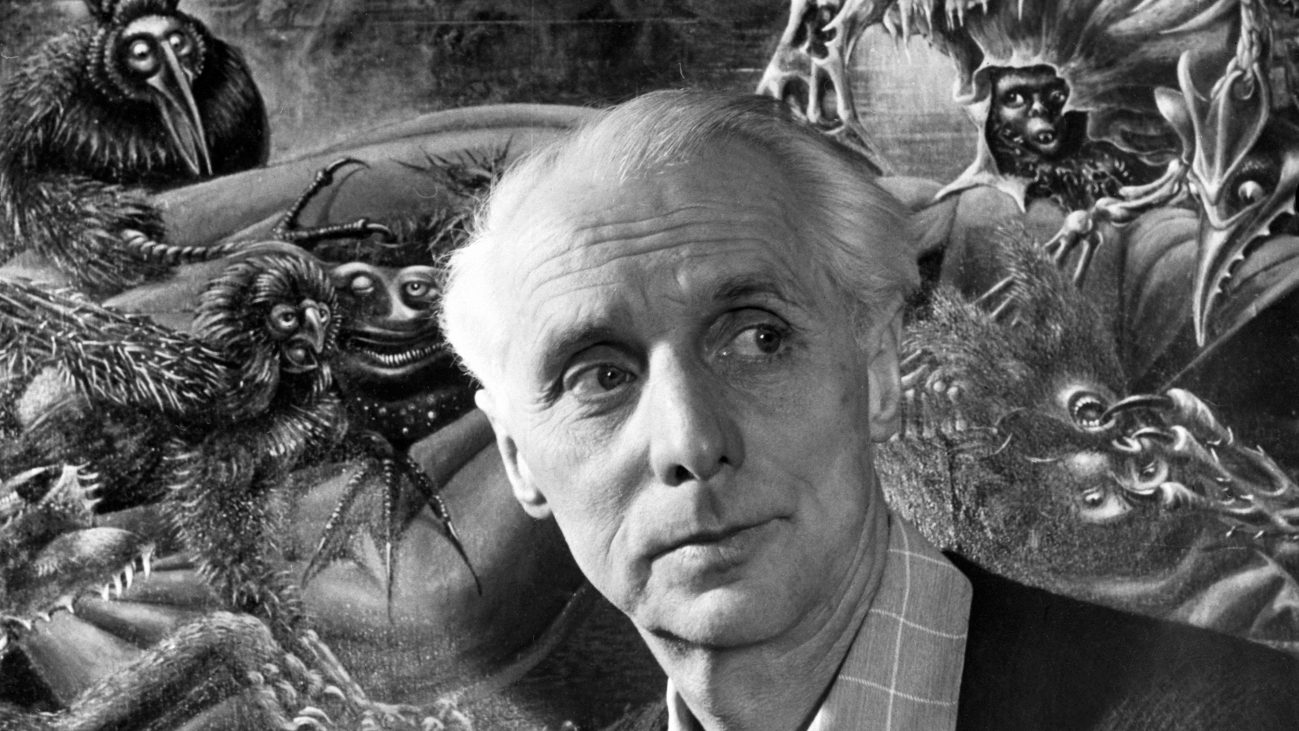

Of all the artworks created during the second world war, few are as unsettling as Max Ernst’s Europe After the Rain II. Painted between 1940 and 1942, it shows a landscape ravaged by war, jagged fragments of buildings left standing among the rubble and two forlorn figures glimpsed among the ruins.

Closer inspection of the work reveals that the shattered vista is actually organic in nature. The broken structures comprise vines and roots, grotesque and deformed giant plants, animal carcasses and bones; a study in putrefaction as much as destruction given an extra surreal twist by the pair of figures. One is a woman dressed in green facing away from the viewer, the other has the body of a classical warrior and the head of a bird carrying a battle standard with a couple of small, frayed banners.

Melancholy and nightmarish, Europe After the Rain II hints at the darkness and destruction lurking just beneath the thin veneer of civilisation, as eloquent a depiction of historical evil as Picasso’s Guernica. It was also prescient, painted in the early years of a war that would leave much of Europe in ruins the way Ernst’s The Petrified City, painted in 1933 as Hitler came to power and The Angel of Earth, a 1937 work depicting a monster raging across a landscape, seemed to anticipate coming events.

Europe After the Rain II is also an intensely personal work, painted during the most frightening and uncertain period of the artist’s own life.

By 1938, Ernst had been living in Paris for more than a decade, during which he had been a founding father of dadaism and a key figure in the development of surrealism. That year a growing distaste for being associated with groups and movements led to him heading south to an old vintner’s residence in the village of Saint-Martin-d’Ardèche where he set up home with his then-partner and fellow artist Leonora Carrington.

When war broke out the following year, however, German-born Ernst was interned as an enemy alien until released after a campaign by influential friends. On making his way home he found that a traumatised Carrington had sold the house to a local innkeeper for a bottle of brandy and fled.

Soon afterwards the Germans invaded France, and Ernst was arrested by the Gestapo – two of his works had appeared in the Nazi degenerate art exhibition – and placed in a camp near Marseille from which he managed to escape.

Encouraged by Peggy Guggenheim, the American heiress and art patron whom he had met a few years earlier, Ernst realised his best chance lay in making his way to Spain and attempting to reach the US from there.

In July 1941 he took a train south, where, just before the border, a check by French police revealed issues with Ernst’s papers. “I am afraid it is my duty to have you transferred to an internment camp for processing,” said the officer. “You will take your luggage and make your way to the train over there on the left.”

The man looked a crestfallen Ernst right in the eye. “Under no circumstances,” he said, “confuse it with the train standing at the other platform, which we have just checked and which is about to depart across the border without stopping.”

He made his way to Lisbon and boarded a flying boat to New York. Arriving at almost the same time was the unfinished canvas of Europe After the Rain II that he’d been forced to relinquish during his flight from France. He had scribbled “Max Ernst, c/o Museum of Modern Art, New York” on the packaging and hoped for the best.

It was hard to begrudge Ernst these strokes of fortune as he had already experienced his fair share of conflict having served in the German artillery for the entire duration of the first world war on both the western and eastern fronts, being wounded twice and bearing a heavy psychological burden.

“On the first of August 1914, ME died,” he wrote in his autobiography. “He was resurrected on 11th November 1918 as a young man aspiring to find the myths of his time.”

These aspirations would place the artist at the forefront of the revolutionary cultural developments that flourished after the conflict.

His father Philippe was a teacher at a school for deaf children and an amateur artist. Ernst said it was when he watched his father pull up a tree to improve the landscape he was painting that he promised himself never to be so shackled to realism. Philippe would also take his children on long walks deep into the dense forest close to their home in Brühl, near Cologne, which strongly influenced Ernst’s future work.

Ernst took a combined degree in art history, literature, philosophy, psychology and psychiatry at the University of Bonn and was particularly fascinated by the paintings produced by patients at the city’s psychiatric hospital, which inspired him to begin painting himself. While he didn’t graduate, claiming later that he avoided “any studies that might degenerate into breadwinning”, in Bonn he met Apollinaire, developed a deep friendship with Hans Arp and began to form the artistic style that would make him such a key figure in modern art.

In 1919, Ernst visited Paul Klee in Munich, studied paintings by Giorgio de Chirico and founded the Cologne Dada group. He also developed an innovative collage method, taking images from catalogues and brochures and subverting their intentions in frequently witty fashion. He devised the frottage technique, making rubbings from wood and other textured material, influenced by childhood nightmares of faces and figures emerging from the grain of his bedroom cupboards, and grattage, a similar method that scraped paint across canvas to reveal objects placed beneath.

Both methods were attempts to create art free of the influence of memory or experience, especially with the trauma of the war still so fresh. A move to Paris in 1922 put Ernst at the heart of the avant-garde and when André Breton published his Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, Ernst recognised in it a path to “psychological automatism”, work untainted by the past and unscarred by trauma.

Ernst’s arrival in America felt like an important reset and he met with great commercial success there, making him financially secure for the first time in his life. He was briefly married to Guggenheim, then spent the immediate postwar years in Arizona with his new wife, American artist Dorothea Tanning.

A return to France with Tanning in 1953 signalled a final act in his life where finally he was happy and settled and lived life as that rare thing, an artist who found success during his lifetime in Germany, France and the USA and ensured a legacy that would long outlive him.

Which might have come as a surprise. Asked in 1959 about what hope he had for the legacy of his work he replied: “Rebellious, heterogeneous, full of contradiction, it is unacceptable to specialists of art, culture, morality. But it does have the ability to enchant my accomplices: poets, pataphysicians and a few illiterates’’.