Margaret Harris reviews The Basis of Everything: Rutherford, Oliphant and the Coming of the Atomic Bomb by Andrew Ramsey

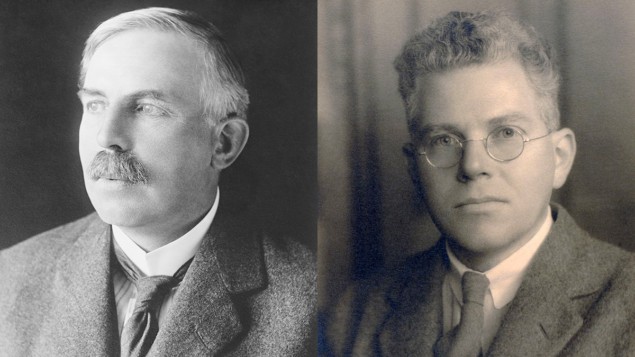

Eighty-five years after his death, and more than a century after the discoveries that made him famous, Ernest Rutherford’s reputation as one of history’s greatest experimental physicists is undiminished. His scientific achievements – the studies of radioactivity that earned him the 1908 Nobel Prize for Chemistry; the discovery of the atomic nucleus the following year; and the observation of the first artificial nuclear reaction in 1917 – stand out even in an era that produced many notable physicists.

Rutherford was a larger-than-life character, given to bellowing the hymn “Onward Christian Soldiers” as he strode through the lab, and possessed of a prodigious talent for swearing at recalcitrant equipment. He has, accordingly, been well-served by biographers: a volume dedicated to his life and letters came out shortly after his death in 1937, and numerous other studies have been published since.

Mark Oliphant also has a place in physics history. As Rutherford’s student-turned-colleague at the University of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory, Oliphant had a hand in the discovery of tritium, a heavy isotope of hydrogen that proved vital to the later development of nuclear weapons. As head of the physics department at the University of Birmingham during the Second World War, he led a high-priority programme to improve radar systems, giving Britain’s defenders a crucial edge over their Nazi foes.

Also, like many physicists of his generation, Oliphant was involved in the Manhattan Project that built the first atomic weapons. Initially he was a go-between, conveying scientific information from bombed-out Britain to the US. Later, he was second-in-command to Ernest Lawrence, whose cyclotrons helped separate fissionable uranium-235 from the more plentiful uranium-238.

Yet as important as these accomplishments are, there is an air of “always the deputy, never the sheriff” about Oliphant’s career. This makes him an unusual choice to counterbalance Rutherford in Andrew Ramsey’s The Basis of Everything: Rutherford, Oliphant and the Coming of the Atomic Bomb. The pairing is also surprising given that Rutherford died just as Oliphant was starting to make an independent name for himself. The senior physicist is therefore absent in the final, necessarily Oliphant-focused, third of the book, which gives it a rather anticlimactic feel.

Moreover, while Ramsey argues convincingly that Rutherford and Oliphant were unusually close, more like father and son than mentor and student, Oliphant was neither the only nor even the most talented young scientist to fall under the sway of the charismatic and gregarious Rutherford. As Ramsey points out, a dozen of Rutherford’s students, from Frederick Soddy in 1921 to Peter Kapitza in 1978, went on to win Nobel prizes. Why not write about one of them?

The answer – a good one – lies in the pair’s shared experiences growing up. Ramsey describes their respective upbringings in parallel in the book’s early chapters before switching to a conventional chronological structure. Rutherford, a New Zealander, was raised in a series of ramshackle frontier towns where his semi-literate father eked out a living in the flax trade. Thirty years later, the Australia-born Oliphant was little better off.

Both struggled mightily to obtain (and pay for) the kind of education that would enable them to make a living as a scientist. Neither slotted easily into the semi-aristocratic and deeply Eurocentric “club” of late 19th and early 20th-century physics. And Oliphant, especially, learned the hard way that winning a coveted 1851 Research Fellowship (the same prize that took Rutherford to the Cavendish a generation before) was no guarantee of financial stability – particularly since he, unlike Rutherford, brought his wife, Rosa, with him to Cambridge.

While The Basis of Everything deals competently with the technical aspects of its subjects’ careers, Ramsey – a journalist for Cricket Australia – is not a science specialist. Readers new to nuclear physics or the history of the atomic bomb would be better served by the science-focused accounts in the book’s bibliography. Ramsey does, however, have a good feel for the practicalities of research and a journalist’s eye for details.

One theme that comes across most vividly – and, for this reader, enjoyably – is the frankly dangerous nature of experimental physics during the 1920s and 1930s. Early nuclear physicists from the Curies onwards were famously (and sometimes fatally) indifferent to the hazards of working with radioactive materials. However, as Ramsey shows, lax radiation safety wasn’t the half of it. While in Australia, Oliphant devoted considerable time to purifying samples of mercury, spending “hours boiling and distilling the metal while its toxic vapour rolled down the stairs and seeped into the university’s basement workroom”. At the Cavendish, he was once knocked unconscious by a 20 kV shock that melted the soles of his shoes to the laboratory floor. The fact that Oliphant lived to be an old man, dying in 2000 at the age of 99, is little short of astonishing.

A further welcome strength of the book is its focus on the mundane hardships of academic life. In 1927 Oliphant’s fellowship at the Cavendish was worth just £250 a year, or about £12,000 in today’s money. Worse, Rutherford was incredibly tight-fisted when it came to laboratory funds, and his students regularly had to pay for their own equipment and consumables to make up the shortfall. In Oliphant’s case, this meant shelling out nearly 10% of his annual salary on a mercury diffusion pump vital to his research – a sum he and Rosa could ill afford.

Another of the Cavendish’s star students, James Chadwick, attributed Rutherford’s extreme parsimony to modesty: the bluff old Kiwi simply could not believe his ideas and work were worth spending money on. Whatever the cause, though, Rutherford’s penny-pinching ways were desperately hard on Oliphant. After paying £80 in college fees, £20 for textbooks and £2 per week for a flat consisting of a bedroom, living area and combined kitchen-bathroom, he and Rosa (who lacked qualifications that would have allowed her to get a paying job) could barely afford to eat, never mind keep warm.

In this respect, The Basis of Everything, which was first published in Australia in 2019 but only released in the UK this year, feels uncomfortably timely. Lab safety has improved since Oliphant left the Cavendish in 1936, but as the UK heads into an energy crisis, some readers may find unwelcome parallels with other aspects of the experiences described in this engrossing and well-observed book.

- 2022 HarperCollins £20.00 384pp