With up to 40 per cent of carbon emissions coming from the construction industry, the profession needs to find ways of adapting the type of buildings it designs, and fast. The default option for any project should be to adapt and re-use an existing building, one of the key demands of the AJ’s RetroFirst campaign.

Our ongoing series seeks to celebrate the projects that save buildings from ruin or give them a brand new life.

Today we hear from Hana Loftus of HAT Projects about her practice’s recently approved plans to return Lowestoft’s empty and decaying former town hall to a civic role as a registry office, venue for civil ceremonies and a new home for Lowestoft Town Council.

Advertisement

Source:HAT Projects

Hana Loftus, director of HAT Projects

Tell us about the scheme

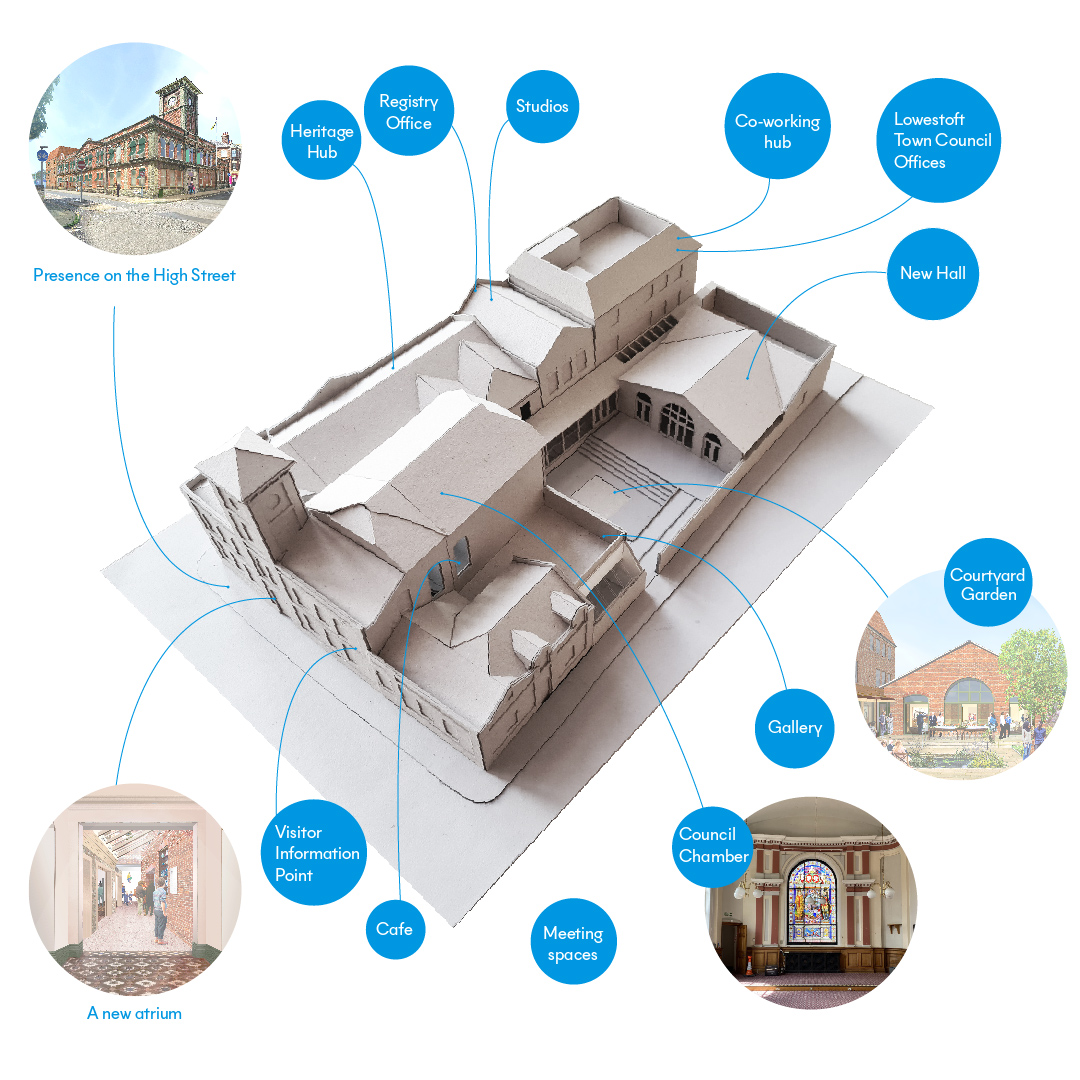

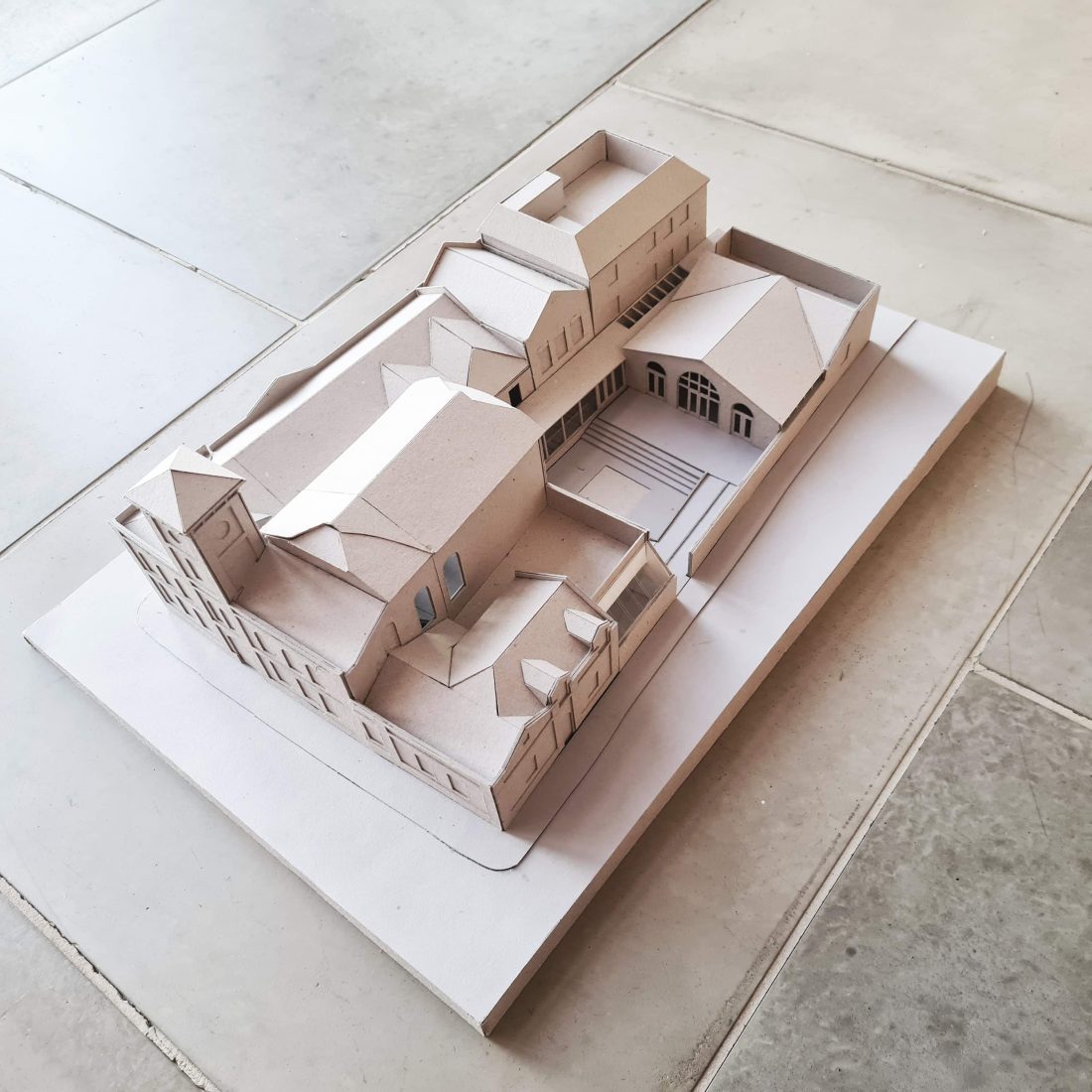

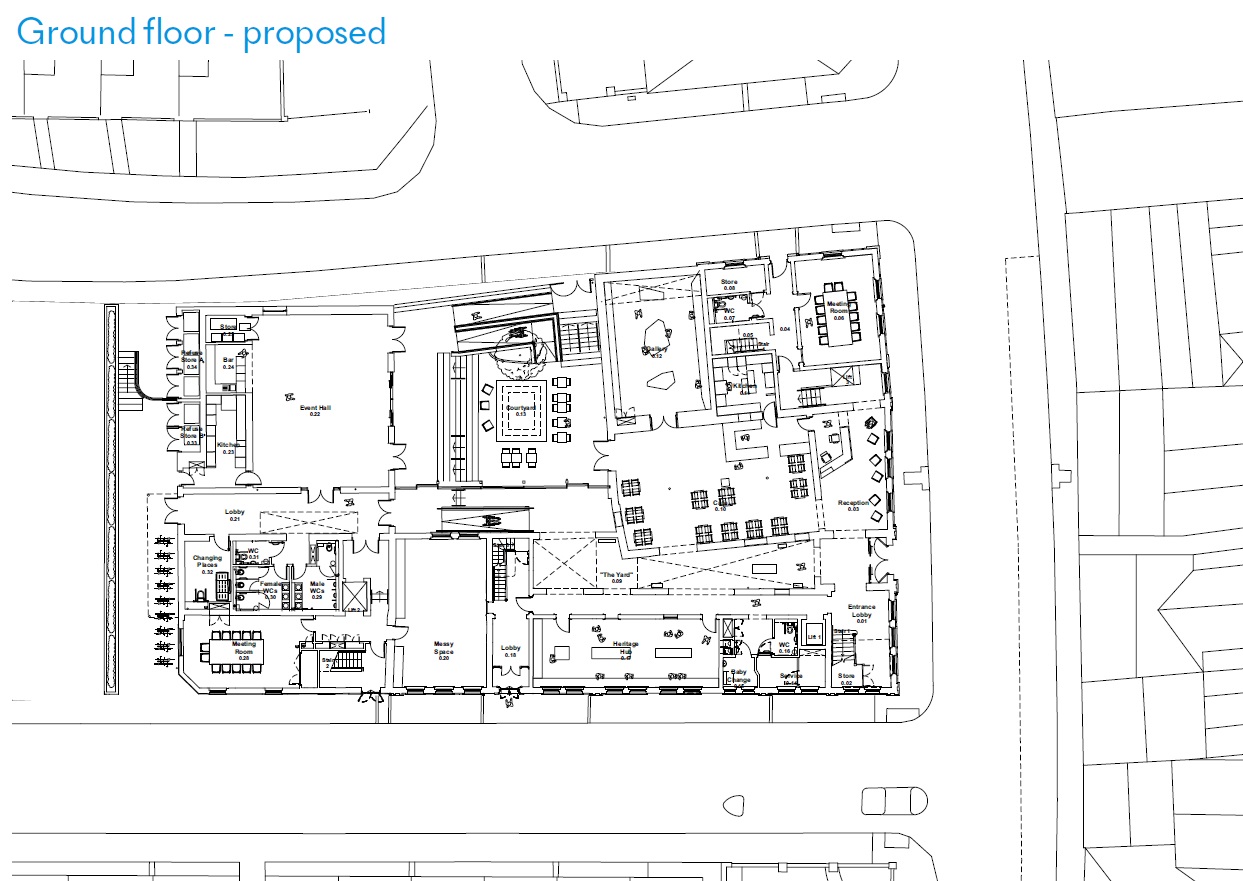

The project is the complete restoration of the Grade-II listed town hall in Lowestoft, extending it to complete the urban block on which it sits.

The construction value is approximately £6.7 million and it will be starting on site in 2024, having received planning and listed building consent, and grant funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund as well as other local and national funders this year.

What were the challenges of the existing building?

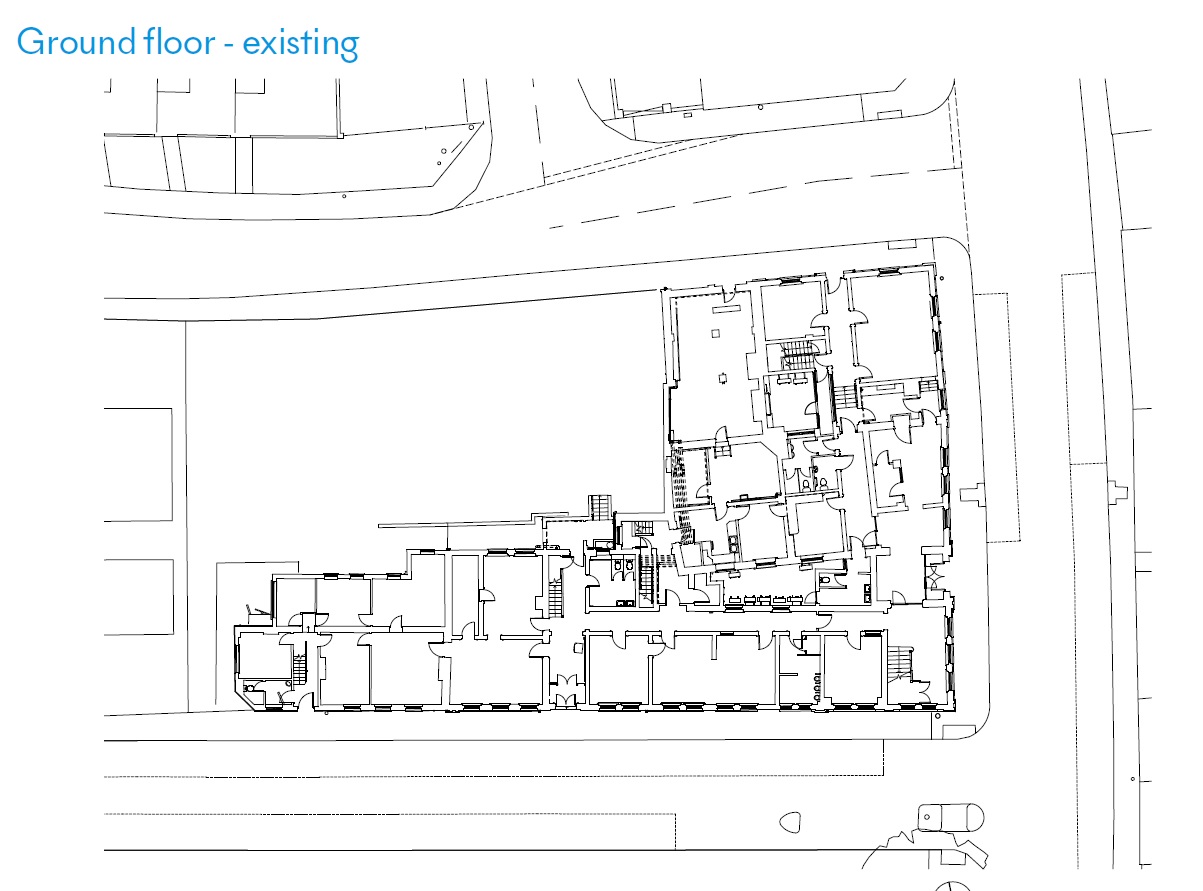

The building is an important civic landmark in Lowestoft but has been unused since 2017. It has deteriorated substantially since then, and there was quite limited information about its condition, services and so forth. Therefore the team have had to do a lot of investigation work to uncover the extent of the degradation, prevent further decay, and understand the construction of the building.

There is dry rot, so we are having to look at substantial replacement of floor joists in some areas as well as measures to ensure this does not recur.

In extending the building, we looked carefully at the historic urban pattern of the area, which suffered demolition post-war, leaving the town hall, and an adjoining 1830s pub linked to it in the mid-20th century, alone on what was once a very dense urban block.

Advertisement

The former pub has different floor levels to the main building, and a rather different architectural language – much plainer and much adapted rather than the set-piece Italianate town hall itself.

We are restoring the block form, building right up to the pavement line with the new extensions, while introducing a courtyard in the centre to bring light in and create sheltered, peaceful outdoor space. We want to create the sense of an agglomeration of buildings making up a single block, dating from different periods, that work together without being uniform.

Inside, we are opening up a neglected internal lightwell and glazing it over to create a new spine to the building – a move that unlocks the circulation. We are using the ground floor ‘undercroft’ below the set-piece council chamber to create a new café which will have a lot of found surfaces, quite rough, but speaking of the history of the building.

The biggest technical challenge for historic buildings is plant and services

Without doubt, the biggest technical challenge for retrofitting historic buildings, particularly in dense urban settings, is accommodating plant and services. Air-source heat pumps (ASHP) cannot be placed in basements, unlike traditional boilers, as they need air (obviously). They also must be visually and acoustically screened.

With the units required for a building of this size being very large, this was a real challenge, and alongside this, we needed to incorporate a lot of ventilation plant and extract for the scheme’s two catering kitchens. Developing architectural solutions that could accommodate all this without any visual impact from the street was a challenge, so the new extensions, and an upwards extension of the former pub wing, all incorporate hidden roof plant areas, concealed visually and acoustically behind parapets and elements of the massing.

Overheating to the building generally is an issue, with most of the historic rooms being south-facing and single aspect, and one we wanted to resolve passively with no active cooling.

We want to upgrade airtightness and thermal performance of windows, but this needs to be done using secondary glazing rather than double glazing, because the historic windows contain etched glass that is an important heritage feature. As a result, natural ventilation is not feasible so we are installing external awnings to all the south- and west-facing windows (apart from those in the council chamber, which are too big and have stained glass) along with MHVR.

This is actually in line with the historic record, as we found evidence in historic photos that those windows originally had awnings, albeit of a slightly different kind.

Source:HAT Projects

Had demolition or partial demolition ever been considered?

We are only demolishing small non-original extensions to the building. More extensive demolition was not an option given the listed status of the town hall, but we would have resisted it anyway.

We try to alter as little as possible

We looked at complete demolition of the pub building but it did not make sense either in terms of cost or design. Internally, we are keeping as much as possible of the existing floor plan and only the pub building is being completely remodelled. For us, when we work with existing buildings, there is a process of trying to match the elements of the brief with the spaces that already exist within the building – finding the right space for the right function.

We don’t start from the position of erasing the internal floor plan and we try to alter as little as possible while clarifying circulation and making the building legible for its users.

Aside from retaining the original fabric, what other aspects of your design reduce the whole-life carbon impact of the building?

We always look at carbon across all aspects of design and operation. Operational carbon for this project will still be significant – there is limited fabric performance upgrading that can be done – so ensuring sensible zoning of functions, user-friendly controls and low-maintenance and management costs are important. The client is also keen to have PVs so we have designed and gained planning consent for panels on all south, west and east-facing roofs.

We've more concrete in the building than we'd like due to the groundworks

We always consider the embodied carbon of materials as we work on the design and specification, and are careful to choose structural systems and finishes that balance longevity with low embodied carbon.

Having said that, not all materials we are using on this project are low-carbon. We have more concrete in the building than we would like, but this is due to the groundworks and the levels around the site, which require retaining structures. And the new extensions will be clad in brick, as well as having some structural brick elements. But for this project, that is the right solution.

The town hall – and the wider context – has a strong brick character and this is a seafront town where robustness and longevity are important and require sturdy external materials. The town hall has lasted over 100 years and, while we are having to do a comprehensive restoration, the shell and structure is basically sound. We would like our extensions to be similarly robust and long-lasting, so while using brick is a higher-carbon option, it is the right one for this project and this site.

Were the planners supportive of the proposals?

Yes, we were very glad to have had a positive dialogue with the planners from the start and very little negotiation was required on any aspect of the project.

They were supportive and understanding of the design moves required to make the building work for the 21st century, including awnings, ventilation, the ASHPs and PVs. It is a pleasure to be able to say we had a smooth process through planning, and due credit to East Suffolk Council on this one.

Source:HAT Projects

There's no point in trying to wish away fundamentally very big boxes

What have been the main lessons from the project that you could apply to other developments?

It is important to explain to clients how building design has changed now with low-carbon heating systems and ASHPs. The space and massing implications are significant and this must be an early conversation across the design team and with the planners.

There is no point in trying to wish away what are fundamentally very big boxes; they need to be considered as part of the design and massing from the start.

Is your approach to retrofit and the way you talk about it with clients changing?

We've always worked on a lot of existing buildings, and have sought to work with the way they were originally designed rather than fighting the building.

We place more emphasis now on issues like overheating at an early stage, and explaining to clients that it isn’t just about improving fabric performance and installing low and zero-carbon (LZC) technologies; they will also need to consider how their operational and behavioural habits can change to use less energy in use.

For example, we spent a good deal of time explaining how behaviours could avoid the need for active cooling, but this would require the building occupants to understand and commit to doing things a bit differently – from dressing for the weather to ensuring that night-time purge ventilation is activated, and of course using the external awnings to avoid heat gains building up.

Source:HAT Projects

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

Leave a comment

or a new account to join the discussion.