|

SUBPHYLUM TAPHRINOMYCOTINA = CLASS ARCHIASCOMYCETES

This is the group that Nishida and Sugiyama (1994) called the class Archaeascomycetes. I have raised it to subphylum level according to the system of Ericksson (2000) who claims that they are the sisters to all of the other Ascomycota, and they appear to be the groups from which the other Ascomycotes arose. However, the following classes differ from each other structurally and, according to Ericksson (2000), on the basis of their SSU rRNA sequences. Thus, the diversity of the group of four classes really indicates that they are defined by exclusion from the well-defined and natural groupings: Saccharomycotina and Pezizomycotina. Also, I am troubled by their apparent primitiveness. All of these taxa (except the fission yeasts) are parasites and, therefore, may only appear to be primitive through reduction. Clearly, the book is not closed on the taxonomy of the Ascomycota.

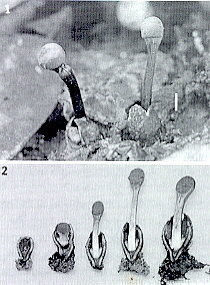

CLASS NEOLECTOMYCETES

These are fungi that produce large fruiting bodies (ascocarps up to 9 cm tall). The ascogenous hyphae do not have crosiers. The asci open by a slit. The ascospores germinate to form yeast-like conidia. The mycelia and fruiting bodies are associated with spruce roots and may be parasitic.

ORDER NEOLECTIALES

Neolecta

CLASS PNEUMOCYSTIDOMYCETES

These live as parasites in the alveoli of certain vertebrates and, therefore, are of significant medical importance. They grow as yeasts that divide by fission (not budding). They fuse to form asci of 8 banana-shaped ascospores.

ORDER PNEUMOCYSTIALES

Pneumocystis

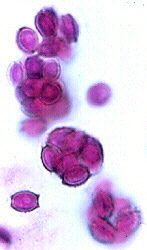

CLASS SCHIZOSACCHAROMYCETES = OCTOSPOROMYCES

These are the fission yeasts. They fuse to form asci of four or eight ascospores. They live as saprobes in fruit juice.

ORDER SCHIZOSACCHARIALES

Schizosaccharomyces

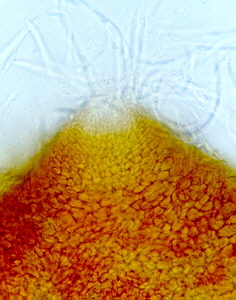

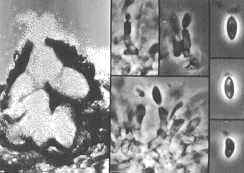

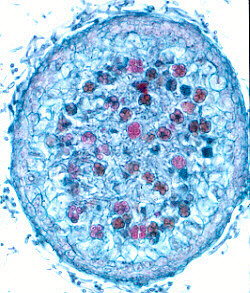

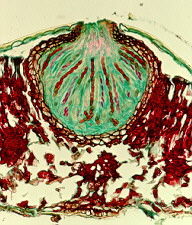

CLASS TAPHRINOMYCETES

Biotrophic parasites of seed plants and ferns causing galls, leaf curls, deformed fruits and witches brooms. Intercellular or subcuticular dikaryophase mycelium in parasitic phase with terminal chlamydospores or ascogenous cells, each forming a single ascus in a hymenium-like layer; after nuclear fusion and mitosis, ascogenous cells often divide to give a basal stalk cell with ascus at the apex; ascospores may bud within ascus so that it appears multispored; saprotrophic phase of budding monokaryotic cells; can be cultured in the yeast state.

ORDER TAPHRINALES)

Taphrina, Protomycetes.

SUBPHYLUM SACCHAROMYCOTINA = HEMIASCOMYCETES

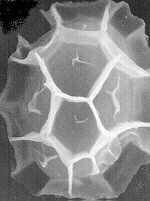

These are the budding yeasts. Vegetative phase unicellular yeast-like or filamentous; asci one-walled, naked, not borne on ascogenous hyphae, produced singly, following karyogamy; no ascocarps.

CLASS SACCHAROMYCETES

ORDER SACCHAROMYCETALES = ENDOMYCETALES

Saccharomyces, Dipoascus.

SUBPHYLUM PEZIZOMYCOTINA

These comprise most of the ascomycota. The organisms form mycelia that make ascocarps (ascus-bearing structures also called ascomata) with hymenia. Some of the taxa are lichenized (enter into a symbiotic relationship with algae to form lichens). Some of the taxa have lost the ability to undergo meiosis and, although they might fuse, they can not produce ascospores or asci. Such taxa were once called the Fungi Imperfecti or Deuteromycota. Such a distinction is decidedly artificial. On the other hand, symbiotic entities like lichens do not easily fit into a natural system unless the fungal symbiont (mycobiont) is given complete preference. To be consistent with current fungal taxonomic systems, I will include the lichenized fungi in this system and describe the lichens in a separate page. This subphylum follows that of Ericksson (2000), but I have added a 9th class, Laboulbeiomycetes, a group of uncertain status in Ericksson's system.

CLASS ARTHRONIOMYCETES

This class appears to be monophyletic. Most of them are lichenized and produce asci with double walls and slits. The asci elongate to a rostrum when discharging spores. The ascocarps are apothecia with a naked hymenium.

ORDER ARTHRONIALES

Arthonia, Chrysothrix, Melaspilea, Roccella, Arthrophacopsis.

CLASS CHAETOTHYRIOMYCETES

This class appears to be monophyletic. Most species are saprobes on vascular plants, dead wood, lichens, etc. Some are human pathogens. The ascocarps are small perithecia that contains paraphyces.

ORDER CHAETOTHYRIALES

Chaetothyrium, Capronia, Adelococcus, Verrucaria.

CLASS DOTHIDIOMYCETES

Typically, these form bitunicate asci within perithecia (members of the order Patellariales produce apothecia). The asci usually are associated with paraphyses-like structures (pseudothecia). The spores are septate. This class and the Chaetothyriomycetes corresponds to Loculoascomycetes in some earlier systems and is often referred to as "bitunicate ascomycetes". Five orders are recognized in this system (after Ericksson, 2000). Some families will probably have to be transferred to the Chaetothyriomycetes when more molecular data are available.

ORDER CAPNODIALES

Capnodaria, Capnodium, Achaetobotrys, Antennulariella, Coccodinium, Metacapnodium.

ORDER DOTHIDIALES

Asci ovoid, club-shaped or cylindrical, grouped in small locules without pseudoparaphyses in pseudothecia; pseudothecia separate or grouped on or in stroma; ascospores usually uniseptate.

Dothidea, [Mycosphaerella, Guignardia both incertae sedis].

ORDER HYSTERIALES

On dead woody branches and bare wood; with distinct boat-shaped, carbonaceous pseudothecia opening by longitudinal slit and appearing apothecium-like when moist.

Hysterium.

ORDER MYRIANGIALES

Mostly tropical or subtropical, epiphytes, parasites or hyperparasites on fungi or scale insects on living leaves and stems; asci globose, scattered individually throughout ascocarp.

Myrangium, Elsinoe.

ORDER PATELLARIALES

Asci in apothecia.

Patellaria

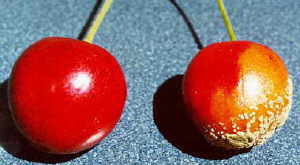

ORDER PLEOSPORALES

Asci long, cylindrical, separated by pseudoparaphyses in relatively large, uniloculate, usually solitary pseudothecia; ascospores commonly phragmosporous or dictyosporous, pigmented.

Venturia, Delitschia, Leptosphaeria, Lophiostoma, Melanomma, Montagnula, Phaeosphaeria, Phaeotrichum, Pleospora, Sporormia, Teichospora.

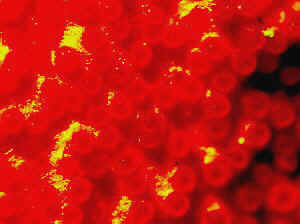

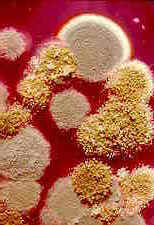

CLASS EUROTIOMYCETES

This class appears to be monophyletic. Two orders are accepted. The Elaphomycetaceae form a monophyletic group with Eurotiales and are not treated as a separate order, but should perhaps be placed in a separate suborder in Eurotiales. Asci are small, evanescent and are produced at different levels within the ascocarp which may vary from a loose weft of hyphae bearing asci to a well organized structure with a definite wall; the ascocarp is often enclosed by a cleistothecium (but osteolate in some); conidia common; widespread and often associated with seeds, soils, and as animal parasites. "The blue and green molds". Some like Aspergillus and Penicillium are form-taxa. That is, sexual structures are not known. The class has 2 orders.

ORDER EUROTIALES

Eurotium, Eupenicillium.

ORDER ONYGENIALES

Gymnoascus, Eremascus, Onygena, Ascosphaera, Arthroderma

CLASS LECANOROMYCETES

This class contains most of the lichenized fungi. Most produce asci in apothecia with a naked hymenium. Asci usually thin-walled with a thicker wall at the distal end. Dehiscence is rostrate. This class is used for most of the discolichens, but it is not strongly supported in phylogenetic analyses. This is a large and diverse class of 5 orders and 500 genera.

ORDER AGYRIALES

Agyrium, Lithographa, Anamylopsora, Elixia.

ORDER GYALECTALES

Coenogonium, Gyalecta.

ORDER LECANORALES

Acarospora, Hymenelia, Anzia, Arctomia, Anthroraphis, Biatorella, Calicium, Calycidium, Catillaria, Cetradonai, Cladonia, Coccocarpia, Collema, Crocynia, Dactylospora, Gypsoplaca, Haematomma, Arctopeltis, Lecanora, Lecidea, Loxospora, Megalaria, Macarea, Miltidea, Micoblastus, Ophioparma, Pachyascus, Pannaria, Parmelia, Physcia, Porpidia, Psora, Ramalinia, Rhizocarpon, Sphaerophorus, Stereocaulon, Lobaria, Nephroma, Peltigera, Placynthium, Fuscidea, Letrouitia, Teloschistes.

ORDER LICHINALES

Gloeoheppia, Heppia, Lichina, Peltula.

ORDER PERTUSARIALES

Megaspora, Pertusaria.

CLASS LEOTIOMYCETES

They have thin-walled asci that are inoperculate. The mildews are part of this class (as indicated by molecular studies). Most produce apothecia (the mildews produce reduced cleistothecia).

ORDER CYTTARIALES

Cyttaria.

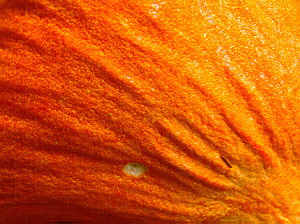

ORDER ERISIPHALES

Biotrophic parasites; ascocarps with 1 to several oval-shaped to club-shaped explosive asci; ascospores unicellular, colorless; chains of conidia arising in basipetal succession from mother cell on superficial colorless mycelium; penetration of host by haustoria confined to epidermal cells. "Powdery mildews."

Erysiphe, Microsphaera, Uncinula.

ORDER HELIOTIALES (HELOTIALES)

Asci inoperculate in distinct hymenium in apothecia of varying form; mostly saprotrophic but with a few plant pathogens.

Monilinia, Bulgaria, Dermea, Geoglossum, Hemiphacidium, Hyaloscypha, Leotia, Loramyces, Phacidium, Rustroemia, Sclerotinia, Vibrissea, Ascocorticium.

ORDER RHYTISMATALES

Ascodichaena, Cryptomyces, Cudonia, Rhytisma.

ORDER THELEBOLALES

Thelebolus.

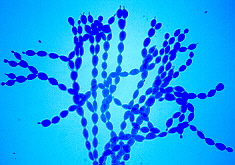

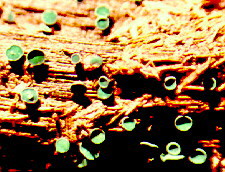

CLASS ORBILIOMYCETES

This class contains dry rot fungi, as well as taxa that feed on other plants. When in the presence of nematodes, some will elaborate capture mechanisms with which they can significantly reduce the populations of soil nematodes. Arthrobotrys is the anamorph (asexual form) of small cup fungi, in the genus Orbilia.

ORDER ORBILIALES

Orbilia, Hyalorbilia

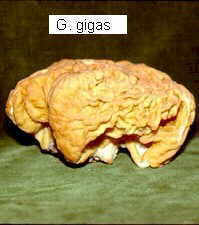

CLASS PEZIZOMYCETES

Thin-walled asci operculate in distinct hymenium. Most produce apothecia of varying shapes, large to minute; saprophytic on soils, dung, wood and plant debris. Others (truffels) produce subterranean (hypogeal) ascocarps that are modified apothecia in which the acsi have become inoperculate. This large class has a single order (PEZIZALES)

ORDER PEZIZALES

Anthracobia, Ascolobus, Ascodesmis, Caloscypha, Carbomyces, Gyromitra, Glaziella, Helvella, Karstenella, Acervus, Pyronema, Sphaerosoma, Peziza, Morchella, Rhizinia, Sarcoscypha, Sarcosoma, Tuber.

CLASS SORDARIOMYCETES

These have unitunicate asci in perithecia. The asci open by a pore This assemblage is supported by SSU rRNA as a natural group. The 8 orders are distributed among 3 subclasses: Hypocreomycetidae, Xylariomycetidae, and Sordariomycetidae. This is a large and diverse class of nearly 800 genera.

ORDER HALOSPHAERIALES

Halosphaeria.

ORDER HYPOCREALES

Perithecial fungi with unitunicate asci; perithecia usually in a well-developed stroma which is usually light-colored; asci are long and cylindrical, with a thickened apex; 8 ascospores which are filiform, hyaline, septate and break apart easily; mainly parasitic on grasses, insects, spiders and other fungi.

Bionectria, Melanospora, Claviceps, Hypocrea,Nectria, Niesslia.

ORDER MICROASCALES

Chadefaudiella, Microascus.

ORDER BOLINIALES

Endoxyla, Catabotrys.

ORDER DIAPORTHALES

Melanoconis, Valsa.

ORDER OPHIOSTOMATALES

Kathistes, Ophiostoma.

ORDER SORDARIALES

Perithecia are ostiolate with persistent, unitunicate asci; asci usually embedded in a stroma which may be composed of both host and fungus tissue or fungus tissue only: ascocarps are usually dark and carbonaceous.

Annulatascus, Batistia, Cephalotheca, Chaetomium, Chaetosphaeria, Coniochaeta, Helminthosphaeria, Lasiosphaeria, Nitschkia, Neurospora, Sordaria.

ORDER XYLARIALES

Amphisphaerella, Clypeosphaerella, Diatrype, Graphostroma, Hyponectria, Xylaria.

CLASS LABOULBENIOMYCETES

Mainly obligate parasites of insects, especially beetles, with distinctive non-mycelial and determinate growth pattern. With main body of the fungus, the receptacle, attached to host by basal cellular holdfast; single, simple haustorium penetrating host; receptacle varies in size and complexity, in some row of 3 cells, in others large number of cells superimposed in tiers. Lateral filamentous appendages and 1 or more sessile or stalked perithecia arise on receptacle; asci usually 4-spored; ascospores usually colorless, elongated and more or less spindle-shaped, 2-celled with large basal cell, each surrounded by a colorless envelope thickened at the lower end; ascus wall deliquesces prior to spore discharge.

ORDER LABOULBENIALES

Laboulbenia. |